Are we helpless about our sulphur emissions?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Sulfur Rules Rolled Back

₹3,000 Cr Solar IPO Explained

Sulfur Rules Rolled Back

To “go green” is to get a million different things right, many of which can feel impossibly hard. Yesterday, we spoke about the economics of air pollution, and the many ways pollution acts as a drag on our economy. Today, we’re talking about the opposite — about how challenging it is to actually address pollution in practice.

The Indian government has spent a long time trying to clean up our legacy sources of energy – especially coal. Only, this proved to be trickier than one would hope. Many of our coal power plants were built decades ago. We had different priorities back then; we were simply looking to electrify India, in a way that made sense given our economic and political constraints. This worked to bring a lot of India on the grid. But now those plants have operated for a few decades, and their commercials have crystallised, cleaning things after the fact has been harder than we hoped.

This reality hit home on July 11, 2025, when the Union Environment Ministry rolled back a key anti-pollution mandate, exempting some coal power plants from cutting their sulfur emissions. But what forced us to rethink our ambitions? Let’s dive in.

The challenge of filtering sulphur

When a lump of coal turns into electricity, it releases a toxic cocktail into the air: sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, mercury, and all sorts of other stuff that’s terrible for you.

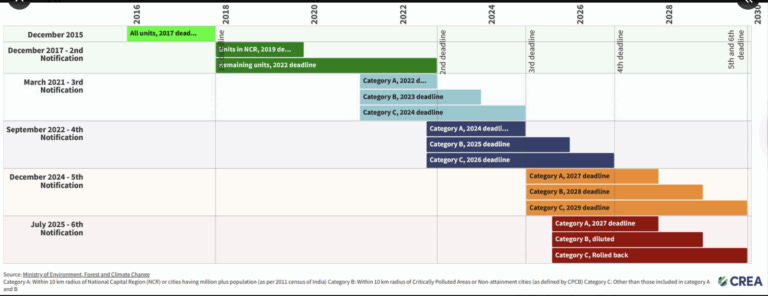

Back in December 2015, worried by the impact coal has on air quality, India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (or “MoEFCC”) introduced new emission norms for power plants, setting limits for major pollutants.

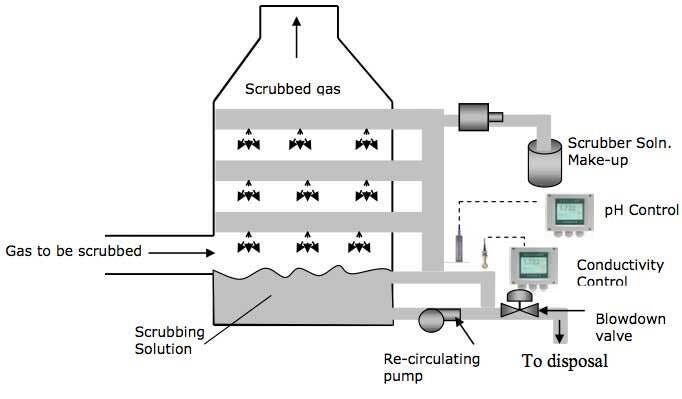

One of them was sulphur dioxide (SO₂). To cut SO₂, it asked power plants to set up Flue Gas Desulfurization (FGD) units – essentially scrubbers – in coal plant chimneys. The system would spray emissions with a limestone slurry, which would react with sulfur dioxide, trapping it before the gas was released.

The government then identified coal units across India to be retrofitted with these scrubbers, and gave them an aggressive deadline: they had two years to comply. Those systems would have to be in place by 2017.

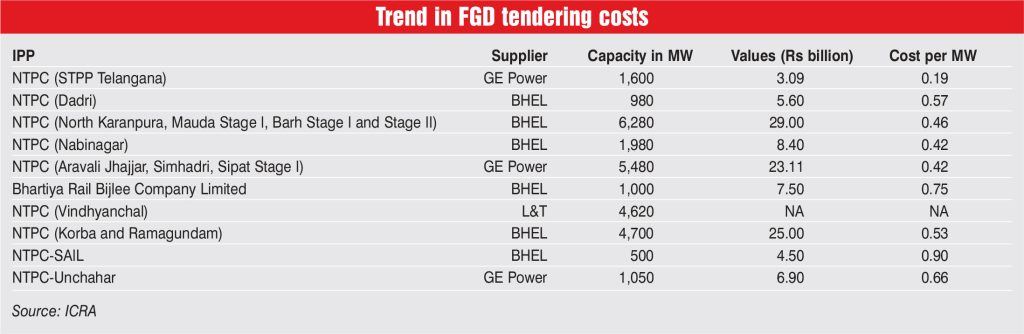

There’s only so much the mandate could do, however. Even as the 2017 deadline loomed, hardly any plant had installed an FGD. It was simply too large an investment — any plant operator would have to shell out hundreds of crores on such systems. Worse still, the smaller a plant was, the more expensive the system would be. Meanwhile, the investment would generate little to no upside for anyone that ran a plant.

Naturally, power producers dragged their feet, pleading for more time. The government relented. The deadline was pushed out.

It simply seemed impractical to instantly slash pollution all across the country. It made more sense to be stricter in areas where pollution was getting genuinely bad, and then work one’s way to the rest of the country. Slowly, the idea of “phased, category-wise” deadlines took hold. By March 2021, the MoEFCC came up with three tiers, based on urgency:

Category A: Units within 10 km of Delhi-NCR, or any other city with over 1 million people.

Category B: Units within 10 km of areas with high pollution, or cities that continually failed national air quality standards.

Category C: All other units, in more remote areas.

Each category was given its own deadline: Category A plants had to install FGDs by 2022, Category B by 2023, and Category C by 2024.

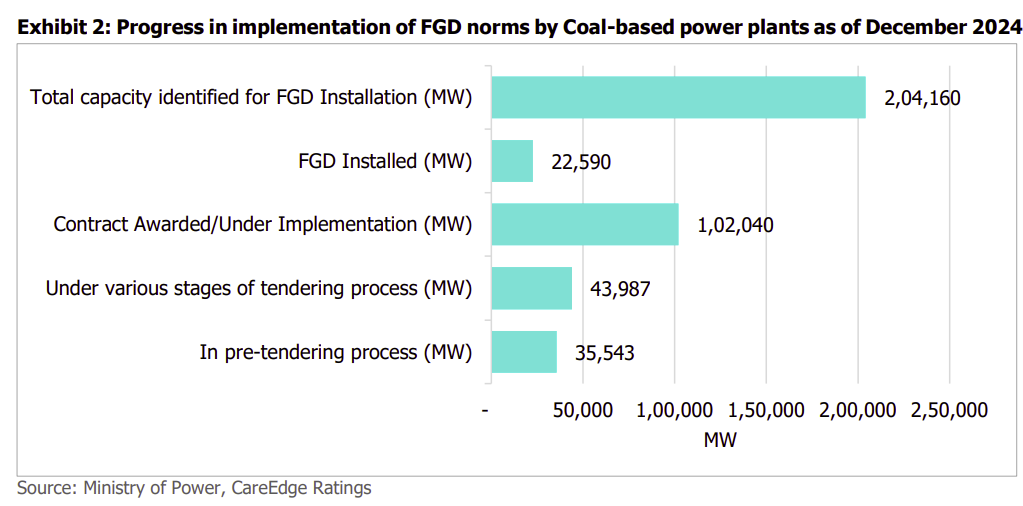

On the ground, though, progress remained slow. Most power stations made little tangible progress beyond initial paperwork. By December 2024 only about 11% of our thermal power plants, by capacity, had installed such systems. The rest were stuck somewhere in procurement.

Those deadlines were extended repeatedly. By December 2024, the deadlines for Category A plants was pushed to 2027, Category B to 2028, and Category C to 2029.

But with this, a new reality was slowly becoming clear. This wasn’t a problem you could solve with simple mandates and deadlines. After nine years of trying, nearly 80% of the planned retrofits remained incomplete. We needed a change of track.

It’s in this context that the government made a tough choice.

The sulfur exemption decision

On July 11, 2025, the Environment Ministry issued an order exempting Category C plants entirely from having to meet the SO₂ emission norm. These units — roughly 400 coal-fired boilers totaling ~145 GW capacity — no longer have to install FGDs, as long as they maintain their tall chimneys as per older rules.

Category B plants, too, got partial reprieve. They shall now be judged case-by-case by an expert committee, and if their emissions aren’t particularly bad, they’ll potentially be given more time or leniency. Its only Category A plants — those near big cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, etc., which make for barely 10% of our thermal power production – which still need to comply by December 2027.

How should you see this shift? This is what the government says:

“The revised sulphur dioxide emission policy is not a rollback of environmental safeguards, but a pragmatic, scientifically justified shift toward more targeted, cost-effective, and climate-coherent regulation.”

The problem boiled down to the economic costs of such a project. To retrofit hundreds of coal units with FGDs is a project that would take ₹1.3–1.8 lakh crore. Roughly two-thirds of this cost would have to be borne by public sector enterprises like NTPC.

If these entities were to make such a huge expenditure, where would the money come from? There was only one way to curb SO₂ emissions in a way that would make financial sense — recouping those costs from customers. By some calculations, consumers would have to pay an extra ₹0.20–0.50 for each kilowatt-hour if every plant installed a scrubber. And that would practically be impossible.

India’s electricity rates are set through a complex mix of long-term contracts, regulatory decisions, and political barriers. To justify higher rates, a company like NTPC would have to renegotiate purchase agreements, justify a change in prices to the CERC, fight challenges from state governments and electricity regulators, and survive political turmoil. If they didn’t succeed, their plants would become unviable, and their debt burdens would shoot up.

For context, just by exempting the Category C plants, the government effectively saved consumers ₹19,000–24,000 crore per year in potential tariff hikes.

On the flip side, according to the government, the harm of SO₂ emissions was limited.

The Environment Ministry claimed that there was no significant difference in ambient SO₂ levels between areas with FGD-fitted plants and those without. That is, the FGDs simply did very little to change health outcomes. Even if power generators bore all those costs, that would do little to improve health outcomes.

Is this actually true? We simply don’t know.

This has received some criticism, however. The Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) released a report claiming that these conclusions are erroneous. It criticised the government’s findings on ambient SO₂ levels, claiming that there were flaws in how these were measured. The think tank asserts that FGDs made a serious dent in sulphate concentrations as far as 200 km away from a plant.

What led to the policy revision?

Ultimately, though, that debate is secondary. Even if everyone concurred on the effects of SO₂ emissions, they would have to face hard truths about economics and governance. Ultimately, it’s just hard to make policies that actually work.

If it were easy for power plant operators to cut down SO₂ emissions, a mere rule would do the job. But this was, in fact, so difficult that compliance was effectively more challenging than not complying.

These upgrades would immediately hurt the financial viability of a thermal power producer. Many plants did issue tenders for FGDs, only to realise that bid prices were much higher than expected. There were serious issues with many — from low participation to supply chain issues — potentially requiring more rounds of tendering as well.

If those tenders would go through, they would face serious down time — around three to six months. This would hurt their top-line, and would put them at risk of violating their power purchase agreements.

Would they recover any of that money? That would depend on how well they could navigate the system. They would need regulatory permission to pass on those costs to consumers. It took till 2019 for the first round of clearances to come through — when the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission allowed FGD costs to be added to tariffs. But there were other layers to get through. State regulators moved slowly, while distribution companies (the ones actually buying power) balked at the prospect of higher rates.

What would happen if you dragged your feet, on the other hand?

So far, there was little punishment for missing deadlines. The government seemed to understand just how difficult this all was, which is why it was happy to extend deadlines for compliance. The idea of imposing fines emerged only in 2022 — and those, too, were largely theoretical. As of mid-2025, not a single plant had been penalized for SO₂ norm violations.

So, in some ways, non-compliance was actually the easier route to take.

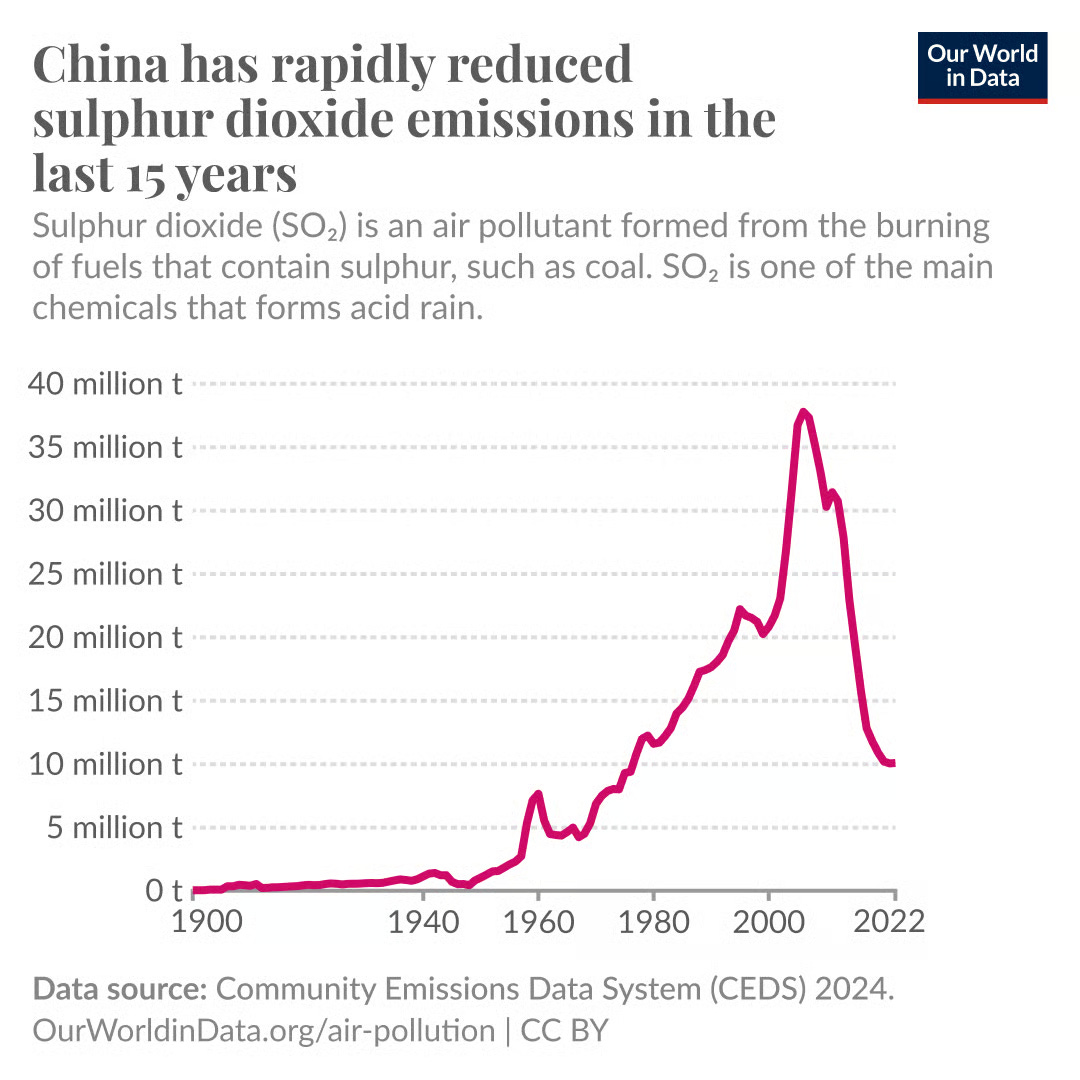

There are countries that have been more successful than us. Consider China’s experience: a couple of decades ago, China’s thermal power sector was as dirty as India’s. Yet China managed to retrofit over 90% of its coal plants with FGD technology by the mid-2010s, slashing SO₂ emissions by more than 70% in just 15 years.

How? Beijing took a “carrot and stick” approach. It punished non-compliance, but crucially, it encouraged compliance too.

China established hefty fines and even criminal liability for plant managers who violated emission standards. Meanwhile, it offered a tariff premium for coal power with FGDs: plants received extra payment per kilowatt-hour if they operated scrubbers. The government also ramped up domestic manufacturing of FGD equipment and ensured there were enough engineering firms to make installations at scale.

If there’s a lesson for India, it’s this: some problems are too hard to solve by just telling businesses to do something. For good policy-making, you need to pre-empt where your plans can fail, and nip those problems in the bud.

A revision or a reset?

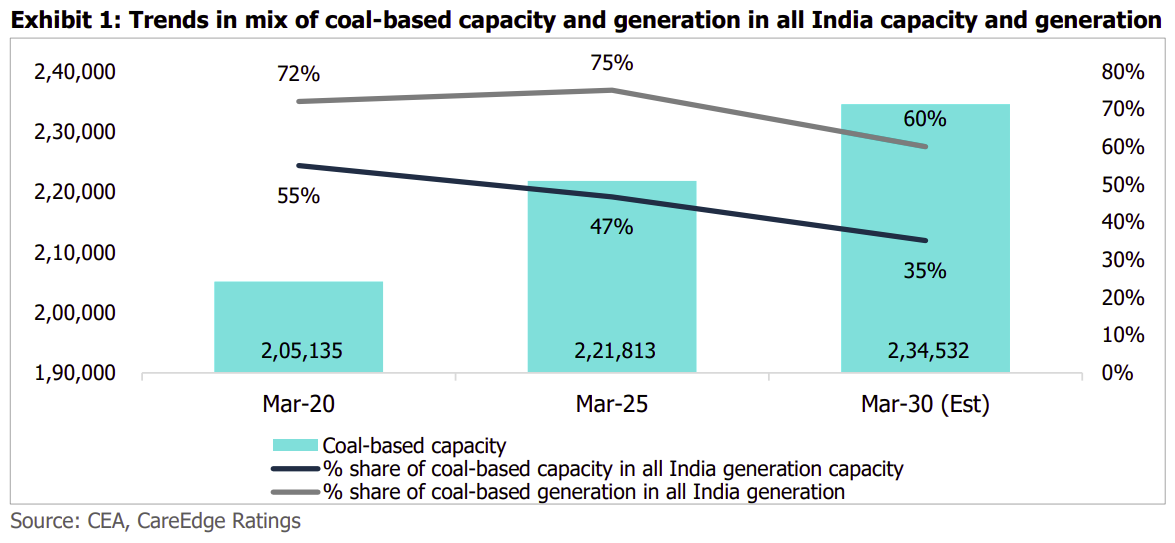

This moment underscores the broader crossroads that India’s energy transition is at. While we’re making tremendous progress in setting up new renewables projects, coal still forms our energy backbone – accounting for about 75% of electricity generation today.

Thermal power, in India, is simply too vast, complicated and important to experiment with. Retrofitting them at scale, at speed, and without crushing consumers or bankrupting operators, is a Herculean task. In some ways, it’s harder to shift the needle on this legacy industry than to create something new from scratch.

For now, the exemption signals that India is choosing to protect its grid and its consumers over environmental gains. The real question, though, is what comes next — can we use this breathing room to build a smarter path forward, or are we simply kicking the can down the road?

₹3,000 Cr Solar IPO Explained

Emmvee Photovoltaic Power Limited recently filed its papers for an IPO worth ₹3,000 crores.

To us, this created a fantastic window into a world we hadn’t explored before — on how those blue panels on rooftops actually get made, what are the drivers and the risks of manufacturing them, and the financials that come with it.

That’s what we’re going to parse through with you, today.

How Solar Panels Come to Life

Making solar panels is a sophisticated process: one that transforms ordinary sand into electricity-generating technology. This happens over five steps:

To start with, sand is treated with energy-intensive chemical processes, until it turns into ultra-pure polysilicon.

Next, all that polysilicon is melted, and cooled into perfect crystal ingots. These are sliced into wafers thinner than paper, with extreme precision — any imperfection, here, ruins the final product.

Those wafers are then turned into actual solar cells. Workers create electrical contacts by applying a silver paste, while the back surface is covered in an aluminum paste. This is all heated and treated with chemicals, to create the electrical properties that turn sunlight to electricity.

One cell can only create so much electricity. And so, these are bunched into modules; cells are arranged, connected with thin wires, and sealed between protective glass and polymer layers. Aluminum frames provide structure to the entire module, while junction boxes handle electrical connections.

Finally, these modules are installed, deployed, and plugged into the grid — work that happens close to where the panels will be used.

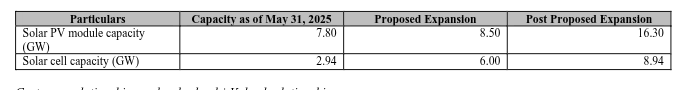

Emvee operates in the third and fourth of these steps: it takes silicon wafers, and turns them into modules.

What Emmvee Actually Does

Emmvee calls itself "the second largest pure-play integrated solar photovoltaic module and solar cell manufacturing company, and one of the largest solar PV module manufacturers in India."

The company runs four manufacturing facilities in Karnataka. Together, these can manufacture 7.80 GW of modules and 2.94 GW of solar cells a year. For context, India has a total solar manufacturing capacity of 82 GW for modules and 23 GW for cells as of FY25. So the company effectively controls a tenth of the market.

But that will only tell you so much. To really understand the company, you have to understand one thing: this is a market where everything is in flux. It’s marked by everything from intense technological change, to heavy government involvement, to the world’s greatest manufacturing whale — China.

The technology race

Any business in this space must contend with one fact: solar cell technology is still young, and is evolving rapidly. New technologies keep coming up, each one harder to make than the last, even as they offer higher efficiency.

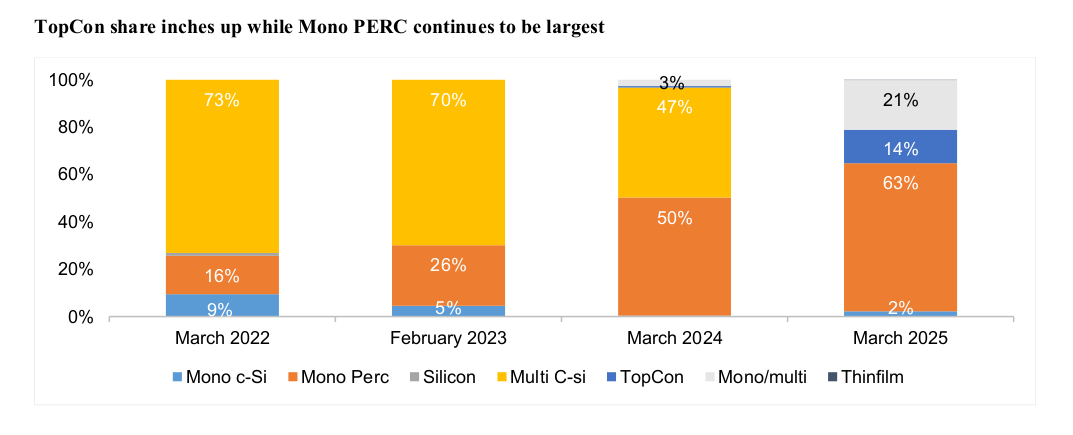

Until recently, multi-crystalline silicon cells dominated the market. They were relatively cheap to produce, but could only convert 15-17% of the sunlight hitting them into usable electricity. However, as the industry matured, efficiency became paramount. In just a few years, multi-crystalline cells have virtually disappeared from the Indian market, dropping from 73% market share in March 2022 to almost nothing by 2025.

Right now, Mono PERC (Passivated Emitter and Rear Contact) technology is the industry workhorse, achieving efficiencies of around 23%. With a 63% share, this currently dominates the Indian market. Most manufacturers have built their production lines around this process.

But this technology, too, is fast approaching its theoretical efficiency limits. If past experience is anything to go by, it might quickly disappear too. So what comes next?

A promising new technology is TOPCon (Tunnel Oxide Passivated Contact). TOPCon cells can achieve efficiencies over 25%. Equally, they’re much better in low light conditions, maintaining 97% efficiency even when sunlight is in short supply. They also lose less efficiency when they get hot — a crucial advantage in India's climate.

At the same time, manufacturing TOPCon cells is much harder than PERC. It takes more expensive equipment, and is harder to master. But if you can manage it, those very things become a moat.

That’s the heart of Emvee’s promise: it wants to stand out for how advanced it is. It’s an early adopter of TOPCon technology. In fact, its Bengaluru facility is one of the country's largest TOPCon solar cell manufacturing facilities. At the same time, though, it also produces traditional Mono PERC modules for price-sensitive customers.

But with this comes a hidden challenge: whenever the next technological wave comes around, Emvee will have to either pivot or perish.

Government support

This is an industry that lives and dies by government policy.

To most solar cell manufacturers, the government is likely to be one of the biggest buyers there is. But the government doesn’t just buy from anyone. It has an “Approved List of Models and Manufacturers” (ALMM): a list of pre-approved domestic manufacturers who meet stringent quality and testing standards. Government solar projects can only use panels from them.

A system like ALMM has a dramatic impact on the industry.

Consider this: for much of FY 2024, the government had suspended its ALMM program. Then, on April 1, 2024, the ALMM came back to life. Overnight, the cheaper Chinese imports that had dominated the market were cut out. Suddenly, across the board, Indian manufacturers started charging premium prices. All their revenues suddenly leapt by many multiples.

Emmvee is an ALMM-listed manufacturer. They have clear access to this protected market segment. And in the last couple of years, that has done wonders for their numbers.

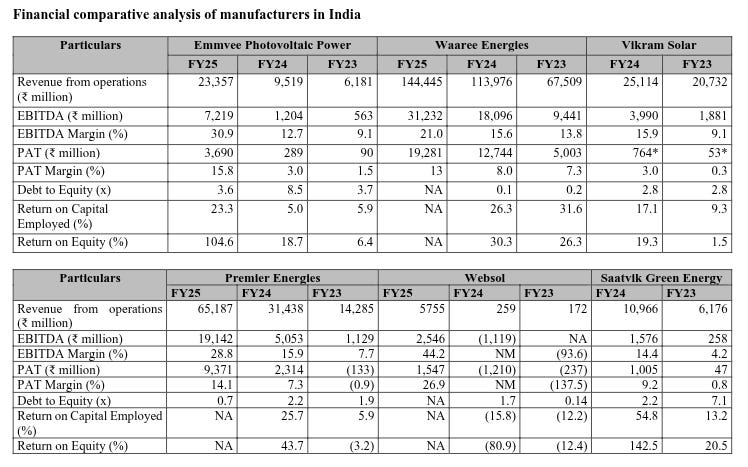

Take their revenue: in FY 2023, the company generated ₹618 crores in revenue from operations. This grew to ₹952 crores in FY 2024 — a 54% year-over-year increase. But the very next year, in FY 2025, their revenue reached ₹2,336 crores, a 145% increase from the previous year.

As revenues grew, the company's profitability improved as well. Its EBITDA margins improved dramatically from 9.1% in FY 2023 to 12.7% in FY 2024. They surged to 30.9% in FY2025.

With that, its PAT margins went from a modest 1.5% in FY 2023 to 3.0% in FY2024, and then achieved 15.8% in FY 2025. And with that, their absolute profits have zoomed at a stunning pace. From ₹9 crores in FY2023, in just two years, its PAT surged to ₹369 crores in FY 2025.

Much of this is a result of government policy. If anything, that will only become more important in the future. The government is now coming up with ALMM-II, starting from June 2026. With this, government projects will have to use modules made from domestically manufactured cells. Businesses can’t just buy cells from abroad and assemble them into modules. That will, in short, be a whole new niche for Indian manufacturers to exploit.

The China problem

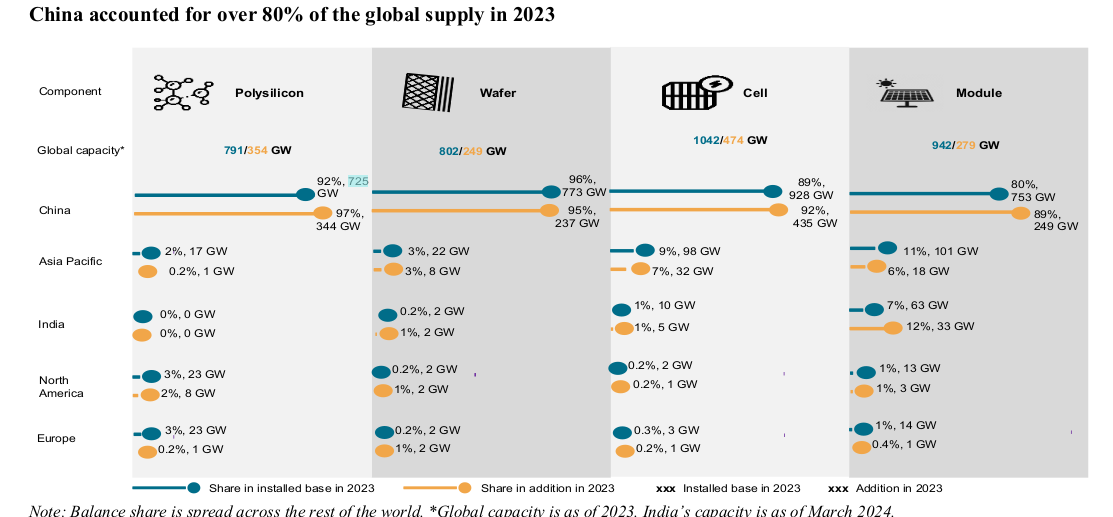

Like with so much else, China basically controls the world’s solar manufacturing industry from start to finish. It controls more than 80% of the capacity in each step, including a massive 96% of the wafer-making stage.

Emmvee, like anyone else in this space, buys a lot of the raw material it needs from China. In FY 2025, for instance, 55.73% of all their raw materials came in from China.

As so many other industries are finding out to their peril (like auto manufacturers, as we spoke about previously), this dependence can be a severe risk. One policy change from either side could suddenly put this business at risk. India, for instance, could suddenly slap import duties and restrictions. China, meanwhile, could just as easily choke outbound supplies. Either would wrap their operations in uncertainty and volatility.

Understanding the IPO

Why is Emmvee going for a ₹3,000 crores IPO?

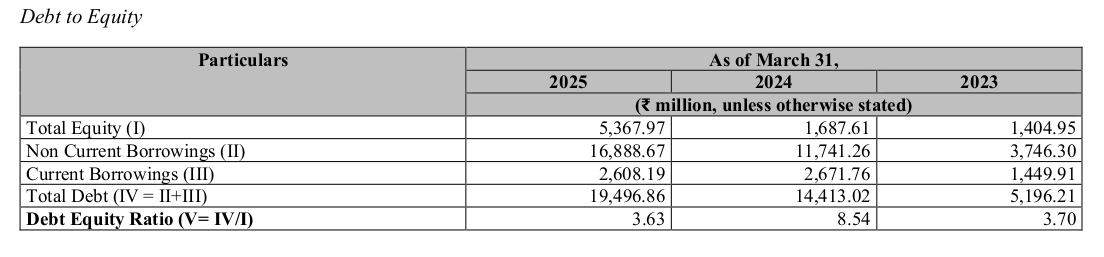

It’s primarily trying to repay its debt.

Right now, Emmvee (along with its subsidiaries) have outstanding borrowings of over ₹2,700 crores. They borrowed a lot of this money over the last few years, to set up plants for TOPCon manufacturing facilities. This IPO will help them pay off more than ₹1,600 crore of this debt load.

Right now, the company has a debt-equity ratio of 3.63. That’s very high. For every ₹1 that belongs to the company’s shareholders, the company currently owes ₹3.63 in debt.

But that could change quickly. Once this IPO is done, its debt load will look a lot smaller. Meanwhile, if its revenues keep picking up at their current pace, they’ll suddenly seem to justify that massive debt load.

So, how should you see the company?

Emmvee’s story is both exciting and precarious. This IPO presents a rare chance to buy into a company that’s riding two powerful tailwinds — a domestic policy framework that favors local manufacturers, and a technological leap that could make it a leader in India’s solar push. At the same time, it’s a business bound to the whims of policy, and vulnerable to China’s overwhelming dominance. It’ll also keep playing catch-up as new technologies emerge.

There isn’t a straightforward story to tell here. To invest in the company, right now, is to bet on government support holding steady, on Emmvee keeping pace with innovation, and on India building a solar industry that can thrive despite its dependencies.

But if those bets pay off, Emmvee could just be a pivotal player in the country’s energy future.

Tidbits

Larsen & Toubro’s green energy arm will build, own, and operate a new plant at IOCL’s Panipat refinery that’ll supply 10,000 tonnes of green hydrogen per year for 25 years. The project directly aligns with India’s National Green Hydrogen Mission, which wants to turn the country into a global production hub. It will also help IOCL reduce emissions at one of its largest refineries, showing how legacy fossil fuel players are now becoming hydrogen buyers.

When we broke down green hydrogen earlier, we said India’s dream was bold — 5 million tonnes of clean hydrogen by 2030. And this is just another example of its commitment.

(Source: Business Line)Adani is tightening its cement play. The NCLT has approved the merger of Adani Cementation into Ambuja Cements, consolidating the group’s cement empire under one roof. Just last month, Ambuja crossed 100 MTPA in capacity, largely through M&As. This merger takes things further, streamlining operations, unlocking mine access, and absorbing under-construction sites from Adani Cementation.

We explored the cement industry through their financial results. Let’s see how this news adds to our next addition

(Source: Business Line)Now, India's oil regulator, PNGRB, has mandated that city gas distributors charge a uniform rate for household piped natural gas, eliminating tiered pricing based on consumption. This move aims to prevent misuse of subsidized gas and ensure fair pricing for all domestic consumers.

We questioned whether CNG is losing its spark, especially following APM gas allocation cuts. Maybe this could help, only time will tell.

(Source: Business Standard)Microsoft is likely to sign the European Union’s voluntary AI code of practice, aiming to align with the EU’s AI Act by enhancing transparency and copyright compliance. In contrast, Meta has rejected the guidelines, citing legal uncertainties and concerns over potential overreach

AI is growing so fast, that just a monthly round-up doesn’t seem enough to cover all the developments.

Source: (Reuters)Reliance Retail has launched Ajio Rush, a four-hour fashion delivery service now available in six major Indian cities, including Mumbai, Delhi-NCR, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Chennai, and Ahmedabad. Ajio Rush leverages Reliance’s existing warehousing and logistics network to enable quick turnarounds without the high costs associated with newer quick commerce players.

There’s a new entrant to quick commerce, and it’s going beyond groceries.

(Source: Business Standard)

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Prerana.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉