Can bad eyes make for a good business?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Lenskart hits the public markets

Inside India’s Largest REIT IPO

Lenskart hits the public markets

One of India’s most exciting new-age companies, Lenskart, has just filed its papers for an upcoming IPO. It plans on picking up ~₹2,150 crores from the public market through a fresh issue, while its promoters and investors will be selling off ~13 crore shares.

Eyewear makes for a curious market. On the one hand, it’s a market that has existed for centuries — people have always had bad eyes, and we learnt how to solve that problem a long time ago. And yet, the market is more relevant than ever. We’re in the middle of an “eyesight epidemic”; with an aging population and lifestyle issues, more Indians have eyesight problems than ever.

But can bad eyes make for a good business? Let’s find out.

Betting on the eyewear market

Glasses are an interesting thing to sell; they’re simultaneously medical products and fashion products.

On one hand, a company like Lenskart serves a medical need.

To bet on the company is to make a slightly morbid prediction: that people’s eyes are getting worse. There are, sadly, reasons to believe that’s true.

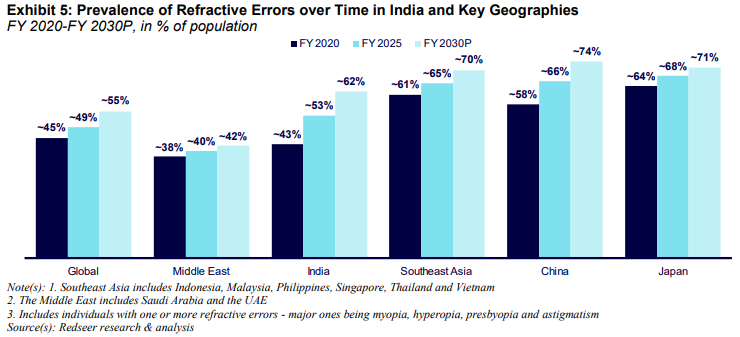

Around the world, more and more people need glasses each year. That’s partly just because populations are aging all over the world. But it’s also because our lifestyles are getting worse: we’re staring at screens too much, sleeping too little, and are living amidst too much pollution. Because of this, our eyes have become worse than they have ever been. In India, for instance, in just the five years between FY 2020 and FY 2025, the prevalence of eye issues has gone from 43% to 53% of the population.

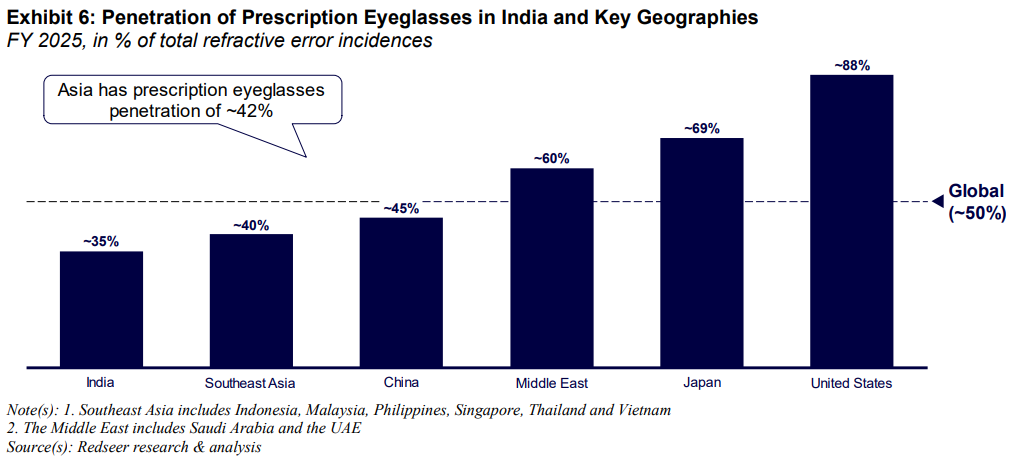

It’s not just that more people need glasses, though. Right now, many people who should wear glasses don’t — and that group, too, presents an opportunity. In India, for instance, an estimated ~35% of those with bad eyes actually wear prescription glasses. Many simply don’t know that they have issues, while others can’t afford them — or even access them. Over the next decade, as awareness and incomes rise, that gap might shrink.

According to Redseer, in just the coming five years, the prevalence of eye problems will increase even further — by then, 166 million additional Indians will need glasses. At the same time, eyeglass penetration will grow, from 35% to 41%. That is, in just five years, roughly 111 million more people will regularly wear glasses. There is, in short, a lot of fresh demand to unlock.

But that’s just new customers. There’s a whole other dimension to this, however — eyewear is also a lifestyle business.

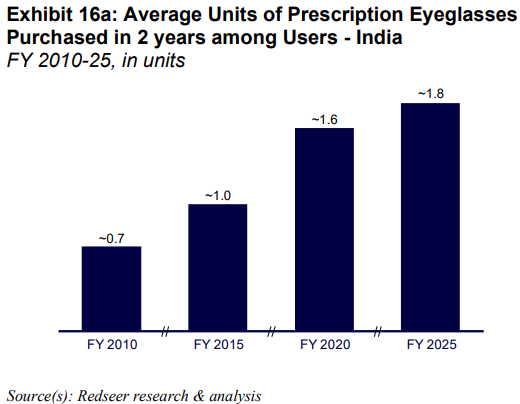

Eyewear companies don’t play the game of medical representatives and tender-based procurement that are common elsewhere in the medical devices industry. To those that need glasses, eyewear behaves more like clothes or shoes. People buy them as a fashion statement. They purchase multiple pairs at a time, to suit different styles, occasions, or moods. They demand larger collections, and greater customisation. If you can keep up with trends, though, this presents a huge opportunity. Customers are willing to buy more often, and pay a premium for it.

In 2010, for instance, customers bought an average of 0.7 glasses every two years. Now, they buy 1.8.

It’s this complex game that Lenskart wants to play — and win.

What does Lenskart bring to the table

At the end of the day, though, eyeglasses have been around for at least seven hundred years, if not more.

What makes Lenskart an exciting business, then? Why is it a “disruptor,” rather than someone continuing a centuries-old profession?

There are many things the company points to. Fundamentally, though, there are two things that make Lenskart an interesting company: (a) it controls most of its supply chain, and (b) it has blended technology into large parts of its processes.

Vertical integration

Lenskart’s first promise is efficiency.

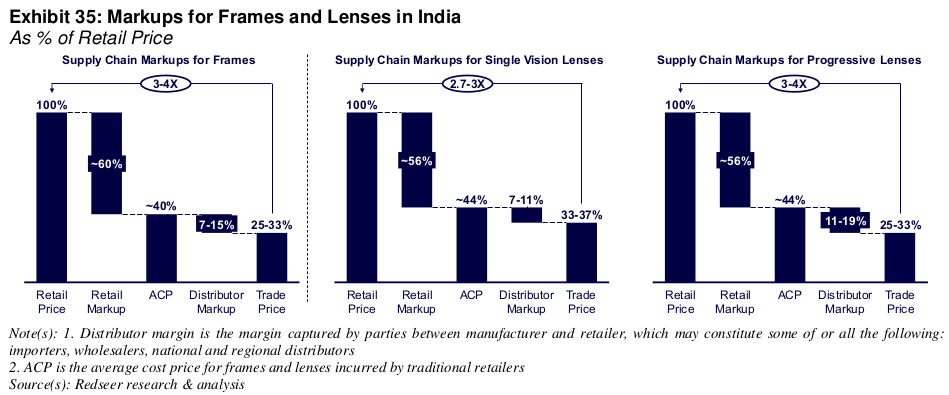

Traditionally, selling glasses was a localised, fragmented business. At least in India, the industry was marked by thousands of independent stores that sourced frames and lenses from various distributor networks — often from abroad — and then relied on local workers to manually cut and fit the lenses. There were multiple layers of middlemen all through the supply chain, each adding markups and time lags.

To a customer, this showed up in higher costs, errors and delays. Everything from frames to lenses would sell at as much as 4x the trade cost. This made eyewear feel expensive even to middle-class families.

Lenskart collapsed the entire value chain into two centralised megafactories — in Bhiwadi, Rajasthan, and Gurugram, Haryana.

These factories take in orders from stores all across India, and make everything in-house. For one, this lets procure components — frames and glasses — in bulk, at cheaper rates. This cuts out many layers of intermediaries, and reduces the bottlenecks the company runs into. All-in-all, that shows up as a 35-40% reduction in its costs.

With the scale the company runs at, it can automate many of its processes. It doesn’t need to rely on manual labour to cut and fit its lenses. For one, that allows it to work instantaneously — when an order is placed, its systems start cutting glasses within minutes. Moreover, it doesn’t have to bank on the skills of its workers; it can ensure that it sticks to tight quality standards for relatively cheap. In fact, the more orders the company gets, the less it spends per pair of glasses — after all, once you already have a machine, one extra pair doesn’t cost much.

This makes the company structurally different from a traditional eyewear retailer. Where a traditional shop would take 5–7 days to turn around a pair of glasses, Lenskart can push them out within a space of a single day — at least in 40 major cities. And it does so for cheap — per pair of glasses, in fact, it makes a margin of nearly 70%.

Technology focus

Beyond this, the company focuses heavily on technology. And while that can often sound like an empty buzzword, a lot of Lenskart’s technology solves specific, tangible customer pain points. Here are a few examples:

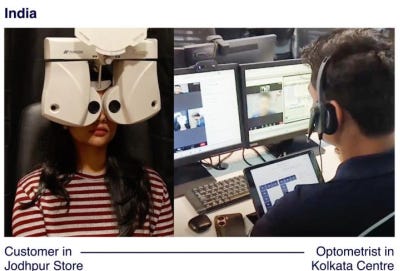

Remote optometry: To run an eyewear business, you need eye tests — for which, you need skilled optometrists. Unfortunately, they’re hard to find, especially outside big cities. Getting one on roll can be a challenge from most eyewear retailers. This is a big reason for eyewear penetration being so low in India — we have just 60 eyewear stores for every million people, compared to voer 100 in South-East Asia.

Lenskart solves this through remote optometry. That is, if you get an eye test in a Lenskart store, often, the equipment is being controlled remotely by an optometrist sitting in Gurugram or Kolkata.

This breaks a massive geographic barrier: Lenskart can jump into smaller, underserved markets, without first having to hunt for skilled workers. It can expand quicker, and deeper. In FY25 alone, in fact, it carried out over 13 million eye tests this way.

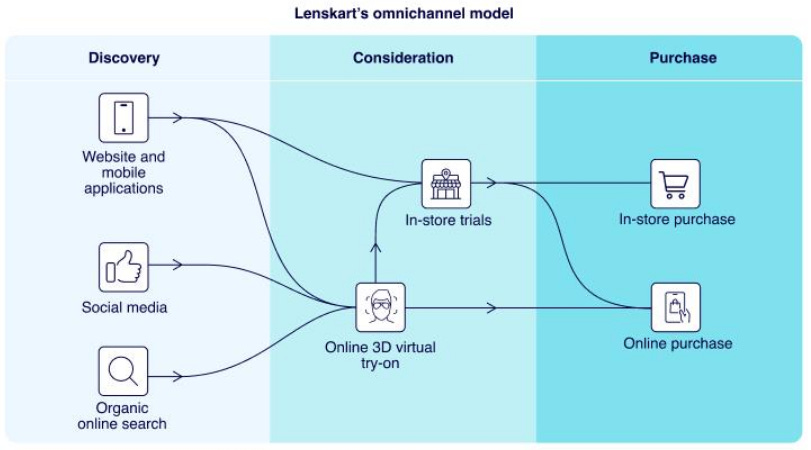

Seamless inventory and orders: Lenskart prides itself on “omni-channel retail”: that is, it tries to offer a unified experience across online and offline channels.

That’s harder than it seems. When retailers try selling something both online and offline, the two often end up in silos. Different channels can behave like different businesses — with two completely disconnected inventories. This creates severe stocking problems, losses in revenue, and a lot of confusion besides. Lenskart, however, has managed to marry the two together. It integrated its entire retail network — physical stores, online app, and website — onto a single unified inventory management platform.

Along with that, the company can maintain other data on a customer — such as a customers’ past eye test results or prescriptions — all of which can be retrieved no matter how you interact with the company.Because the back-end is all integrated, Lenskart can practically turn its retail stores into showrooms-cum-consultation studios. Its entire inventory is available online anyway. To customers, different channels can serve different purposes — they can, for instance, short-list designs on the app, go to a store for an eye appointment, figure out what fits best, and then place an order online.

Where the company is, today

Lenskart is still a young, growing company.

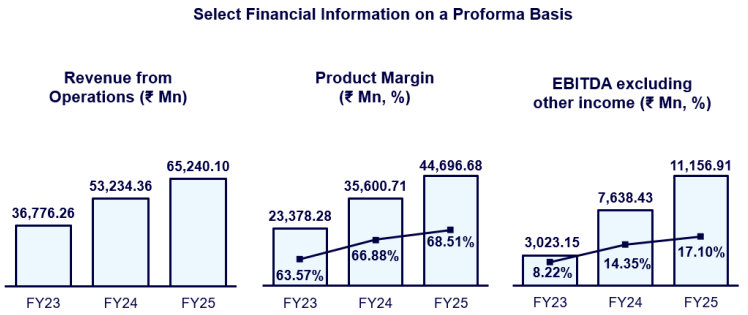

Its operational revenues crossed ₹6,600 crore last year. Just a year ago, they were just over ₹5,300 crore. And a year before that, they were much lower, at under ₹3,700 crore. That said, its growth has fallen in just these two years from ~43% to ~22.5%. The days of breakneck growth may already be behind it.

What the company is losing in top-line growth, however, it might be making up in improving profitability. In the last two years, it pushed its gross margin up by nearly 500 basis points — to 67.9%. For every ₹100 it earns by selling a pair of spectacles, that is, it spends just over ₹30 making them. Of course, they don’t just spend money to make spectacles. But even once you count in all those other expenses, its EBITDA margins have now crossed 14.6% — more than twice of the 6.86% they were making just two years ago.

These rising margins allowed the company to book its first ever annual profit last financial year: of ₹297 crore.

There’s a lot that’s happening within the company. But two things caught our eye:

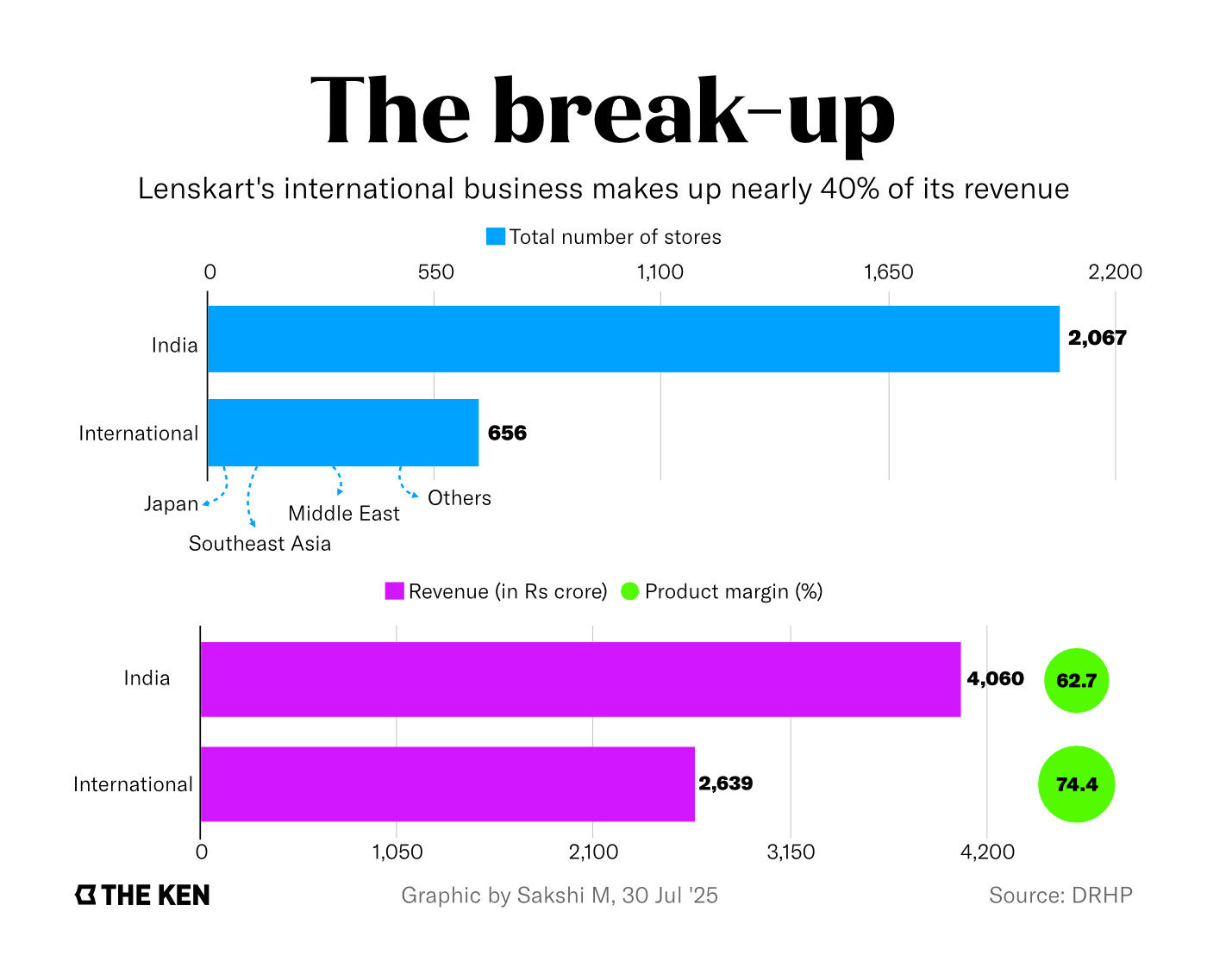

International expansion: Lenskart is slowly expanding abroad. It’s not rushing this either — it has chosen specific markets, like UAE, Singapore and Japan, which work somewhat like the Indian market. Foreign markets are less price conscious than India — and give the company better margins. Its gross margins abroad are ~74%, compared to ~63% in India. And so, foreign markets are already making for a decent portion of its revenue.

To fuel this expansion, the company has been lapping up foreign brands. It has just acquired the Japanese eyewear brand Owndays — reportedly after offering to do so five different times. This has given it a massive foothold across East and South-East Asia. The Ken has an excellent piece on its expansion.

Wholly owned stores: Until recently, most Lenskart stores were actually run by a franchisee — Dealskart. Late last year, however, Lenskart absorbed the company, and made it a subsidiary. With that, hundreds of the company’s stores went from being franchisee-owned to company-owned. In fact, a major part of the IPO’s proceeds are meant to ease its transition into this new, company-owned model.

This is a trade-off. On one hand, this gives the company complete control over these stores, and removes the need to pay a commission to anyone. With that, its margins will look much better. On the other hand, the company’s costs will go up too — as it’ll have to absorb thousands of employees, and every expansion, from here, will need it to put out more cash.

The bottom line

We can’t tell you if Lenskart is a good investment. After all, any investment is only as good as the price you pay for it.

It is, however, a very interesting business. The company dove into an age-old market and found real value left on the table. It solved major legacy problems — bringing more efficiency and profitability to this industry. That allowed it to create a modern retail machine.

But how durable is this machine? Eyewear is a market with structural tailwinds, but also one that has been around for centuries. How far can Lenskart’s advantages in scale, technology, and brand take it? Will it continue growing at its current, breakneck pace, or is it now beginning to mature?

If you’re assessing this company, those are the questions you’re betting on.

Inside India’s Largest REIT IPO

The Indian markets are about to witness their largest-ever REIT IPO — as Knowledge Realty Trust (who we’ll call “Knowledge”) looks to raise a massive ₹4,800 crore from the public. This will be the third-largest IPO of any asset class in the year so far, ahead even of National Securities Depository Ltd. (NSDL), which we recently covered at The Daily Brief.

But that’s not the only reason we’re talking about it.

A bunch of you commented on our previous videos, asking us to explain what REITs and InVITs even are. And that’s a good question — most people have an instinct for what a company is, but these are completely different creatures. So we figured, why not do a proper 101-style deep dive? And since Knowledge is in the news right now, we’ll use that as our running example to understand how one actually works.

Just a heads-up though: this is also our first time digging deep into this space. We’re learning with you.

What are REITs?

A REIT, or a “Real Estate Investment Trust”, basically gives investors a way of investing in big-ticket real estate, without having to buy a building or worry about tenants ghosting on rent. Think of it like a mutual fund, but instead of pooling money to buy stocks, you're pooling money to buy real estate — office parks, malls, warehouses, that sort of thing.

Now how is this different from buying, say, a stock in a real estate company? Don’t both give you exposure to real estate? Well, yes and no.

When you buy a stock like DLF, you’re betting on their business — their ability to find land, develop projects and finally sell them at a profit (remember this). You aren’t just taking on risk on how well a property fares; you’re running a series of other risks — their approvals, how well they execute, their cash management chops, ability to time markets, and more.

When you invest in a REIT, you’re buying into a ready-made rent machine. At least 80% of a REIT’s assets must be completed buildings which are already leased out to tenants. The rent they pay flows back to investors like you. This gives you steady cash flow and much less construction drama.

But… what are you actually buying?

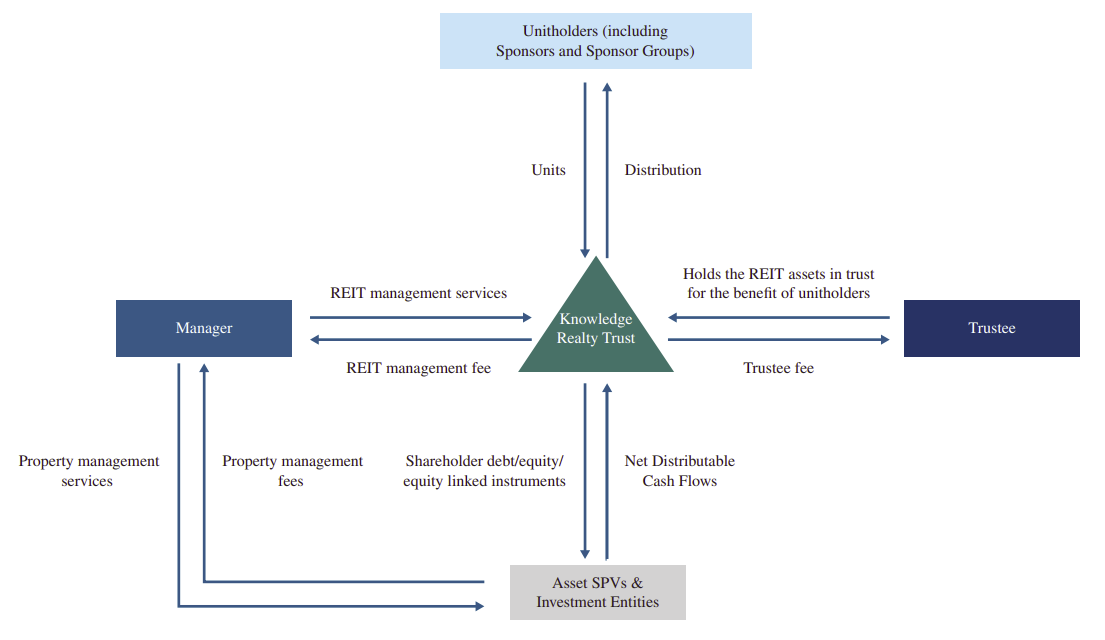

At the center of it all is a ‘REIT Trust’. That’s the legal entity that actually holds properties, and runs the show. These trusts are set up under SEBI’s rules, and operate under tight regulations. You buy “units” in this trust.

But there are others:

Sponsor: The original property owner or developer who kicks things off is called the “sponsor”. They’ve developed properties, and they now want to monetize them — and so, they transfer them into a REIT. Sattva Developers and Blackstone are the sponsors of Knowledge — and they’re entrusting a variety of properties, from Sattva Softzone in Bangalore to One BKC in Mumbai, to it. In exchange, they’re allotted units of the REIT.

SPVs, or “Special Purpose Vehicles”: A property doesn’t usually go directly to the trust — that would make things legally complex. Instead, a “special purpose vehicle” is usually created to hold properties — that’s a company that the trust owns shares in. That company actually holds the assets. The same trust could hold any number of SPVs to house different properties.

Trustee: Once a property goes to a trust, an independent third party is asked to look over the trust. It’s their job to ensure that the trust acts in the best interest of investors — they’re essentially a watchdog. Here, Axis Trustee Services will be taking up this job.

Investment Manager: While a trustee looks over a REIT, its day-to-day management — handling tenants, collecting rent, making acquisitions — is handed over to an investment manager. Basically, all the regular, operational work goes to them. Here, that’s the job of Knowledge Realty Office Management.

Unit Holders: That’s where you come in, as an investor. You buy units of a REIT (just like shares), and in return, you get a share of its income.

At first, the sponsors are majority-holders of the trust — a little like the promoters of a company. But then, the REIT does an IPO — either raising fresh money, or having sponsors sell off existing units they hold. That’s when you come in.

Any fresh money it picks up could be used to acquire new assets, increase the trust’s stake in its SPVs, or pay off any debt it took on to acquire assets in the first place. Once that’s all done, the REIT owns a portfolio of completed, income-generating properties.

According to SEBI’s rules, at least 90% of a REIT’s income has to go to unit holders. You can’t use it as a vehicle to hoard cash. Here’s how that works in practice: whenever someone pays rent, that goes to the SPVs. The SPV deducts its operating expenses, and sends money up the chain — for instance, by giving out dividends. The REIT takes that money, deducts its own expenses, and pushes the rest out to unitholders.

Evaluating a REIT?

Evaluating a REIT is a lot like evaluating any real estate project — just that it's a portfolio of them. You want to look for solid properties, with high demand, and tenants who pay on time — just like you would if you were buying actual real estate.

But since it’s structured as a REIT, there are a few nuances that come into play.

First, quality of assets

At the foundation of any REIT is a simple question: what properties does it own? Is it offices? Malls? Warehouses? Residential buildings? None of these are inherently good or bad, but they tell you a lot about the kind of cash flows you’ll get, and the kind of risks you might face.

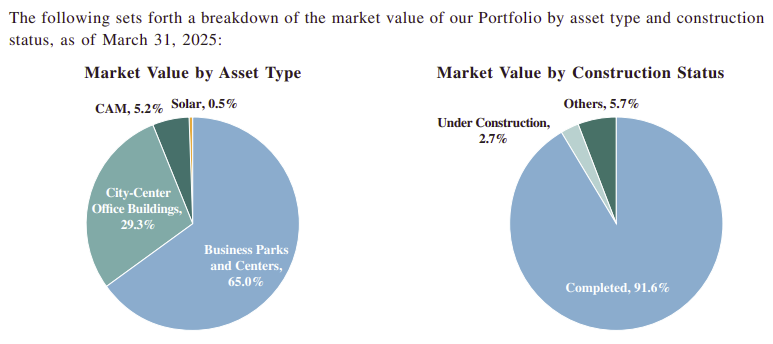

Knowledge, for instance, is a pure-play office REIT. It holds high-end, Grade-A commercial office spaces — no malls, no homes, no warehouses. To an investor, this is a bet on corporate India’s demand for workspaces.

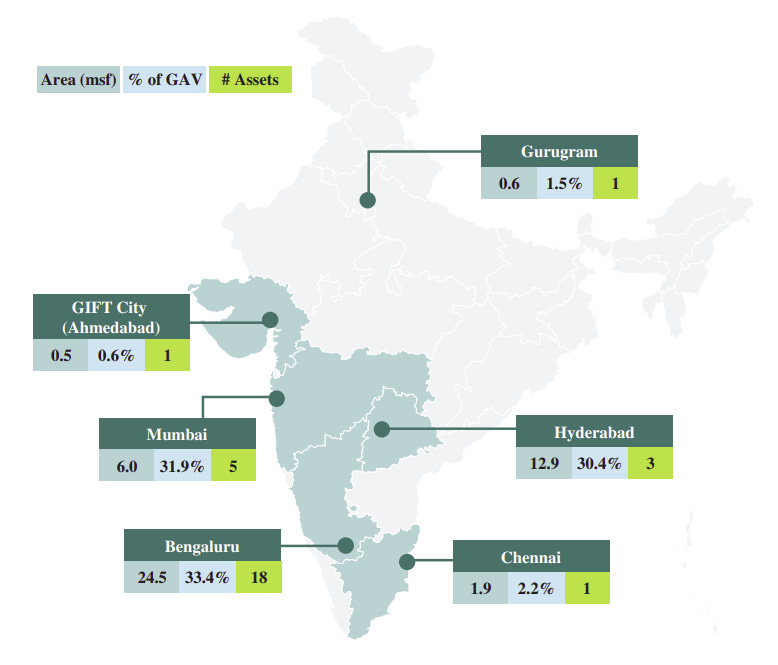

But as they say, real estate is about three things: location, location, location. You want to know where the properties are, and whether they’re in demand. Knowledge, for instance, owns about 46.3 million sq ft across 29 assets and 7 cities. But more than ~90% of those assets are concentrated in just three tech hubs: Bengaluru, Mumbai and Hyderabad. If you’re betting on the REIT, you need to know how comfortable you are with that.

Owning buildings is one thing. Having tenants is another. You want to know how well-occupied their buildings are, and how quickly that can change.

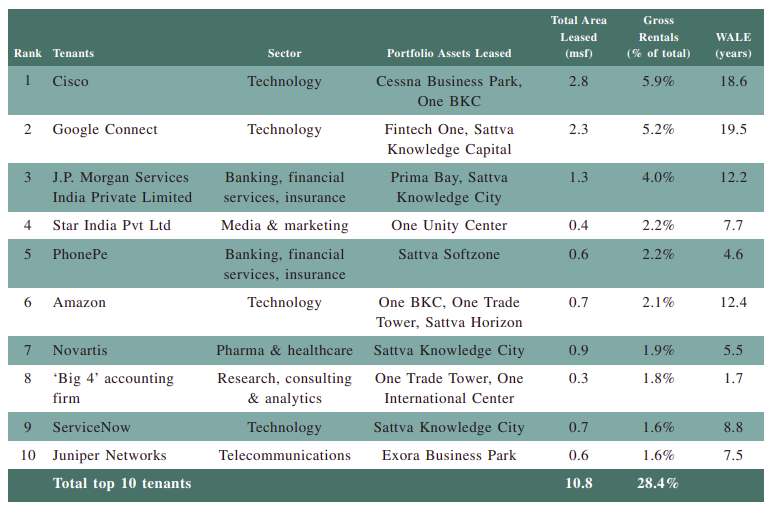

As of March 2025, Knowledge had a committed occupancy of 91.4% — solid but not maxed out. And ten of its tenants account for 28.4% of its rentals. For comparison, Embassy Office Parks REIT has 37.4% of its gross rental coming from the top 10. So there’s a little concentration risk here — if even one major tenant leaves, it could hurt cash flows meaningfully. But it’s not that bad.

Finally, you want to know a REIT’s development pipeline — how much of its portfolio is already earning money, and what’s still under construction. For Knowledge, about 92% is already leased and income-generating. A small chunk — less than 10% — is under construction or planned. Even if all those plans fail, it could probably survive.

Second, quality of tenants and leases

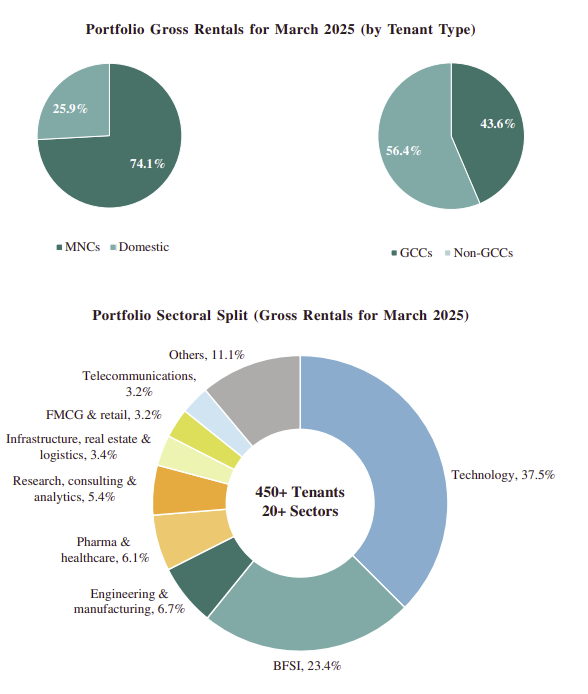

You want a REIT to have “high quality” tenants. Large, reliable companies, for instance, could fit the bill — chances are, they won’t default on rent or vacate on short notice. Here, Knowledge scores well. Around 75% of its rent comes from multinational corporations, with big names like Google, Amazon and JP Morgan. Most of them are tech or finance companies — so betting on the REIT is a bet on how stable those businesses are.

You also want to understand their lease terms. For instance, how long are these leases for? Do they have long lock-in periods? And so on.

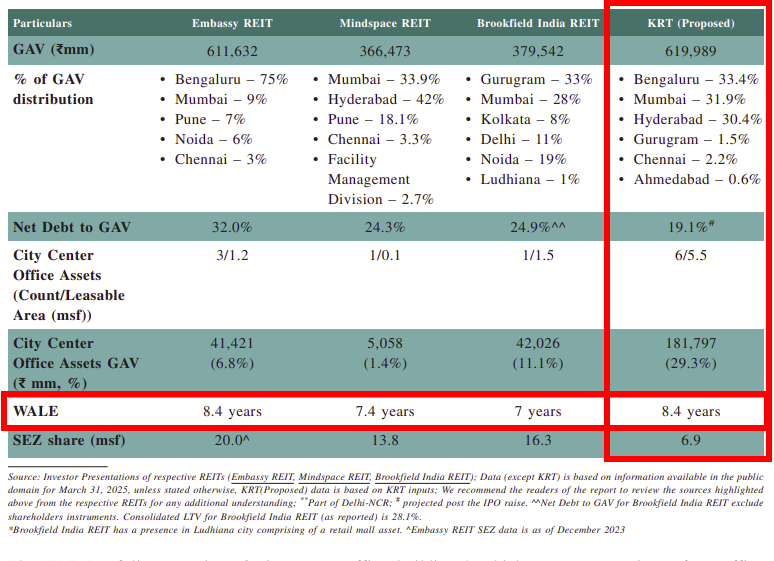

For Knowledge, the average lease term left — or “WALE” — is 8.4 years. That is, on average, tenants are contractually committed for another eight and half years. That should give you a sense of how long these tenants are likely to stick around.

Third, income stability and growth

If you’re looking at a REIT and not a property investment, you probably want predictable, rental-backed income. And so, you want a sense of how big the REIT’s cash flows are, and whether they’re growing. And you want to know how much of that money will come through to you, once everyone cuts their expenses.

Knowledge’s scale is massive. For FY25, it collected ₹4,147 crore in rent from all its properties. Of this, the ₹3,432 came through as “Net Operating Income” — what was left after taking care of all property-level operating expenses. That money would be passed to the Trust, where trust-level expenses and interest shall be deducted — leaving behind its “Net Distributable Cash Flow” (NDCF). By regulation, at least 90% of NDCF must be paid out.

That’s quite some money, and it’s growing. Knowledge’s rental income grew at a ~16.3% CAGR between FY23 and FY25. Not incredible, but solid, especially for a stable portfolio that’s mostly occupied. This might continue to grow – from future rent increases from existing tenants, leasing of vacant areas to new tenants, or even completion of its ~9 million sq. ft. of under-construction assets.

Final Thoughts

We’ve covered some of the top-level things to look at when analysing a REIT. But let’s be honest, there’s a lot more under the hood.

How levered is the REIT? How reliable will the distributions be over time? How aligned are the sponsors and management team with investors? Will they keep things clean when acquiring more assets, or will they overpay to offload sponsor-owned properties? And so on.

There are a million ways any investment can go wrong. You probably already know this about the stocks you own. But that’s also true about REITs. Ultimately, you’re entrusting others with your hard-earned money, and that’s something you need to be very careful about.

But we hope this helped you get just a little bit smarter about what goes into a REIT — and how to think about them beyond just the hype of a flashy IPO.

Tidbits

In a surprise, China’s manufacturing activity shrinks this month.

For the fourth straight month, the S&P’s purchasing managers’ index (PMI) has fallen to 49.5 from 50.4 in June. It missed a median forecast of 50.2 by economists. This also ties in with macro indicators — Chinese exports have fallen, and domestic demand isn’t high enough. China has been holding up well in the face of US tariffs, but the slowdown has been gradual.SEBI wants to change the structure of Indian IPOs.

SEBI has proposed increasing the allocation limit for institutional investors (from 50% to 60%), while reducing the limit for retail investors (from 35% to 25%). While IPOs have exploded in India lately, the rate of retail investors signing up for them has remained flat in the last 2 years. It is also considering including a larger proportion of pension funds and insurance companies in their limit for anchor investors — who are the investors who get to make bids right before the IPO.The government turns its watchful eyes on TCS’ layoff activity

Just recently, TCS laid off 12,000 people — 2% of their workforce. This has attracted the attention of the Ministry of Labour (both central and Karnataka), who wanted to know the reason behind this, as well as the deferment of hiring 600 professionals. TCS has assured them that the 600 will certainly be onboarded. The Karnataka IT workers’ union has also filed a complaint against TCS, alleging that the company violated the Industrial Disputes Act by firing more than 100 workers without government approval.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Kashish

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

There is fabulous book by Adam Grant which I am reading right now - Originals - which starts with the story of Warby Parker, the startup in the US which disrupted the eyewear and the lens business. They have done a fanstanstic job in their operations so far. Even in the world where generalists like Amazon exists which cater to almost all categories, I was mildly surprised that eye-wear couldn't be captured through it - so much so - that these folks (I think they were 4 graduate student cofounders) managed to amass a billion dollar valuation in an year (and I am talking about 2010s).

I do think these deep niches will bode well for someone like lenskart. Plus they indeed are building a seamless chain of automations to keep this order-to-delivery idea efficient, which is generally a good thing for the Indian consumers.

They must be itching for expansion as India is extremely price sensitive market, and somewhat desperately so - given they tried 5 times (!!) to acquite the Japanese eyewear firm. :)

Great article, learned lot of new things here...