Behind India’s changing Defence priorities

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

How India buys weapons

The big critical mineral mega-trends

How India buys weapons

Indian defense exports are becoming the talk of the town, especially after everything that happened over the last few weeks. In fact, India’s defence exports hit a record ~₹21,000 crore in FY2024 – nearly triple what they were in FY2021.

Indian defense stocks, too, have been soaring.

We wanted to understand what’s happening in the sector. Today’s defense boom didn’t come out of nowhere, after all. It’s the result of decades of changes: one driven by huge procurement exercises, geopolitical twists, and policy reforms. To understand the present, we need to revisit this long past.

So here’s a friendly historical primer on how India buys its weapons. Knowing this backstory will make the current buzz much clearer. One of these days, we’ll return to the other side of this tale: on how India sells its weapons.

Defense Equipment ≠ Consumer Goods

Buying a missile or a fighter jet isn’t like buying a car or a phone.

You can’t just stroll into a store and pick up a tank. In India, as in most countries, there’s just one real buyer for heavy-duty defense equipment — the government, through the Ministry of Defence (MoD). If the government isn’t placing orders, a defence company basically has no one else to sell to (sure, there are exports, but even those need government approval). In other words, if there are no government orders, there’s no demand — and no defense industry.

This is why, before we talk about the companies that make planes, ships, and missiles, we have to understand how the government decides to buy stuff. This process of ‘defense procurement’ is the engine that drives the whole sector. Everything from a bullet to a battleship is procured through a government-run procedure.

That procedure has evolved over time, and it has shaped the fortunes of the entire industry.

The History: Phase by Phase

Phase 1 – Early years (post-independence to 1960s)

When India became independent in 1947, it inherited a network of British-era ordnance factories, which made some weapons for it. But these were limited in what they could do. In those early decades, India manufactured some defense items domestically – mostly small arms, ammunition, and simple equipment. But all the big and complex stuff (like fighter aircraft, warships, or heavy artillery) was imported.

This felt like a big vulnerability, and so, the government set up its own defense Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) — companies like Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd, Bharat Electronics Ltd, Mazagon Dock Shipbuilders and others — hoping to build a domestic industrial base.

Phase 2 – License Raj era (1970s–1990s)

For most of our early years, the whole of India’s economy was tightly controlled. Naturally, our defense industry was effectively a government monopoly. Only public sector entities were allowed to make weapons; private companies were outright prohibited from building big defense platforms.

This may have seemed like wise policy at the time, especially given the broader political climate that we were in. But it created a big problem: any weapon was practically made by just one entity, with little at stake, and no competition biting at its heels. Production was slow; innovation almost absent.

But that didn’t bring down the danger we faced in our immensely challenging neighbourhood. We needed weapons from somewhere. And so, India came to rely heavily on the Soviet Union for its defense needs, especially once the United States and Britain imposed arms embargoes in the mid-1960s (for example, during the 1965 war).

Over the 1970s and 1980s, a pattern was set: Indian ordinance factories and PSUs would produce basic equipment and ammunition. Most advanced weaponry, on the other hand — from MiG fighter planes to submarines — came from abroad, either directly under import contracts, or indirectly through license-production agreements.

The result? Through the late 20th century, India remained one of the world’s largest arms importers. Meanwhile, our domestic industry (all public-sector) stayed relatively limited in scope.

Phase 3 – Private enters, but it’s messy (early 2000s)

In 2001, for the first time, the Indian government opened up the defense manufacturing sector to private companies. Eventually, we even allowed limited foreign direct investment — up to 26%.

But here’s the catch: just because private firms were allowed to function didn’t mean they would actually get orders. The process to award defense contracts was still opaque and heavily favored our regular sources of arms. For a long time, in fact, the Ministry of Defence’s procurement rulebook wasn’t very friendly to private bidders — it lacked clear provisions for how a private company could compete for or execute large contracts.

The overhang of old corruption scandals played their role too. Public outcry reached its peak in the early 2000s, as the chaotic and corruption-prone defense procurement system became a political landmine. Notoriously, the 2001 “Tehelka” sting operation caught several officials — including a major political figure — on camera taking bribes in a fake arms deal. These scandals highlighted the need for more transparency and better rules in defense purchases.

This pressure led to the first comprehensive procurement rulebook: the Defence Procurement Procedure (DPP) 2002. Introduced in 2002, this marked the beginning of a structured approach to buying military equipment.

Procurement Evolves (2002 to 2020)

Since 2002, our defense procurement policy has been evolving steadily, with major updates every few years. Each iteration of the DPP tried to fix problems and encourage more private indegenous participation. Here’s a quick journey through the key milestones:

DPP 2006 – Offsets Introduced: By 2005-06, India added an offset policy to its purchases. In simple terms, offsets mean that if a foreign company sells weapons to India above a certain value, they must invest a portion of that contract value back into India’s defense industry (e.g. sourcing components or setting up facilities locally).

DPP 2008 & 2011 – Greater Role for Private Players: The 2008 update to the policy explicitly encouraged private sector involvement via categories like “Buy & Make (Indian)” — where we bought foreign weapons, but with production licensed to an Indian firm. The 2011 (and 2013) revisions went further in refining the preference for indigenous products. They established a clear pecking order for acquisitions – with buying Indian-made equipment at the top, and direct foreign purchases as the last resort.

DPP 2016 – Indigenization Push (IDDM): This became a watershed moment for “Make in India” in defense. The 2016 policy introduced a new highest-priority category called “Buy (Indian – IDDM)”, where IDDM stands for Indigenously Designed, Developed and Manufactured. The IDDM category was a big nod to Indian private innovators and start-ups – basically saying, “if you build a world-class product here at home, the armed forces would rather buy that than import.” This change aimed to spur local R&D and reduce the reliance on foreign tech.

DAP 2020 – New Name, New Ideas: Come 2020, the Defence Procurement Procedure was overhauled and renamed the Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP). The renaming wasn’t just cosmetic; DAP 2020 rolled in all the lessons of the past two decades. It laid out clearly defined procurement categories and made indigenous production the core theme.

So, under our current policy, we have a clear hierarchy in procurement categories. From highest to lowest priority, they are:

Buy (Indian-IDDM): Indigenously Designed, Developed and Manufactured in India – basically, these completely home-grown defense products.

Buy (Indian): Finished products from an Indian vendor – where the equipment is made in India, but not necessarily designed here.

Buy & Make (Indian): Initial purchase from an Indian company which has a tie-up with a foreign player – followed by licensed production in India.

Buy & Make (Global): Purchase from a foreign company, but partly manufactured in India. Here, the foreign vendor either sets up facilities or partners with an Indian firm to make parts of the system locally.

Buy (Global): Direct procurement of a product from foreign sources — this is the last resort if no suitable Indian option is available.

The key thread through all these evolving rules was self-reliance: pushing the system from buying 100% from a few friendly countries abroad to making as much as possible in India, with increasing roles for Indian industry (both public and private).

So, where do we stand now?

Today, India’s defense industry is far more diverse and dynamic than before. Private players finally have a seat at the table – they’re bidding for, and winning, defense contracts in a way that was unheard of a few decades ago. Companies like Larsen & Toubro, Tata Advanced Systems, Mahindra Defence, Bharat Forge, Adani Defence and others are now building everything from parts of fighter planes to artillery guns and naval ships.

In creating this domestic capacity, though, we’ve unlocked a much larger market. Although we’re still the world’s second biggest arms importer (only behind Ukraine, for obvious reasons), our defense exports are rising too. Indian-made equipment, like the BrahMos missile, or the Tejas fighter, is finding interest from foreign buyers – a point of national pride as well as business opportunity.

That said, the old guard hasn’t disappeared.

Our private defence sector is still in its infancy. The lion’s share of big projects — especially in aerospace and heavy platforms — still sits with government-run PSUs. In fact, defense public sector undertakings (like HAL, BEL, etc.), together with the ordnance factories, account for roughly 80% of India’s defense production by value, while private companies make up about 20%.

This isn’t something that our defence forces are necessarily happy with.

The government is actively trying to shift more of the workload to the private sector with policies like the import ban list on certain weapons, higher FDI limits, and the aforementioned procurement categories favoring local industry.

That wraps up our first defence deep dive. So far, we’ve set the stage with a historical look at how India buys its weapons – from the old days of import dependency to today’s Make-in-India push. Understanding this evolution gives us context for why certain defense firms are booming now. In the coming parts, we’ll get into the numbers that have investors excited: the defense budget (capex), company order books, production backlogs, and the surge in exports. That’s where the real growth story of defense stocks begins.

The big critical mineral mega-trends

The technologies of the future will be built on the back of weird rocks.

These rocks — a handful of minerals like lithium, cobalt or gallium — are going to be the raw materials for everything from the green energy transition, to AI data centers, to next-gen defence systems. They’re so important, in fact, that countries literally call them “critical minerals”. And the problem is: we don’t have enough of them, we don’t know how to get more fast enough, and most of what we do have flows through a single country — China.

While we’re no fortune tellers, here’s one thing we can confidently predict: in the years to come, you’re going to see the whole world fight to get their hands on these minerals.

We just came across a new report by the International Energy Agency — the Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025, and it’s a delight for economics nerds like us. Among other things, the report features a series of deep dives into some critical minerals mega-trends. And for those of you who aren’t inclined to go through its 300+ pages, we thought we’d take you through all the threads that matter the most.

Let’s dive in.

How can the rest of the world catch up?

If there’s one thing you already know about critical minerals, it’s that a handful of countries — China, more often than not — control everything.

This is, sadly, just how economics works. The tighter you control a supply chain, the easier it is to control. Once you have a foothold in these industries, all sorts of tailwinds start working in your favour. You create network effects around yourself, you master the processes involved, and the scale you’re operating at pushes down your costs.

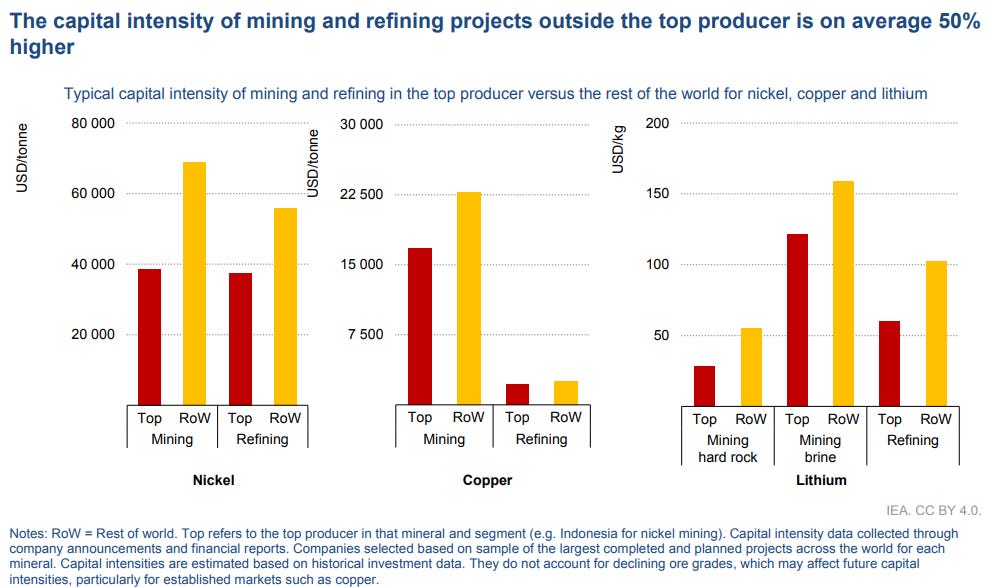

For everyone else, though, challenging this dominance can be an uphill battle. You need more capital to get started, and your operations cost much more. By IEA’s estimates, in fact, if you’re challenging an incumbent, you need 50% more capital than they do.

What makes things worse is that, in the market for minerals, you have no pricing power. These are all commodities markets: prices are purely a question of global demand and supply. Whenever global prices fall, it becomes terribly difficult to stay commercially viable.

This makes it difficult for alternative sources of these minerals to come up. So, what do you do to get around these issues?

The first answer everyone lands on, here, is for governments to give cheap financing to critical mineral projects. But that isn’t enough: in such a concentrated market, you should expect extreme risks — including market manipulation by the incumbents. Financial might alone might not help you tide over them.

This is why the IEA points towards market-based mechanisms instead. If it’s hard to compete with incumbents on costs alone, you need to find a way to take prices out of the equation — allowing new entities to charge higher prices than their established competitors. Here’s what that can look like:

Certification: Countries can invest in creating a certification process — if a new entrant does better on environmental or social grounds, for instance, they should have a way of getting this verified. Take Nickel for instance: according to the IEA, 80% of all Nickel businesses outside the world’s top three Nickel-producing countries, just cannot survive at current price levels. This is, to a great extent, because the world’s top producers have extremely carbon-intensive processes. If new producers can charge a ‘green premium’, the report believes that could add ~80% more supply from countries outside the top three.

Price support: Countries could try introducing ‘cap-and-floor’ models: where governments agree to subsidise producers when prices fall below a certain floor, in exchange for a promise that producers will pay the government back if prices go above a ‘cap’. This makes it easier for businesses to insure themselves against commodity downswings. This is similar to what governments already do for green energy projects.

Purchase commitments: Governments could promise producers that they’ll buy a certain volume of their produce, as long as they meet some sort of minimum standard. This gives producers some certainty that they can sell their product, giving them more peace of mind while making investments.

These are tricky tools to use, though, with major trade-offs. Economics can be slippery; by intervening in markets, you can end up creating all kinds of distortions and weirdness. Any country that attempts these mechanisms must pay a lot of attention to how they design them.

What follows NMC?

A couple of days ago, we covered batteries — and we’d touched on how the world’s moving from Nickel-Manganese-Cobalt (or ‘NMC’) batteries to newer alternatives. This was a dramatic shift: in 2020, 90% of the global EV market ran on NMC batteries. But then, nickel and cobalt prices went through the roof. Manufacturers scrambled to find alternatives — and they succeeded.

Lithium-iron-phosphate, or ‘LFP’ batteries, in particular, jumped in to fill the gap. In a few short years, they’ve come to power almost half the world’s new EVs. Other chemistries are coming up too — such as sodium-ion batteries, that completely side-step any need for Lithium.

Behind this, there’s a fundamental frame that will help you understand how this space is evolving: if you want to make batteries, you’re necessarily boxed in by the ingredients you have access to. You simply can’t wish away this constraint. The battery technology that wins, in the future, is the one with the most easily available critical minerals.

This should tell you two things:

One, if you’re trying to figure out where the battery industry goes, it isn’t enough to just look at a single supply chain. Instead, right now, there are many different supply chains that are competing to win over the industry — and the one that snaps into place the fastest is the one that will dominate the future.

Two, different countries are positioned differently in each supply chain. Given that we are entering an era of ‘weaponised interdependence,’ if you can control the winning supply chain, you could control the future trajectory of the world.

Take LFP batteries. China may dominate NMC battery supplies, but it practically owns the entire supply chain for LFP batteries. It’s frankly the only player; the rest of the world is no competition at all. They have an incredible pricing advantage too — because China’s such a manufacturing giant, they can get their hands on many different ingredients for those batteries, at unbeatable prices. And China is trying to entrench its dominance — it is extremely secretive about the technology you need to make LFP batteries. That makes it much harder to diversify away from China.

The picture is more complex for sodium-ion batteries. These aren’t energy-rich enough to power higher end EVs, but could take up a serious chunk of the lower end models: like low range EVs, or two/three wheelers. China has a much weaker hold on this supply chain. It still dominates the final production of these batteries, but the materials, at least, can be sourced from a wider range of places. It’s harder to lock up this supply chain as well: it simply relies on far fewer critical minerals.

The batteries of tomorrow could take many different shapes. But one thing is inescapable: most supply chains, today, pass through China: both for existing technologies, like LFPs, and for future technologies, like solid-state batteries. If we fail to diversify away, it will dictate the fate of the rest of the world.

Scaling up supply-side innovation

Fundamentally, our ability to create the technologies of the future is limited by the critical minerals we have access to. Our best bet is to innovate our way through this bottleneck. Usually, this pushes one to think about “demand-side innovations”: or ways that we cut down the amount of critical minerals we need. For instance, we’ve cut down how much silicon we need to make solar cells by 55% over the last decade.

The IEA report highlights the other side of the equation, however: supply-side innovations. It points to how we can produce these minerals, creating technology that helps us get more of these critical minerals, for cheaper. The report spotlights many big leaps we’ve made in this direction — and while we can’t go through them all, here are just a few that caught our eye:

Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE): Most of the world’s Lithium doesn’t sit neatly in underground mines. It’s found in salty lakes, in low concentrations: and so far, the only way of extracting any was to dry those lakes up and trying to isolate their Lithium salts. But that isn’t easy, and reducing entire lakes can leave deep environmental scars. We’ve now found our way around this challenge: we pump out lake water, run it through special media that absorbs all the Lithium, and then pump the rest back into the lake. 10% of global Lithium now comes from this new technology.

Low-Carbon Synthetic Graphite: Batteries need graphite for fast charging. But making graphite is a dirty business: you need to blast pet coke with heat as high as 3,000 °C. We currently do that by burning lots of coal, polluting the very environment we’re trying to save. But some start-ups have found smarter ways to do this: using new ‘induction’ and “inside-out” graphitisation furnaces. To over-simplify things terribly, these new technologies are a little like moving from heating food on your gas stove to microwaving it. With them, the energy you need to make graphite is halved.

Re-mining tailings: Mines are extremely wasteful — generally, for every kilo of a mineral you can extract, you have to throw away tens of kilos of waste. This accumulates in giant lakes filled with sludge. called “tailings” — and these are an environmental catastrophe waiting to happen. But we’re now developing new technology to mine these tailings as well — helping us come up with even better mineral grades than you get from the mines themselves.

This space is filled with many more fascinating new developments. And that will only accelerate: artificial intelligence, for instance, is already helping companies get much, much smarter with where to drill their mines.

But there are also serious barriers that we’re running into. For one, China’s dominance is, once again, a problem. It has a lot of critical intellectual property that we need to improve our processes, but it’s blocking the rest of the world from accessing it. Others must re-invent the wheel to get anywhere close to its prowess.

Beyond that, however, there are all the regular problems that come with bringing new innovations to life. New technologies are expensive at first, and need a lot of capital before they can make a serious dent. Regulation and red-tape make it even harder to push promising new technology out. If we’re hopeful about innovating our way into a better future, these are bottlenecks that we need to attack.

The big risks on the horizon

These are immediate trends to keep an eye on. But, zooming out, the report looks at various big picture risks that are looming around the horizon. Here are some of the important ones to look out for:

New industries will bring new demand: Thus far, the world has looked at critical minerals, by-and-large, as inputs into our looming green transition. But that’s just one reason we need them. There are at least three major new industries that will suck up critical minerals at a pace we haven’t seen so far: artificial intelligence, robotics, and aerospace. We aren’t just trying to secure more critical minerals to create climate-friendly technology — we’re looking to fuel a much wider technological explosion.

Our supply chains are small, opaque and brittle: Many critical minerals trade in markets that are relatively small and opaque. Production is limited to just a few entities, and there’s very little depth beyond them. When problems arise, markets like this can suddenly get choked. Slight shifts in supply or demand can trigger huge price swings, which nobody might see coming. Setting up more capacity, on the other hand, takes a lot of time and money — making the system slow to adjust. Expect terrible tail risks that will arise suddenly, and take time to resolve.

Concentration risk: In more than 40% of the strategic minerals the IEA looked at, a single country controls half of the world’s output. Refining is even worse: China practically controls every mineral, with an average market share of 70% in each. For some — like gallium, graphite, manganese and rare earths — it controls almost all of the world’s production. This is a big risk: one policy tweak, export curb or supply chain failure could literally cut the entire world off these minerals.

A failure has huge consequences: The subtext behind all these risks is a simple fact: some of the world’s most important technologies — from EVs, to chips, to defence systems — rely on these supply chains. With such high stakes, there’s no margin for error. If supply is cut, the results could be catastrophic. They’d have a direct outcome on GDP, industrial competitiveness and even national security.

Tidbits

Foxconn Commits $1.5 Billion to India Unit Amid Apple’s Supply Chain Shift

Source: Reuters

Foxconn has announced a $1.541 billion investment into its India unit, Yuzhan Technology India, through its Singapore-based subsidiary. The investment will be made via the purchase of 12.77 billion shares at ₹10 each, according to a regulatory filing. The move comes as Apple continues to diversify its manufacturing footprint beyond China. In March 2024, Apple exported 600 tons of iPhones worth $2 billion from India to the United States, highlighting India’s growing role in its global supply chain. The new capital is expected to support Foxconn’s expansion in Tamil Nadu, a key electronics manufacturing hub. While the broader market impact remains to be seen, the deal aligns with India's ongoing push to become a high-tech manufacturing destination.

Diageo India Q4FY25 PAT Rises 17%, Full-Year Profit Declines 12%

Source: Business Line

United Spirits Ltd, the Indian arm of Diageo, reported a 17% year-on-year increase in standalone profit after tax (PAT) to ₹451 crore for Q4FY25. Net Sales Value (NSV) for the quarter stood at ₹2,946 crore, marking a 10.5% YoY growth. However, for the full year FY25, PAT increased to ₹1,558 crore from ₹1,312 crore in the previous fiscal. Gross revenue for the year rose slightly to ₹6,549 crore from ₹6,394 crore. The Popular segment grew 1.1%. The company attributed the quarterly growth to a resilient performance in key trademarks and its re-entry into the Andhra Pradesh market. CEO Praveen Someshwar noted that despite a challenging demand environment, the company achieved 13.2% NSV growth in P&A for the quarter and maintained momentum toward its medium-term EBITDA guidance.

SBI Gets Board Nod to Raise $3 Billion via Foreign Market in FY26

Source: Business Standard

The State Bank of India (SBI) has secured board approval to raise up to $3 billion through long-term debt instruments in FY26. The funds will be mobilised in one or more tranches via public offers or private placements of senior unsecured notes denominated in USD or other major foreign currencies. SBI’s international business saw notable growth in FY25, with gross overseas advances rising 14.84% YoY to ₹6.19 trillion, and foreign deposit base increasing 12.3% to ₹2.15 trillion. The bank’s global credit portfolio is broadly balanced across external commercial borrowings, local overseas credit, and trade finance, each contributing roughly one-third to the total. SBI’s international operations span the US, Singapore, GIFT City, West Asia, and East Asia.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Pranav.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Introducing “What the hell is happening?”

In an era where everything seems to be breaking simultaneously—geopolitics, economics, climate systems, social norms—this new tried to make sense of the present.

"What the hell is happening?" is deliberately messy, more permanent draft than polished product. Each edition examines the collision of mega-trends shaping our world: from the stupidity of trade wars and the weaponization of interdependence, to great power competition and planetary-scale challenges we're barely equipped to comprehend.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉