Back to Trade Wars?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Welcome to a new world order

Making Nuclear Great Again

Welcome to a new world order

So… Donald Trump just nuked the global economy.

We’ve been waiting on these for a while. A couple of days ago, we wrote here about how we had no idea what Trump’s latest tariffs would look like. Well, we have a bit of a sense now. And they’re worse than we thought:

For one, starting this Saturday, every single good that enters the United States will be hit by a 10% tariff.

Then, starting next Wednesday, extra tariffs will be applied to 57 countries. India is one of them — we’re being hit by a 27% country-specific tariff. Nobody seems to know for sure, but from what we can tell, these are all on top of the flat 10% tariff.

If there’s a tiny bit of respite, it’s this: some of the stuff they’d already slapped tariffs on are exempt from this newest order. So the tariffs on steel, aluminium, pharmaceuticals etc. don’t get much worse. But that’s not true of everything. In general, all the older American tariffs still stick; he’s only added new ones on top.

Basically, mid-next week, our exports will probably be 37% more expensive for American consumers than they are today. That’ll be true of exports from all across the world — Chinese goods will be 44% more expensive, Vietnamese goods will be 56% more expensive, and so on.

Don’t make the mistake of writing this off as a non-event, or imagining that all those exports will just find their way to some other country. The United States is the world’s largest importer of goods. Its total imports for 2024 added up to $3.3 trillion. That is, in case you missed it, approximately the size of India’s entire economy. American imports make for more than 3% of the world’s GDP.

So, in the space of a week, an India-sized chunk of the world economy — and the source of livelihood for hundreds of millions of people worldwide — will suddenly become much harder to reach. That doesn’t just change the business math for a handful of exporters; in the coming months, expect these to unleash a series of chain reactions which ultimately touch everything.

What does the world look like when we emerge on the other side of this? We would be dishonest if we even pretended to know — because we don’t. At all. We aren’t journalists or economists; we’re nerds that like learning about the world. This is a huge deal, and more than that, it’s a complex one. We’re piecing it all together ourselves.

Today, we’re going to try and round up everything we’ve heard from smart people from all over the world. If this gets a little long or rambling, forgive us? Consider it a special indulgence for our 200th edition. 🙂

Why us? Why 27!?

Trump’s big complaint against the rest of the world, India included, is that we’re all “ripping America off” in some fashion. In his theatrical tariff announcement, he carried a huge board listing all the tariffs other countries placed on the United States — and what they would charge those countries in response.

India was charging the United States a tariff of 52%, he claimed. In return he was charging us a discounted rate of 26%. (Incidentally, the White House website lists this as 27%, so the actual rate isn’t even clear. But we’ll leave that be; clerical mistakes are the least of anyone’s concerns these days.)

Put that way, it almost sounds generous. Only, this is completely fake. We don’t charge tariffs anywhere close to 52% on American goods.

America knows this. In the lead up to Trump’s latest salvo, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) had released a 400-page report, listing all the United States’ government’s actual complaints against other countries. According to the USTR, India’s effective tariff rate was 17%.

In fact, even the actual text of Trump’s own executive order lists our tariff rate at 17%.

Which begs the question: where in the world is that 52% figure coming from? If you look at the fine-print in Trump’s board, he’s lumping together “currency manipulation” and “trade barriers” in the tariff rate. Some of that’s true: we’ve often talked about India’s many regulatory barriers to business. Only yesterday, we brought up India’s import quotas for met coke.

But 52%? What math got them there? How do they even reduce things like licensing requirements into hard numbers? We don’t know. All we know is that, by next Wednesday, America’s tariff rate will be much higher than anything we’ve charged since the License Raj.

By the way, this is not just a problem that’s limited to us. Others have complaints too:

In fact, there’s some speculation that they didn’t even try figuring out countries’ tariff rates: they instead did some lazy back-of-the-napkin math: dividing the trade deficits with a country by their overall imports from it — and simply labelled it the country’s “tariff rate”. If you’re wondering, that’s complete hogwash.

Is there a steel-man case here?

But let’s keep the rates aside. Let’s try giving Trump some benefit of the doubt, at least as a general matter. Is there something here — some well considered rationale, behind all the bluster? Is India just the unfortunate victim of otherwise sensible economic policy?

Well, in some sense, there are people who are thinking hard on these lines. These tariffs mark a collective disillusionment with mainstream trade economics. There’s a sense, across America, that sticking to the international trade system has left it cheated, and has allowed others to progress at its expense. For a well-articulated version of this argument, you can check out this link. That’s why Trump hates “trade deficits” so much — he sees them as other countries pulling the wool before American eyes. In his logic, every time America imports something, that’s one good that an American business is not producing. And so, if America imports much more than it exports, all of that is lost business for Americans.

By itself, this isn’t a completely unfounded view. In fact, economists like Michael Pettis believe that countries like China only became export superpowers by crushing the ability of their own populations to buy things. In this telling, such countries functionally forced a country like America into a trade deficit. We won’t get into why here — that’s a story for another day — but let’s take this argument at face value.

All Trump is trying to do, then, is to reverse these deficits.

We’re sceptical, though, for many reasons:

A general trade deficit could conceivably be an economic problem worth fixing. If, overall, your country imports more than it exports, you might consider the situation unsustainable. Controlling every single bilateral trade deficit, on the other hand, makes no sense. Some countries simply supply things you really need, and there’s no point cutting them out. That would be a little like refusing to get a haircut because your barber doesn’t buy anything from you.

Tariffs don’t do anything automatically — the real question is how they’re applied. Economists that see American deficits as a problem do so because there are deep, structural issues that are hampering American manufacturing and discouraging exports. And structural problems require structural solutions. Haphazard tariff rates only address symptoms, not the actual issues underneath. Here’s Michael Pettis himself, coming out against the tariffs:

These tariffs, despite the branding around them, are not “reciprocal”. Other countries pick-and-choose their tariffs — they individually select different tariff rates for more than 13,000 items. For instance, while India has triple-digit tariffs on some agricultural products, there are other goods — like some machinery — that essentially can come in duty free. In contrast, Trump’s new tariffs hit everything all at once.

This lack of precision creates problems for America itself, because there are some products that American businesses will never make. Consider, for instance, that America gets most of its rare earth minerals from China, which are central to manufacturing high tech goods. Suddenly, those will now be tariffed. Similarly, no matter how high the tariff rate is, Americans can’t grow chocolate on their own soil. An American chocolatier has no option but to import. In these cases, the trade deficits remain, but only get more expensive.

Finally, a lot of these “trade deficits” America’s talking about are goods trade deficits. That’s only one part of the picture. For instance, a huge chunk of American exports — worth over $700 billion — are digital. Think about it: in a sense, we’ve paid America while writing this story, by using everything from AI to premium social media subscriptions. If you ignore these, things will naturally look a lot less fair than they are.

What does this do to the world?

One of the best pieces of advice we’ve heard, when it comes to the new tariffs, is to chop down your time horizon for how you’re planning about the future. Face it: when something like this happens, you can’t look a few months into the future. There’s too much that’s up in the air. This is one of those times when you take the world in one day at a time.

These newest tariffs mark a return to the 1800s. In one shot, America unwound a century of progress in economic thought. Frankly, analysts are struggling to even draw charts to represent this point in time, because of how quickly America’s tariff rate has jumped. That line can’t go up fast enough.

Sidenote: Some of them are even having fun with this fact:

In the near term, that could spark economic turmoil, or even a recession.

If you don’t trust JP Morgan, Polymarket is tilting towards a US recession as well. And if you remember, Polymarket had predicted Trump’s electoral win when nobody else did:

But things hardly stop at a couple of bad quarters. At the moment, there’s a whole mountain of questions that remain open:

For one, we know that such huge tariffs will probably cut down the amount of trade happening in the world. And because of that, the world’s GDP will take a hit. By how much, though? We’re not sure. In a worst case scenario, this could trigger a crisis like the one in 2008 — which pulled down the GDP of emerging markets like India by 3-5% across half a decade.

Two, we still don’t know how kindly the world will take to America blocking them out of their economy and how they’ll try coping with the fall-out. They could retaliate with their tariffs. They could respond with manufacturing subsidies. They could let the value of their currencies fall. Each country will make its own choices, and all of those choices will have knock-on effects of their own.

Three, we don’t exactly know how relative tariff rates could play out. Consider, for instance, that even though we have huge tariffs against us, one of our main rivals for low-cost manufacturing — Vietnam — has been hit by tariffs that are almost 20% higher. Does that mean we actually gain from these tariffs? We aren’t sure. There are simply too many variables at play.

Four, with all this uncertainty, we don’t know how consumers, companies and investors behave in these times. Right now, it’s really hard to make predictions for a few months into the future. When that happens, people hesitate to make long-term decisions — like decisions on foreign investment, or real estate purchases. That, in turn, has its own unpredictable effects on the economy.

Five, looking out longer, we have absolutely no sense of how the global economy will adjust to having its fulcrum being ripped out. This is impossible to model — the range of possibilities is too enormous. The rest of the world could coordinate much more, perhaps shaping a global system with China at its centre. Equally, these tariffs could unleash a wave of dumping across the world, which pushes countries everywhere to act far more aggressively with each other. Frankly, anything could happen.

All of this is to say, there’s no easy answer to what these tariffs do.

Inflation is just plain math

As we said the last time we covered this, the long-term success of these tariffs boils down to how ordinary Americans react to them. If these tariffs turn out to be hugely unpopular — if Americans think they’ve caused serious damage to their lives, that cuts down the breathing room Trump has for his trade policy.

That’s why one of the biggest questions around these tariffs is whether they’ll be inflationary.

The short answer? Yes. In the space of a single day, inflation probably went up 1.3%.

But let’s get deeper into it.

Some of it is simple math. By a quick calculation, if trade remains exactly the same as it is today, the newest tariffs would cost $500 billion (of course, that number will fall because people will buy less, but we won’t go into that here). All that money has to come from somewhere. Unless all exporters to the United States have extremely deep margins (they don’t), there’s no way they’ll pay out of their pockets — it would make more sense to not sell at all. Which is to say, at least some of that cost will be passed on to customers.

How much? We don’t know. To be honest, we’ve never seen such huge tariff hikes before, which is why there’s nothing to compare these to. But the research points towards pain. See, no company wants to raise prices alone. When policies hit specific companies (or even segments), companies sometimes stomach the losses. But huge, system-wide shocks like this give companies the cover they need to ramp up prices. That’s why economy-wide issues cause far more inflation than issues that individual companies face. If you remember the uncontrollable inflation towards the later end of the COVID-19 pandemic, you’ll see what we mean.

Of course, that’s not to say that the entirety of these tariffs will be passed on to American customers. If customers are simply unwilling to pay those high prices, some companies may be forced to take a hit to their margins. But you can’t take that for granted. Whether that happens is a complex economic question.

Consider, for instance, that major smartphone sellers in America import their products from elsewhere. The two industry leaders — Apple and Samsung — both make their products abroad. That means that there’s no real non-tariffed alternative to their phones on the market. Anyone that buys a phone has to buy a tariffed phone. Why would either company cut their own margins?

Trump’s own administration knows this. Consider how they’ve changed their tune recently. Last year, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent was out assuring everyone that tariffs were too wild an idea to actually be put into action. In his words, “The tariff gun will always be loaded and on the table but rarely discharged.”

Now, he’s trying to comfort people that tariffs won’t do much. As he recently told the Economic Club of New York, “Access to cheap goods is not the essence of the American dream.” Reading between the lines, to us, this looks like the administration is trying to get people to brace themselves for higher prices, now that tariffs are a reality.

The bottom line

That’s the only real hope we have, through this whole mess. If we know anything about how economies work, then what Trump has just done is deeply irresponsible. That remains true even if you buy his broader argument that America needs more manufacturing jobs. He’s trying to uproot a system that has been built over a century. And the only people who can tell him to stop are Americans themselves.

Will they? And will he listen if they do? Frankly, we don’t know. All we can say is that we’re staring at something unprecedented. We’re bang in the middle of history being made. At times like this, there are no easy answers.

Making Nuclear Great Again

NTPC, India's largest power utility, is changing track — it’s trying something really big, in fact. It’s inviting global companies to help it build 15 GW of nuclear power capacity. To put that in perspective, India's current installed nuclear capacity is just 8 GW, so we’re talking about almost tripling what we currently have.

Zoom out a bit, and the scale gets even more staggering. India is eyeing a target of 100 GW of nuclear capacity by 2047. That is crazy ambitious, especially given where we’re starting from.

This is part of something bigger. India has this mega goal of achieving 500 GW of non-fossil fuel energy by 2030. While everyone loves talking about solar and wind — after all, they're the ‘in thing’ right now — there's a catch. The sun doesn't shine all the time, and the wind doesn't always blow. This intermittency is a huge issue.

As Bill Gates neatly summed it up: "Nuclear energy, if we do it right, can be the answer to our energy prayers. It's the only carbon-free energy source we have that can deliver power day and night, through every season, almost anywhere on Earth."

There's also the fact that they require far fewer resources. One tonne of natural uranium can produce as much electricity as 16,000 tonnes of coal, making it one of the most energy-dense fuels on the planet. Meanwhile, according to a study by the US Department of Energy, nuclear plants require 360x less land than solar farms to produce the same amount of electricity.

All of this is why nuclear can’t be brushed aside.

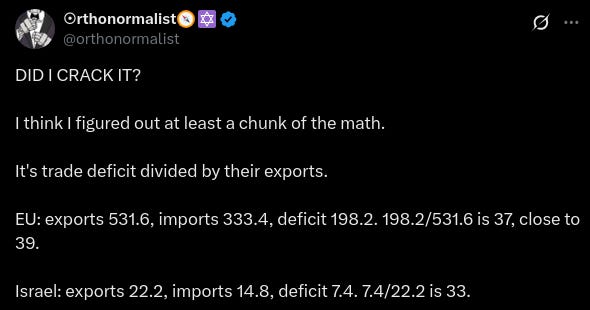

Countries like France, Slovakia, and Ukraine get over half of their electricity from nuclear energy. India’s number? Barely scraping 3%. Sure, it’s not entirely fair to compare ourselves to those countries — we’ve got unique challenges and a lot of historical baggage. But it’s still worth thinking about what we can do to improve that number.

That’s why, today, we’re going to talk about India’s nuclear ambitions. We'll dive into recent developments, the geopolitical dynamics, the India-US nuclear deals, regulatory frameworks, and exciting new tech like Small Modular Reactors (SMRs).

Think of this as your crash course on all things nuclear energy in India—at a time when things are finally looking up, maybe for the first time since 2008, when India signed that landmark deal with the US.

What’s up with nuclear?

Alright, before we jump into what’s happening right now, let’s first take a quick detour into the basics: what is nuclear energy, anyway?

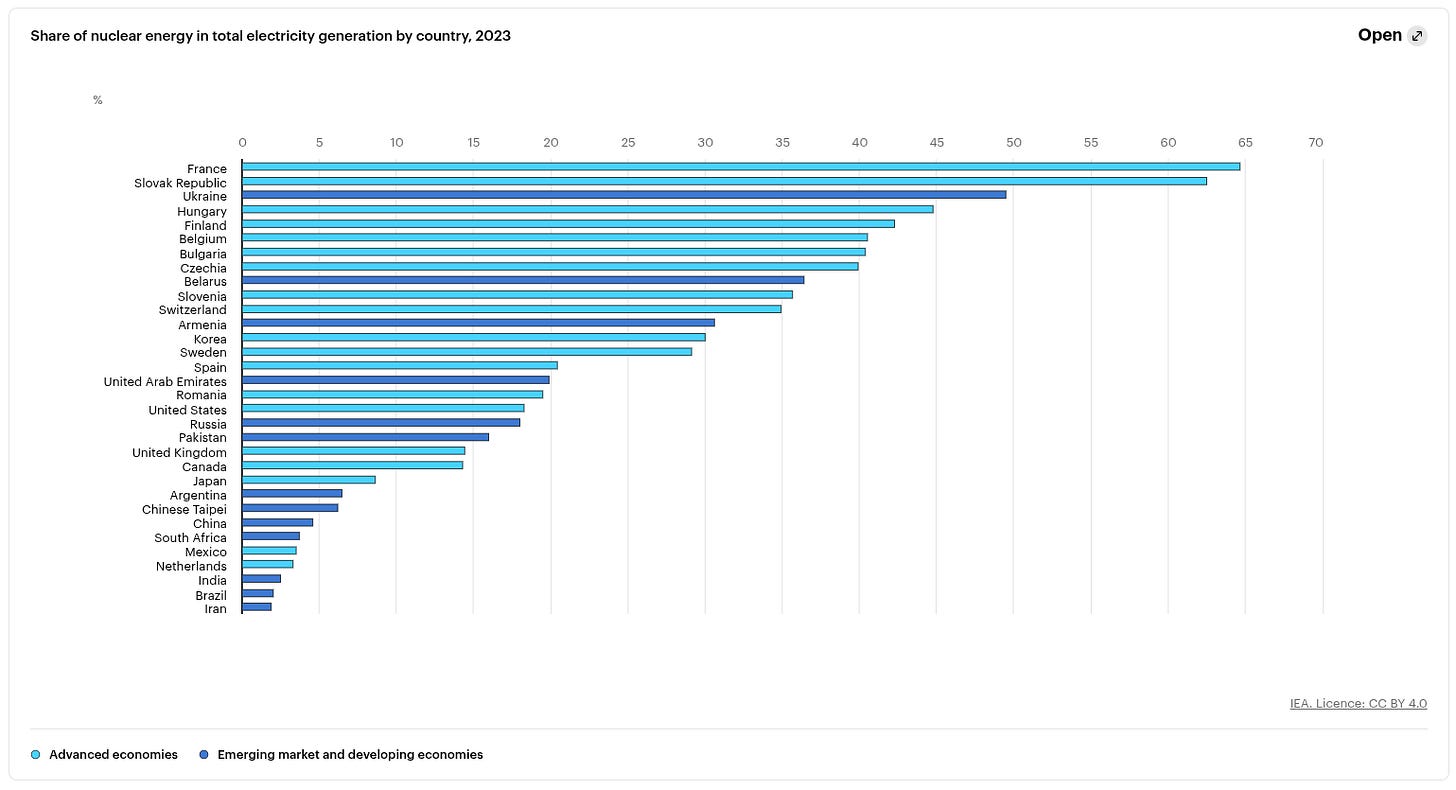

Most nuclear energy comes from splitting atoms — in a process known as nuclear fission. That creates a lot of energy; energy you can use for everything from bombing your enemies to running your cities. Today, we’re going to focus only on the peaceful side — specifically, electricity generation.

Here's how it works in super simple terms: in a nuclear power plant, atoms of some radioactive material (usually uranium) are split inside a reactor. Every time you do that, it releases a lot of heat. That heat turns water into steam. That steam spins a turbine, which powers a generator. And voila—you get electricity! Now, there are different types of nuclear reactors, and their specifics can vary. But the basic principle remains the same: nuclear fission.

If you can imagine how small an atom is, and how complex it is to split it safely, you know how incredibly hard any of this is to achieve. Which is why this process relies heavily on technology, know-how, and a steady supply of nuclear fuel.

That’s where India’s story gets complicated.

Back in 1974, India conducted its first nuclear test — Smiling Buddha — using material that was actually shared with us for peaceful purposes. That test didn’t go down well internationally. In response, a bunch of countries formed the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) to prevent this kind of tech from being used for weapons. India, having crossed that line, got cut off.

That didn’t stop the pressure, though. The global community wanted India to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which only officially recognizes five countries as nuclear weapon states. If we joined in, we would have to give up the ability to have nuclear weapons. And so, India said no—mainly because of real threats from China and Pakistan.

Then came the second round of nuclear tests in 1998 at Pokhran. That made things worse. The world doubled down on isolating India, and cutting it off nuclear supply chains of any sort.

With no access to foreign uranium or reactor tech, India had to go solo. Problem is, the Uranium we find in India is low in both quality and density. What this means is that we could only extract so much energy from it. Therefore our reactors ran at very low capacity — what’s called a poor ‘plant load factor’ (PLF). Our PLF was at 40% due to severe fuel shortages, meaning our plants were running at 40% of its actual capacity.

Moreover, we found it impossible to improve. All of this is extremely tech-heavy, and we didn’t have much global support to push our program through. We had to choose between being a nuclear power and using nuclear power, and we made our choice.

Then, in 2008, came a sliver of hope: the India-US nuclear deal, or the "123 Agreement." This was a big win. Even though India still hadn’t signed the NPT, the US agreed to let us access nuclear technology and fuel for civilian use. That meant we could now import uranium. We started importing it from Kazakhstan, Russia and Canada.

This deal helped raise our reactor performance. Our PLF suddenly shot up to 90%.

But here’s the catch: while we could now get fuel, in 2010, things started to fall apart all over again. Our nuclear program wound down, and once again, we struggled to set up new nuclear plants with foreign partners. The roadblock? A new, and very controversial clause in our Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act.

This new clause said that if anything went wrong at a plant, the supplier—not just the operator—could be held liable. Globally, this is not how it works. Suppliers usually walk away once they deliver equipment. But with this law, they would constantly be worried about legal action if anything ever went wrong, even years after booking a sale. This law spooked everyone. Foreign companies, including American giants like Westinghouse and GE, just didn’t want to take the risk of setting up shop in India.

We actually wrote about this in The Daily Brief: India’s liability law made sure that, despite a green light from the US, no foreign player was willing to enter India’s nuclear energy space.

And so, even though we signed the 123 deal all the way back in 2008, things didn’t take off. We got access to uranium and some diplomatic brownie points. But the real stuff — like building new nuclear plants and getting foreign players involved — hit a wall.

Why is 2025 so special for nuclear power in India?

And that brings us to today. After years of nuclear stagnation, things finally seem to be moving again.

First, the government indicated its willingness to rethink its stance on supplier liability. In the 2025 Union Budget, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said the government plans to amend the law. Committees have already been set up to explore changes to the Atomic Energy Act and the liability law, with members from across government departments, ministries and think tanks. While there's no fixed timeline, the intent is clear: ease up the liability rules to finally welcome foreign suppliers.

That’s not all. The government also announced a ₹20,000 crore commitment to nuclear energy, with a special push for Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). There’s even a plan to deploy five SMRs by 2033, including a homegrown version called the Bharat SMR (BSMR).

Two things set SMRs apart from regular, bulky reactors:

One, they’re small: Compared to traditional reactors, SMRs have lower capacity (typically under 300 MW)

Two, they’re modular: They’re factory-assembled and transported to the site, which makes them quicker and cheaper to install.

SMRs are safer by design, can be scaled up easily, and are perfect for remote locations or to supplement grids. Unlike older large-scale reactors, SMRs have passive safety features and need less space, making them more manageable.

And after rolling up its sleeves on SMRs, India got the United States on its side.

In a recent breakthrough, the U.S. Department of Energy allowed Holtec International to share SMR tech with three Indian private companies: Holtec Asia, L&T, and Tata Consulting Engineers. That a big deal — countries guard most nuclear technology closely, and in sharing it, America has shown a lot of goodwill. There are limits, of course — these companies must stick to peaceful use only, report quarterly to the U.S., and can’t pass on the tech without prior approval.

Now, notably, government entities like NTPC or NPCIL have been left out of these approvals. Why? Well, India hasn’t given non-proliferation assurances yet for these agencies. It hasn’t yet promised that these entities wouldn’t repurpose all that technology to make weapons. Naturally, the U.S. is a bit skittish, thanks to India’s 1974 test using material meant for peaceful purposes. So for now, only private players are in the game.

The silver lining? SMRs have minimal weaponization risk. They’re safer, smaller, and tightly monitored. Globally, only Russia and China have operational SMRs today. If all goes well, India might join that list by 2033.

And that brings us back to NTPC—the government’s big player in power. NTPC has invited global expressions of interest for 15 GW worth of nuclear capacity. But because it's a government entity, U.S. firms likely won’t participate unless the assurance issue is resolved. That leaves the door open for Russian or other non-U.S. players.

Whichever way this goes, a sector that’s been stuck in slow motion for years is finally showing signs of movement. Watch this space for more. None of this will happen quickly. Nuclear energy isn’t like solar — it doesn’t explode overnight. Plants take years to build. Laws take forever to change. Bureaucracy moves like molasses.

But progress is progress. And we’ll be here, watching, explaining, and simplifying things as they unfold.

Tidbits

Indian companies raised ₹58,000 crore from overseas capital markets in FY25, marking a 28.5% increase from ₹45,007 crore in FY24, according to data from Prime Database. The figure also represents a significant rise from ₹15,592 crore mobilized in FY23. Leading the fundraising activity was Exim Bank with ₹8,643.68 crore, followed by State Bank of India with ₹5,049 crore and Shriram Finance with ₹4,189.44 crore. Other major issuers included REC at ₹4,183 crore and Piramal Capital and Housing Finance at ₹3,771 crore. The increase has been attributed to a fall in hedging costs, strong global demand for Indian high-yield papers, and India’s growing presence in global bond indices. The total amount raised, however, remains below FY22’s ₹99,000 crore.

In a fresh order related to the NSE co-location case, SEBI has imposed a ₹5.2 crore penalty on OPG Securities and its three directors. The action follows a prior SAT ruling that had set aside SEBI’s earlier disgorgement order of ₹15.57 crore. SEBI has now recalculated the penalty based on the SAT’s directions. In a separate development earlier this year, SEBI had revised the disgorgement amount to ₹85 crore while dropping charges against NSE and its former officials due to lack of evidence. SEBI also noted that one of the directors failed to cooperate during the investigation, which was considered while determining the penalty.

Tata Power is set to expand its coal-based capacity for the first time since 2019 by adding 1,600 MW to its existing 1,980 MW Prayagraj Power Generation plant in Uttar Pradesh. This move comes as India’s renewable energy sector faces hurdles such as weak tender demand, land acquisition issues, and over 40 GW of unsigned clean energy sale agreements. Despite India adding nearly 28 GW of solar and wind capacity in 2024, fossil fuels contributed over two-thirds of the increase in power generation that year. The government also plans to increase coal-fired capacity by 80 GW by 2031-32. Tata Power currently operates about 8.9 GW of coal-based capacity across six states and aims to scale its clean energy portfolio from 6.7 GW to over 20 GW by 2030 with a planned investment of $9 billion.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Kashish

📚Join our book club

We've recently started a book club where we meet each week in Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you'd like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

As a finance student, the content is really useful and relatable.

Congrats on the 200th edition