Another robust quarter for India’s midcap IT firms

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Another robust quarter for India’s midcap IT firms

The dollar comes in waves

Another robust quarter for India’s midcap IT firms

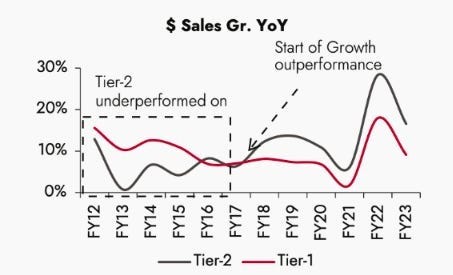

A few months ago, we wrote about why India’s midcap IT firms have been outperforming their larger cousins.

See, large-cap IT companies have been way too slow to adapt to the new paradigm. Meanwhile, smaller mid-cap firms don’t bear the baggage of their larger peers, and are far more nimble. In comparison to Indian IT’s low-value body-shopping work, midcap IT firms operate in higher-value activities, making meaningful additions to software engineering. Their domain specialization and openness to AI also help them.

Then, it’s no secret why they’ve done so much better than large-cap IT over the past 8 years. And this thesis continues to hold up this quarter.

But the timing of these results was a little awkward. Not long after quarterly results were out, the stocks of US software companies, Big Tech firms, and Indian IT companies, all fell.

We can’t truly say for sure why. Some suggest that the culprit is AI (particularly Claude), although there are certainly other factors at play. Either way, the stock prices of both large-cap IT (like TCS and Infosys) and midcap IT (like Persistent Systems, Coforge) fell.

However, one quarter’s selloff doesn’t determine who wins the marathon. And if you look at what these three mid-caps actually reported, the picture is more nuanced. So far, they’re holding their own in the AI race fairly well, while also taking market share from larger competitors.

With that, let’s dive into the results of Persistent Systems, Coforge, and Mphasis. We recommend reading our previous primer on midcap IT for better context.

The numbers

Let’s start with the headline figures.

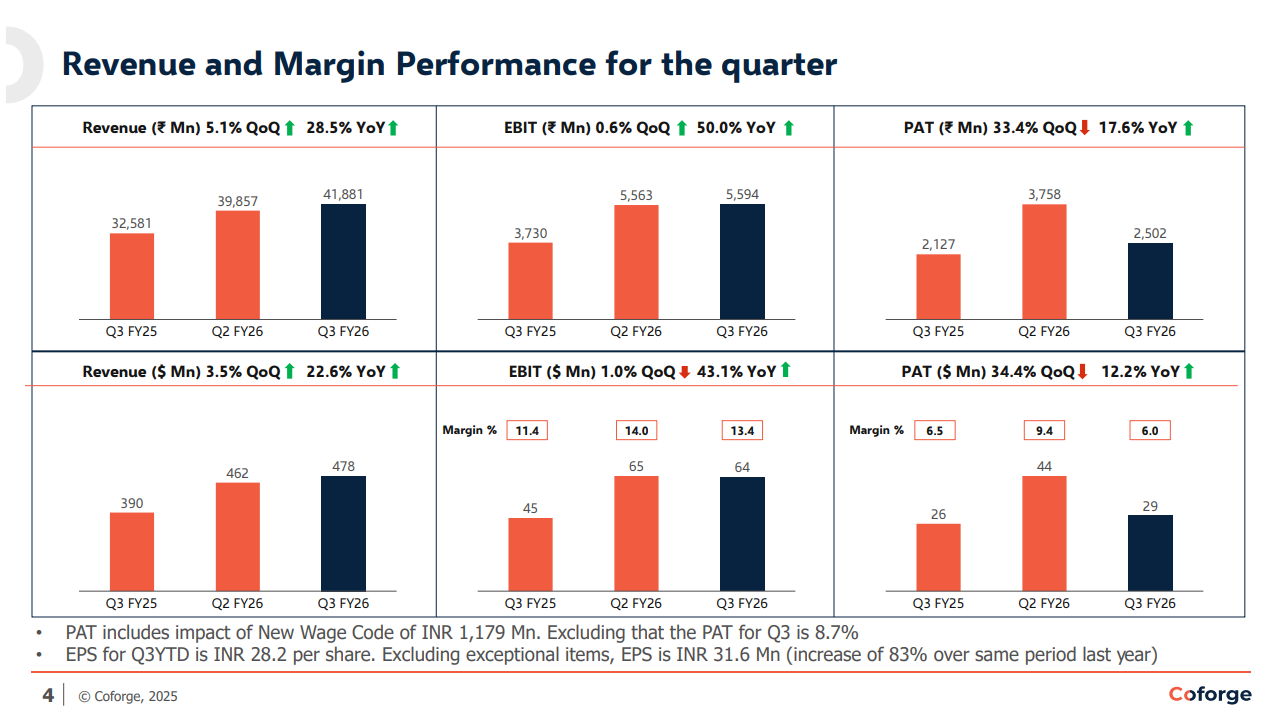

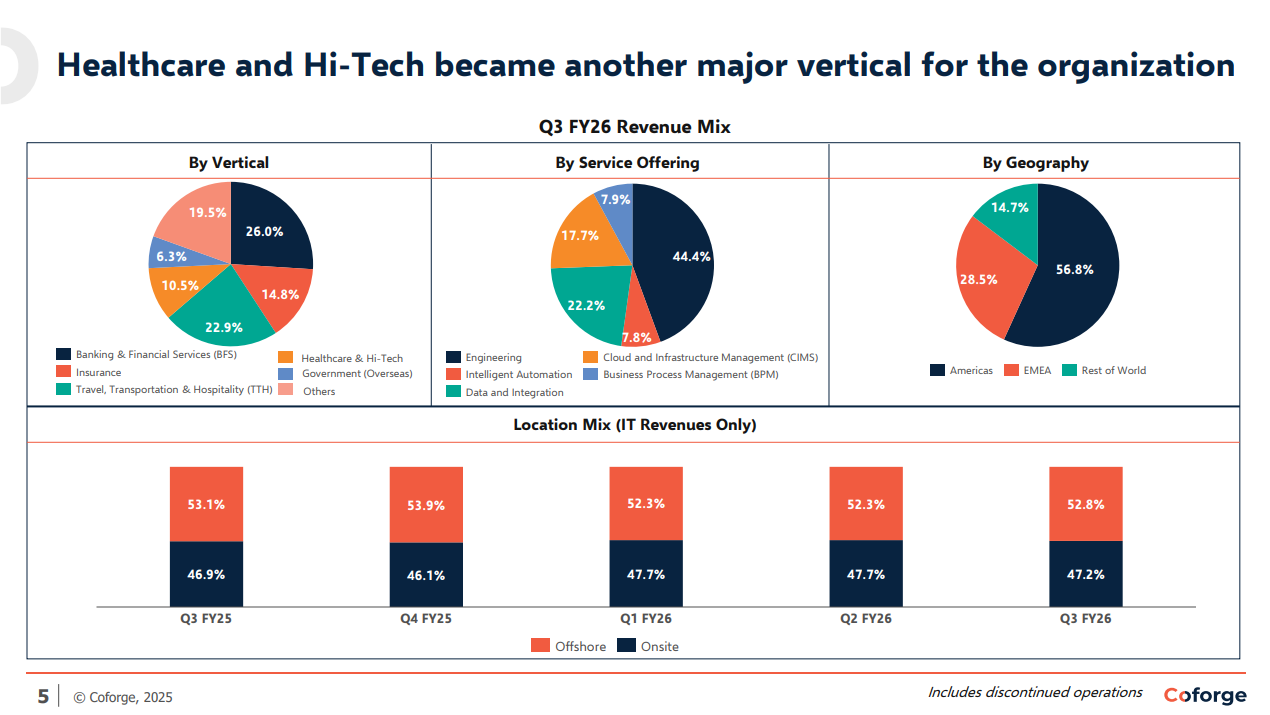

Coforge‘s revenue notched up by an impressive ~22% (in rupee terms) from last year to over ₹4,188 crore. Its EBIT margins came in at 13.4% — an increase of 1.91 percentage points from last year. Its 12-month order book has expanded by 30% from last year. The past year has been the best-performing period in Coforge’s history, even signing their largest deal ever with global travel platform Sabre.

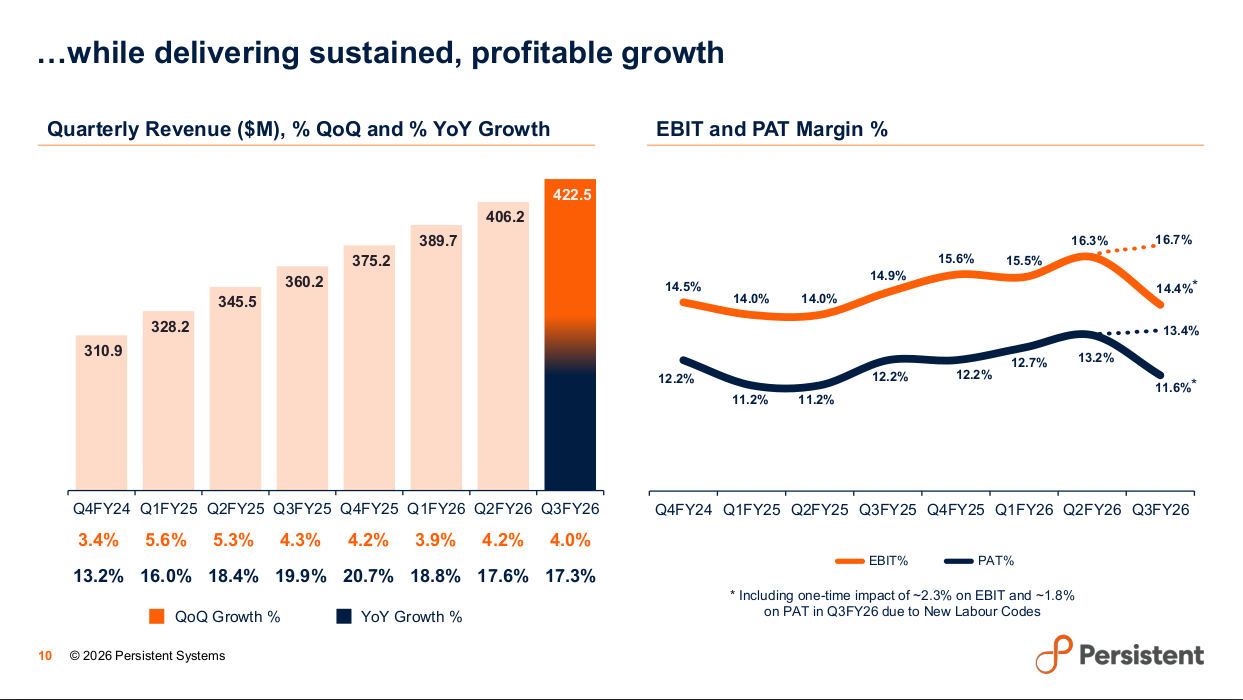

Persistent Systems, meanwhile, reported ~₹3,778 crore in revenue, up by ~23% year-on-year. This is the 23rd consecutive quarter that they’ve recorded sequential revenue growth. Its profit-after-tax margins of 11.6%, however, are lower than what it was in the same quarter last year.

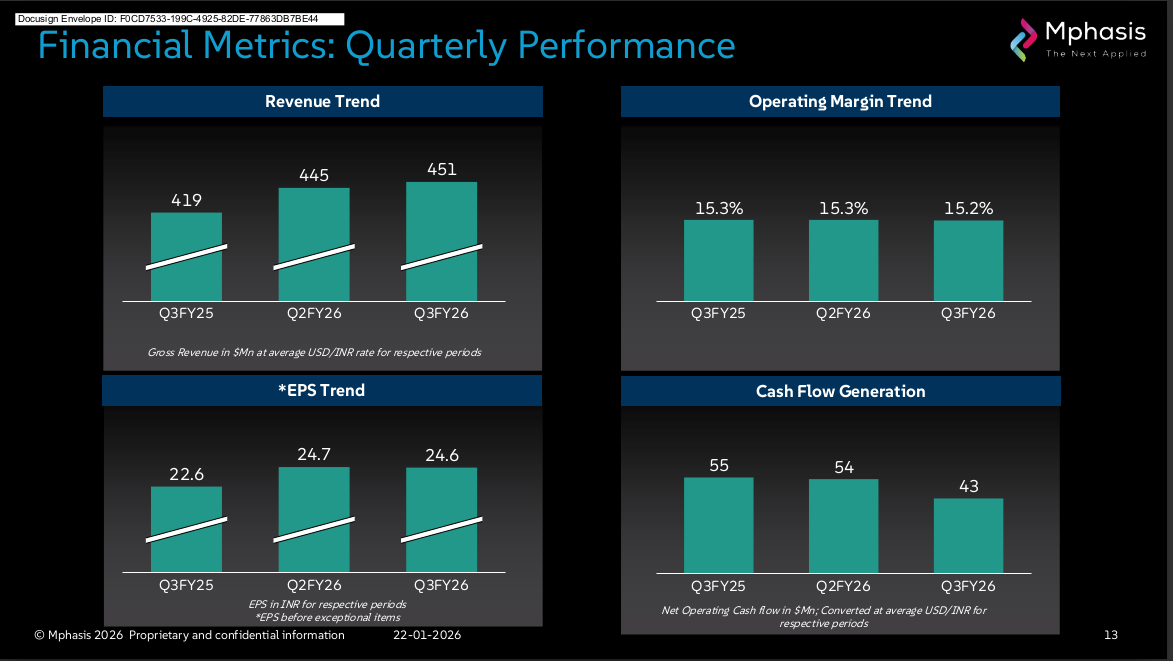

Lastly, Mphasis came in at $451 million (or ~₹4,000 crores), growing 7.4% year-on-year in constant currency terms — slower than its peers. Its EBIT margins — the highest of all three so far — have held steady at around 15.2% for the past year, and that hasn’t changed this quarter. Mphasis’ order book was boosted by four large deals won this quarter, two of which are valued at over $50 million.

The Q3 margins of all three companies require an asterisk, though. Due to the New Labour Codes announced by the Government of India, margins of various companies took a one-time hit.

Persistent’s margins, for instance, were dinged by 2.3 percentage points due to increased provisioning for gratuity and leave encashment. Coforge’s reported profit-after-tax included a one-time impact of ₹117.9 crore from the same provisions. Mphasis recorded an exceptional item of ₹35.5 crore. When you strip out these one-off statutory adjustments, the underlying margin picture looks far healthier for all of them.

The AI transformation

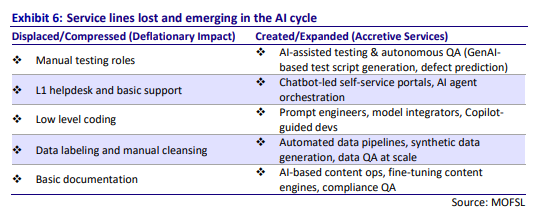

In our recent coverage of tier-1 Indian IT firms, we highlighted a hypothesis by Motilal Oswal on how Indian IT could ride the AI wave. In essence, they pointed out that while AI may deflate certain existing business lines, it could very well open up new ones that Indian IT would be best-positioned to take advantage of. A similar story, they say, unfolded in 2016-18, when Big Tech firms were investing tons of capex to expand cloud services.

While there are signs that large-cap IT firms are now making this transition, the weight of legacy contracts and headcount slows the shift. Midcap IT, though, is moving faster.

AI has already begun contributing to their business in a huge way. A large part of their AI strategy involves autonomous AI agents that can perform multi-step tasks without human intervention.

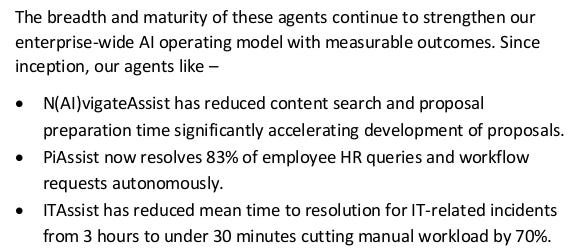

Take Persistent, most of whose clients include hyperscalers like Microsoft, AWS, Oracle and Google — the same companies leading AI-related capex. Persistent has built an agentic AI platform called AssistX. It spawns off autonomous agents to solve IT incidents, employee HR queries, and even develop new sales proposals. The productivity increase of some of these agents has been enormous.

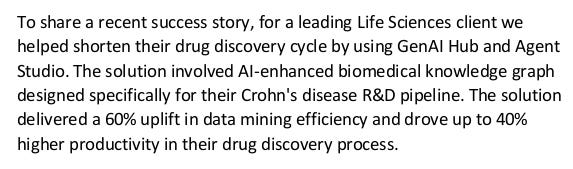

For Persistent, agentic AI is at the centre of many deals they’re now winning. For instance, they mention how, for a life sciences business, they shortened the drug discovery cycle by using their proprietary GenAI products. This, they say, helped increase the productivity of the drug discovery process by 40%.

In essence, now they have built agents that understand problems in pharma, software, banking, and other industries where they’ve won deals. These agents are deployed to solve repetitive problems, like loan origination, document verification, and maybe even parts of drug discovery.

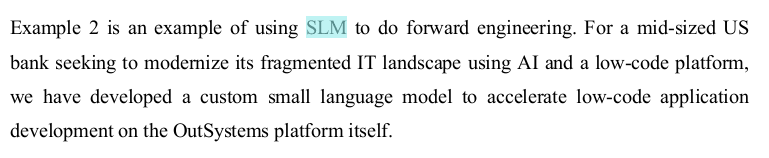

Then, there’s Coforge. Its current earnings call was hardly focused on the business. But last quarter, among other deals, they highlighted how they developed an in-house small-language model for an American bank.

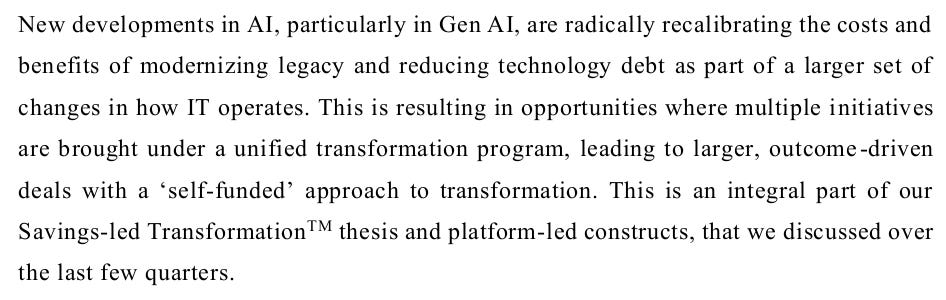

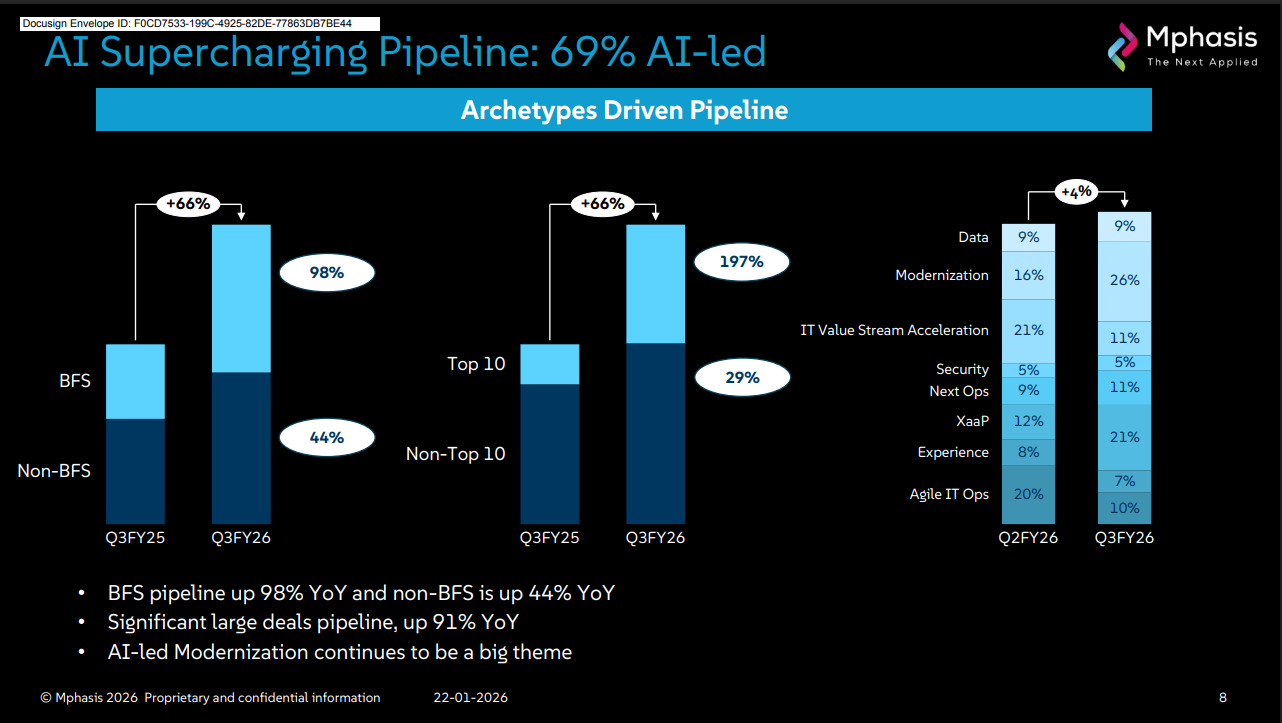

Mphasis, meanwhile, offers their clients an interesting Savings-Led Transformation deal, made possible only by AI. The pitch to clients is simple: let us use AI to automate your routine operations (”squeeze the run”), and we’ll use those savings to fund your modernisation initiatives (”feed the change”) — all within the same budget envelope. More importantly, instead of the old way of billing by man-hours in the IT industry, this model prices by outcomes.

This has boosted their current deal pipeline, 69% of which is AI-led.

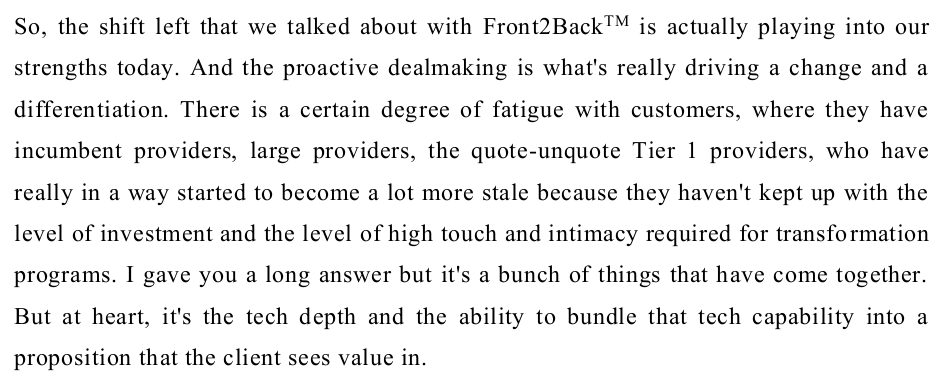

Interestingly, however, Mphasis has also been very blunt in contrasting their AI approach with that of large-cap IT firms like TCS and Infosys. Two quarters ago, they mentioned how their clients are fatigued with the solutions offered by tier-1 firms. That, in Mphasis’ view, is because of their lack of investment in new technology.

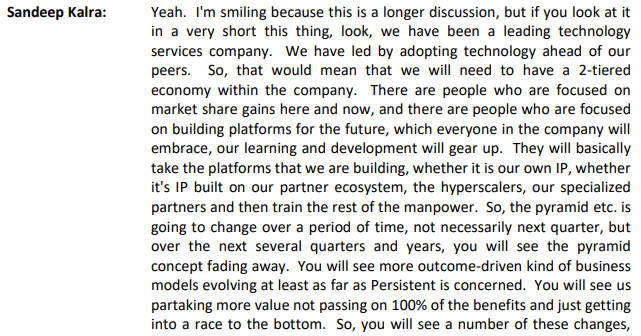

This, however, isn’t new or unique to Mphasis. In our midcap IT primer, we highlighted how Persistent and Coforge were competing away large deals from tier-1 IT firms. Persistent’s CEO, Sandeep Kalra has noted in the past that unlike large-cap peers, they aren’t bloated by headcount. This allows them to disrupt existing contracts by deploying smaller, AI-augmented teams — doing with 20 people what used to take 100.

These are very early signs of the fact that the old, headcount-based model of Indian IT is already shifting to being technology-heavy and outcome oriented. Unburdened by massive headcounts, midcaps are already aggressively pursuing this transition.

The M&A strategy

With how fast India’s midcap IT industry has grown in the past few years, the need to get more capabilities through acquisitions has also risen. The past three-four quarters have seen significant M&A activity. But these acquisitions aren’t done purely for the sake of size. They’re integrated into the broader business strategy of these firms.

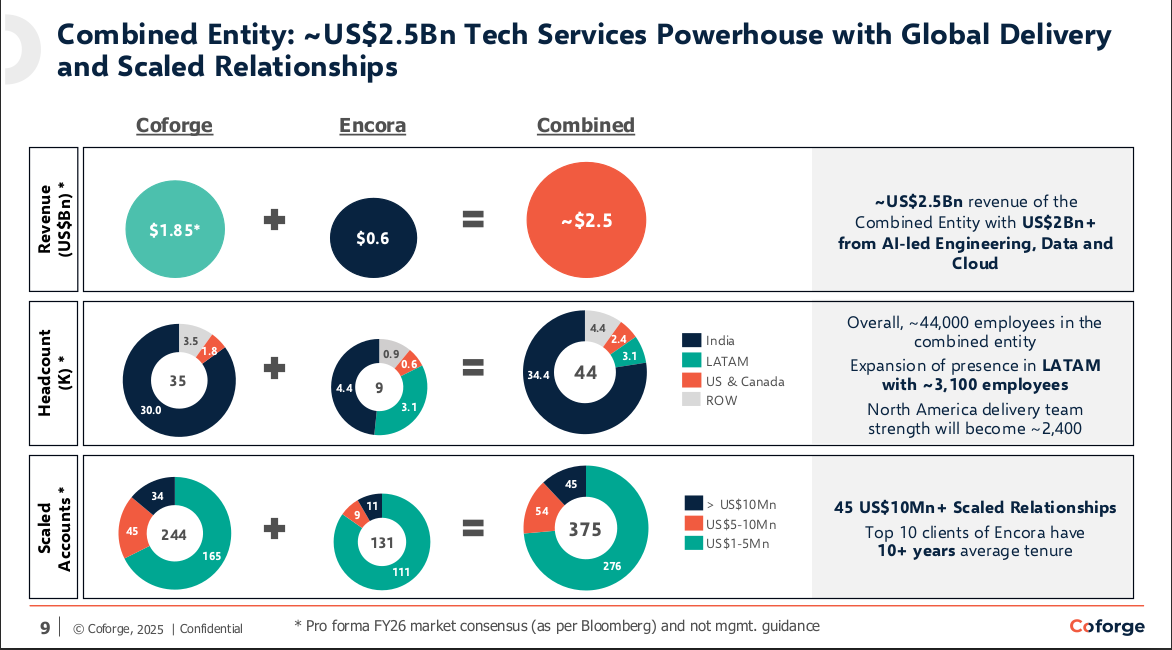

Coforge, perhaps, has led the charge. This quarter, they finalized their largest acquisition ever in US software engineering firm Encora. It will help Coforge jump to an entity that potentially makes $2.5 billion revenue, while also adding complementary skills to their AI capabilities. It also automatically expands their geographic footprint to Latin America.

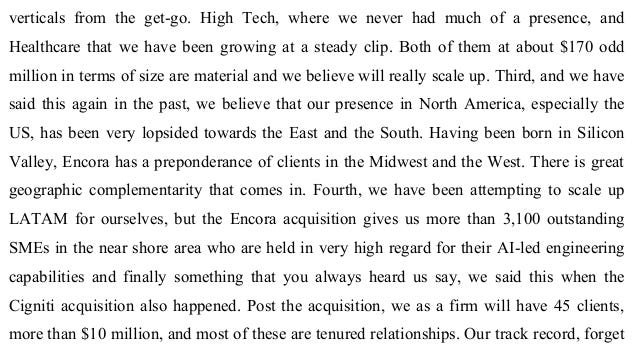

Moreover, just two quarters ago, Coforge acquired Cigniti Technologies. That deal has already begun yielding synergies for Coforge, as Cigniti’s largest clients have already signed up for larger deals with Coforge.

Mphasis, in comparison, has been more measured, but still active. In July 2025, it acquired a 26% equity stake in Aokah, a business that specializes in providing services to global capability centers of multinationals. It also obtained majority control of a software testing business.

Meanwhile, Persistent completed the integration of older acquisitions from 2024, primarily to enhance capabilities in AI and data privacy.

Where deals are being won

Lastly, which sectors are these midcap IT firms winning deals in?

Now, each firm has its own specialization. For example, the largest chunk of Coforge’s clients come from the travel industry. For Persistent, software and high-tech represents their bread and butter. However, midcap IT firms have been showcasing their ability to win deals elsewhere as well.

Most interestingly, across the board, Banking, Financial Services, and Insurance (BFSI) has been one of the biggest growth drivers. Mphasis, for whom BFSI makes up 67% of revenue, saw the vertical grow by 3.7% from last quarter. Persistent’s BFSI business grew by ~29% year-on-year, while Coforge’s BFS business grew by 13.8% annually. But compared to Mphasis, both started from a lower base.

Why is this happening? For one, banks in the US and Europe seem to be doing well. In a high interest rate environment, the margins of banks would naturally fatten. They would have more to spend on new technology projects, particularly those that streamline regulatory compliance.

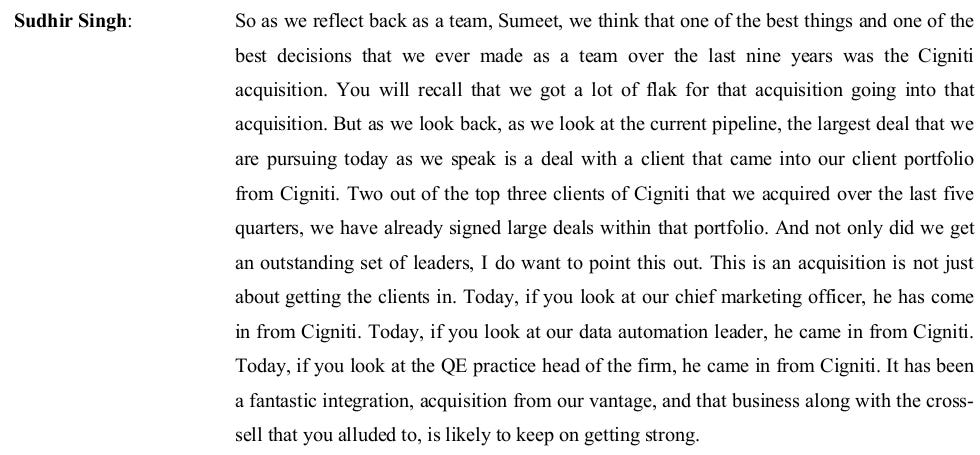

Additionally, insurance has provided a huge tailwind to IT firms. Last quarter, Coforge noted that the insurance industry was entering a new growth phase. The risks being underwritten are getting more complex, and claims are increasing, too.

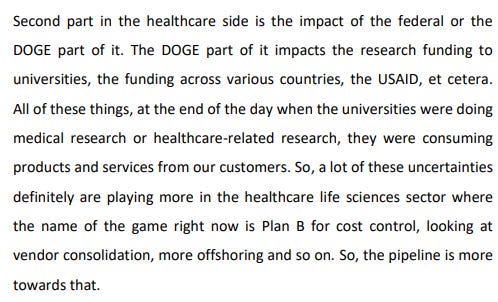

Besides BFSI, healthcare has also grown healthily, particularly for Coforge and Persistent. Many IT firms, large and small, are racing to win deals with hospitals and clinics to digitize their operations, even help with R&D.

For instance, Persistent secured a 5-year, $50 million+ deal (over five years) with a leading US-based professional organization for pathologists to modernize apps, data, and security. As mentioned above, it is also helping a client streamline drug discovery. Coforge’s acquisition of Encora helped boost their “Healthcare & Hi-Tech” business by ~57% y-o-y.

Interestingly, one reason for why healthcare has done well is because of the financial stress faced by American healthcare.

For instance, in Q1 FY26, Persistent noted that, due to the tariffs, as well as the cutting of government funding, healthcare firms were forced to control costs. That would mean reducing the IT vendors that supply them — and such vendor consolidation is work that Indian IT excels in. The effect of that continues to bolster midcap IT’s business today.

Looking ahead

India’s mid-cap IT firms are certainly not passively waiting to be disrupted. The very tools that threaten their business models are being deployed to win market share.

The question is whether this strategy has staying power. If AI capabilities keep improving, clients might eventually wonder why they need IT services firms at all. But that point is still quite far away.

But even besides that, we have barely addressed the risks of being a midcap IT firm — we do mention them in our primer. For instance, compared to tier-1 IT firms, they’re not as well-diversified geographically or sectorally. Additionally, their biggest clients disproportionately contribute to their business.

For now, none of these questions seem to be hurting midcap IT. Some of those questions might also be the source of its rise so far.

The dollar comes in waves

The world’s biggest macro question, arguably, revolves around the dollar. Is the dollar losing its grip on the world? Or is it tightening it? Depending on whom you ask, you’ll hear equally confident accounts of both.

In one version of the story, the Dollar is on a slow, terminal decline. Central banks are hoarding gold, China is building alternative payment rails, and America’s “allies” have been hedging their US exposure. In another telling, there’s simply nowhere out. The dollar has no credible alternatives, and there’s nothing strong enough to break the sheer inertia of a dollar-based global financial system system.

Both camps tend to treat this as a binary question: the dollar is either dominant, or it is doomed. A fascinating new paper from researchers at the Bank for International Settlements, however, suggests that both sides are wrong — or at least incomplete.

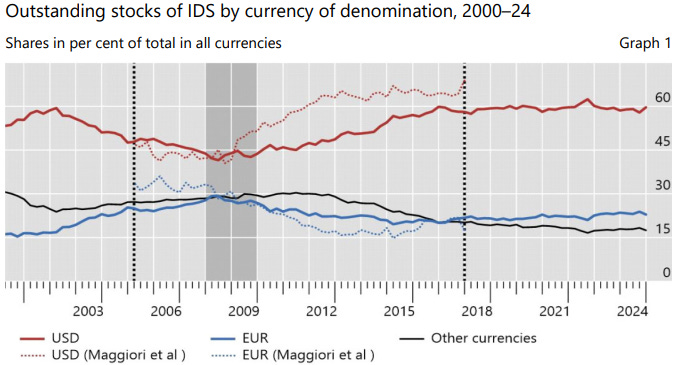

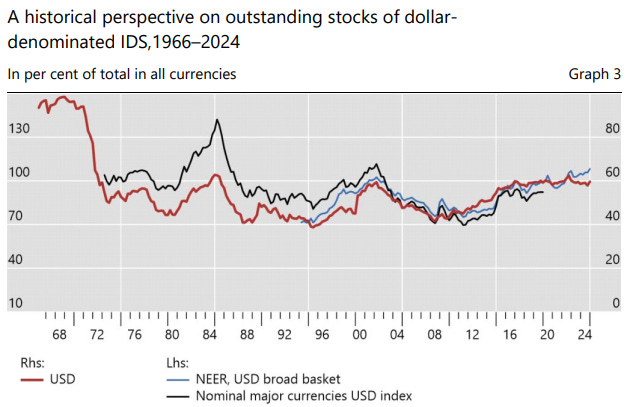

These researchers use what is arguably the most comprehensive database of international bond issuance ever assembled — covering securities from 136 countries, going back to the 1960s. And through this entire period, they find no long-run trend in either direction.

Instead, they find waves. The dollar grows in popularity, then falls, then rises again, and falls again — in a pattern that has repeated at least thrice since the end of the gold standard. The share of the dollar in international bonds today, at roughly 60%, is almost exactly where it was in 1973.

This finding reframes the debate. The question isn’t whether the world is seeing a “de-dollarisation”. It has seen many, already. The broader question is why the dollar has constantly come back on top, and whether things are any different, today, than what has come before.

Behind “dollarisation”

Before we begin, it helps to understand what “dollarisation” actually means.

Most countries have their own currencies. People in India buy groceries in rupees; people in Brazil pay rent in reals. That is the ordinary life of money. But sometimes, a country’s currency is used in an entirely different way — by people who have nothing to do with that country, who do not wish to buy or sell anything with it.

In 2022, for instance, Reliance wanted to raise $4 billion in debt. Ideally, it would have raised this in Rupees, and by-passed any risk that came from the Rupee weakening. But the Indian market was simply too small to accommodate so much debt from its largest company. If Reliance wanted investors with that sort of liquidity, it would have to look outside India. And so, it chose to issue its debt in dollars — even though it was an Indian company, wooing investors all over the world.

A currency’s dominance, in a sense, comes from this sort of preference — where others trust your currency, and what it brings, to pursue their own ends.

The BIS researchers study these preferences through the lens of international debt securities — bonds issued outside the borrower’s home country, like those of Reliance. This is, in all, a $30 trillion market, larger than the entire cross-border loan book of the global banking system. It is, in other words, a meaningful window into which currencies the world actually chooses.

The last de-dollarisation: the “Euro moment” and its aftermath

Reliance’s choice may not have been so obvious, two decades ago.

The dollar was roughly where it is today, at 60% of outstanding international bonds, in the year 2000 as well. The euro, barely a year old, was at a modest 16%.

But importantly, the euro seemed like a credible alternative to the dollar. Over the next few years, its share would grow at a blinding pace. Midway through the decade, new issuances were just as likely to be denominated in the euro as they were in the dollar. By 2008, 30% of outstanding international bonds were in the euro. The dollar’s share, meanwhile, had fallen to just 43%.

The pound sterling, too, had a smaller but parallel wave of its own. From a base of about 10%, its share of international bonds rose to a peak of around 16%.

This was the “euro moment”. A credible de-dollarisation was clearly working its way through world markets. New peer currencies, it appeared, were giving the dollar a stiff challenge. In hindsight, this surge may have been riding a financial bubble, with European banks and financial institutions gorging on leverage to issue euro bonds in vast numbers. But that wasn’t obvious just yet.

And then, the global financial crisis erupted.

The crisis slammed the brakes on new debt. While the American system jumped to the dollar’s defence, European institutions weren’t as forthcoming — sparking the eurozone crisis. The euro, it turned out, had no fiscal backstop, and no lender of last resort. By 2012, its share of international bonds had fallen to about 22%. It has been there, roughly, ever since.

The dollar, meanwhile, surged back. By 2016, its share had climbed to 60% once again.

This was the shape of one entire cycle. And it wasn’t the first one, by far.

This has happened before

In the 1960s, practically all international bonds were denominated in dollars. Then, America would pull away from the gold standard, bringing in a period of turbulence. But with extremely high interest rates over the 1970s, investors the world over flocked to American markets. It would hit a peak, once again, by 1984.

But in November 1979, a shock showed how vulnerable their US holdings were. After revolutionaries seized the American embassy in Tehran, President Carter froze $12 billion in Iranian assets.

As the historian Nicholas Mulder has noted, the freeze sent shockwaves through the oil-exporting world. OPEC states, which had recycled their petroleum earnings into dollar deposits through the 1970s, began diversifying aggressively. Saudi Arabia shifted to holding just a third of its reserves in dollars by 1986, spreading the rest across Deutschmarks, yen, and Swiss francs. Libya and Iraq piled into gold. By the second half of the 1980s, a de-dollarisation was underway. The dollar’s reserve share would fall to 48% by 1990.

But then, there was another wave. America all but “won” the cold war, emerging as the undisputed hegemon. A wild technological boom cemented its supremacy. Elsewhere, meanwhile, a financial crisis was rippling through Asia, while Russia defaulted on its debt in 1998. By the end of the millennium, the United States had reached another peak.

And then, the cycle began all over again.

What drives these waves?

What, exactly, are we seeing here? Are there shifts in the preference borrowers and investors have for different currencies? Or is this a mere correlation, reflecting deeper change in the background?

There are a few things that complicate this analysis.

One is composition effects. There are some countries that structurally prefer one currency. Many emerging economies are all but locked into the dollar. European countries, meanwhile, prefer the Euro. If emerging economies grow faster than European countries, for instance, then the dollar’s aggregate share would rise — even if there’s no real shift in preference.

Another is currency valuation. If the dollar grows stronger than the euro, that might make dollar-denominated debt appreciate, even if there’s no change in lending activity.

Both factors play a role, it turns out, but neither explains the wave. Even if you control for all that, these waves show up. There’s a genuine, tractable change in preferences. By and large, countries’ preferences are remarkably sticky. Borrowers from the same country generally tap the same markets for debt or investment. But the intensity of that preference keeps changing.

The biggest impact, it seems, comes from the preferences of advanced economies outside Europe and the United States. Countries like Japan, Australia or Canada, for instance, have no strong structural reason to prefer one currency over the other. Their choices are responsive to conditions — like interest rate differentials, the perceived safety of the issuing currency’s institutional framework, the depth of the relevant investor base, and so on. When these countries change their choices, the wave moves.

Consider Japan, in the last wave. Between 2000 and 2008, the dollar’s share in Japanese international bonds fell drastically, from 44% to 18%. After the crisis, however, it rebounded — surging to 76% by 2024.

Why waves break

All of this is to say, the question “is the world moving towards de-dollarisation” is an incomplete one. Right now, the data suggests that the dollar is near its peak. In a few years, it could well see another downshift. These episodes come and go, however.

The better question to ask is: why didn’t the previous downswings stick? And is there something different this time?

Nicholas Mulder offers a useful framework through which to think about this: historical de-dollarisation episodes have tended to be fast and narrow. They’re usually driven by panic — sudden shocks send investors scrambling for alternatives. But the alternatives, usually, are few. When the panic subsides, or when the alternative itself runs into trouble, money flows back. The dollar wins by default.

That’s what happened with the euro. The dollar had taken a series of dents — from the dot-com bubble being punctured, to corporate governance scandals like that of Enron, to its wars in the Middle East. Meanwhile, there was a promising new currency backed by a large economic bloc. It attracted many. But when stress-tested by a genuine crisis, its institutional gaps proved fatal. The euro’s bid for financial supremacy collapsed, and has never recovered since.

Could the current environment produce a different outcome? There are reasons to think it might. Ever since the United States froze $300 billion worth of Russian assets, as the Ukraine war erupted, many countries are looking for alternatives. Investors from “allied” countries, too, are shifting their portfolios away from the United States.

No alternatives are readily apparent, just yet. But there has been a broad-based move by non-Western central banks into gold. Naturally, this isn’t visible in the data on debt issuances, but the dollar’s reserve share has fallen from 71% in 2000 to 57% in 2025. This is a process that has played out over a long timeline, but that might make it that much harder to reverse.

For the time being, there isn’t really a strong alternative currency for debt issuances. But China has been pursuing a long-term, deliberate effort to build renminbi-based infrastructure. This is slow, and hasn’t drawn much trust just yet — particularly since people don’t completely trust the Yuan as a store of value. But there’s a shift visible at the margins in the BIS data, with its share of international bonds rising from zero to rival that of the yen.

We can’t offer predictions

If there’s one thing to take away from the BIS paper, it is that the dollar is resilient. It has faced many crises in the past, and has survived all of them. It has bounced back, victorious, after losing large leads to a variety of rivals. You can never be too cautious in calling the death of the dollar.

It is perfectly possible that any multi-decadal, slow-moving drift you see in the data will abruptly reverse itself, the next time the world’s financial system faces a genuine test.

But as Mulder points out, if any rival is to take the dollar’s place, it will do so over a long, grinding war of attrition — not a sharp drop. That’s precisely the sort of thing that isn’t visible in the data… until it is.

Tidbits

Mining giants Rio Tinto and Glencore scrap their $260 billion mega-merger, killing what would have been the world’s largest mining deal. Glencore said Rio’s proposed terms significantly undervalued its copper business and growth pipeline. This marks the third failed attempt at a tie-up between them, following collapsed talks in 2014 and late 2024.

We published our copper story just 2 days before this decision.

Source: FTKotak Mahindra Bank and Canada’s Fairfax Financial have submitted their separate financial bids for a majority 60.72% stake in IDBI Bank, jointly held by the government and LIC. The deal, valued at nearly $7 billion at current market prices, is one of India’s biggest banking privatisations.

Source: ETThe government has revised the Startup India recognition framework, doubling the turnover limit from ₹100 crore to ₹200 crore and introducing a dedicated “Deep Tech Startup” sub-category with a ₹300 crore turnover cap and a 20-year eligibility window — twice that of regular startups. The move aims to channel patient capital into R&D-intensive sectors with long gestation periods.

Source: The Hindu Business Line

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Pranav

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

As mentioned in the IT mid caps article, ".....we do mention them in our primer...."

Which primer are you referring to