Android on trial

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Google knocks on the Supreme Court’s door

The unseen ways Indian farmers adapt to extreme heat

Google knocks on the Supreme Court’s door

Google just approached the Supreme Court, asking it to intervene in a major antitrust case. Our entire digital economy could be at stake. The case could change how Indians pay for Android apps, how app developers run their businesses, and the extent to which tech giants can step on others’ toes to favour their own services.

At its heart, the case concerns Google's control over Android — the operating system behind almost all of India's smartphones — and its controversial requirement that app developers can only use Google's payment systems, paying commissions as high as 30%. Beyond the immediate financial implications, though, are deeper questions: What limits should exist on the power of tech giants? Should they be treated like any other business, with complete freedom to maximise their own profits? Or does their central role in the digital economy bring additional responsibilities?

Let’s dive in.

Understanding the conflict

Android as an ecosystem

The market for consumer technology products is weird. Take phones: you don’t buy a smartphone to enjoy what the phone, as a physical device, gives you. That’s simply a platform. The true value of your phone comes from all the different abilities that different apps bring to your phone.

To get to that app, you ordinarily go through the Google Play Store — Google’s pre-installed digital marketplace. This is the main portal through which you reach an app developer. But Google’s role doesn’t end there: it runs a whole ecosystem. If Play Store were a digital “mall”, Google would also be the architect, the security guard, the payment processor, and a shop owner competing with its own tenants.

All Android apps, in short, play completely within the guardrails that Google sets.

That gives Google sizable control over India’s smartphones as a whole. Android powers more than 95% of smartphones in India. This allows it a tremendous level of control over anyone that tries to serve you on your phone.

Is this control fair? This is the question that’s travelling through our legal system.

Payments

To different developers, Google’s control looked different. Take payments:

97% of app developers just pay a one-time registration fee of $25 to list their apps on the Play Store.

But the remaining 3% — those who charge for apps, or offer in-app purchases — have a very different financial relationship with Google. They must pay a 15-30% commission on every transaction. For instance, if you pay ₹1,000 a month for a premium subscription to a dating app, Google would take ₹300 out of that payment before the app developer sees a single rupee.

To enforce this, in September 2020, Google made a huge change to how it ran things. A developer that offered paid apps or in-app purchases would now have to use the “Google Play Billing System” or “GPBS” to process payments. Before this, app developers had a lot of flexibility in processing payments. Some used Razorpay, others integrated PayTM, while many had their in-house payment systems. The new policy gave them roughly two years to wind those up and migrate to Google’s systems. It didn’t matter if the alternative was cheaper or more efficient.

This gave Google direct visibility over all the money that any developer got. And it gave it the ability to deduct its commission directly, before passing anything to a developer.

One way developers would try to get around these steep commissions was to tell push users to cheaper payment options outside the Play Store. Their app may, for instance, take you to a web link through which you could pay the developer directly, without Google’s commission. The new policy tried to plug this loophole with strict “anti-steering” provisions. Developers couldn't add links, messaging, or UI flows that nudged users towards different payment methods. Google was practically bidding for control over the content of Android apps.

There was an exception to this rule, however: YouTube.

YouTube did not need to go through GPBS — it had separate agreements with third-party payment processors, and paid them ~2.3% for payment processing, instead of the 15-30% commission Google demanded from others. To Google, this was reasonable: they ran YouTube, and its revenues were Google’s own revenues. To others, though, this was plain favouritism. It put YouTube at an advantage over a video streaming service like Disney+ Hotstar — letting it offer services at a much lower price point.

UPI discrimination

One place that Google’s control rankled its rivals was UPI.

Most Indian consumers that make digital payments prefer going through UPI. And Google’s own UPI app, Google Pay, is locked in fierce competition with rivals like PayTM and PhonePe for market share over UPI transactions. When it came to Play Store transactions, though, it was as though this competition didn’t exist.

If you wanted to make Play Store payments using UPI, different apps gave you starkly different experiences. Google Pay users enjoyed what’s called "intent flow". Clicking the “pay” button automatically opened Google Pay, gave you a quick confirmation, and completed the transaction.

Other UPI apps, however, were relegated to a cumbersome "collect flow". You had to manually enter your UPI ID, switch apps, wait for a payment request to show up, approve the payment, and then return to complete your purchase. This was nowhere nearly as seamless.

This had a major effect on what apps people used. Outside Google’s ecosystem, PhonePe commanded 46% of India's UPI market, while Google Pay held 34%. On the Play Store, however, Google Pay had the largest share of UPI transactions. The very design of the Play Store’s checkout system, it seemed, was built to give Google Pay a massive headstart.

The data dimension

Google’s biggest advantage, however, came from data.

As all payments began moving through GPBS, Google got complete visibility into the economics of every Android app. It could learn which users spent money on what apps, when they subscribed, when they cancelled, their payment patterns, their price sensitivity, and more. At least in theory, this allowed Google to work on its own offerings, advertise better, find the best monetization strategies, and determine what category to build for.

Hungama, for instance, complained that Google could identify their premium users and target them directly with YouTube Music subscriptions, luring them away. MapMyIndia, similarly, complained that usage data from their navigation app could benefit Google Maps. And so on.

The legal case

This was the situation that landed up before the Competition Commission of India (or CCI).

The CCI is tasked with enforcing “competition law”. At its heart, competition law concerns itself with firms that have too much “market power”. It stops powerful companies from rigging the market to put themselves ahead of their rivals.

The CCI’s findings

To the CCI, Google was a “dominant” entity. Most Indian phones ran on Android, and most Android apps had to go through the Play Store. That gave Google a serious amount of power — enough power to steamroll over any app developer that was targeting Android users. If Google decided to “abuse” this dominance, it could create serious problems for other businesses.

The big debate, then, was whether Google actually abused its power. And for that, the CCI had to answer the following questions:

Could Google force every app to use its payment system, and automatically deduct a 15-30% commission? To Google, this was a perfectly normal thing to do. After all, it ran the very platform that made “app development” a viable business. Wasn’t it allowed to collect a reward for that? If anything, its platform ensured that all Play Store payments were safe and reliable. To the CCI, on the other hand, this seemed like extortion — Google owned the very pipeline through which an app developer could reach a customer. Its “business practices” could make or break the entire industry.

Was Google allowed to discriminate in favour of YouTube, allowing it cheaper payments than any of its rivals? To Google, this was a non-issue: if all that money came to Google anyway, how did it matter if that revenue belonged to YouTube, or to Play Store? Both were practically the same entity. To the CCI, however, it seemed discriminatory that anyone that wanted to rival YouTube would have to pay many multiples of what it did.

Was it wrong for Play Store to offer Google Pay users a smooth, one-click payment experience? To Google, this looked like innovation. Because it owned both services, it could make them feel seamless, in a way that it simply could not, with the apps of others. To CCI, however, this looked like even more discrimination.

Was it fair that Google could see the data of the very apps it was competing with? To Google, this was only natural. All platforms collected data, and that data helped them do more for their users. To the CCI, however, this was far too much power — and could theoretically help Google push out any app developer it turned its sights to.

The CCI eventually took an expansive approach, seeing abuse in all these practices.

At its heart was a simple idea: Google was a “gatekeeper” — it controlled the very existence of so many other businesses. That gave it immense power, but with that power came special responsibility. Google couldn’t behave like any other business; it had to do everything it could to play fair.

And so, it slapped Google with a massive penalty — ₹936 crores — and laid down a long list of things Google was no longer allowed to do. For instance, it could no longer require that apps go through GBPS; it could no longer use the data it collected from such apps; it couldn’t create a better flow for Google Pay, and so on.

The appeal

Google, naturally, was unhappy with these findings. And so, it filed an appeal before the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal, or NCLAT. The CCI, the company argued, had gone too far — it had made up responsibilities that were nowhere to be found in the law.

Earlier this year, the NCLAT came out with its order, where it was far more measured.

Fundamentally, the NCLAT disagreed with the notion that Google was a “gatekeeper,” or that it had any special responsibilities. These were noble ideas, but they weren’t actually in the law. The law did not require Google to meet any special standard of conduct. Under the law, an entity could only be punished if there was actual proof that a company was hurting its competitors. Without concrete evidence to say so, you couldn’t simply ask Google to behave “fairly”, or punish it for not doing so.

The CCI, in a sense, was trying to correct everything it found wrong with the way the digital economy worked. The NCLAT, in contrast, was only concerned with enforcing the law that was actually there on the books. For anything else, the parliament would have to pass new laws.

At the same time, the NCLAT didn’t let Google completely off the hook. It found two problems: one, it was still illegal for Google to force apps to go through its payment systems; and two, it was still unfair for it to integrate Google Pay better than any other company’s UPI app. It directed Google to stop both, but did away with the CCI’s other directions. And it slashed the penalty by 77% — asking Google to pay up ₹217 crores.

A short while later, the NCLAT passed another order, claiming it made a mistake. There, it asked Google to stop using billing data to advantage itself, and set out a clear data-sharing policy.

What now?

Google isn’t happy with NCLAT’s ruling either, and so, it has filed a series of appeals against the decision, before the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has agreed to hear the matter, starting in November.

The Court faces a delicate balancing act. Push too hard against Google, and you risk disrupting a system that, for all its flaws, has helped millions of users enter the internet age. Let Google off too easily, and you might give tech giants a free pass to squeeze competitors and extract rents from the digital economy.

There's no perfect answer here, and yet, the stakes are high. Whatever the Supreme Court decides will shape not just how we pay for apps, but how India thinks about regulating the handful of companies at the heart of our digital lives. In a country where smartphones are often people's first and only computer, that's a decision that matters to everyone.

The unseen ways Indian farmers adapt to extreme heat

Imagine a scorching hot day in rural India, with the thermometer touching 45°C during the growing season. In cities, many of us would find relief in air conditioning. But India’s rural families — many of whom work on miniscule farms — that single day of extreme heat ripples through their lives in profound ways. It affects what they eat, how they work, how they spend money, and how they survive.

These unseen effects are found in a new paper by researchers Paul Stainier, Manisha Shah and Alan Berreca. They survey a massive 3 lakh rural households across India from 2003 to 2012 — many of whom grow food for themselves rather than for sale.

The paper has a simple hypothesis: When extreme heat destroys crops, what really happens to the families who depend on those crops? Can they adapt easily? Or do such days throw their lives in disarray.

Their answers reveal the painful ways in which climate change cuts into Indian agriculture every summer, driving millions of Indians to fight for mere survival. And as global temperatures rise, this problem will only grow worse.

What the researchers were studying

There’s a simple correlation one expects between extreme heat and farmers’ lives: extreme heat kills crops. All that food disappears, and so people go hungry — eating fewer calories.

But the researchers found that the relationship is more complex, and interesting.

A nutritional crisis for rural India

The researchers came across a puzzle: extreme heat didn't seem to affect the average calorie consumption in the households they were studying.

They were trying to understand what happened when there was one day in a season when the heat crosses 43°C, two days when it did, and so on. And oddly enough, for one day above 43°C during the growing season, the overall calorie intake barely budged. How was that?

The real story lies in the details.

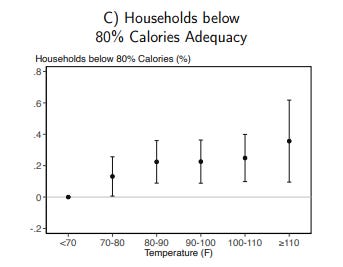

When temperatures cross 43°C for a single day, the share of households that suffer "strong undernutrition" — or 80% below their recommended calorie intake — went up by 0.36 percentage points. That is, a single day of extreme heat in a season pushes about 3 million people into food insecurity.

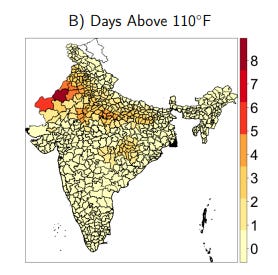

A tenth of our population experienced more than two days of extreme heat. Certain states, like Rajasthan, saw more than ten such days. Imagine that. Such episodes would push one in every thirty households into under-nourishment.

And yet, the average calories people consumed didn’t seem to budge.

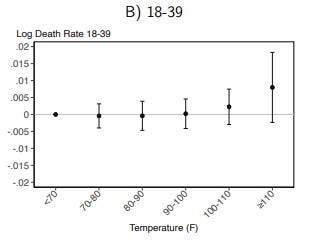

Why is that? The researchers found one partial, horrifying explanation for this paradox: extreme heat increased the mortality rate. In other words, as the number of extreme heat days went up, many people simply died due to heat stress.

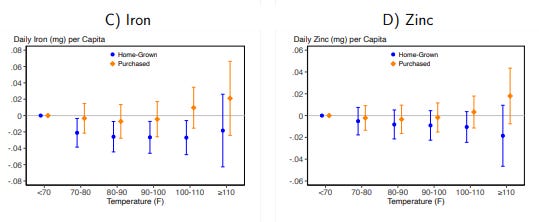

Overall calories, though, are just one thing. Extreme heat also creates many nutritional deficiencies.

Take iron deficiencies. Most of India is already deficient in iron — 54.7% of households consumed less than 80% of recommended iron intake in normal times. This creates serious issues for us Indians — anaemia, lower energy levels, mental health issues, and more. With extreme heat, this only gets worse. That’s especially true with families that are already strongly under-nourished.

Extreme heat also causes other deficiencies — in nutrients ranging from zinc, to thiamine, to niacin.

The costs of adaptation

How do households react to bouts of extreme heat?

The researchers found that they adapt. If extreme heat destroys someone’s home-grown crops, naturally, they don't just accept hunger as their fate. They start buying more food to replace what they've lost from their gardens and farms.

But… where does the money for this extra food come from, especially if their crops are destroyed?

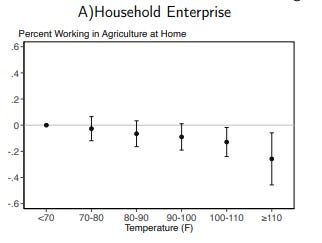

Well, they’re forced to migrate in search of a job. They leave their farms and take up work somewhere else — usually temporarily — after the growing period to find enough money to make ends meet. A single day with temperatures above 43°C sends an extra 0.26% away from their farms — to non-farm jobs outside their home. Heat, that is, creates a massive shift in our labour markets.

While the paper doesn’t cover this, it’s quite unlikely that these jobs are more productive or better paying. People are most probably just finding some way of getting by. We recently covered India’s broken job market, finding that 27% of India’s workforce simply keeps hopping from one informal, low-paying job to another, without any stability. They get stuck in these jobs, with no way of climbing up the economic ladder.

India’s climate migrants probably belong to this group.

For many others, heat can even force people to drop out of their jobs. When the temperature goes above 43°C for just one day during the growing season, the share of working-age people with jobs falls by 0.16 percentage points that year. That is, extreme heat forces a meaningful number of people to lose that year’s employment.

Nor is it easy for people to borrow money to get by. Many of these households have little-to-no access to easy credit. No bank is willing to loan to them. If they can’t find jobs, they have no other way to get relief from an income shock.

What option are they left with? Don’t they have to buy food, after all?

Well, many have to sell assets they might need later — even though they don't have lots of wealth anyway. Alternatively, they might take on debt from informal sources, or reduce investments in their long-term health or education.

The implications are heartbreaking. India’s agricultural families are demonstrating remarkable resilience to climate change, but it comes at a hefty price. They're basically running a sophisticated economic balancing act just to keep themselves fed.

The lowest-income families, in fact, find this adaptation the hardest. They’re the ones that suffer severe malnutrition, and yet, they’re the ones who can't make these pivots easily. They’re less likely to have the skills for non-farm work. They’re less likely to have access to credit to buy food, and they’re less likely to have the ability to teach themselves new skills. And yet, they’re so poor that an economic shock would send them over the edge.

This inequality becomes worse within families as well. The paper points to past research that found that female children generally tend to receive a lower share of resources. Such crises would only further depress this share.

The bottom line? climate change is slowly etching a huge burn scar across the expanse of Indian agriculture. And it’s probably going to get worse.

The policy implications

What does this mean for policymakers, both in India and globally? The researchers provide some practical recommendations.

For one, you can’t just try making agriculture more resilient to climate change. The traditional approach that focuses on farm-based adaptation measures — heat-resistant crops, better irrigation, and so on — simply isn't enough. These families are trying to move out of agriculture, and that will continue as global warming intensifies. You can’t fight that transition. You have to find ways of easing it.

What could that look like? The researchers recommend investing in non-agricultural job opportunities in rural areas. They also suggest making sure people have access to credit when their crops fail, and building better infrastructure, so families can actually access food when they need it.

Second, we need early warning systems, which are connected to direct assistance. You can’t wait to react after a heat-related crisis has hit millions of Indians. That is already too late. Instead, when an episode of extreme heat is forecast or occurs, governments should provide immediate cash transfers — a form of climate insurance — to vulnerable households.

Indian agriculture needs a solution, fast

Hot weather destroys crops, but that’s not where the story ends. Those effects ripple through India’s population, sending some of our most vulnerable people to a cycle of economic misery and adaptation. They struggle to eat; they leave their homes; they sell their property — our climate crisis is actively pushing people into terrible lives.

These challenges are only getting worse as our climate continues to change. And it isn’t something we can wish away. There’s just one, billion-dollar question: how do we build systems that can help people avoid the worst?

It’s not an easy question, but it does need to be answered as soon as possible.

Tidbits

India’s cabinet has approved a one-time ₹300 billion ($3.4 billion) payout to state-run fuel retailers — Indian Oil, Bharat Petroleum, and Hindustan Petroleum — to compensate for losses from selling LPG to poor households at subsidized rates. The payout partially offsets a brutal FY25, when LPG under-recoveries totaled ₹413.4 billion.

Source: Bloomberg

Tata Motors reported a 63% YoY drop in Q1 consolidated profit to ₹3,924 crore, hurt by weaker volumes across segments, trade tariffs, and lower Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) profitability. Revenue slipped 2.5% to just over ₹1 lakh crore. The management hopes for a a stronger H2 performance, especially with the October 2025 demerger separating the commercial and passenger vehicle businesses.

Source: Business Line

Nayara got into trouble with the EU over Russian oil. Now, Reliance Industries may pivot back to sourcing crude from the Middle East—particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE—if U.S. pressure forces India to curb its Russian oil imports. With its massive Jamnagar refinery and flexible sourcing strategy, Reliance could quickly adjust to new suppliers as global sanctions tighten.

Source: Reuters

Telecom companies have some relief. India’s Supreme Court has upheld a Delhi High Court ruling, declaring telecom towers as movable property and thus eligible for input tax credit (ITC) under GST. The decision provides major tax relief for telecom players like Bharti Airtel and Indus Towers.

Source: Economic Times

Following its entry into India, Tesla India has signed a nine-year lease for an 8,200 sq ft flagship showroom at Delhi’s Aerocity, paying ₹17.22 lakh per month, with rent set to rise 15% every three years. The deal includes parking, security deposits, and sets the stage for a Gurugram launch as part of its expanding retail footprint.

Source: Business Standard

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Manie

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

For post #2 - it would be interesting to see the results of a similar research done for the period after the implementation of NAFSA 2013 ( national food security act) and the free foodgrain program under it post covid. I understand the paper flags the issue of data availability but my hypothesis is - it should have improved nutritional outcomes. I am also not sure about transition away from agri as it works as a safety net and a shock absorber for our large labor market in times of economic distress eg covid era reverse migration

good brief,

but curious to see a different indian political map, missing parts...