A Greek tragedy

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Has Greece left all its problems behind?

A New Market for Electricity

Has Greece left all its problems behind?

We’ve often talked about how most of Europe has been going through a downward growth slump. But Europe isn’t a monolith. Even in a time like this, it has some bright spots. One of them is one of the cradles of European civilization — Greece.

Greece is lately one of the best-performing economies in the EU. Investors are hogging its bonds. Unemployment, at 7.9%, is at its lowest level in 17 years. And it’ll probably get better from here.

Just ten years ago, things were much darker. Greece was grappling with a severe debt crisis. It was perennially in debt, and its bonds were seen as risky investments. The country needed years of austerity to get out — slashing welfare, salaries, and jobs — causing deep discontent, and violent riots. Back then, it was deemed “The Sick Man of Europe”.

Then how did it become a lifebuoy for Europe? How did it solve its debt crisis, and what costs did it pay for solving it? The answers to these questions are not easy. This is a story of political logjams, crushed hopes, and the pain of a crore people.

How Greece mismanaged its way to crisis

Greece’s debt crisis was largely its own doing.

From the 1980s onwards, the Greek government had splurged public money. It heavily subsidized its public firms, and paid public sector employees wages far higher than what the private sector could. It also had strong welfare and health schemes for its people, allowing them to retire early and enjoy their leisure time.

That faucet of money, however, bred inefficiency. Greek public firms were inefficient, and needed those subsidies to survive. Its welfare schemes were managed poorly. Meanwhile, the country kept racking up debt. By 1993, its debt levels crossed 100% of its GDP. Inflation became a constant headache.

But high debt is a problem many countries deal with. Greece, however, had some unique problems:

Greece’s economy was built around tourism and shipping — two sectors that were specifically vulnerable to international shocks.

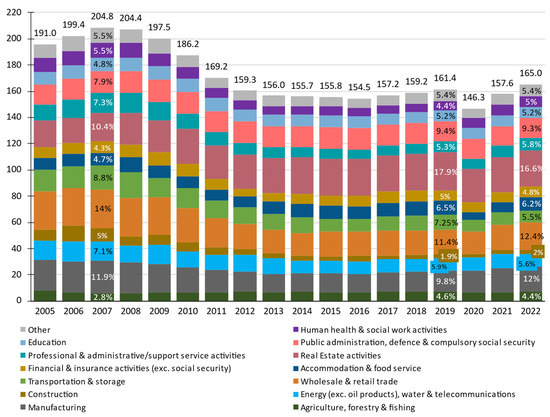

The rest of the economy was lacklustre. It had a weak industrial base — with manufacturing making for just 9% of its GDP. Greek firms were unusually small, and lagged most of Europe in labor productivity.

Meanwhile, many people didn’t pay taxes — with the black market contributing more than 25% of Greece’s output. This hurt its already poor finances.

The promise of the Eurozone

Amidst these problems, at the turn of the millennium, joining the Eurozone seemed like the perfect answer. It gave Greece lower interest rates, a strong currency in the Euro, and economic stability — something it hadn’t seen in a long time.

In return, though, the Eurozone demanded sacrifice. In adopting the Euro, Greece could no longer control its own currency, and it would have little freedom in setting its interest rates. Worse still, it would need strict financial discipline. Its debt could not exceed 60% of GDP, something Greece regularly flouted.

Back then, most Greek people were happy to join the Eurozone. But it wasn’t clear if Greece had the right economic structure to handle its stringent needs. If there were ever a crisis, Greece would have given away the tools to handle it.

But Greece went in anyway. In fact, it was perhaps a little desperate to do so, because it went for some creative accounting to hide its actual budget deficits, in order to meet the Eurozone’s criteria. Meanwhile, they continued to borrow more — money that would end up in real estate and public sector wages, instead of creating industrial activity.

This was a house of cards, with rocky foundations. When the 2008 financial crisis struck, it all collapsed.

The Greek tragedy

When the 2008 crisis hit, money fled most of the world. It suddenly became much more expensive to borrow. Markets were already suspicious of Greece’s ability to pay back its debts, and this instantly made things much worse.

As money dried up, Greece could no longer hide its accounting misadventures. Within a year, it had to reveal that it had obscured its budget deficit. This set off a series of falling dominos that would haunt Greece for years.

2010-11: The first bailout

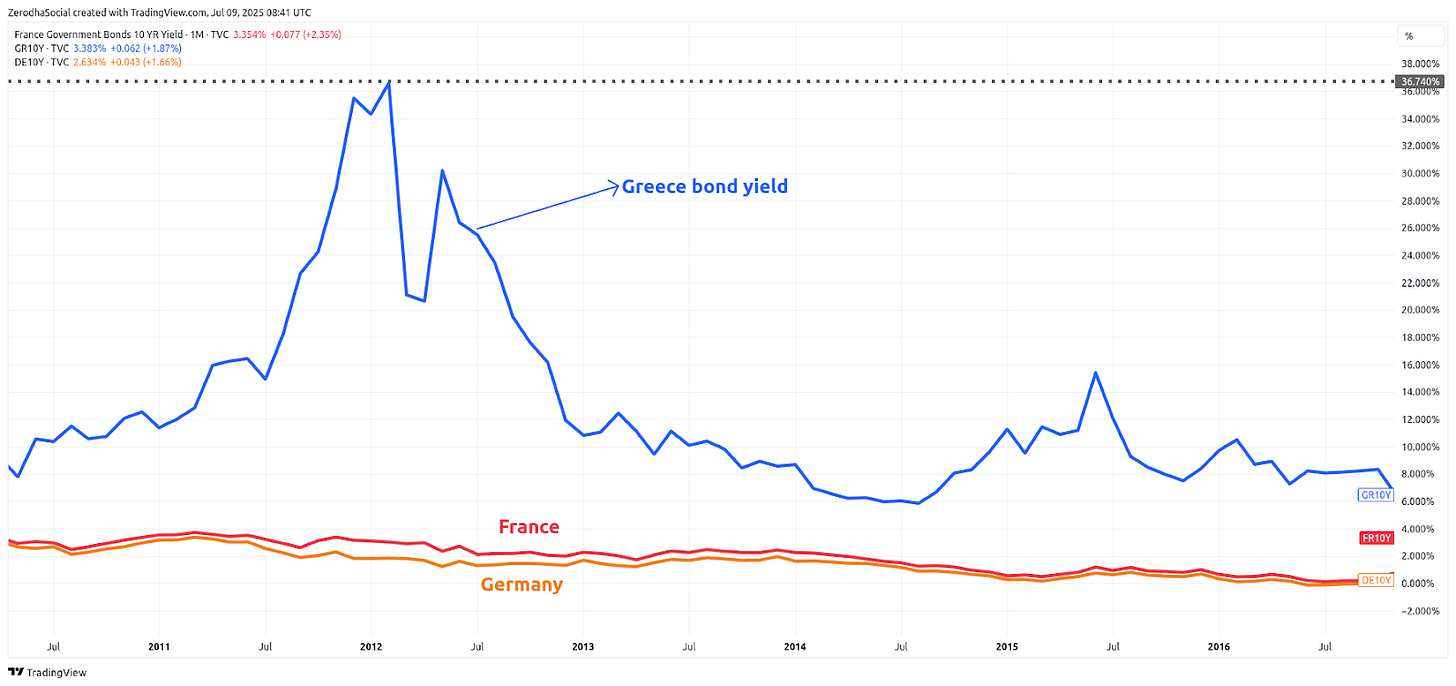

When Greece came clean about its deficit levels in 2010, the markets responded strongly. Greece was suddenly shut out of bond markets. In 2012, yields on Greek bonds were above 30%. Credit ratings downgraded its credibility to “junk”. No one had faith in Greece’s ability to pay its debts any more, making further borrowing immensely expensive.

But Europe couldn’t afford to let Greece default. If Greece was allowed to default, large French and German banks would have to write-off lots of money. Nor could it kick Greece out of the European Union — partly because it didn’t really have a legal mechanism to do so, and partly because pushing Greece out of the EU would destabilise the whole project.

Europe needed a real answer. And so, three institutions — the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund (collectively the troika) — organised a bailout fund worth $146 billion. But it came with strict conditions — called austerity measures:

Greece was forced to cut its budget deficit to 3%, so that it could pay its creditors before spending any money.

Employees were hit hard. Pensions were cut repeatedly, while public sector wages were slashed by 15%. By 2015, pensions were slashed by 40%, and wages by over 35%. The minimum wage was reduced by 22% as well.

It had to privatise many state-owned assets.

Among other taxes, it raised the value-added tax to a massive 23% — in an economy where a huge chunk of business already happened in the black market, and wages were falling.

While all this was meant to keep Greece’s finances in check, the spending cuts created a downward spiral. People spent less. Little money was left for investment. Public debt continued to balloon. The 2008 crisis also dampened the tourism business, with international revenues falling by 20% by 2010.

To the Greeks, life looked much worse in a few short years. Many grew enraged at the troika, blaming them for all the recent troubles. Those years saw bad riots and worker strikes.

2012 — the largest debt restructure in history

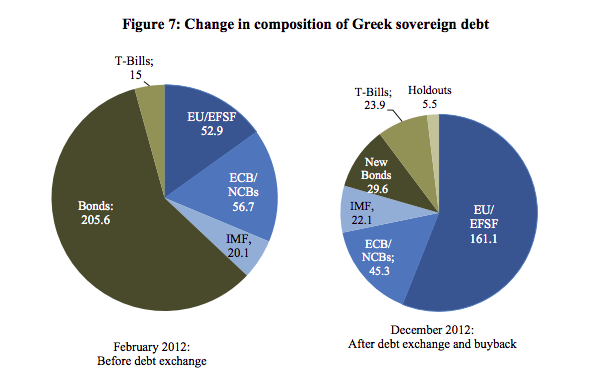

By 2012, Greece needed another rescue. The troika arranged a second bailout package worth $130 billion. This time, however, austerity wasn’t the only solution proposed — a debt write-off by more than 50% was also on the cards. Creditors would eat some of Greece’s losses.

Public European banks were made to buy-back bonds for cheaper than what it cost creditors in the first place. In return, creditors would get a mix of short-term bonds, which could be exchanged for quick cash, and newly repackaged long-term, low-interest bonds.

This was the largest such deal in history. It would give Greece some breathing room.

But sadly, it wasn’t enough. The relief was fairly small in size, and came late. And not all bonds were exchanged — the bonds held by public European banks, worth 20% of total debt, weren’t written off, because those losses would have to be borne by European taxpayers, which nobody would swallow. By the end of the exchange, bond yields continued to be high. Investors just didn’t want to lend to Greece.

If anything, the deal ended up benefiting creditors more than Greece itself, because bond prices spiked once it was announced.

Meanwhile, for this bailout, the troika forced Greece to adopt even more austerity measures. Unemployment soon rose to a whopping 25%. Younger people started leaving the country in droves. By 2015, over 30% of the population was at risk of falling into poverty. All of this despite the tourism business bouncing back.

All this while, things were getting worse. Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio rose from 146% in 2010 to a dangerous 180% by 2014.

2015: crushing hopes

In 2015, amid deep anger among Greek citizens, a new party called “Syriza” won the national election. They promised a radical flip of the power relations that existed so far — they needed favorable bailout terms and more public spending.

Their finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, suggested a program that would link debt repayments to Greece’s economic growth. For a brief while, there was hope of something better.

Only, nothing changed.

It was increasingly clear just how weak Greece’s bargaining position was, in the Eurozone hierarchy. This was a time when the Eurozone was facing problems of its own. The economic pain of the 2008 crisis refused to dissipate. Consumers weren’t purchasing enough to drive the economy forward, creating a situation of zero-inflation. The ECB tried countering this by injecting more liquidity into the system. It bought the bonds of EU countries, worth $1.3 trillion, in exchange for quick cash.

Greece, though, was completely excluded from this exercise despite being part of the Eurozone.

This lopsided power dynamic pushed them to consider quitting the Eurozone altogether. But that didn’t make sense either — their own currency wasn’t strong enough to stand on its own, and such a move would only inflict more pain.

No escape

By now, Greece was stuck between a rock and a hard place. It had just missed a payment to the IMF. It faced a national cash shortage. People were wrapped in panic, thronging to ATMs en masse to get whatever money they could. Greek banks were on the verge of collapse.

The Eurozone was willing to give a third bailout — $94 billion over 3 years — but once again, only if Greece adopted harsh, austere terms. The Syriza-led government had no choice but to break its promises, and adopt these measures.

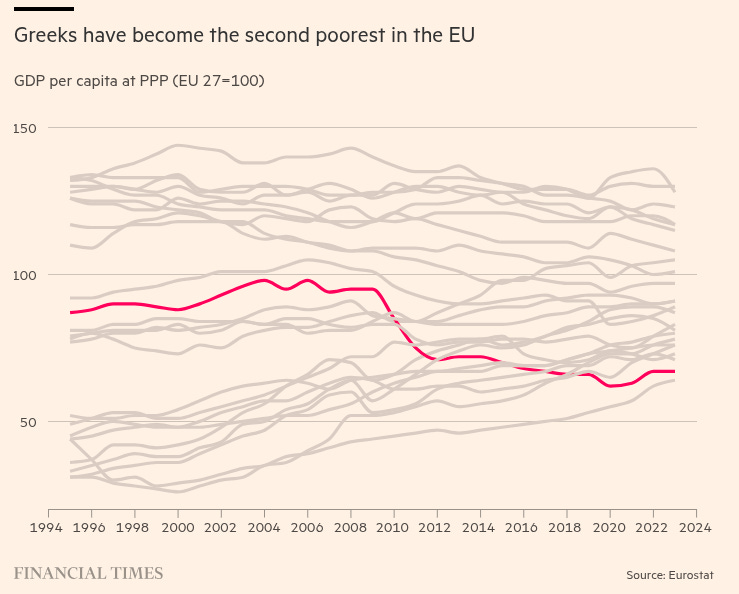

Things had become terrible by now. Greece’s GDP had fallen by 25% over the crisis years. And things refused to relent. Consider this: the US recovered faster from the Great Depression than Greece did from its unending problems.

Recovery — but from what?

In 2018, Greece got the last tranche of funds from bailout #3. There would be no more bailouts.

The next year, Greece saw another regime change — the New Democracy party was now in charge. They were keen on attracting businesses to invest within Greece, and initiated a series of reforms to do so. They increased privatisation, cut various taxes, and set up fast-track procedures for foreign investment. They also forced banks to improve their balance sheets.

These measures have yielded some positive results. In 2022, FDI hit an all-time high of more than $9 billion — improving more than 30x since 2010. Earlier this year, it successfully raised nearly $5 billion in 10-year bonds. In fact, the issue was oversubscribed, with demand worth 10 times that.

Greece’s public debt levels have become a little more manageable. Its debt-to-GDP ratio has fallen from 180% to 150% — still high, but marked by low interest rates and long maturities. It’s now planning to pay more than $6 billion of its long-term bailout debt before it matures.

Business is booming, as the opening of new firms improved by 38% since 2014. Big Tech firms plan to invest at least $1 billion. The government is planning to boost Greek tech startups too, especially in AI.

Most importantly, Greece is trying to change its economy structurally, and be less reliant on tourism and shipping. Manufacturing exports have tripled since 2008.

But things still aren’t rosy, and progress has been slow.

Much of new investment went into real estate — the fastest-growing component — or loan servicing, instead of being used for something productive. Much of its post-pandemic growth has come from tourism, while manufacturing is still a small part of the economy.

One way of looking at this is that Greece had fallen so low that the only way for them was up.

Last year, the Greek economy was still 17% smaller than it was before 2008. Wages have fallen. Living standards have declined sharply. In fact, Greece is still the second-poorest nation in the EU today.

The effects of the crisis still persist.

Earlier this year, Greece saw its deadliest train crash ever. It happened because of outdated infrastructure, which couldn’t be improved due to the lack of public spending. Instead of making necessary public investments, Greece continues to prioritize a budget surplus. And its people are still upset. They continue to riot, as they demand improvements in their lives.

So, did the cure work? Did austerity help Greece? Perhaps, but at a grave cost.

Other crisis-ridden countries should take note. Even an impressive comeback is an ugly time to live through.

A New Market for Electricity

Recently, regulators gave their go-ahead for a new type of contract: electricity derivatives. Trading in electricity futures will kick off on the Multi Commodity Exchange (MCX) and National Stock Exchange (NSE) midway through this month.

What does this do? Well, a futures contract lets you lock in a price today for electricity you plan to buy or sell later. So, this gives power producers, distribution companies, and even speculators a new tool: the ability to secure a future power price, on a regulated exchange — without having to create or take delivery of that power.

Most electricity in India has traditionally been traded through long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs). These are 5, 10, even 25-year contracts between generators and state distribution companies (discoms). Those cover the “baseload” demand.

But electricity demand and supply can swing on short notice — because of heatwaves, rain deficits, outages, you name it. Historically, the only way to make up for gaps was the short-term spot market. India’s power exchanges, like the Indian Energy Exchange (IEX), run day-ahead and real-time markets, where utilities can buy or sell electricity for immediate delivery.

However, those are physical trades. There, you’re actually buying or selling electricity. The new electricity futures are different: they are financial contracts. They’ll be settled in cash, based on a reference price. No physical power changes hands. These trades are a cash bet on the price of electricity for a future month.

But why isn’t IEX launching the derivatives?

Why isn’t the Indian Energy Exchange — the country’s biggest platform for physical power trading — launching these futures itself? The answer comes down to regulation and jurisdiction.

Electricity has a split regulatory structure in India. The physical trading of power falls under the authority of the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC), the power sector regulator. But derivatives like futures are financial securities. This puts them under the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). The IEX runs under the aegis of the CERC, not SEBI. So, IEX cannot offer futures — it must cede that space to a SEBI-regulated exchange.

This regulatory demarcation wasn’t always clear. In fact, this was the subject of a years-long turf war between the two regulators. It took a Supreme Court case to settle it — and that too, only after various ministries came together to hammer out an agreement.

That paved the way for exchanges like NSE and MCX to enter the fray. Anything that involves physical electricity delivery now comes under CERC’s watch, but anything that is purely financial is SEBI’s domain. Zerodha Varsity has an in-depth explainer on this.

This is also why the new electricity futures don’t involve actual power delivery. An MCX or NSE can’t suddenly start shipping megawatt-hours across the grid. They can only allow contracts that where money exchanges hands based on where an index is.

What does it mean for the electricity ecosystem?

That’s about how these contracts work. But what effect would allowing these have?

The primary motivation for introducing electricity futures could be to let people lock in electricity prices and protect themselves from future volatility. Power generators can secure a future selling price for their power, ensuring stable revenues even if spot prices crash. This is especially true for renewable projects — where the supply of energy isn’t entirely in the generators control, and one often has to go to the spot market to sell most of the electricity one makes. As we’ve written before, sometimes, prices literally drop to zero.

Duttatreya Das from Ember Energy pointed that out.

But let us play the devil’s advocate.

A market is only as good as its liquidity – and liquidity, in turn, comes from active participation by those who need the product. So, here’s the big question mark: will India’s public sector discoms — the largest buyers of power — and generators actively hedge using these futures?

It’s hard to say for sure. For example, public oil companies in India hedge their price exposure at only very low levels, covering just their immediate import needs. They’ve long viewed derivatives with distrust — seen as “risky gambles” rather than prudent risk-management tools.

If a similar mindset persists in the electricity sector, the futures market could struggle to attract the volume that makes it truly useful. It might end up as a shallow market, where contracts exist, but few bona fide hedgers are actually in it. And liquidity begets liquidity. If big players stay away, others might not bother showing up.

Without them, this might just become a market dominated primarily by speculators — traders looking to profit from price movements, without any physical stake. This might create a lot of churn but not the kind of stability hedgers need.

On paper, it makes complete sense to have an electricity derivatives market. But that isn’t enough to make it useful. Whether it translates into meaningful benefits to the players in the ecosystem is very hard to predict.

Texas Freeze 2021

No discussion about power markets and derivatives would be complete without revisiting the Texas Freeze of February 2021.

During an extreme winter storm, Texas’s electricity grid suffered a catastrophic failure. Supply from power plants cratered as gas pipelines froze and generators went offline. At the same time, the demand for heating skyrocketed. Electricity prices hit an astronomically high cap of $9,000 per MWh (roughly ₹6.7 lakh per MWh) for days — compared to a normal price of around $50. Millions of customers suffered blackouts at the worst possible time. Financially, it was carnage: some energy firms made windfall profits, while many others were bankrupted in the span of a week.

Now, Texas has contracts and hedges in place for such a thing. You’d think having these hedges would protect companies in such a scenario. Well, some did help — but many hedged players still got burned.

Why? Because when the physical market went haywire, the assumptions behind those hedges broke down. Some power generators, for instance, had sold electricity in advance at fixed prices, thinking they could produce and deliver as normal. When their plants shut down due to the freeze, however, they were incapable of supplying power. But they were still on the hook for those forward sales. To honor their contracts, they had to buy electricity at the $9,000/MWh spot price to cover their positions, leading to colossal losses.

On the other hand, several retail electricity providers who had promised customers fixed low rates couldn’t pass through the insane costs. Instead, they went bust, defaulting on payments. Even a large electric cooperative (Brazos Electric) famously filed for bankruptcy, unable to pay a $2 billion bill for power.

Now, India is not Texas. Our grid is centrally managed and interconnected. The market has tighter controls. A Texas-style winter freeze is a remote scenario. That said, the episode illustrates a problem we should be mindful of — there are “unknown unknowns” when financial contracts meet a commodity as mercurial as electricity. Things can go wrong in ways you cannot predict.

Once you introduce derivatives, you introduce leverage and create a new web of interdependence. A crisis in the physical market can translate into a financial crisis and vice versa. Second-order effects come into play.

The takeaway is clear: as we embrace electricity futures, robust risk management and oversight are crucial. As this exciting new market unfolds, it’s something we’ll be watching closely.

Will discoms jump in and use futures to tame their power purchase costs? Will we get enough liquidity to make prices reliable? How will the first volatility episode be handled? These are the questions on our minds. For now, India’s electricity derivatives journey has just begun.

Tidbits

Earlier, we looked at how major Indian hotel brands are placing long-term bets on location, customer segments, and asset-light expansion. Now, Marriott’s next move shows just how those trends are accelerating.

Ventive Hospitality, backed by Blackstone and Panchshil, just signed seven new hotel deals with Marriott International, adding 1,548 rooms to its portfolio across India and Sri Lanka. Over the next four years, these will roll out across spiritual, business, and leisure destinations — including Varanasi, Mundra, and even a Ritz-Carlton Reserve near Yala in Sri Lanka.

Source: Business StandardWe unpacked the burden of India’s push for steel self-reliance on MSME manufacturers who depend on imported steel. Looks like the government had been looking at it too.

The Steel Ministry has now deferred the 13 June Quality Control Order (QCO) on finished steel imports by four months, after small importers flagged serious concerns. The rule would have forced all importers to ensure BIS certification — not just for finished products, but even for input materials used abroad. This would’ve disrupted shipments already in transit, many of which were ordered months ago.

Source: MintBut regardless of the QCO being deferred, India’s steel import spree has slowed. That has bought domestic prices lower than Chinese shipments in Q126. The drop eases pressure on local mills and may signal a turning point in protecting India’s steel industry.

Source: The HinduAI no longer exists only on our phones and laptops. It’s moving to glasses as well. Maybe we will have even more developments in this field before our next monthly AI round up, but for now, the update is:

Meta has scooped up nearly a 3% stake—about $3.5 billion—in eyewear giant EssilorLuxottica, marking a major push into AI-powered smart glasses. The deal deepens Meta’s long-standing smart-eyewear partnership, fueling its ambition to lead in wearable AI tech.

Source: Bloomberg

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Kashish.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉