SEBI Cracks Down on Front-Running!

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

SEBI's crackdown on front-running

The rise of risky loans, the fall of savings

SEBI's crackdown on front-running

In our first story, we’re covering a large front-running case recently uncovered by SEBI, India’s securities regulator.

Before diving into the details, let’s first break down what front-running actually is for those new to the markets. Simply put, front-running is when someone uses confidential information about a big client’s upcoming stock or derivatives trade to place their own trades beforehand. The goal is to profit from the price movement triggered by the large client’s trade.

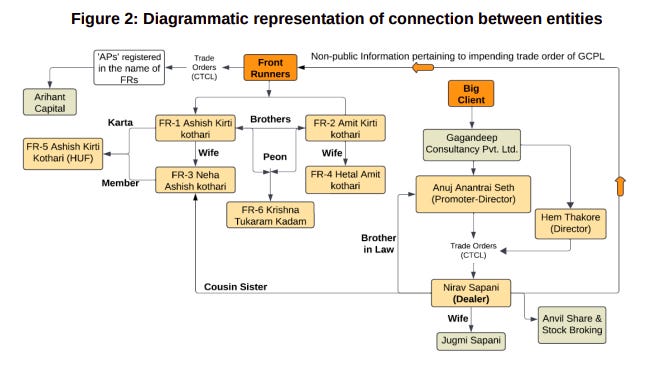

In this case, SEBI believes there was a carefully planned operation involving eight individuals who exploited one large client—Gagandeep Consultancy Private Limited.

At the center of this scheme were two brothers, Ashish and Amit Kothari, along with their wives, Neha and Hetal. The brothers ran a small stock broking business under Arihant Capital Markets. But their real advantage came from their inside man—Nirav Sapani, a dealer at Anvil Share & Stock Broking. Nirav had access to Gagandeep’s trading instructions and was uniquely positioned to leak them. Even more intriguingly, he was related both to the Kothari family and to the individuals placing orders at Gagandeep, making this a tightly knit, family-driven plot.

The execution was straightforward. Nirav, while working at Anvil’s dealing desk, would receive Gagandeep’s trading instructions. Instead of simply placing the trades, he would call the Kothari brothers from Anvil’s landline—speaking in Gujarati—and relay details about the stock or derivative, the trade size, and the pricing levels. Armed with this information, Ashish and Amit would immediately place their own trades, securing the best possible prices before Gagandeep’s large orders moved the market.

To mask their activity, they spread these trades across multiple accounts in their names, their wives’ names, and their Hindu Undivided Family account.

Over five years, from 2018 to 2023, they pocketed illegal profits of roughly ₹4.82 crores, mostly from derivatives, which can be highly profitable when you know exactly how the market will move. But since Nirav was the key insider, they had to share a cut with him. Instead of direct transfers, they funneled money through the bank account of their office peon, Krishna Kadam, who officially earned just ₹10,000 a month. SEBI’s records show ₹1.36 crores was routed to Nirav through Krishna’s account, with additional transfers sent to Nirav’s driver and his wife, Jugmi.

What stands out is how little effort they made to conceal their communication. SEBI reviewed recordings of hundreds of phone calls from Nirav to the Kotharis, mostly during market hours, all from the same two landline numbers at his workplace.

The correlation between Nirav’s instructions and the trades executed was striking, with a near-perfect match in some instances—clear evidence that this was no coincidence.

Once SEBI uncovered the operation, they swiftly froze assets worth ₹12.58 crores belonging to all eight individuals—a sum far greater than the ₹4.82 crores in illegal gains. Regulators often do this to prevent money from being moved or hidden during an investigation. SEBI also banned the individuals from trading, ordered them to deposit their illegal profits into an escrow account, and gave them 21 days to respond to the charges. Additionally, banks and depositories were instructed to block any movement of funds or shares without SEBI’s approval.

Beyond the immediate fraud, this case raises serious concerns about market surveillance. For five years, the scheme operated unnoticed, with countless suspicious calls from a regulated dealing desk and trades that mirrored Gagandeep’s almost exactly. It begs the question: how many similar operations are still flying under the radar? And are existing monitoring mechanisms for dealer communications strong enough?

While the headlines focus on the illegal profits made by these eight individuals, the bigger issue is the vulnerability it exposes in the system. This case is a stark reminder that even one major front-running scandal can reveal deeper structural weaknesses in market oversight.

The rise of risky loans, the fall of savings

The next story, centered around banking and finance, has two parts. Both parts explore key challenges in the banking sector that are important for us to understand as investors and market observers. The first part focuses on the rising stress in unsecured retail loans, particularly in microfinance, and the second part highlights a growing challenge on the deposit side of banking.

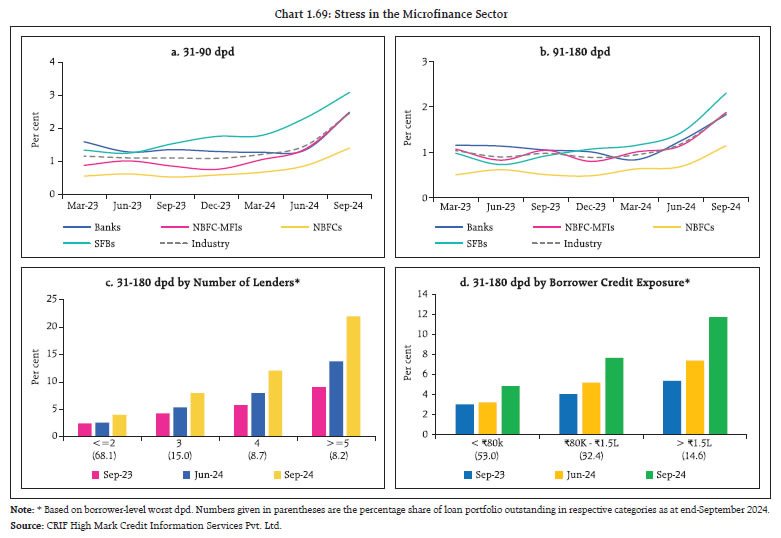

Let’s start with the lending side. Recently, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) raised concerns about increasing defaults in unsecured loans, especially in the microfinance segment. This was detailed in the RBI’s Financial Stability Report published in December 2024. The report revealed that loans overdue by 31 to 180 days surged from 2.15% to 4.30% in just the first half of the 2024-25 financial year. Borrowers with multiple loans or high debt levels were found to be particularly at risk of default. Over the past three years, the percentage of borrowers with loans from four or more lenders rose from 3.6% to 5.8%, signaling a worrying trend of over-leveraging that makes it harder for them to keep up with repayments.

Recent quarterly results from banks and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) have confirmed these concerns. Many have reported a rise in defaults, while growth in microfinance loans has slowed. Take IDFC First Bank as an example. While the bank’s overall performance this quarter wasn’t bad, its microfinance portfolio stood out as a weak spot. A significant portion of its bad loans—referred to as “slippages”—came from microfinance. From April to December, the bank had to provision 8% of its total microfinance loans for potential losses, compared to just 1.7% for other loan categories. Non-Performing Assets (NPAs) in its microfinance portfolio also jumped from 2.5% last quarter to 4.5% this quarter, underscoring the mounting stress in this segment.

Kotak Mahindra Bank is also feeling some heat in microfinance. Although Kotak has slightly reduced its exposure to retail microcredit loans and has years of experience running microfinance businesses (like BSS Microfinance), management has hinted at strain in this area. As a result, the bank is shifting its focus to safer loan categories, such as home loans and corporate loans, to minimize risk and stabilize profitability.

ICICI Bank, on the other hand, is managing better. Its growth remains strong, and its bad loans are relatively low. The bank’s Gross NPA ratio has improved from 2.3% a year ago to 1.96% this quarter. While there has been a slight uptick in bad loans in the retail and rural segments, these numbers are still below the bank’s overall average, suggesting that retail stress isn’t significantly dragging down its performance.

HDFC Bank, following its reverse merger a couple of years ago, is also seeing a small rise in NPAs. Given the bank’s massive scale, even a minor increase is worth watching. Its Commercial and Rural Banking (CRB) segment, which caters to smaller businesses and marginal farmers, saw NPAs rise from 1.8% to 2.0% in just a few months. This signals that even large banks like HDFC aren’t entirely insulated from the pressures in microfinance.

Outside traditional banks, we have microfinance-focused lenders like Spandana Sphoorty. The company’s recent numbers showed a sharp drop in new loans and a significant jump in bad loans. Its Net Performing Assets (NPAs) rose from 1.61% to 4.85%, highlighting that more customers are struggling to repay.

Shifting to the second part of the story—deposits—there’s another challenge brewing. Banks rely on deposits to fund their loans, but the dynamics of deposit growth are changing. The RBI’s Deputy Governor recently flagged concerns about this shift, noting that deposits are often short-term, while loans are typically long-term. This mismatch can create problems if too many depositors demand their money back at once.

As of the 2024 financial year, Indian banks held deposits worth ₹217 lakh crore, accounting for 77% of their total liabilities. Deposits generally fall into two categories: CASA (Current Account and Savings Account) deposits and term deposits. CASA deposits, which are stable and cost-effective, come from individuals and small businesses. Term deposits, on the other hand, offer higher interest rates and are often preferred by large institutional clients. Recently, the share of CASA deposits has been shrinking, while term deposits have been growing. This shift puts pressure on banks because they have to pay higher interest on term deposits, which squeezes their margins.

Kotak Mahindra Bank, once known for its strong CASA deposit base, has seen its CASA ratio decline, which has negatively impacted its net interest margin (NIM). NIM is the difference between the interest a bank earns on loans and what it pays on deposits. To maintain profitability, banks may have to raise loan interest rates, but that comes with its own risks.

Combining these two challenges, it’s clear that banks are walking a fine line. On one hand, they’re grappling with rising defaults in unsecured loans, particularly in microfinance. On the other hand, they’re dealing with a shift in deposit dynamics that’s driving up costs. To navigate this tricky environment, banks are focusing on safer loans, like home loans and corporate credit, while working to attract more CASA deposits to reduce funding costs.

The ability to adapt quickly and manage risk will be key to determining which banks come out on top. Some may handle these challenges well, but others could struggle with rising defaults or shrinking margins. For investors and market watchers, the banking sector remains a critical space to monitor. At its core, it’s about how banks manage the delicate balance between lending and funding—two sides of the equation that must work together to ensure profitability and stability.

Tidbits

Tata Steel reported a 36.37% YoY decline in consolidated net profit to ₹326.64 crore, driven by subdued global steel prices and challenges in international operations.

The JSW Group has announced its entry into copper mining by securing a ₹2,600 crore mine operator and developer (MDO) contract for two copper blocks in Jharkhand. With an ore capacity of 3 million tonnes per annum (mtpa), the mines are expected to be operational by H2FY27.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has announced a liquidity injection of ₹1.5 Lakh Cr. to address a record deficit of over ₹3 Lakh Cr. in the banking system. This includes ₹60,000 crore through Open Market Operations (OMOs) in three tranches, a ₹50,000 crore Variable Rate Repo (VRR) auction on February 7, and a $5 billion dollar-rupee swap auction on January 31. The measures aim to stabilize the rupee, under pressure due to foreign portfolio outflows, and support credit demand.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Bhuvan and Kashish

🌱One thing we learned today

Every day, each team member shares something they've learned, not limited to finance. It's our way of trying to be a little less dumb every day. Check it out here

This website won't have a newsletter. However, if you want to be notified about new posts, you can subscribe to the site's RSS feed and read it on apps like Feedly. Even the Substack app supports external RSS feeds and you can read One Thing We Learned Today along with all your other newsletters.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉 Join the discussion on today’s edition here.

any updates on the book club ?

Summary -

1. Current Indian stock market need better structural regulatory measure, to save it from front running scams or any other type of vulnerability. (May be taking help of machine learning to identify scam related pattern can reduce or prevent such scams.)

2. Indian banks need to find ways to reduce their NPAs wrt to microfinance. I wonder why customer not able to repay their loan. (because of inflation or no saving or loosing their purchasing power). Another point, how bank can increase CASA to maintain profitability and stability.