Will UPI Stay Free Forever?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Can our digital payment systems sustain themselves?

The Rupee’s making a come-back!

Can our digital payment systems sustain themselves?

On March 24, 2025, the Payments Council of India (PCI) — a body which represents over 180 digital payment companies, including the likes of PhonePe, Google Pay, Razorpay, BharatPe, and CRED — wrote directly to Prime Minister Narendra Modi. They wanted the government to reconsider an old demand — of removing the “zero Merchant Discount Rate (MDR)” policy currently applied to UPI and RuPay debit card transactions.

If you’ve kept tabs on the payments space, this is probably no surprise to you. You see such demands crop up every once in a while, only to be shot down by the government.

But despite the obvious political friction around this, they keep coming up again. And that should tell you something. Because at stake is the sustainability of our entire digital payments space.

Let’s dive in.

What is MDR?

An ‘MDR’, at its heart, is a fee businesses pay for using a payments network.

See, when you use a shop’s QR code to make a payment, you aren’t somehow teleporting your cash directly to a merchant. Although the payment process (usually) feels effortless, it’s only possible because of a giant, sophisticated, interconnected system.

Behind the nifty little interface you see on your UPI app screen, the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) has stitched together an entire ecosystem of financial entities. It links together bank accounts, payment apps, and layers of infrastructure — all of which need to come together for your money to move to someone else.

Every time you hit ‘send,’ you kick off a series of events over the next few milliseconds. Your UPI app talks to your bank. Your bank checks if you have enough balance. NPCI steps in to route the request. The receiver’s bank gets the signal, confirms the credit, and the app shows ‘Payment Successful.’ All of this unfolds instantly. While you see a giant green tick on your screen, what you don’t see is a chain of financial institutions clicking together perfectly.

Something similar happens when you use a debit card as well.

Naturally, running this system isn’t cheap. Everyone involved incurs substantial costs, from building the necessary digital rails, to combating fraud, to ensuring server uptime, to innovating and scaling their parts of the system.

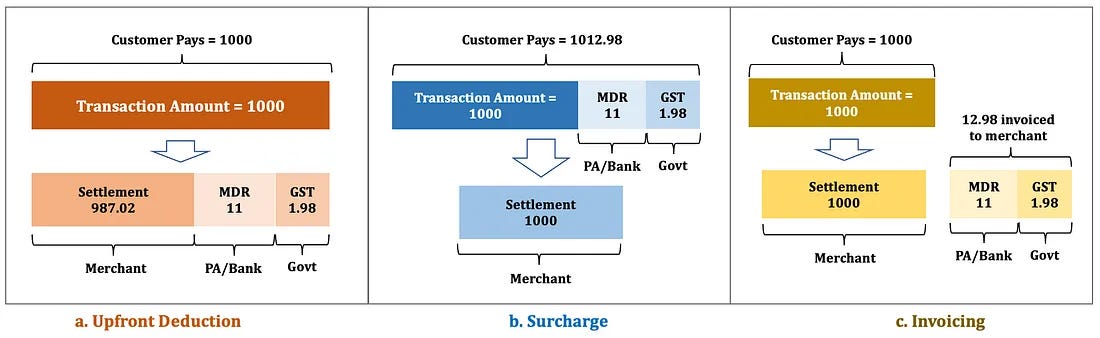

Where do you get the money for any of this? In theory, you could ask those who benefit the most from that payment network to foot the bill. Merchants are a good bet — after all, since so much money is routed to them through these networks, they’re major beneficiaries of this system. You could also charge their customers, or make them split the bill between themselves.

Only, you can’t charge anyone, at least as things stand.

The introduction of zero MDR

When the NPCI first launched the UPI in 2016, an MDR was part of the system. Merchants paid MDR, thus indirectly supporting these backend costs and helping the ecosystem grow.

The government, however, considered this fee to be a problem. It made people reluctant to take to the new system. At first, the government tried subsidising these fees for merchants.

But in January 2020, things shifted dramatically. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced that MDR charges on UPI and RuPay card transactions would go down to zero.

From the government’s perspective, this policy was key to the success of its broader Digital India objectives. The government wanted more businesses — especially small businesses — to adopt its new payment systems. That was the only way people would embrace these systems. And that was only possible if merchants didn’t have to pay anything extra for these new payment systems.

Frankly, it worked. Without extra fees, merchants of all sizes could easily afford and embrace digital payments. Many enthusiastically embraced UPI, rapidly expanding the reach and scope of the systems. Alongside came a surge in the adoption of Quick Response (QR) code-based payment solutions. Unlike traditional card-swiping machines (or POS terminals), QR-based systems were cost-effective, and required minimal infrastructure. Suddenly, the barriers to providing digital payments solutions had dropped massively.

This had various knock-on effects. Millions of people shifted to formal banking systems, particularly in rural and semi-urban areas. Merchants that previously operated entirely in cash could now maintain proper digital financial records. These digital records, in turn, created a paper trail behind their businesses, and helped merchants secure formal credit from banks — who were much more willing to lend against verifiable transaction histories.

As merchants took to UPI, so did consumers. UPI quickly became the most accessible and convenient payment method out there, at least in larger cities.

You’ve probably seen this in how you pay for most things, but here are some graphs to drive home the point:

But although removing the MDR helped with boosting UPI adoption, running the system hadn’t gotten any cheaper. It had, instead, eliminated a critical revenue stream for banks and payment providers.

And with that, these companies argued, the sustainability of the system had become a significant concern.

Yet, the Other Side of the Coin: Sustainability Concerns

Even though the elimination of the MDR had granted merchants immediate savings, industry stakeholders were unhappy. After all, they found themselves subsidising India’s digital payments system, for little reward.

As an article from Ikigai Law notes, without money coming in from MDR, over the long run, you could actually see investments in digital payment systems go down. After all, these revenues are the main incentive banks have to invest in digital payments.

For whose sake are they bearing those costs? Ikigai Law argues that the biggest beneficiaries of a zero MDR aren’t small businesses, but large businesses that are already capable of absorbing these fees easily. Ironically, the small merchants who ought to benefit didn’t really see much practical advantage from the policy. Their low transaction volumes and ticket sizes mean that they’d pay very little MDR anyway.

If anything, the policy has distorted market incentives, which has perverse effects. Without a legitimate source of revenue from UPI transactions, instead, banks and payment providers began levying opaque, indirect charges. They also found ways to cross-subsidise the service: by selling data, upselling other products, or selling advertisement space. What could have been a straightforward business essentially became a lot more murky and opaque.

Of course, it’s not as though the government was blind to these issues. It introduced several incentive schemes to (partially) cushion the industry's revenue losses. The budget for these schemes steadily increased—from ₹1,389 crore in FY21-22, to ₹2,210 crore the following year, and ₹3,631 crore in FY23-24. In FY24-25, the government allocated ₹1,500 crore specifically for incentivizing small-value UPI transactions up to ₹2,000.

Was this enough, though? The payments industry thinks otherwise. It argues that these incentives cover only a tiny fraction of the actual annual cost to maintain and expand UPI infrastructure — which it estimates at around ₹10,000 crore per year. (We haven’t seen the workings behind that figure, however. Take it with a pinch of salt.)

Reintroducing MDR raises several significant questions:

That’s why the Payments Council of India has written its latest letter to the Prime Minister. It says that the situation is reaching a tipping point. 90% of India's 6 crore merchants are small (with annual turnovers below ₹20 lakh). They propose excluding this cohort, and reintroducing a modest MDR fee of 0.3% for large merchants (those with turnover above ₹20 lakh). This, they say, is a fraction compared to MDR rates charged for other payment methods such as credit cards (around 2%) and prepaid instruments (about 1.5%).

If the government agrees, what might happen? Here are a few things to think about:

What would adding MDR back to UPI mean for users? Would merchants pass these costs onto consumers, sending prices higher and making digital transactions less attractive? Would UPI become less appealing? And could this undermine the significant progress India has achieved in financial inclusion?

Despite UPI's zero MDR policy, at least for some types of transactions, merchants already pay fees to payment companies. These are often labeled as service or convenience charges. Would officially reintroducing MDR enhance transparency, or merely add another layer of costs for merchants and consumers?

But the most fundamental question is this: Can systems like the UPI sustainably scale without MDR, or is a modest fee essential for maintaining its long-term success?

The Rupee’s making a come-back!

The rupee’s been on a bit of a ride lately. Just a few weeks ago, the Rupee seemed to be bleeding its power, with the USD/INR up near 87.40. Fast forward to today, and it’s slid all the way down to under 86. That’s a big move for currency markets. After slipping for a long time, the Rupee essentially made a sudden about-turn.

So, what just happened? Is this a turning point? Is the worst over for the Rupee? Or is this just some temporary respite.

Wait… why do I care?

Before we jump into the details, let's talk about why currency movements matter in the first place. Think about it like this — when your country's currency strengthens, your money can essentially do more when you’re buying foreign goods. That imported iPhone? Cheaper. Planning a vacation abroad? Your hotel stays cost less.

But there's a flip side, of course. Your exports become more expensive for foreigners to buy. If you’re running an export-driven business, that can hurt.

When your currency weakens, the opposite happens. Imports get more expensive, potentially driving up inflation, but your exports become more attractive to foreign buyers.

So basically, every currency movement — regardless of the direction — presents a trade-off. Some people benefit, some are left worse off. It's this delicate balance that makes currency movements so crucial for economies, especially for a rapidly developing country like India that's trying to boost both domestic consumption and exports.

What’s happening with the Rupee

The investment bank MUFG just published a great analysis on the Indian Rupee, with a breakdown into what's powering our currency movements.

Let’s rewind a bit. For months, the rupee was dragging its feet. Growth was underwhelming. Inflation was sticky. The trade deficit looked worrying. Foreign investors were either sitting on their hands or quietly pulling money out. And on top of all that, the Reserve Bank of India had taken a call to stay away from the FX market after a long time, letting the rupee find its own path instead of swooping in to smooth things out. In that environment, MUFG expected to see a weaker rupee.

But then came March. And suddenly, the rupee got its groove back.

What's driving this surprising strength? According to MUFG's analysis, it's a combination of both global and local factors.

The initial lift came from global factors. The euro, of all things, grew unexpectedly strong — mostly thanks to Germany opening up its famously tight purse strings and launching a fiscal stimulus. As the Euro strengthened, the Dollar began to weaken, and gave emerging market currencies like the Rupee some room to breathe.

But the bigger surprise came from domestic factors. The Rupee has actually outperformed other Asian currencies in March, which tells us there are India-specific factors at play.

First, India's trade picture improved significantly. Our services exports held strong, while gold and oil imports dropped, narrowing our goods trade deficit.

In fact, our combined goods and services trade balance actually turned positive in February — something quite rare for India, which typically runs deficits.

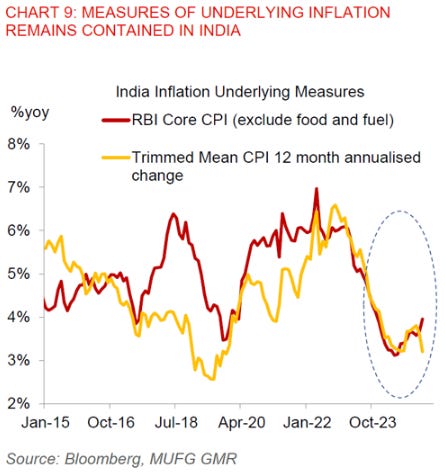

But there was more. Inflation surprised everyone on the downside, coming in lower than expected in February.

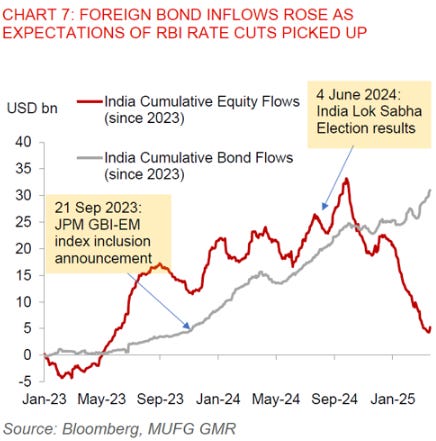

This increased expectations that the Reserve Bank of India could start cutting interest rates. Foreign investors began nibbling at Indian bonds again, providing further support for the rupee. There was also a short-term technical boost from global equity index rebalancing—an unglamorous but significant factor that brought in over a billion dollars toward the end of March.

There was also a short-term boost from global equity index rebalancing — an unglamorous but significant factor that brought in over a billion dollars toward the end of March.

What comes next

Here's where it gets interesting. Despite this recent strength, MUFG believes the Rupee could grow weaker going forward. It’s no longer bearish on the INR, but they’ve gone “neutral.” That doesn’t mean they’re bullish.

They've revised their year-end forecast to 87.50 rupees per dollar. That’s actually slightly stronger than their previous forecast of 88.50, but still implies a meaningful depreciation from current levels.

So what’s the reason for the caution?

Trump tariffs

The first big concern is Trump. Or rather, the looming threat of reciprocal tariffs under a Trump 2.0 administration, which it thinks the markets are significantly underpricing. If he follows through on his threats, India could be hit hard. According to MUFG’s calculations, if Trump uses a blunt country-level approach, tariffs on Indian exports could jump from 2.8 percent to 9.5 percent. If he gets more surgical and goes product by product, they could shoot up to 15 percent. That second scenario is unlikely — it’s messy, complex, and hard to enforce — but even the first one would be painful.

While India is less export-dependent than many Asian economies, the US is still a major trading partner. Exports to the US directly make up about 2% of India’s GDP. If you count value-added exports, that figure goes up to around 4%. Tariffs, if they do come in, could do serious damage.

What makes it worse is that India also stands out for a bunch of non-tariff irritants. Things like digital taxes, regulatory quirks, content requirements, and subsidies have all drawn attention in past US trade reports. While India is quietly trying to fix some of these — there’s been talk of lowering tariffs on specific goods and rolling back digital taxes — it’s not clear whether those moves will be enough to avoid a confrontation.

MUFG's base case is that India and the US will likely sign a trade deal by the end of the year, which could help us out in the long run. In the meanwhile, they expect higher import tariffs from the US on Indian goods starting in April.

Sub-par growth expectations

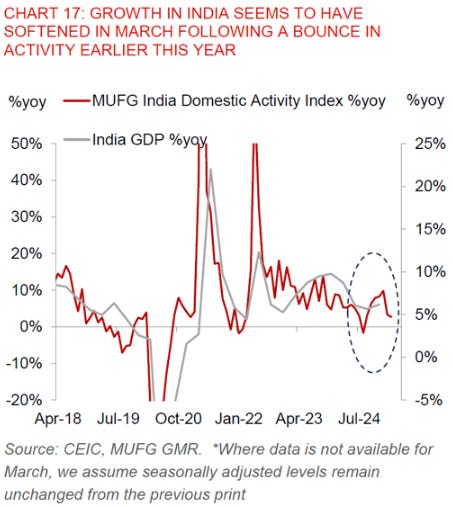

The second issue is India’s growth outlook — which isn’t bad, but it isn’t great either. MUFG thinks the market is being a bit too optimistic. MUFG thinks India’s economic activity softened in March, following a bounce in January that was possibly boosted by the Kumbh Mela.

Growth remains somewhat soft at around 6-6.5%, which is below India's previous 7-8% growth rates. There are some deep issues at play. The RBI’s earlier steps to rein in risky lending are starting to bite, public infrastructure spending has slowed, and the credit cycle is showing signs of fatigue.

RBI’s going to buy some dollars

The third reason MUFG thinks the Rupee might fall is the Reserve Bank itself. The RBI has been unusually quiet on the FX front lately, letting the market do its thing. But there’s a strong case for it to start rebuilding its foreign exchange reserves soon.

There’s more — right now, the RBI is sitting on a net short position of $77 billion in its forward book. At some point, it’s going to want to unwind that—meaning it’ll need to buy dollars. And when the RBI buys dollars, it pushes USD/INR up.

The silver lining

It’s not all doom-and-gloom, though. There’s some good news too. For one, the government recently announced income tax cuts, which should support consumption.

Moreover, MUFG expects the RBI to cut rates three times this year—once each in April, August, and December—bringing the repo rate down to 5.50 percent by year-end. To help things, India’s inflation is coming down. Core inflation is stable, food price spikes have been contained so far, and heatwave concerns haven’t yet materialized in the data. That gives the RBI the room it needs to cut rates without panicking about price stability.

This should help boost India’s growth. (Though it will also reduce interest rate differentials, which could pull some capital out and weaken the rupee again.)

They also expect the RBI to ease macroprudential restrictions further and push out more liquidity — which will bring down the economy’s effective interest rates. This could help support our growth, in spite of all the headwinds we face.

Looking a bit further out, there’s one long-term development that might be deeply important in the long run: India is actively trying to diversify its trade relationships. We’re talking to the EU, the UK, and New Zealand. A US-India trade deal might even materialize by year-end. If we can pull this off, it would reduce our vulnerability to sudden tariff shocks and make our exports more resilient.

So, where is the Rupee headed?

The rupee’s recent rally has been driven by a rare alignment of positive factors: a weaker dollar, stronger services exports, lower imports, and a surprisingly tame inflation print. But under the surface, there are still major risks. Tariffs, slower growth, and central bank dollar buying could all reverse the trend. MUFG’s forecast reflects this tension: a gradual drift upward to 87.50 by December, not a crash, but not a celebration either.

In short: the worst might be over, but the rupee’s story is far from settled.

Tidbits

JSW Steel has become the world’s most valuable steelmaker with a market capitalisation of $30.31 billion, overtaking Nucor Corporation ($29.4 billion) and ArcelorMittal ($27.14 billion), according to Bloomberg data. Despite reporting lower trailing 12-month revenues of $21.1 billion compared to ArcelorMittal’s $62.4 billion, JSW Steel commands a higher price-to-earnings ratio of 28.5x, versus ArcelorMittal’s 20.3x. The company currently has a production capacity of 35.7 million tonnes per annum (mtpa), including operations in the US, and plans to scale up to 51.5 mtpa by FY31, with 50 mtpa in India. JSW’s stock has risen over 17% since the start of the year, supported by rising steel prices and a proposed 12% safeguard duty on certain steel imports. JSW has also announced a ₹1,676.45 crore share buyback in its Italian subsidiary, Piombino Steel.

Tata Electronics has approached the Gujarat government for an additional 80 acres of land to expand its semiconductor fabrication facility in Dholera. The new land will support housing and infrastructure, including around 3,000 studio apartments for workers, along with a shopping complex, sports arena, and entertainment facilities. This follows the earlier allocation of 20 acres and a letter of support for another 63 acres in future. The ₹91,526 crore project includes a chip fab and supporting infrastructure costing ₹15,710 crore. The facility is expected to create 1,900–2,000 direct jobs and will manufacture chips using 110, 90, 55, 40, and 28 nm technologies. Once operational, the fab will have a capacity of 50 wafer starts per month. It is the only fabrication unit approved under India’s ₹76,000 crore Semiconductor Mission.

Samsung and seven of its Indian executives have been ordered to pay a total of $601 million by Indian authorities for allegedly evading import duties on telecom equipment supplied to Reliance Jio. The demand includes ₹4,460 crore ($520 million) in unpaid taxes and penalties, along with an additional $81 million in fines levied on top executives including the network division’s vice president and CFO. The dispute centers on the classification of "remote radio heads," a key 4G telecom component, which customs officials argue was misrepresented to avoid 10-20% tariffs. The demand represents a substantial chunk of last year’s net profit of $955 million for Samsung in India. The confidential customs order from January 2025 accuses Samsung of knowingly presenting false documents to authorities. The company has said it is reviewing legal options to protect its interests. The case follows a 2021 investigation that involved raids, seizure of documents, and questioning of senior leadership.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Pranav & Bhuvan

📚Join our book club

We've recently started a book club where we meet each week in Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you'd like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Counter 1: Small mechants will pay very little MDR anyway.

Little in comparision to what? Zerodha's profits? While that would be true, a 2-3% MDR on 10-15% net margin business means 20% of what merchant could take home. Even at 0.3% for someone earning 20,000 that is a cost of 600 - one less pizza treat for a family every month!

Counter 2: Bigger companies have more capacity to absorb.

The public market pressure will make big corp's knees weak. Instead of more capacity to absorb, focus should be on more bargaining power against consumers who will ultimately bear the brunt. Manufacturers can easily include 2% in pricing but small traders who have little say in MRP & margins will lose out.

Also, for a fast forward we can look at countries ahead of us. Merchants push it onto customers. "2% extra charges on cards", it reads at most mom-pop shops in London.

Which discourages digital payments.

Unpopular Opinion:

The cost of digital payments will not come from directly charging for them at either end, it will come from second order effects of digital payments.

Second Order Effects:

1. Not losing out on purchase occasion when customer is not carrying cash.

Increased spending > Increased business > more tax collection

2. Leaks prevention in govt welfare schemes.

3. (For Banks) Paper Trail to access credit risk > increased lending > increased profits.

4. Lower remittance charges (digital payments diplomacy) > more net net money in India.

Punch Line: Free Digital Payments lauch a virtuos cycle of cash flow.

P.S., Nerdy take for fellow economists: Digital payments can in theory help solve fishers identity because we can finally see the velocity of cash!