Why your vegetables matter more than you think

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

How fruits and vegetables shaped Indian farming

Behind India's Mutual Fund Boom

How fruits and vegetables shaped Indian farming

Both of today’s stories come from the latest RBI bulletin.

The first story uncovers an interesting transformation happening quietly across India's farmlands. While headlines always focus on farmer distress and export restrictions, the RBI paper on "Horticultural Diversification" reveals a more nuanced story about how Indian agriculture has grown over the past three decades.

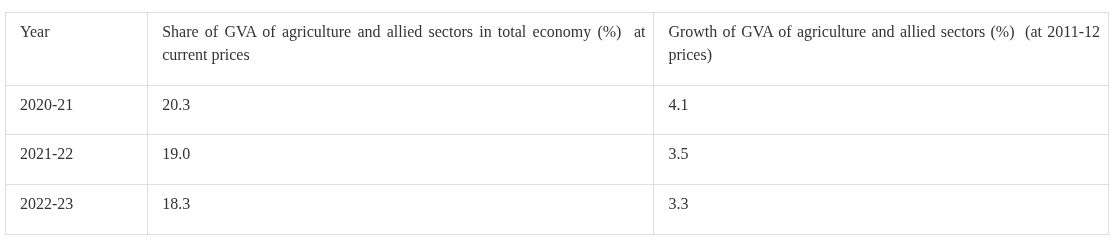

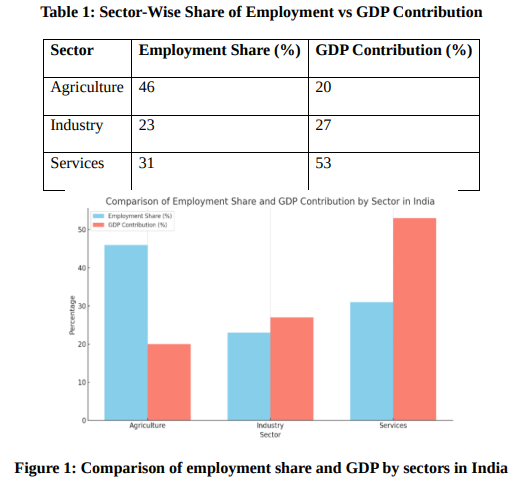

This matters because agriculture remains central to India's economy in ways that GDP numbers alone don't capture. While farming now contributes less than one-fifth of the country's gross domestic product, it still employs 46.1 percent of India's workforce.

That’s almost half the population. Understanding how this sector evolves affects nearly half a billion people and shapes food security for 1.4 billion Indians.

The RBI study examines agricultural growth from 1992-93 to 2022-23, breaking it down into four key drivers: expanding farmland, improving yields, price changes, and crop diversification. The standout finding is that India's farm growth came primarily from two sources: better productivity per acre and a strategic shift toward horticulture—which includes fruits, vegetables, spices, and aromatic plants.

Unlike cereal farming that focuses on staples like wheat and rice, horticulture emphasizes crops that typically earn more money per acre but require different skills and storage capacity.

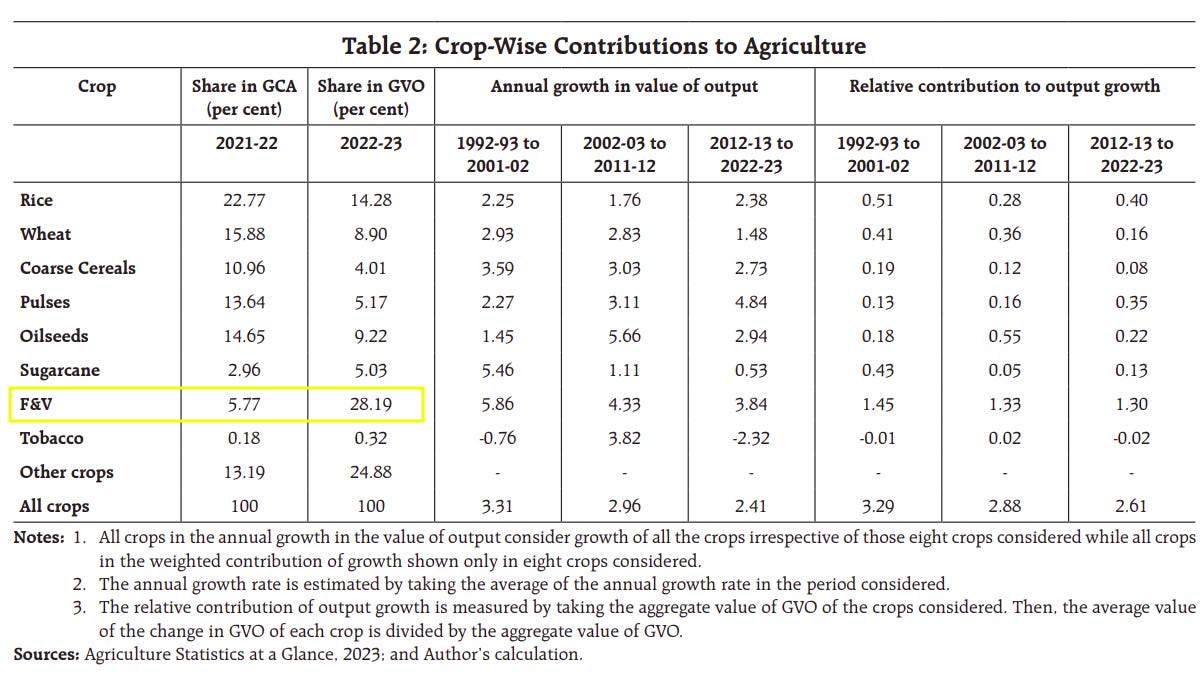

The paper reveals a striking paradox: fruits and vegetables occupy just 5.8% of India's cropland but generate 28.2% of the total farm output value.

This small slice of agricultural land is doing disproportionately heavy lifting in supporting rural incomes. This made us curious about a space we haven’t really looked at before.

Let’s dive in.

India’s agriculture through the decades

To understand today's horticultural shift, we need to first understand the structure of Indian farming.

In the 1960s, India wanted to turn from a food aid recipient to a net food exporter. So, we pursued a Green Revolution to make us self-sufficient in food for once and for all, by specifically focusing on increasing wheat and rice production.

The government prioritized this through subsidies, procurement systems, and research investments that prioritized staple grains. The Food Corporation of India guaranteed purchases of wheat and rice at minimum support prices, creating a safety net that made these crops attractive to farmers. Power subsidies encouraged groundwater pumping for irrigation, while fertilizer subsidies lowered input costs.

This system boosted our food security by leaps and bounds. But it also created a path dependence. Farmers stuck with wheat and rice because they offered predictable returns, even as Indian diets began changing with rising incomes and urbanization.

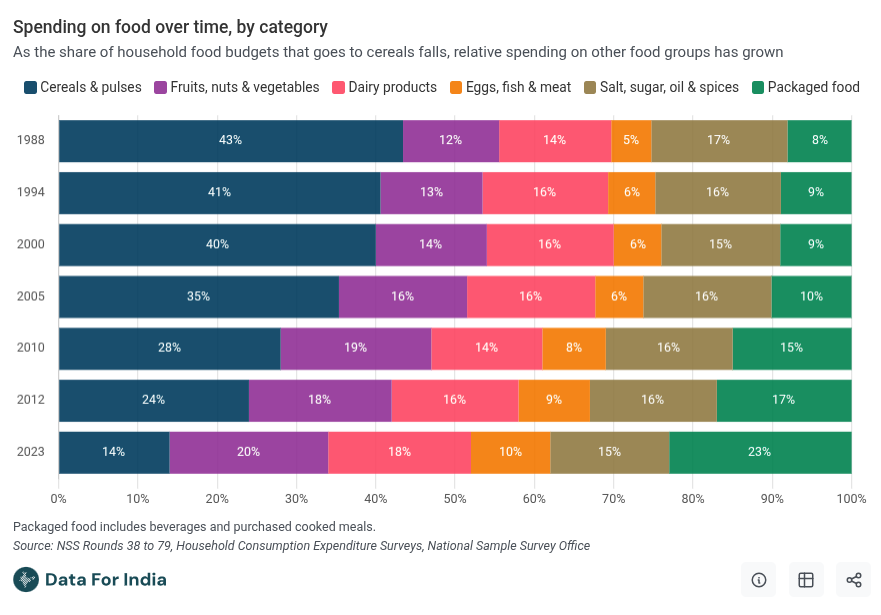

The RBI study shows how this began shifting in the 1990s. The liberalization of the economy, changing consumer preferences, and policy initiatives like establishing a dedicated Ministry of Food Processing Industries encouraged farmers to experiment with new crops. Rising incomes meant families started spending more on fruits and vegetables and less on basic cereals.

Data from household consumption surveys illustrate this dietary transition clearly. The share of fruits & vegetables in total food spending rose from 14% percent in the 2000s to 20% percent in 2023.

Meanwhile, spending on cereals declined sharply across the same period from 40% in 2000 to 14% in 2023. Indian families were literally voting with their wallets for more diverse diets, and farmers began responding to these market signals.

What the report finds

The RBI analysis reveals something counterintuitive about who's leading this horticultural shift. One might assume that high-value crops would be driven by larger, capital-rich farmers. But the data tells a different, more nuanced story.

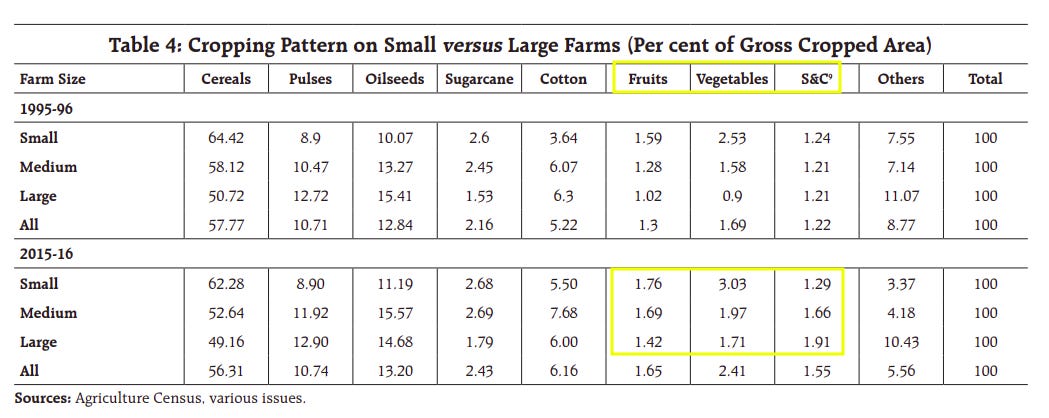

Small farmers—those with less than two hectares of land—actually dedicate a larger share of their plots to horticulture compared to their larger counterparts. In 2015-16, small farmers allocated 6.08 percent of their land to fruits and vegetables, versus 5.04 percent for large farmers and 5.32 percent for medium-sized operations.

his pattern makes economic sense when you consider the different crops involved. Small farmers gravitate toward vegetables like onions, tomatoes, and brinjal that offer quick returns and require not much more beyond intensive labor. These crops can be harvested within months, providing faster cash flows crucial for households operating on tight margins.

Large farmers, by contrast, tend toward fruits and certain spices that demand higher upfront investment but take longer to mature. Mango trees require 3-5 years before bearing fruit, while onions can be harvested in about six months. The capital requirements and payback periods align with different farmer circumstances.

However, there’s more to this story. This shift is, at least, partly driven by a structural problem in Indian agriculture — that it’s too dependent on small, often ill-equipped farmers. And their landholdings are shrinking rapidly — the average farm size has decreased from 2.28 hectares in 1970-71 to just 1.08 hectares in 2015-16, making efficient production increasingly challenging.

On top of small, inefficient landholdings, debt distress remains a persistent problem. The average debt load per agricultural household exceeds ₹70,000—at least seven times their average monthly income. Half of India's farmers lack access to formal financing, forcing them to be at the mercy of informal lenders who charge exorbitant interest rates.

Within these constraints, horticulture offers a pathway forward for small farmers. The crops they are adopting—vegetables, fruits, spices—align well with their resource constraints while offering more output per land. The study finds that small farmers increased their horticultural area share consistently across two decades, from 1995-96 to 2015-16.

What really drove farm expansion

The RBI paper also identifies what actually powered agricultural expansion over three decades. It reveals not just horticulture’s role, but also how Indian agriculture as a whole has progressed.

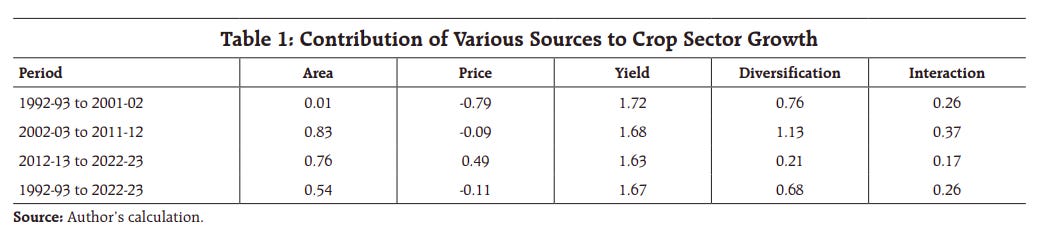

Across 1992-93 to 2022-23, improvements in crop yield contributed 1.67 percentage points annually to agricultural growth, making it the single largest driver. Crop diversification, i.e. primarily the shift toward horticulture added another 0.68 percentage points yearly. Area expansion contributed just 0.54 percentage points, while price effects were essentially neutral.

This means India's farm success wasn't primarily about cultivating more land or benefiting from higher food prices. Instead, it came from using existing land more productively and growing crops that markets increasingly valued. However, these average figures don’t fully reveal how the contribution of each factor changed over time.

In the first decade studied (1992-93 to 2001-02), yield improvements and diversification drove most growth while farmers faced unfavorable prices. The second period (2002-03 to 2011-12) saw diversification become even more important, contributing 1.13 percentage points to annual growth. The most recent decade (2012-13 to 2022-23) was the most balanced, with all four factors—area, yield, prices, and diversification—contributing positively.

The RBI also looks at the growth contributions of each crop to Indian agriculture, and within that, horticulture stands out. Fruits and vegetables consistently showed the highest growth rates across time, making up 1.30-1.45 percentage points annually. Without this horticultural expansion, India's farm sector growth would have been noticeably slower.

The Triple Challenge

Despite horticultural success, the RBI study identifies three persistent challenges that constrain further expansion and farmer welfare.

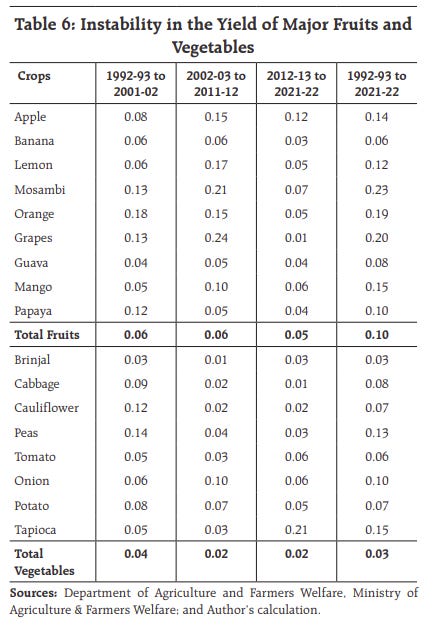

Unpredictable yields

The yields from fruit crops (like mango, grapes, citrus, and litchi) are a lot more volatile and prone to swings compared to vegetables. This is due to weather conditions, pest attacks, and other factors. Some fruits like grapes and sapota actually saw declining yields over certain periods.

Price Volatility

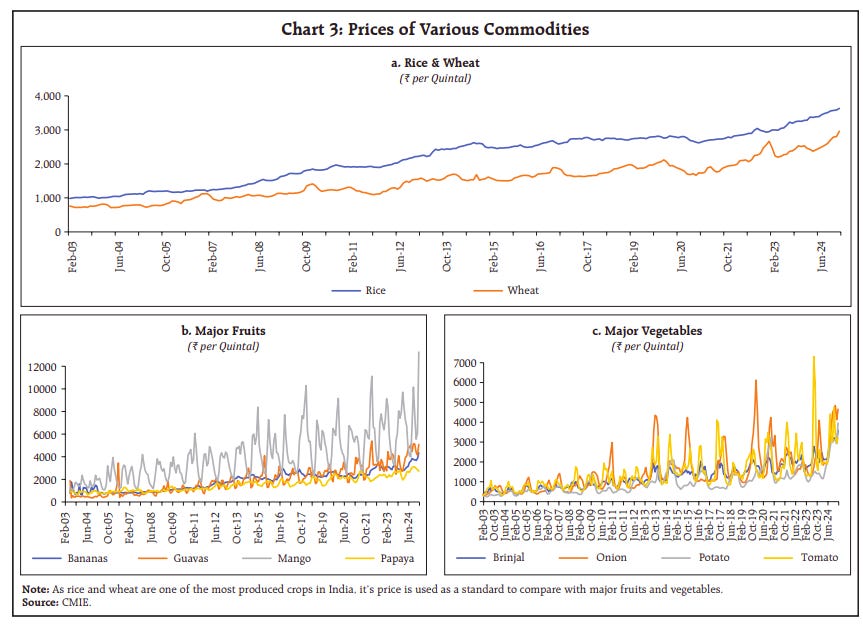

Unpredictable yields naturally show up in unpredictable prices, and fruits & vegetables go through extreme price swings. Tomatoes can fluctuate from ₹2 to ₹100 per kg within short periods, creating planning nightmares for farmers.

This volatility also reveals why farmers might prefer wheat and rice over horticulture, despite lower-per acre returns compared to horticulture — wheat and rice benefit from guaranteed government procurement at minimum support prices. The study documents how rice and wheat prices have remained relatively stable and shown upward trends, thanks to state procurement.

The costs of having less storage

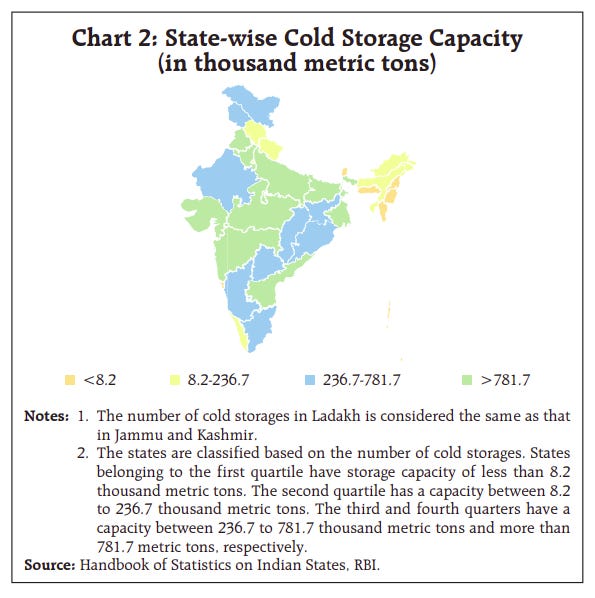

Meanwhile, there’s also our lack of cold storage facilities, due to which India wastes a whopping ₹1.5 trillion worth of agricultural produce annually. Fruits and vegetables bear most of this brunt. A huge economic loss by any means.

Even the distribution of existing storage facilities is very unbalanced. Four states—Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Gujarat, and Punjab—account for 71 percent of our total capacity (nearly 40 million metric tonnes).

The technical challenge extends beyond mere capacity. Different fruits and vegetables require specific temperature and humidity conditions, making multi-commodity storage technically complex and expensive to operate. In fact, 75 percent of existing cold storage is dedicated to just one crop—potatoes. They are not suited to other foods which spoil quickly.

Policy Implications

The RBI study's findings have significant policy implications. If horticulture is indeed driving agricultural growth and benefiting small farmers, government policies need to adapt accordingly. Currently, most subsidies and support systems remain oriented toward wheat and rice production.

The paper suggests several areas requiring attention. Stronger linkages between farmers and urban consumers could accelerate growth, as could better connections to export markets. Intercropping i.e. mixing horticulture with traditional crops could improve yields while enhancing soil health and farmer incomes. The growth of agro-processing industries could unlock higher export potential while reducing post-harvest losses.

Government initiatives are already underway attempting to address the gaps in horticulture. The Agriculture Infrastructure Fund, established in 2020, has already sanctioned over 48,000 storage projects adding 94 million tonnes of capacity. To stabilize horticulture prices, the government launched Operation Greens in 2018, initially targeting tomato, onion, and potato. The state also launched the Horticulture Cluster Development program in 2021 — which aims to create 55 market-driven competitive hubs for horticulture.

The execution of these policies — as well as structural reforms in Indian farming as a whole — will decide how successfully India shifts to horticulture. So far, the shift has been driven out of a necessity, and it certainly represents a positive adaptation. But to keep this shift resilient, a lot more ground work needs to be done.

Behind India's Mutual Fund Boom

Just over a decade ago, mutual funds represented less than 1% of household savings in India. Today? They've captured 6% and are growing fast. In a decade, an entire nation has rewired its relationship with money and risk.

The RBI Bulletin contains a comprehensive section on equity mutual funds, and the findings reveal something remarkable: India is experiencing a "savings revolution." And it isn't just happening in Mumbai or Delhi. It's spreading to small towns, attracting women investors, and creating new patterns of wealth building that could reshape the entire economy.

Let’s dive into it.

The scale of transformation

First, let's talk about the sheer scale of what's happening.

The mutual fund industry's assets under management (AUM) have grown from ₹6.1 lakh crores in 2010 to over ₹65.7 lakh crores by March 2025. That's more than a 10x increase in just 15 years, growing at 17.1% annually.

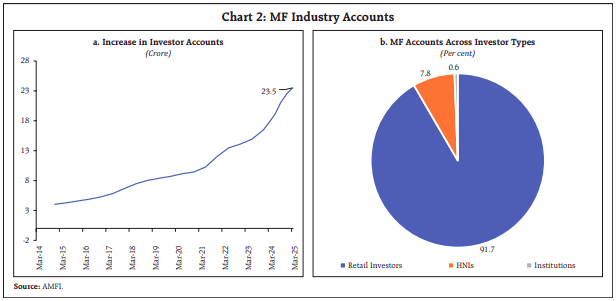

This flush of funds has been accompanied by more people registering themselves as investors. Investor accounts have jumped from around 4 crores in 2014 to 23.5 crores in 2025 — nearly 6x more investors in just over a decade. The number of unique mutual fund investors has now crossed the 5 crore mark, making this one of the largest retail investment migrations in Indian financial history. And here's the kicker: 91.7% of these accounts belong to retail investors – regular folks, not big institutions or wealthy individuals.

And this is no flash in the pan. The mutual fund trend is pretty resilient, which can be seen in how much new money enters these funds every month.

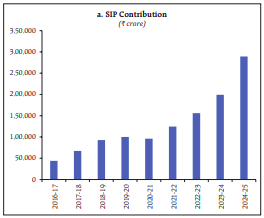

Monthly SIP contributions – investment plans where people invest a fixed amount regularly – have been hitting record highs consistently. By June 2025, monthly SIP inflows crossed the ₹27,000 crore mark despite significant volatility in Indian equity markets due to geopolitical uncertainties. To put this in perspective, the SIP book now has nearly 9.2 crore active accounts, representing one of the largest retail investment programs globally.

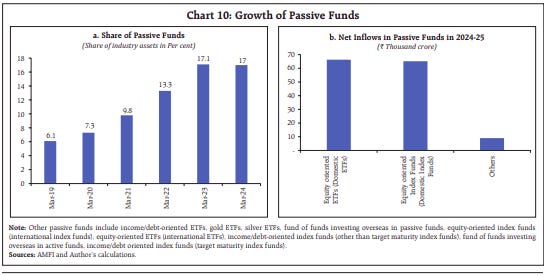

Part of this boom is being driven by passive mutual funds — which simply track an index like Sensex or Nifty, instead of trying to beat it through active stock selection. Passive funds make up 17% of the industry’s assets — up from just 6.1% in March 2019.

During 2024-25 alone, passive funds saw net inflows of 1.4 lakh crores. Many of these passive funds receive their money from institutions like the Employees’ Provident Fund — which holds the “PF” contribution of your salary. Passive funds typically charge much lower fees than actively managed funds since there's no expensive research team trying to pick winning stocks. It’s cheap and effortless to put money in a passive fund.

Here’s one last tidbit on the actual scale and influence of mutual funds: their shareholding in companies listed on the NSE has grown from 3.7% in March 2010 to 10.4% in March 2025.

How is the mutual fund revolution distributed?

What regions and which people are driving the mutual fund boom says quite a bit about India's economic geography and wealth distribution.

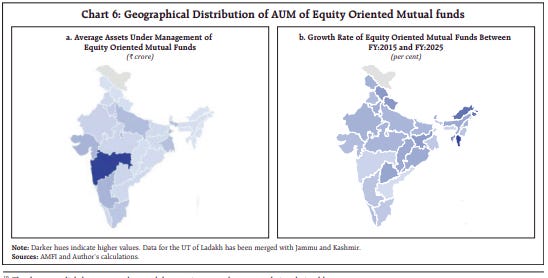

Maharashtra dominates the landscape, accounting for over a quarter of equity mutual fund assets under management. The densely-populated northern and eastern states account for a relatively lower share despite their population size. But a lot of the action is in what the industry calls "B-30" cities – basically, everywhere beyond the top 30 metropolitan areas. These smaller cities are seeing faster growth in new SIP accounts compared to major metros.

But while smaller cities are driving new account growth, their share of actual assets under management remains low. As of end-June 2025, only 18% of the mutual fund industry's assets come from B-30 locations, despite generating most of the new investor accounts.

Why this disparity? Well, it likely comes down to ticket size and income levels. People in smaller towns are starting their investment journey with smaller amounts — maybe a smaller monthly SIP compared to larger amounts in metro cities. But they're starting, and that's the crucial part.

Women's participation is also surging dramatically. Their share in industry assets has grown from 15% in March 2017 to nearly 21% by December 2023. The total assets under management by women investors more than doubled from ₹4.59 lakh crores in March 2019 to ₹11.25 lakh crores in March 2024.

The science behind the flows

So what's actually driving this massive transformation?

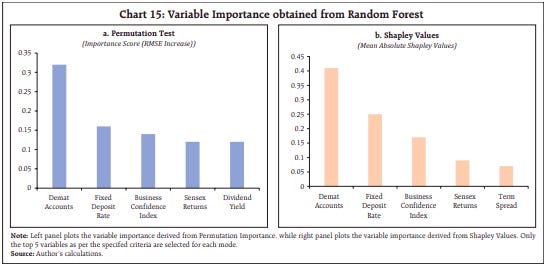

The RBI identified 3 key drivers that most accurately predict future equity mutual fund flows.

First, the explosive growth in demat accounts

This one is self-explanatory. Demat account growth is really a proxy for financial inclusion and the digitization of investing. When more people have easy access to financial markets through demat accounts, it naturally leads to higher mutual fund participation.

Second, how fixed deposit rates influence the switch to alternatives

When traditional safe havens like the traditional fixed deposit offer low returns, people actively search for alternatives.

The fixed deposit rate story is particularly interesting because it shows how Indians are becoming more sophisticated about relative returns. The study points out that Sensex returns have beaten fixed deposit returns in 10 out of the last 15 financial years, with the Sensex delivering a 12% compound annual growth rate compared to 7% for term deposits between 2010-11 and 2024-25.

We also know this because the risky mutual fund is growing ever more popular relative to the good old safe bank deposit. The ratio of mutual fund assets to total deposits has more than doubled from around 10% in 2014 to 23.8% by 2024. For every 100 rupees sitting in bank deposits, there are now about 24 rupees in mutual funds – and this share is growing rapidly. This is a notable shift in how much more risk we’re willing to take.

Third, business confidence

When the overall business environment looks positive, people feel more comfortable taking on equity risk.

The business confidence factor suggests that retail investors are more economically aware than they're often given credit for. They're not just chasing returns blindly – they're actually paying attention to broader economic conditions. And this, in turn, has enabled higher risk appetites.

Patience and risk

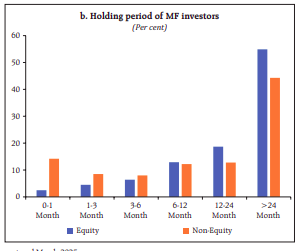

This brings us to a significant behavioral change that drives this revolution: Indian retail investors are showing remarkable patience by parking their money in mutual funds for long holding periods.

Get this: 61% of retail investors hold their equity mutual fund investments for more than 24 months as of March 2025. That number was just 44.9% in March 2023 and 53.3% in March 2024. Each year, more people are choosing to stay invested for the long haul.

Indian investors are maturing beyond the traditional mentality of wanting quick returns or panicking during market volatility. They're not treating mutual funds like a quick trading vehicle – they're using them for genuine long-term wealth creation. What's even more remarkable is that this patience is holding up despite market turbulence. Even during times of unpredictability, the sticky nature of these investments has remained intact.

There's a flip side to all of this that is worth considering: while this long-term orientation is great for wealth building, it also means these investors are taking on more equity risk than previous generations. In essence, a large section of India's middle class has been convinced to embrace market volatility in exchange for potentially higher returns.

For instance, take the issue of small and mid-cap stocks. The RBI finds that mutual fund flows are actually so big now that they are affecting equity market returns, particularly in small and mid-cap segments. But there’s a critical issue: small and mid-cap stocks typically have much lower liquidity than large-cap stocks. When mutual funds need to sell during periods of redemption pressure, it can create significant price movements. The very act of buying or selling in big quantities moves prices, especially in less liquid segments. And common retail investors often bear the brunt of this.

The regulators have recognized this risk. SEBI has now asked mutual funds to put in place appropriate measures to protect investors in small and midcap funds by using tools like moderating inflows, portfolio rebalancing, and ensuring protection in situations where large buy/sell moves are involved.

Moreover, to ensure that mutual funds act in the best interest of their unit-holders, SEBI mandated MFs to vote on resolutions moved by the boards of companies they’ve invested in. MFs now have a say in issues of corporate governance and the capital structure of a company, and they’re increasingly exercising their right to vote. It should, however, be noted that MFs make up a very small chunk of ownership in listed companies for this to have a major impact, yet.

Looking ahead

Millions of Indians are moving from being savers to being investors, from seeking guaranteed returns to accepting market risks for potentially higher rewards.

The mutual fund industry is still relatively small compared to advanced economies, suggesting enormous room for growth. But growth brings responsibilities. As the RBI study notes, these new investors need to understand both the opportunities and the risks they're taking on. And that requires both regulatory measures and efforts to educate new investors.

The question isn't whether this trend will continue – the fundamentals suggest it will. The question is how smoothly this transition happens and whether the systems can evolve sustainably to support millions of new investors making their first foray into equity markets.

Tidbits

We had written about India’s new Online Gaming Bill in a previous edition. It has now forced real-money gaming firms to shut paid formats, triggering mass layoffs. Games24x7 cut 400 jobs, MPL is letting go of 60% of its India staff, and PokerBaazi’s parent laid off nearly half its workforce, as the sector pivots to free-to-play and ad-led models amid collapsing revenues and investor confidence.

Source: The Hindu Business Line

UPI transactions crossed 20 billion for the first time in August 2025, with volumes up 34% year-on-year to ₹24.85 lakh crore. On average, 645 million transactions happened daily, with most high-value payments going towards loans, credit card, and BNPL bills, while groceries and restaurants drove volumes.

Source: The Hindu Business Line

BigBasket CEO Hari Menon is preparing a succession plan as his tenure nears completion, with Tata Group set to bring in a new chief executive. Menon, who co-founded the company in 2011, may move into a mentor role while Tata sharpens BigBasket’s position in the quick commerce battle against Blinkit, Swiggy Instamart, and Zepto.

Source: The Economic Times

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Bhuvan

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Thanks a lot for well written and insightful article. Being a farmer I know the challenges involved for small farmers who tend to grow vegetables for higher yield. But pricing strategy from govt has to improve. The agro forestry is another one area catching momentum specifically for the farmers who hold large parcel of lands - but that would require substantial financial cushion.