Why Venezuelan oil needs Indian refineries

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Will India refine Venezuelan oil?

Are Local Indian Governments Spending Enough?

Will India refine Venezuelan oil?

Three days into 2026, Donald Trump posted something wild — even by his standards.

Early that morning, American special forces landed in Caracas, and captured the Venezuelan President, Nicolás Maduro. A transitional government was sworn in, marking the end of a reign that had lasted for over a decade.

The US offered many justifications for the operation — which we won’t go into. One that stood out, though, was oil. A few days after his raid, Trump announced that Venezuela would turn over millions of barrels of oil to the United States. Shortly afterwards, he claimed that America would control Venezuelan oil for years.

This was an abrupt rupture in policy. Less than a year ago, the United States was threatening countries that bought Venezuelan oil with tariffs. Now, American oil companies are being pressured to step up Venezuelan oil production.

Amidst all this, India is in an interesting spot. It’s one of the only places on Earth that can actually use that oil. Major commodities traders are reportedly reaching out to Indian refiners, offering to sell them Venezuelan crude as soon as March this year. By all accounts, this could be a big opportunity for us.

The opportunity isn’t straightforward, though. Venezuela has a lot of oil, yes, but it’s some of the hardest oil to refine in the world.

Understanding Venezuelan oil

In theory, Venezuela should be the world’s greatest oil powerhouse.

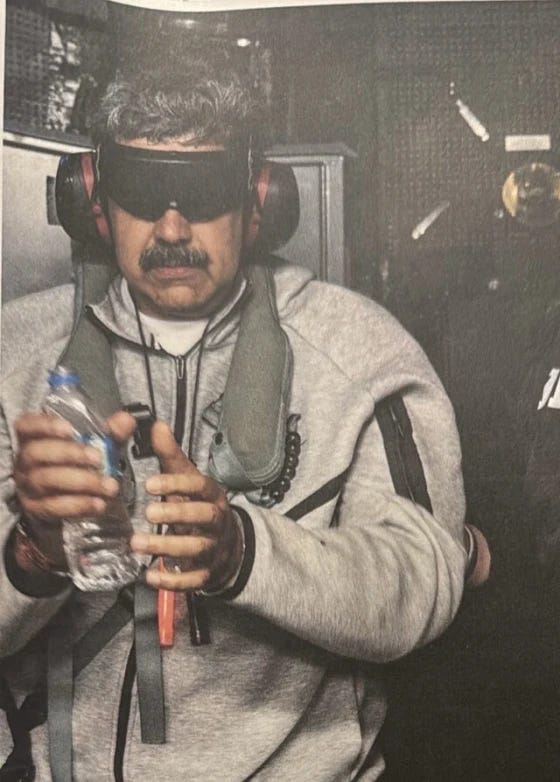

The country is home to one of South America’s largest rivers, the Orinoco. In its basin, towards the east, lies more oil than discovered in the rest of the world. The ground, there, holds more than a trillion barrels of oil, in what is called the “Orinoco Oil Belt”.

Not all of it can be pulled out commercially. But when you count recoverable oil alone, Venezuela still has the largest oil reserves of any country on earth — 303 billion barrels — or 17% of the world’s proven reserves.

Back in the 1990s, the country was one of the world’s top five oil producers, pushing out 3.5 million barrels a day. But then, the industry fell apart, due to a mix of political moves, underinvestment, and American sanctions. Today, the country barely produces a quarter as much.

But quantities, alone, only only give you half the picture. Not all oil is made the same.

The many shades and weights of oil

There are countries that produce oil that is light in colour — almost yellow-ish, in fact — which flows easily.

There are other countries that make a thick, tar-like sludge that barely moves.

These are both “crude oil” in theory. But they behave very differently.

“Crude oil‘ isn’t just one thing. It’s a mix of different hydrocarbons. When it is first created — from buried marine creatures transformed by millions of years of heat and pressure — most of that oil is made of small chains of carbon. These tiny molecules flow easily, as light oils. They’re also the most valuable: they yield the most petrol or jet fuel.

Over time, though, microbes start attacking the oil, consuming its lighter molecules. They leave behind just the dense, complex molecules. These make the oil heavier, and have it burn less cleanly. It’s only the oil preserved well out of those microbes’ reach, deep underground, that remains light.

Then, there are impurities.

Back in the 19th century, oil prospectors tasted new samples of crude oil to check its quality. The best oil would smell nice, and taste almost sweet. Meanwhile, worse grades tasted sour, or even bitter, and smelt of rotten eggs. This gave their names — sweet oil, and sour oil.

The difference, it turned out, lay in oil’s sulphur content. The best oil was created in fresh water, or in places where there was little sulphur in the seas. This gave rise to the sweet crudes of today — with under 0.5% sulphur, by weight. Much more commonly, however, oil would form in oxygen-starved, sulphur-rich seas. Over the eons, that sulphur would mix into the hydrocarbons, creating sour crudes.

That sulphur causes all sorts of problems now. It eats into our pipes, and renders catalysts useless. More importantly, it releases sulphur oxides when burnt — which are dangerous pollutants the world is trying to turn away from.

Commercially, the most valuable oils are as light and sweet as possible. Venezuelan oil, in contrast, is some of the sourest, densest oil there is.

How to market Venezuelan oil

Orinoco crude is a tar-like thing. It doesn’t flow like a liquid. You can’t pump it out of the ground at regular temperatures. To pull it out, you need to inject steam into the ground, or pump in expensive, light hydrocarbons like naphtha.

In fact, Venezuela’s oil industry crashed, in part, because the United States refused to send it any naphtha, back in 2019.

Even when the oil is brought out, it’s hard to work with.

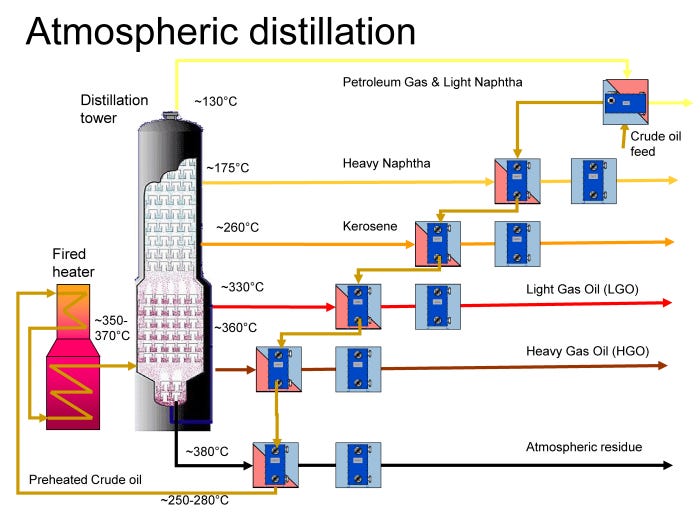

It’s fairly easy to refine light oil. After some minor processing, you essentially just heat it in a giant tower. Different components — gasoline, kerosene, naphtha, and the like — boil at different temperatures, and you can collect them all separately.

Try that with Venezuelan oil, however, and most of it will remain stuck in the tower as residue.

This grade of crude requires far more complex systems to refine. You have to process it heavily to remove sulphur and heavy metals. Then, you run it through all sorts of processes to make it useful. For instance, there are machines called “hydrocrackers”, which use hydrogen to “crack” heavy carbon molecules into several lighter ones — creating valuable fuels like diesel or jet fuel. Similarly, you use vacuum distillers, which heat the oil in vacuum, so that it boils much more easily. And so on.

Meanwhile, your refinery must survive corrosion from all sorts of acids and salts that Venezuelan oil tends to create.

The capabilities of any refinery are measured under the “Nelson Complexity Index”, or NCI. The more “complex” a refinery is, the more sophisticated are the operations it can undertake. Simple refineries usually score 2-3 on the index. To process Venezuelan oil, you need a refinery that scores at least 10. This is extremely expensive to set up — with costs anywhere between $10-25 billion.

Sizing India’s opportunity

This is where India enters the story.

India is one of the world’s most modern, efficient oil refining hubs in the world — and one of the only places that can refine Venezuelan crude. Reliance’s Jamnagar refinery has an NCI of 21.1, which is perhaps the highest in the world.

Other Indian refineries, too, are on the complex end of the spectrum. After all, without any fuel sources of our own, we went for optionality — building with the aim to use fuels of any sort. Nayara, for instance, has an NCI of ~12. Many public sector refineries, too, approach similar levels of sophistication.

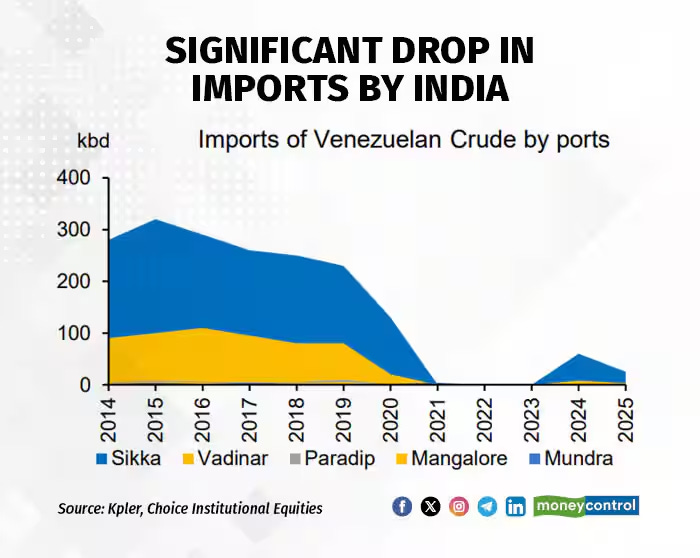

In the past, we imported large amounts of crude from Venezuela. Back in 2013, for instance, 12% of our crude imports came from there. Since then, however, we were forced to wind our imports down to almost nothing — as the United States stepped up its sanctions pressure.

But could we become major importers of Venezuelan oil once again?

Where will all that oil go?

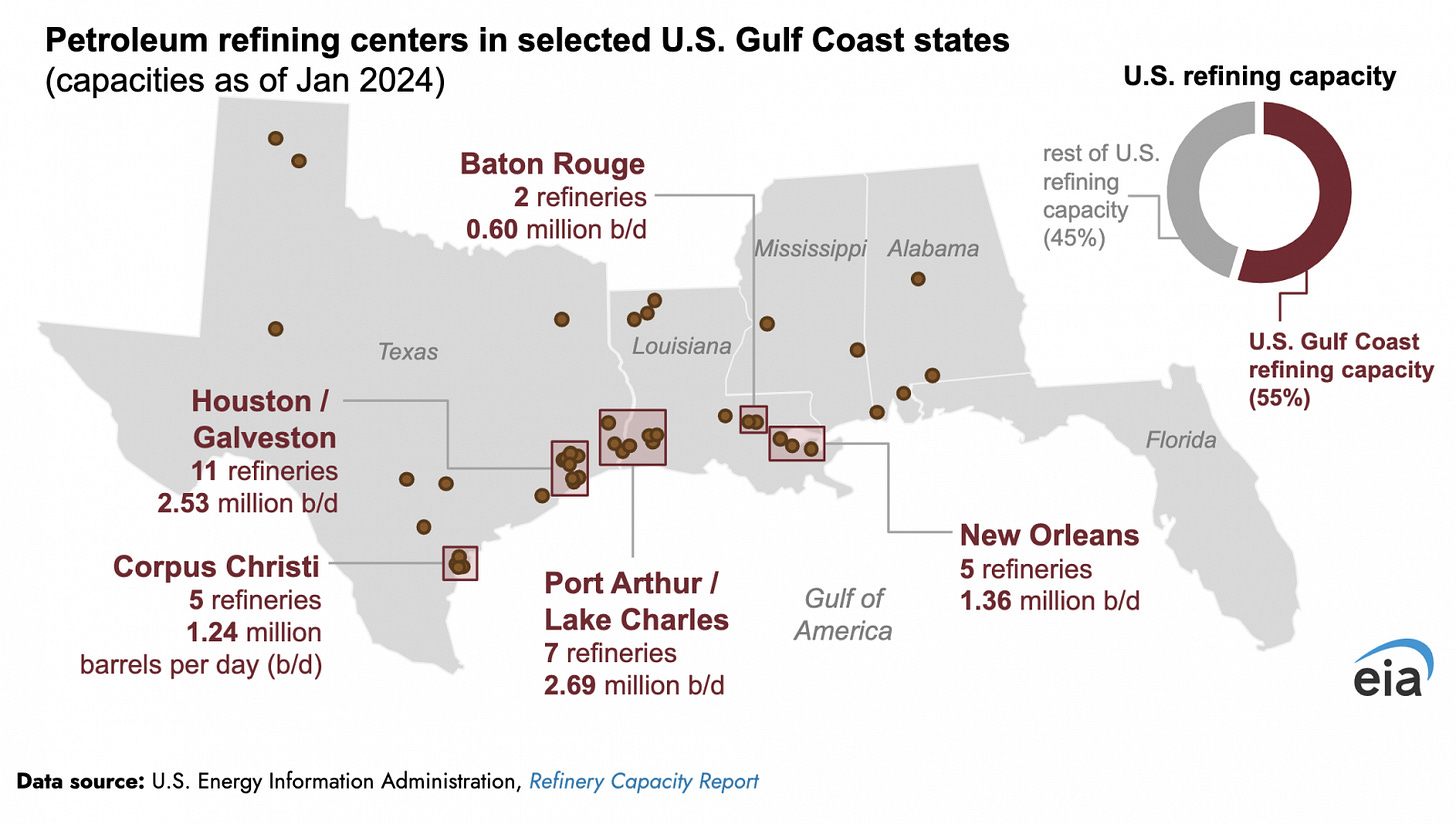

The United States, one should expect, shall be the first port of call for any new Venezuelan oil exports. After all, its refineries are built for this purpose.

The United States’ oil industry has a little known paradox. Most of the oil the country produces is light and sweet. But most of its refineries are all meant for heavy, sour oil. Which is why, funnily enough, it exports its own crude abroad for refining, while importing heavy oil to its own refineries.

That refining capacity, by and large, sits in the Gulf of Mexico. It was set up there in the 1990s — before the United States’ own shale revolution — specifically to refine oil imported from Mexico and Venezuela.

These facilities are relatively close to Venezuela — around 2,000 miles away. That is a voyage of 4-5 days, which would cost roughly half a dollar per barrel. If Venezuelan oil production goes up, this is the first place it shall reach.

But the United States’ capacity is not infinite. At its peak, the United States could handle 1.6 million barrels of Venezuelan oil a day. It could perhaps handle those quantities once again. But if Venezuela’s oil exports start exceeding that level, it will have to look for other buyers.

Those are in short supply. A lot of capacity that was initially built around Venezuelan crude has now fallen into disrepair. Very few markets, today, can make use of its oil.

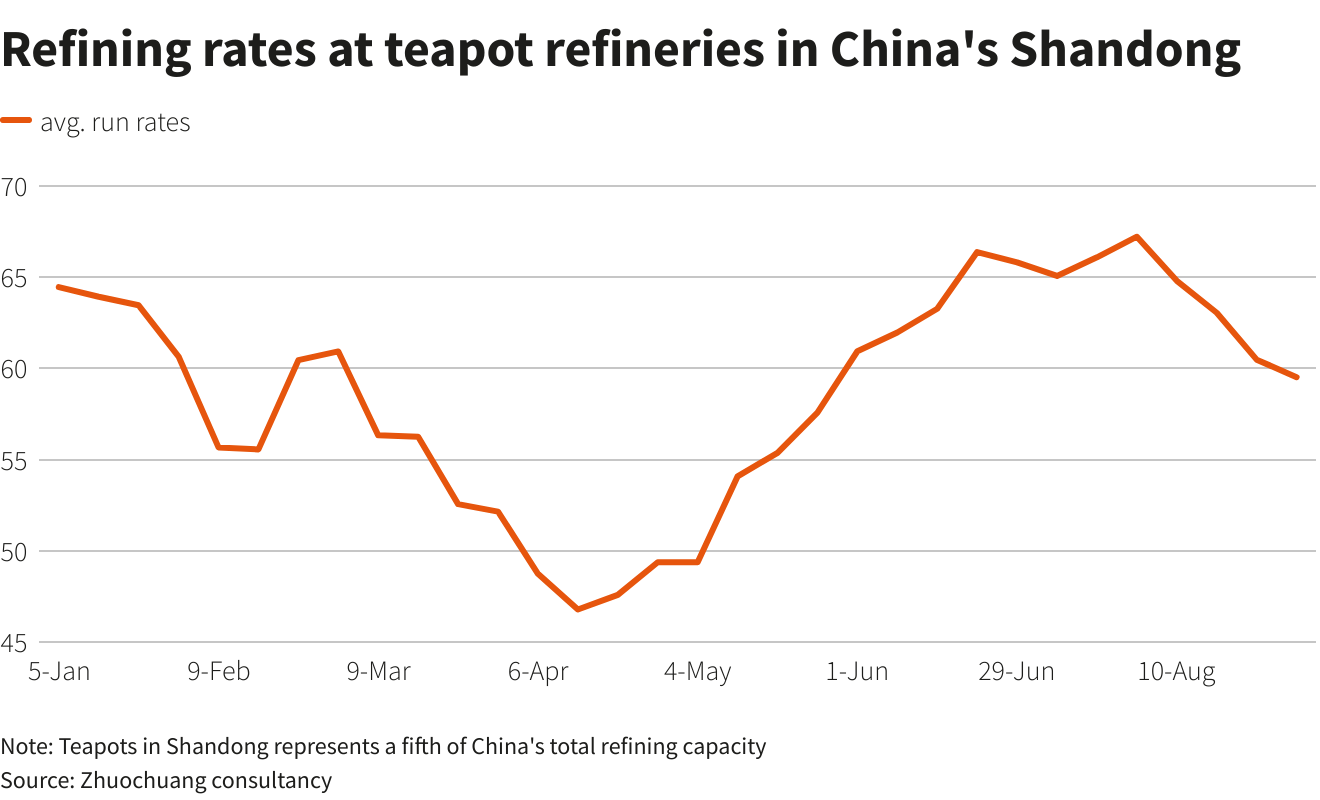

In recent years, in fact, China’s unofficial “teapot” refineries have been the only ones willing to flout American sanctions and buy Venezuelan oil. But China isn’t the market it once was. Its oil appetite has gone down in recent years — as consumption has flatlined, while many of the country’s vehicles have turned electric.

This brings India into the fray.

India’s imports, and the strings attached

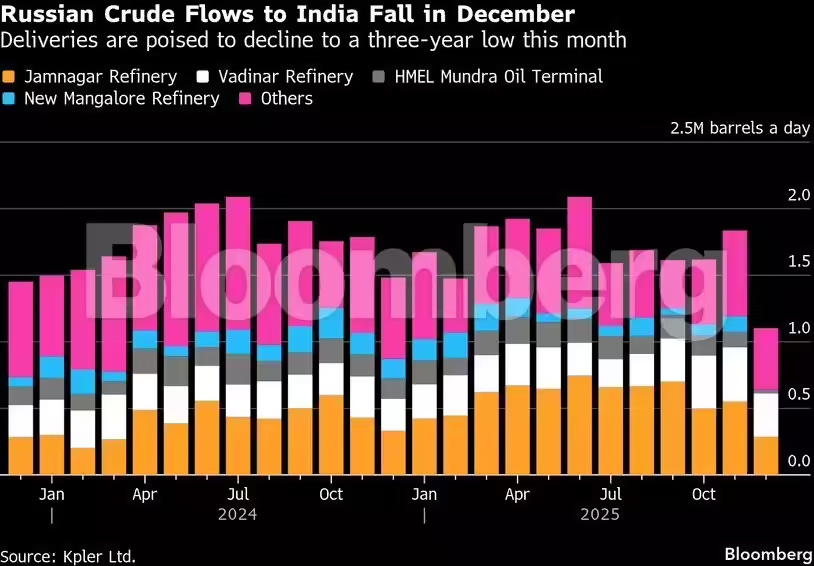

When Russia invaded Ukraine, back in 2022, India swept in to reap the rewards. The West had turned its back on Russian oil — giving us an instant discount of $8-10 per barrel. From 2% of our import basket, Russian oil quickly grew to more than one-third of our oil imports, by FY 2025. In all, this saved us billions of dollars.

But then, last year, the West stepped up its pressure. Indian refiners were forced to play along. By December 2025, our imports from Russia were dropping significantly.

Venezuelan oil, now, offers the chance of a swap.

The case for those imports isn’t automatic. After all, Venezuela sits across the world — 9,800 nautical miles away. To reach India, from there, its crude will have to make a 40-day long voyage. That could also translate into a cost of as much as $4 per barrel.

At the right discount, though, the trade could still make sense. We’re arguably the best refining destination for Venezuelan crude outside the Southern United States. If things line up, and we receive it for cheap enough, this could be a second windfall in five years for Indian refineries.

This time around, things shall look very different from our dealings with Russia. After all, we wouldn’t be dealing with an international pariah, but with the strongest country in the world. The biggest variable will be the United States, and what it decides to do. The US will gate access to Venezuelan oil, and any payments will flow through US-controlled accounts.

That has an upside and a downside. On one hand, we probably won’t have to improvise the plumbing needed to deal with sanctions of all sorts. On the other, it all depends on the pleasure of the United States. It will set conditions on which any trade shall happen — and at least off late, it has been eager to throw its weight around. The country’s oil could become yet another geopolitical bargaining chip.

For all that, however, this is a distinct opportunity.

Everything is still in the air

Before we close this story, we want to mention just how contingent this all is.

Venezuelan oil, right now, is in a bad state. It isn’t entirely clear how many of those 303 billion barrels are actually within our reach. Years of neglect have left pipelines rusted, upgraders broken, and fields half-abandoned. Even ExxonMobil — which knows the country well, and once operated there — has described Venezuela as “uninvestable” as things stand.

To actually make anything of Venezuela’s oil industry, Trump will have to offer it something that isn’t his strongest suite — stability. If not, this window could shut as quickly as it opened.

Are Local Indian Governments Spending Enough?

Anyone who has lived in an Indian city knows the frustration of waterlogged streets after mild rains and endless potholes. Our cities are growing fast, yet the money going in to fix basic infrastructure is nowhere in sight.

To put numbers behind this, India’s municipal bodies put together spend just around 1.3% of the country’s GDP. For comparison, China’s local governments handle roughly a quarter of China’s GDP in spending, acting as powerful engines for local development. U.S. city and state governments, too, account for nearly 20% of the U.S. GDP.

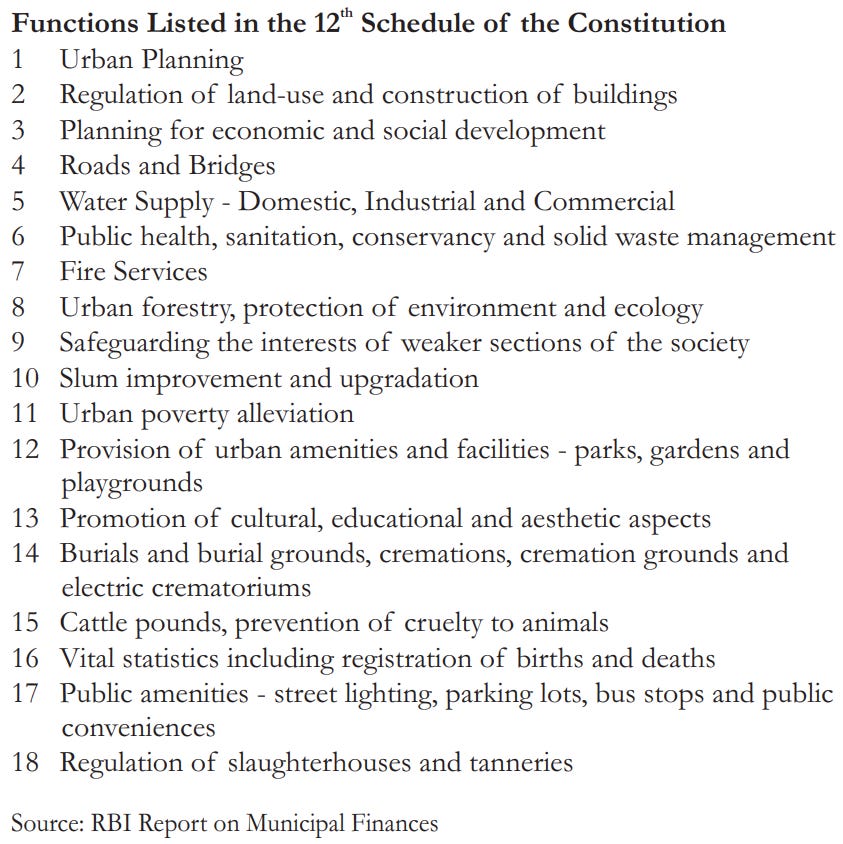

Indian city governments are financial lightweights by global standards, despite an ever-expanding list of constitutional responsibilities. Cities need to spend a lot more to keep up with the needs of their citizens. Money isn’t the only problem, of course, but it’s a big one – and right now, local governments just don’t have enough of it.

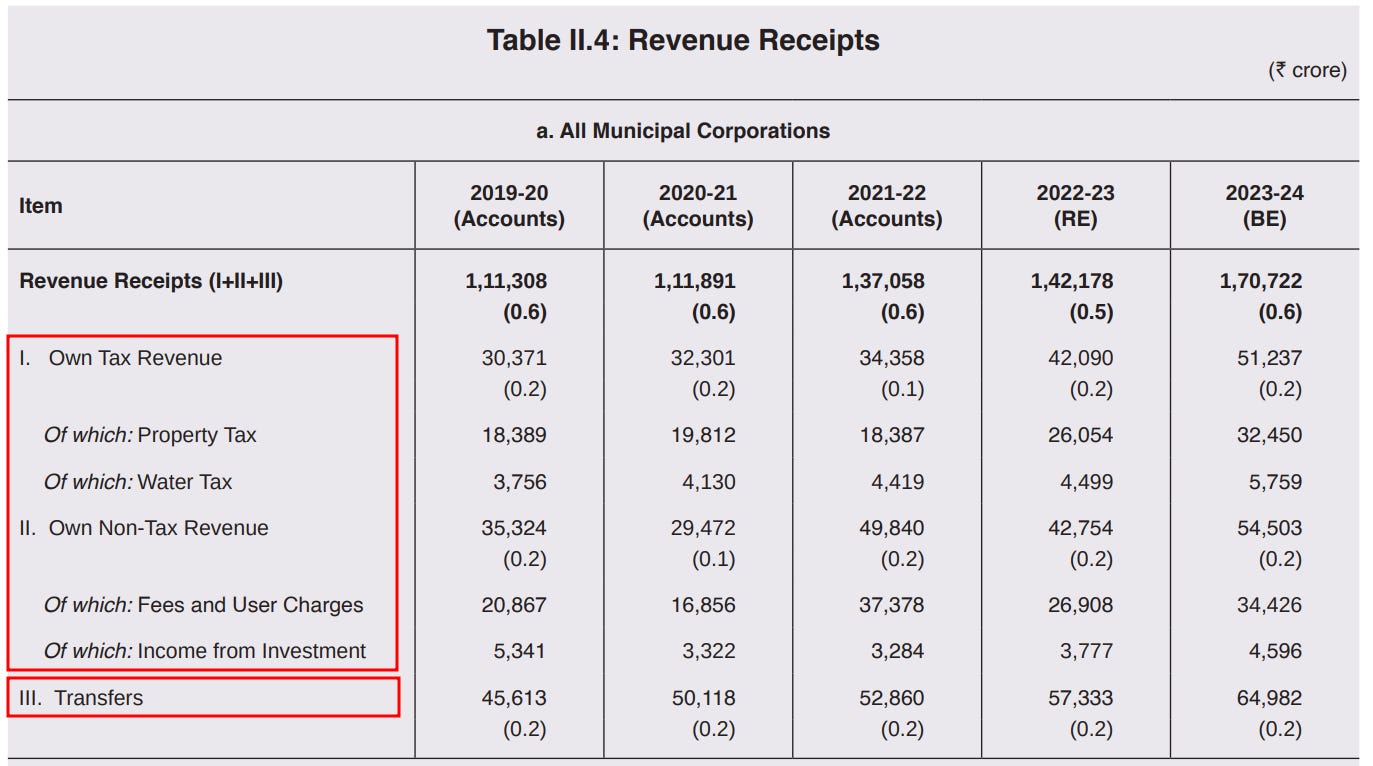

Traditionally, cities rely on two funding streams: their own revenue (from taxes and non-tax sources, water charges, parking fees, etc.) and transfers (or grants) from state or central governments. We’ve explored previously how these sources have proven inadequate. As a result, municipalities often find themselves cash-strapped, struggling to cover even day-to-day expenses.

If cities can’t boost these income streams easily, the other obvious way to raise funds is to borrow – and that’s where municipal bonds come into play.

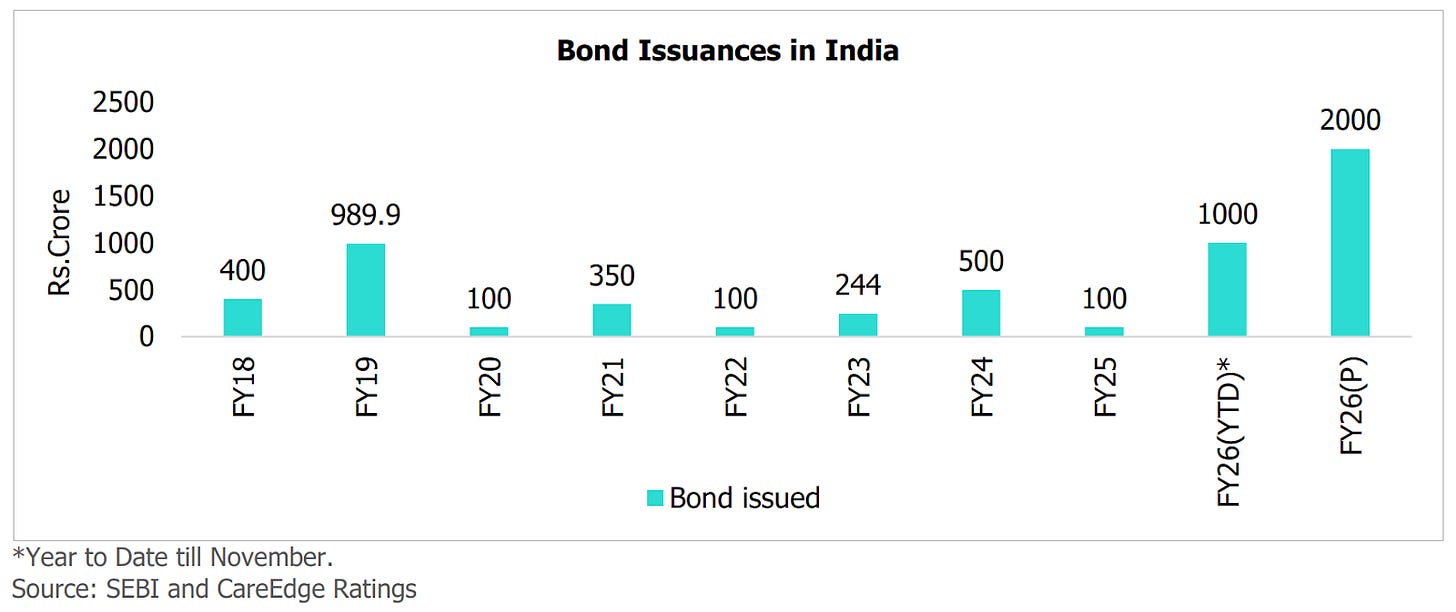

Municipal bonds are debt instruments issued by city governments (urban local bodies) to finance projects. We’ve spoken about them as well at length earlier. They’ve been around in India since the late 1990s, but never really took off.

To put it in perspective, as of March 2024 all outstanding Indian municipal bonds amounted to just about ₹4,200 crore, a drop in the bucket. In fact, of the total borrowings made by municipalities, bonds make up barely 18% meaning that most city borrowing still comes from bank loans or government loans.

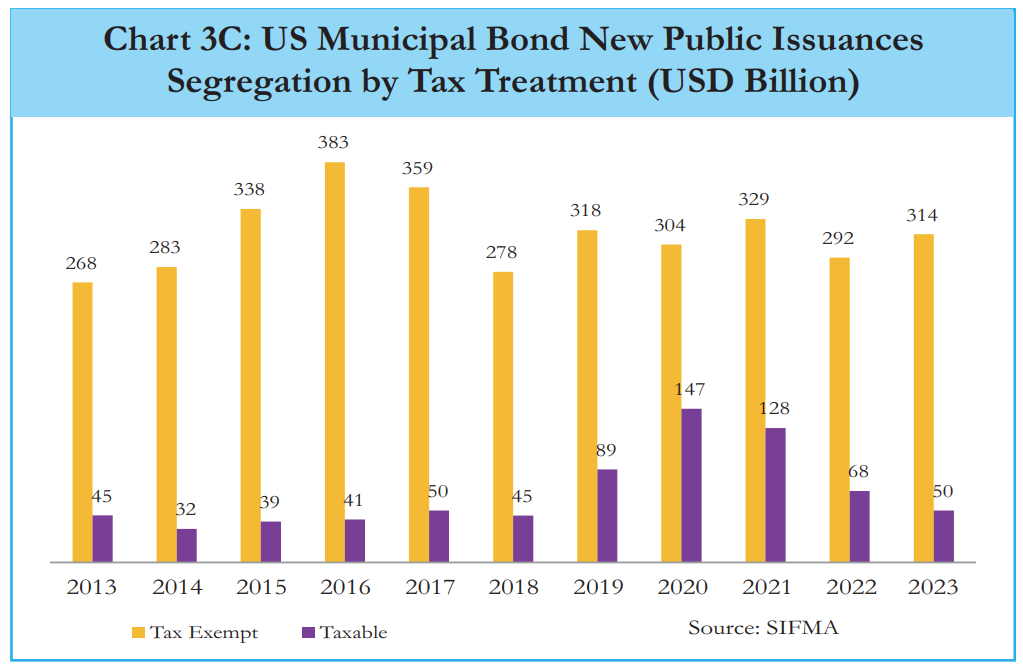

This is nothing like the US,, where thousands of cities routinely raise trillions through municipal bonds to build local infrastructure. Just to get a sense of scale: the U.S. muni bond market is roughly $4 trillion — about the size of India’s entire GDP. (Yes, comparing someone’s local-government debt to another country’s GDP is a bit silly. But it’s a useful “wow” number.)

So the big question is: why hasn’t India’s municipal bond market taken off, despite the obvious need and potential? That’s what we’ll be diving into now.

Why Are Municipal Bond Issuances So Low?

At first glance, you might suspect the problem is that our city governments have lousy finances. They are either too broke or risky to borrow. But, that’s not entirely true.

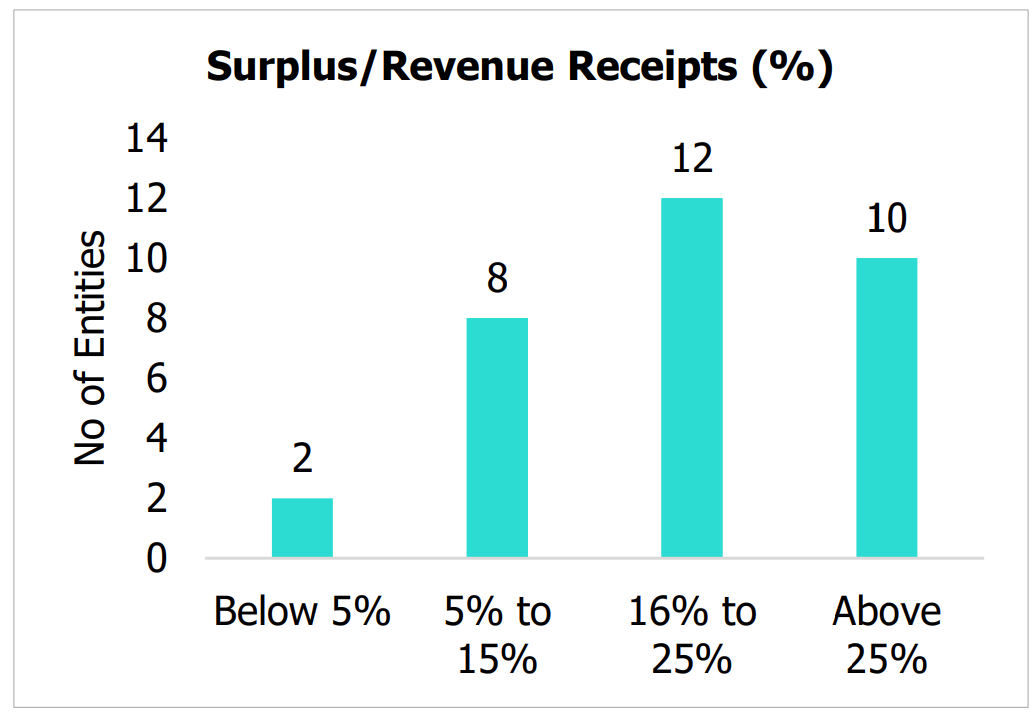

Many Indian cities, especially larger municipal corporations, are actually running consistent revenue surpluses year after year. They earn more than they spend on operations. In a CareEdge analysis of 32 major urban local bodies, revenues grew about 13% annually from FY21 to FY25, and every single one of those cities reported a surplus in their budget.

With numbers like that, these cities do have some headroom to take on debt. In fact, analysts estimate that financially healthy municipalities could collectively raise an additional ₹25,000–30,000 crore via bonds over the next 5–8 years without compromising their stability.

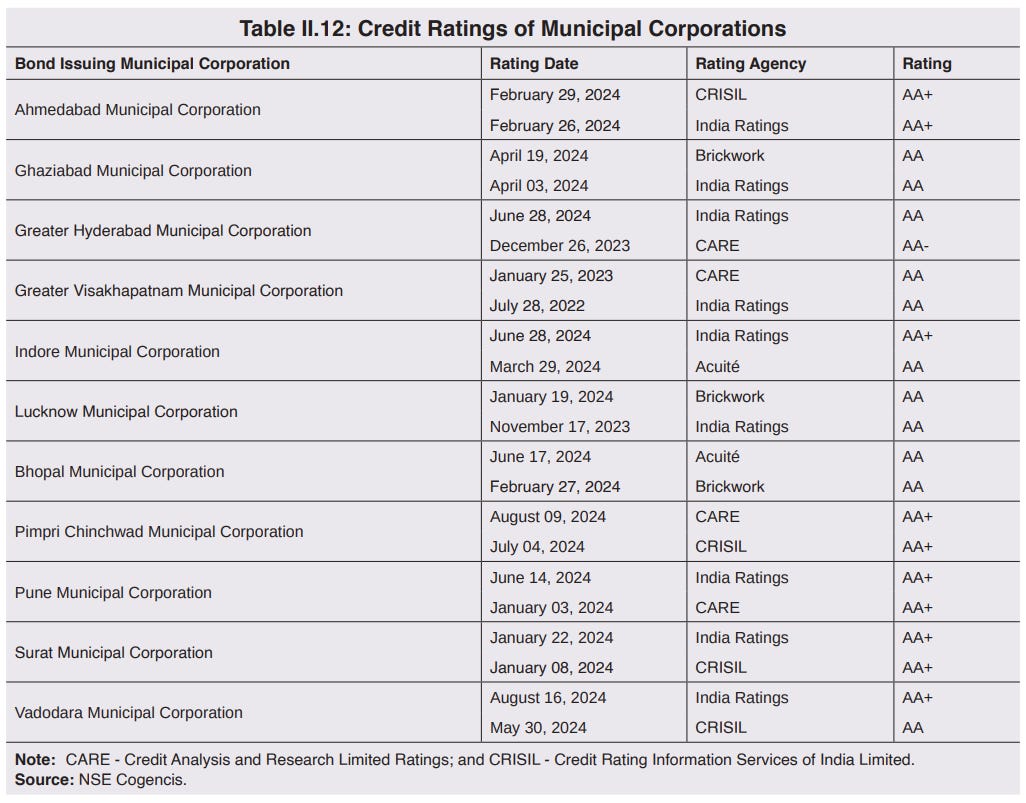

Also, these bonds aren’t junk-grade by any means. The issuers so far have mostly been big cities like Pune, Ahmedabad, or Indore. And virtually all municipal bonds issued carry credit ratings in the investment-grade A category, or higher.

So if it’s not abysmal finances or credit risk keeping investors away, then what’s the problem? It’s several deeper issues.

For starters, city governments simply don’t have the freedom to borrow. By law, most municipalities can’t issue bonds or take on debt beyond certain limits without explicit permission from their state government. In fact, as of 2022, only two states (Odisha and Bihar) explicitly allowed their cities to float bonds by default. Everywhere else, a city has to go hat-in-hand to the state for approval on each bond issue. This federal structure means cities lack true fiscal autonomy.

But even if they could borrow, another issue awaits them. While many urban legislative bodies (ULBs) have surpluses now, their future revenue streams are limited, which in turn limits how much debt they could service. Key tax bases like property tax are notoriously under-exploited — raising rates or improving collection is politically difficult, so revenue grows only modestly. Non-tax revenues (fees, user charges) are also not fully tapped.

Unless cities boost these revenues, there’s a natural ceiling on sustainable debt. Having no fiscal autonomy makes this even harder and aggravates the problem. To an investor too, a bond from a municipal body in India often isn’t especially attractive relative to other options. Why buy a city bond yielding, say, 8% when you could buy a safer central government bond at 7%, or a higher-yield corporate bond?

In countries like the US, there’s a crucial sweetener: interest from municipal bonds is tax-exempt, which makes their effective returns very appealing to investors. India, however, does not offer any broad tax exemption on municipal bond interest. There have been a few limited tax-free municipal bonds in the past for select projects, but there’s no blanket policy.

So, municipal bonds have to compete on pure yield and while they do offer a bit higher interest than government bonds, it’s often not enough to compensate for the perceived extra risk and the tax hit.

If low returns weren’t enough, the municipal bonds that do get issued in India tend to be tiny in size and often privately placed. Each issue is like a bespoke deal, with its own tenure and structure, that a few institutional buyers may hold to maturity. But this lack of standardization doesn’t make them too attractive to retail investors.

There’s a structural angle too. Culturally, many city administrations in India have been hesitant to take on debt at all. They often operate with a short-term, annual budgeting focus. Long-term capital investment planning is rare; instead, the norm is to balance this year’s budget and hope for grants for any big projects. Taking on a bond means committing to a 7-year or 10-year repayment plan — something many local politicians shy away from, fearing it could become a headache. This attitude has certainly held back borrowing.

Given all these challenges, it’s no surprise that municipal bond issuance in India has been minuscule. However, that script is slowly changing. Recent developments suggest that with the right nudges and reforms, cities are starting to overcome some of these hurdles.

A Slow Revival, Thanks to Quick Fixes

This fiscal year (FY26) is on track to be the busiest ever for city bond issuances. By December 2025, nine municipal bond issues had hit the market — a big jump from only three in the whole previous fiscal year. In terms of money, ~₹1,000 crore was raised in the calendar year 2025 alone, pushing total outstanding muni bonds to ~₹3,800 crore.

If current trends hold, total issuances in FY26 could reach around ₹2,000 crore — two-thirds of the entire amount raised in the last seven years put together. Notably, some of the recent bond floats have come from first-time issuers – cities that had never accessed the bond market before are now taking the plunge.

Clearly, something has changed in the landscape to spark this revival. That “something” is a series of policy boosts and regulatory tweaks over the past couple of years.

For one, the central government, under the AMRUT 2.0 urban mission, is literally paying cities to issue bonds. A first-time municipal bond issuer gets a grant of up to ₹13 crore for every ₹100 crore raised. That’s a sizable sweetener – it effectively subsidizes the city’s borrowing cost.

More recently, the Union Budget of 2025-26 announced a new “Urban Challenge Fund” of ₹1 lakh crore aimed at co-funding city infrastructure projects. Under this, the fund would put in 25% of the project cost as a seed grant, but on the condition that 50% of the costs should come from borrowings. This effectively nudges local bodies to get into the borrowing habit.

Another tweak came from the RBI in August 2025. It allowed banks to offer Partial Credit Enhancement (PCE) to municipal bonds. Under PCE, a bank can underwrite a portion of the bond issue or provide a guarantee for some payments, which can bump up the bond’s credit rating. That’s a big deal for institutional investors like pension funds, which mostly filter for higher-rated bonds. This widens the pool of potential buyers and should make it easier for cities to raise funds — possibly at lower yields too.

Another important quick fix was the decision to treat municipal bonds as eligible collateral in repo transactions (effective October 2025). At the end of the day, banks might have a shortfall of money, and might need to borrow money to fill that, which they do from the overnight repo market. For this borrowing, banks earlier pledged their government securities as collateral, but now municipal bonds are allowed, too, making them more tradeable.

All these measures have lowered the barriers to entry for municipal issuers and made investors more receptive. The recent flurry of bond issues from cities like Surat, Indore, Ghaziabad, Vishakhapatnam and others — some of which are first-timers in the market — indicates that with the right push, urban local bodies are willing to tap into market funding.

That being said, even a record ₹2,000 crore of issuance in a year is tiny compared to the trillions needed for urban infrastructure. The quick fixes have delivered a spark, but whether that turns into a steady flame is yet to be answered.

Conclusion

In the long run, the only real fix for India’s urban funding crunch is to empower city governments financially and administratively. The recent surge in bond issuances is encouraging, but it’s largely driven by top-down incentives and one-off tweaks.

Structurally, cities need greater fiscal autonomy. This means revisiting laws that shackle municipal borrowing and budgeting. Requiring state government approval for every debt issuance is a recipe for delays and under-investment. The fact that only two states allow this freedom by default is quite telling.

Autonomy isn’t just about the right to borrow, but also the power to tax and charge. This could involve politically tough reforms like empowering municipalities to update property values regularly for taxation, levy congestion charges, or share in newer taxes. The RBI’s municipal finance report even suggested sharing a portion of GST with city governments to give them a buoyant revenue source.

Such solutions will require more rigorous debate and political will that may take a long time, even years. But the needle has indeed been moved to start with.

Tidbits

Bajaj Finserv has completed India’s largest insurance sector deal, acquiring Allianz’s 23% stake in Bajaj General Insurance and Bajaj Life Insurance for ₹21,390 crore. The transaction ends a successful joint venture that began in 2001 and gives the Bajaj Group 97% ownership. Allianz, meanwhile, isn’t exiting India — it’s pivoting to a new 50:50 reinsurance venture with Jio Financial Services.

Source: Business Standard

India’s rice shipments to Iran have nearly stopped amid civil unrest in the Gulf nation and Trump’s threat of a 25% tariff on countries trading with Tehran. Iran is India’s second-largest basmati market, accounting for $468 million in exports during April-November. Exporters are now wary of signing new contracts due to payment risks — some Iranian buyers have reportedly fled the country.

Source: Reuters

Palm oil imports hit 8-month low as refiners pivot to rivals India’s December palm oil imports fell 20% month-on-month to 507,000 tonnes — the lowest since April 2025 — as refiners shifted to soyoil and sunflower oil amid weaker winter demand. Soyoil imports jumped 36%, while sunflower oil more than doubled to a 17-month high.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Kashish.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

By processing Venezuelan Crude, your output for the Coker units gets significantly poorer, thus you get only asphalt grade coke and not your needle coke, needed for CNC in anodes.

So, Indian refiners' gain is steelmakers' pain!! Shows how interconnected modern businesses are!!

When you say borrowing by municipality only thing comes to mind is corruption all around.

What will they do by borrowing? By having more money?

They will only be more corrupt.

Just look at the level of corruption in Indore the so very wrongly called cleanest city of the country for seven years in a row. The nagar Nigam even lost the property tax records for the whole of region last year and was demanding the proof from the tax payers else one needs to repay the already paid tax. So much for digital india and growth.