Why Samsung and LG Are Upset With India

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Why Samsung and LG are headed to court

The world is aging. But healthily

Why Samsung and LG are headed to court

Samsung and LG just took the Indian government to court.

Why? A new rule that forces electronics companies to pay a fixed ₹22 per kilogram to recyclers for electronic waste. The rule is meant to clean up how India handles its mountains of used electronics. But it has sparked a legal battle instead, with both companies arguing it’s unfair, expensive, and won’t actually fix the root problems in India’s e-waste system.

The stakes are huge.

India is the third largest generator of electronic waste in the world, after China and the United States. We produce over 3 million tonnes of e-waste every year — everything from old smartphones and broken laptops to discarded refrigerators and TVs. Less than half of this — just 43% — is formally recycled. Everything else goes to little cottage industries in the unorganised sector — places like Seelampur, near Delhi.

Seelampur is where your old phone goes to die. In a chilling report from FactorDaily, journalist Pankaj Mishra described it as India’s “digital underbelly.” He walked through lanes filled with the guts of discarded electronics — men, teenagers, even children sitting by piles of motherboards, circuit boards, and phone parts, pulling them apart by hand. Acid washes are used to extract silver and gold. Torches melt down parts to get copper. It’s dangerous, often deadly work. The air is thick with toxic fumes.

Workers earn around ₹200 a day, sometimes less. They suffer from respiratory problems, exposure to lead, mercury, and cadmium—all just to get tiny amounts of precious metals out of trash.

But people are simply learning to live with it. As one worker put it: “E-waste is just the new waste. We’ve been doing this for generations.”

It’s this informal world that the Indian government is now trying to reform.

So what exactly is the policy?

The government brought in its e-waste rules in 2022, which took full effect in 2023.

At the heart of these rules is something called Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). The idea is simple: if you make or sell electronics, you’re responsible for what happens to them after they die. That means the producers have the responsibility of collecting and safely recycling at least some amount of the e-waste your products generate.

Now, here’s the issue, and the reason companies like Samsung and LG are furious. In late 2024, the government fixed a minimum price that these companies must pay to recyclers. For most consumer electronics, that’s ₹22/kg. This isn’t a suggested rate. This is the law. Even if a recycler is willing to do it cheaper, the company is not allowed to pay less.

And if they fail to meet their recycling targets, they can be fined at rates like ₹74/kg or more.

Of course, this ₹22/kg rate must be paid only to registered, formal recyclers. The law doesn’t even formally recognise the existence of informal players — who still handle the bulk of collection. This creates a disconnect between where the waste actually goes and where the money flows.

Before this rule, companies had far more flexibility. They could negotiate lower rates with recyclers. In fact, many paid just ₹5 or ₹6/kg to dismantlers. Often, they didn’t handle recycling themselves — they outsourced it, sometimes indirectly, to the very same informal sector that burns wires or melts parts in acid.

The government’s logic is that this had created a race to the bottom: recyclers were being paid so little that they had no option but to cut corners and pollute. So by introducing a floor price, the government hopes to make proper recycling a viable business — and push out the dangerous, informal practices.

But it’s not that simple.

Companies aren’t convinced. Samsung claims this will increase their recycling costs by 5-15 times. LG argues that this is just an excuse to fleece companies under the guise of the “polluter pays” principle. Their fundamental argument is that India’s failure to create a thriving formal recycling industry is a problem our governments created, and the responsibility of fixing it has been thrust on them.

But how does the recycling supply chain actually work?

So, how should you see this problem? As a first step, you should know how the recycling industry works.

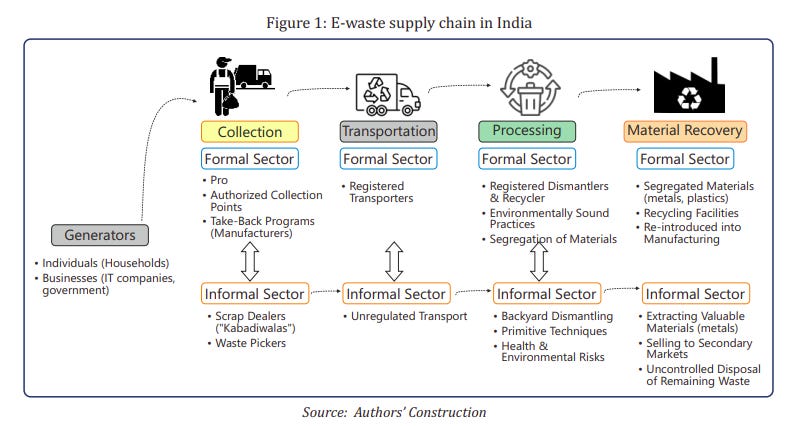

India’s e-waste recycling supply chain has multiple layers:

It all begins when consumers throw away their devices.

These are picked up — in theory by formal collection agents, but most probably by kabadiwalas (scrap dealers), who act as informal aggregators.

The scrap is then passed on: ideally to formal dismantlers, but more often to informal dismantlers, who pull apart the devices and extract anything of value.

What remains is then sold to recyclers, who may or may not be formally registered.

Of course, a formal recycling ecosystem exists too — companies that follow environmental rules and have the necessary tech. But they are few in number. Many don’t have the advanced infrastructure needed to safely recover rare earth materials or handle hazardous waste.

And crucially, even formal recyclers often depend on the informal sector to supply them the actual waste. According to a 2024 report by ICRIER, over 90% of India’s e-waste collection and dismantling is still done informally. The informal sector — made of kabadiwalas, waste pickers, backyard dismantlers — plays a critical role in making e-waste flow.

They gather waste efficiently, even if the methods are unsafe. Formal recyclers usually step in only at the final stage, if at all — once the waste has already been stripped and sorted.

This creates a strange duality. The formal sector, to the extent it works, is dependent on the informal sector. But the new policy doesn’t address how these two should work together. In fact, by focusing only on registered recyclers, the ₹22/kg rule leaves out the rest of the supply chain completely. This is a major blind spot.

Is this a structural problem?

There’s a deeper issue here: India doesn’t yet have the infrastructure to support fully formal e-waste recycling.

Building collection centres, advanced dismantling facilities, and smelting units for rare metals isn’t cheap. It will require huge capital expenditure (capex), and the government hasn’t made any real financial commitment yet. A report by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs even suggests that eco-parks and centralised recycling hubs are still just pilot ideas in most cities.

What’s worse, the EPR rules themselves are vague. Companies are told to meet recycling targets and use CPCB-registered recyclers. But the rules don’t explain how they should actually collect waste, how they should deal with informal actors, or whether they can count informal collection towards their targets.

In theory, this problem was to be solved by a layer of intermediaries — PROs (Producer Responsibility Organisations) — who were supposed to act as middlemen, linking companies with collectors and recyclers. But in practice, their role is poorly defined, and the EPR credit system they operate under isn’t transparent. Companies end up either overpaying to meet their targets or risk getting fined. It’s easier for them to simply act as rent-seekers.

Meanwhile, systemic issues still persist. These intermediaries haven’t catalysed the creation of an end-to-end formal recycling set-up. Nor can these formal recyclers compete with the informal sector on price.

How do things work in more mature markets?

Let’s take the United States first. The U.S. doesn’t have a single national e-waste law. It’s left to the states. Some—like California, New York, and Oregon—have solid Extended Producer Responsibility laws. Others have none. In most states, manufacturers do have to pay for recycling. But crucially, they aren’t forced to pay a fixed price like ₹22/kg. They independently negotiate contracts with recyclers or pay into programs based on sales volume. In California, consumers actually pay a small recycling fee when they buy electronics. But there’s no price floor. The market decides.

In China, things are more centralized. The government collects recycling fees from companies—like a tax—and puts that money into a national e-waste fund. Recyclers who are officially approved can claim subsidies from this fund. So if a company like Haier or Lenovo recycles TVs or ACs, they get a fixed amount per item from the government. The government pays the recycler. The companies don’t directly negotiate prices.

And again, unlike India, there’s no direct ₹/kg rate the company must pay to a recycler—it’s more about paying into the system and letting the government manage the flows.

Both systems have their flaws. The U.S. suffers from inconsistency—recycling rules change depending on where you live. China struggles with subsidy fraud and over-reliance on state control. But their problems are nowhere near as large as ours.

So what now?

India’s policy is bold. It tries to formalize an entire recycling system almost overnight—using a hard floor price to make it work. But it’s clashing with how business works on the ground. Companies are pushing back hard, saying this isn’t the way to fix the problem. Meanwhile, places like Seelampur continue to exist in the shadows.

The transition from informal to formal won’t be easy. It will take more than price floors. It will take infrastructure, incentives, enforcement—and empathy.

Maybe the question we really need to ask isn’t “how much should Samsung pay?” but “how do we build a recycling system where no nine-year-old girl is coughing up acid fumes to extract gold from phones we no longer want?”

The world is aging. But healthily.

We recently wrote about the IMF World Economic Outlook report a few days back. But we only covered the first chapter out of the three published. And that just scratches the surface of how the IMF sees the global economy.

The next chapter discusses a deeply interesting new trend — what economists are calling "the silver economy". As Western economies grow older, they look at how economies develop and accommodate their older citizens. This is a problem that most economies in the world will have to confront eventually. Which is why we’re deeply curious about the first cohort of countries that are doing so.

Let’s dive in.

The big picture: global aging is accelerating

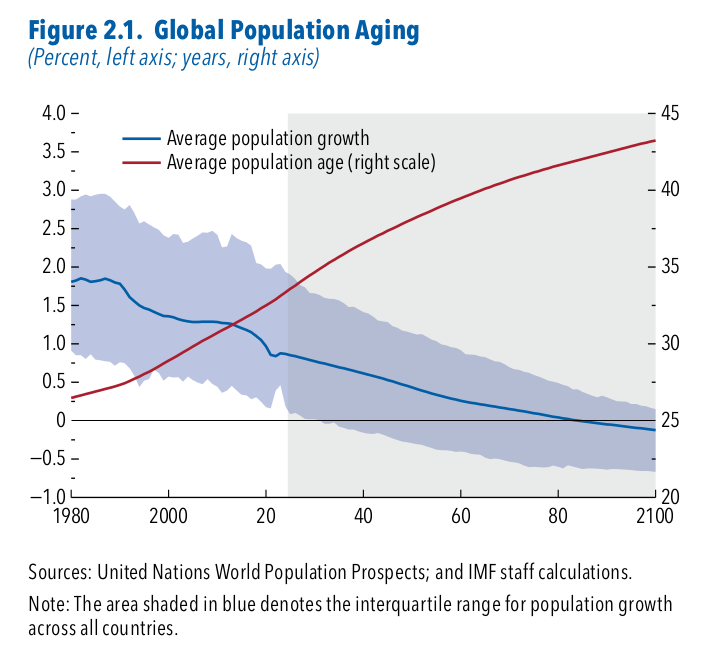

The IMF's report confirms what many demographers have been warning about. Populations across the globe are aging rapidly, largely due to two primary forces: declining birth rates and increased longevity. In fact, the IMF predicts that the average age of the world’s population will increase by 11 years between 2020 and the end of the century.

Birth rates are falling worldwide, as women get more education and job options, even as having kids gets more expensive. Moreover, better birth control, pricier housing, and changing social attitudes mean that many people choose smaller families or delay having kids.

This is happening all over the world. By 2035, all of the world’s advanced economies and major emerging markets will have crossed their "demographic turning point" — the year when the share of the working-age population begins to decline. By 2070, most low-income countries will experience similar shifts.

On average, global population growth is predicted to slow from 1.1% per year before the COVID-19 pandemic to basically zero in 2080–2100.

What would that world look like? Can you even imagine it, especially as an Indian living amongst a perpetually booming population? What would life look like as everyone you know grows older, and you see fewer young people every day?

This used to be a problem that was exclusive to the world’s wealthy nations. But that’s no longer the case. Even regions with traditionally young populations like Africa and the Middle East will see sharp increases in the proportion of older citizens.

As the IMF notes, "Aging is no longer a concern limited to advanced economies; it is a universal trend whose implications all countries will navigate throughout this century."

The economic implications of aging populations

Why is it a problem if the world grows older? See, population aging has often been tied to falling economic growth and increasing pressure on public finances.

Under current projections, global annual growth is expected to decline by about 1.1 percentage points over 2025-2050, compared to 2016-2018 averages. By the end of the century, that decline could reach 2 percentage points.

The report goes beyond growth implications, to examine how aging will affect other economic variables:

Interest rates: As populations age, that could put downward pressure on global interest rates, as savings increase relative to investment demand.

Public finances: Many countries will need higher primary balances than in recent years to keep debt ratios stable from 2030 onward.

Pensions: Aging populations put serious pressure on pension systems as fewer workers pay to support more retirees. Policymakers often delay pension reforms since aging happens gradually and the report emphasizes that waiting makes things worse.

Global capital flows: As different countries make their own demographic transitions, that could reshape global capital flows. Large emerging economies like China and India could gradually accumulate foreign assets while many advanced economies draw down their foreign assets.

But the IMF report offers another perspective, which goes beyond these stark numbers. Yes, global growth may slow. But there are a few reasons why the economic impact of population aging might not be as dismal as we think.

How? Healthy aging.

The report emphasizes that we’re seeing a rise in "healthy aging" . People aren't just living longer — their healthspans are longer. They’re maintaining better physical and cognitive capabilities into their later years.

Based on surveys conducted between 2000-2022 across 41 advanced and emerging economies, researchers examined various health indicators in people over 50, including physical capacity metrics, cognitive abilities, and self-reported health measures.

The findings paint an encouraging picture: today's seniors are generally physically stronger and cognitively sharper than previous generations at the same age. In fact, the report notes that "the 70s are the new 50s". On average, a 70-year-old in 2022 had roughly the same cognitive abilities as a 53-year-old back in 2000.

This phenomenon represents a significant economic opportunity. When older people age healthily, the report shows they:

Stay in the workforce longer (20 percentage points higher labor force participation)

Work more hours weekly (about six additional hours per week)

Earn more (30% higher labor earnings)

Retire later and experience lower unemployment rates

The IMF estimates that these healthy-aging trends alone will contribute about 0.4 percentage points to global GDP growth annually over 2025-2050.

And then, there’s AI. The report suggests that AI might actually benefit older workers more than we'd expect. Several features of jobs with high AI exposure are aligned with older workers’ preferences and capabilities. Of course, if past experience is anything to go by, older people struggle to adapt to new technologies, meaning they are particularly vulnerable to disruptions. Targeted policies are necessary to help them transition to a world where their skills are complemented by AI, not replaced.

The report also recognizes that aging affects how productive remaining workers are.

On one hand, healthy aging helps offset some negative effects by keeping older workers more productive and engaged in the workforce longer - the "silver lining". On the other hand, aging societies may see slower productivity growth beyond individual worker capabilities. Countries with fewer young entrepreneurs are less innovative.

How countries compare on cognitive capacity

There’s a particularly interesting graph in the report on cognitive capacity. It points to the systemic factors that influence cognitive health, beyond individual characteristics.

When a country appears higher on the graph (more positive value), it means that country has systemic factors that positively affect cognitive health for older adults. When a country appears lower (more negative value), it has systemic factors that negatively affect cognitive health.

While there's a clear positive relationship between a country's wealth and its elderly population's cognitive health, there are definitely variations. What’s striking is India’s position — all the way at the bottom of the countries surveyed.

This isn't just because we’re a lower-income country — the relationship is more complex than that. Although the IMF report doesn’t talk about India specifically, there are several key factors likely contribute to India's position:

Historical educational gaps: Today's Indian seniors (people now 50+) grew up when education wasn't widely available. In the 1950s-60s, less than 30% of Indians could read and write. This early educational disadvantage has lifelong effects on brain development. The IMF analysis controlled for current education levels, but it can't fully capture the impact of missed early education opportunities.

Lifelong poverty and nutrition challenges: Many older Indians experienced poverty and nutritional deficiencies throughout their lives. Even though the IMF accounted for current wealth and India has eradicated extreme poverty, these early-life factors can permanently affect brain development and function. Studies have linked food insecurity to lower cognitive function among India's elderly.

Healthcare access limitations: India's healthcare system, especially in rural areas where many of our elderly live, has historically had less capacity for specialized care for age-related conditions. Early diagnosis and treatment of conditions that affect brain health (like hypertension, diabetes, and depression) can prevent cognitive decline. Limited healthcare access means these conditions often go unmanaged.

Rural-urban divide: About 65% of India's population lives in rural areas with limited access to healthcare, quality education, and sometimes even basic services. Studies consistently show rural elders have worse health outcomes, including cognitive health.

Gender inequality: Women in India, especially from older generations, had much less access to education than men. This educational gender gap likely contributes to observed differences in cognitive function, with elderly women showing higher rates of cognitive impairment in many studies.

Policy implications

The IMF recommends a comprehensive policy approach that could boost global annual growth by about 0.6 percentage points over the next 25 years, offsetting nearly three-quarters of the demographic drag:

Invest in healthy aging: Countries should prioritize preventive healthcare and initiatives that strengthen physical and cognitive capabilities of older adults. Specific measures include immunization, regular health checks, disease screenings, campaigns to prevent substance abuse, taxation on tobacco and unhealthy food, regulations promoting smoke-free environments, and expanded mental health resources.

Extend working lives: Gradually increase effective retirement ages in line with rising life expectancy. This isn't as simple as just raising official retirement ages — you need to create flexible work arrangements, reducing early retirement benefits, introducing incentives to postpone retirement, and allowing phased retirement options.

Close gender gaps: Implement policies to reduce barriers to female labor force participation, particularly in countries with large existing gaps. These should include improved parental leave systems, affordable childcare options, and flexible work arrangements to improve work-life balance.

The fiscal benefits of doing so would be huge - many countries could not only manage aging-related expenses but also rebuild fiscal buffers for other priorities.

Conclusion

Population aging is inevitable, but its economic impact isn't set in stone. With the right policies supporting healthier aging, extended working lives, and greater workforce participation, countries can significantly offset the demographic challenges they face.

The IMF's message is ultimately hopeful: aging populations don't have to mean economic stagnation. But only if we adapt our policies and institutions to harness the potential of our "silver economy." As populations age, societies that invest in the health and productivity of their older citizens will gain significant competitive advantages in the global economy of the 21st century.

Tidbits

Axis Bank Posts Flat Q4 Profit Amid Higher Provisions, Drop in Trading Income

Source: Business Standard

Axis Bank reported a net profit of ₹7,118 crore for Q4 FY25, nearly unchanged from ₹7,129 crore in the same quarter last year. The flat performance was largely due to a sharp decline in trading income, which dropped to ₹173 crore from ₹1,021 crore, and a rise in loan loss provisions to ₹1,369 crore from ₹832 crore. Net interest income rose 5.5% year-on-year to ₹13,810 crore, while net interest margin stood at 3.97%, up 4 bps sequentially. Fee income grew 12% YoY to ₹6,338 crore, contributing to a 14% sequential rise in non-interest income, which remained flat YoY at ₹6,780 crore. Gross NPA ratio improved to 1.28% from 1.43%. Total advances rose 7.85% YoY to ₹10.41 lakh crore, with retail loans contributing ₹6.23lakh crore. Deposits increased 9.76% YoY to ₹11.73 lakh crore, and the CASA ratio improved to 41% from 39% in the previous quarter.

Air India in Early Talks to Acquire 10 Boeing 737 MAX Jets Amid US-China Trade Tensions

Source: Reuters

Air India is in discussions with Boeing to acquire approximately 10 737 MAX aircraft originally meant for Chinese customers, who are now rejecting deliveries due to ongoing trade tensions between the United States and China, with both countries having imposed tariffs exceeding 100% on each other. The jets are being considered for Air India Express, the airline’s low-cost arm with a fleet of over 100 aircraft. The deal is still in early stages, but if finalized, the planes could be added to the fleet by the end of the year. Boeing CEO Kelly Ortberg confirmed that multiple Chinese customers have opted out of their orders due to tariffs, prompting the company to redirect jets to other clients. Air India has previously accepted white tail aircraft and may use configuration mismatches in these jets to negotiate better pricing. The development follows delays in aircraft deliveries from both Boeing and Airbus, which Air India CEO Campbell Wilson recently described as the airline being a “victim of circumstance.”

Prestige Hospitality Files ₹2,700 Cr IPO Amid Sectoral Momentum

Source: Reuters

Prestige Hospitality Ventures, the hospitality arm of real estate developer Prestige Estates, has filed draft papers for an initial public offering worth ₹2,700 crore (approximately $317 million). The IPO will comprise a fresh issue of shares worth ₹1,700 crore and an offer for sale by the parent company amounting to ₹1,000 crore. Prestige’s move also aligns with its broader capital-raising plans, previously reported to be in the ₹2,000–3,000 crore range. Despite ongoing market volatility, about 67 companies have raised over $2.32 billion in IPOs so far this year in India, according to data compiled by LSEG. Lead book-running managers for the Prestige Hospitality IPO include J.M. Financial, CLSA, J.P. Morgan, and Kotak Mahindra Capital.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Prerana.

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉