Why LG India’s IPO is Making Headlines!

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

LG India’s ₹15,000 Crore IPO: What’s the Big Deal?

Why China’s Economy Is Slowing Down Again

LG India’s ₹15,000 Crore IPO: What’s the Big Deal?

LG Electronics, a Korean company, is planning to list its Indian subsidiary. They’re looking to raise around ₹15,000 crores through a 100% Offer for Sale (OFS). This means LG’s parent company in Korea will sell part of its stake in the Indian business and keep the money. None of the funds from this sale will go to LG India itself.

LG India is one of the most well-known names in home appliances and consumer electronics. If you own a washing machine or microwave, there’s a good chance it has LG’s logo on it.

The IPO documents provide an interesting look into how LG operates and give us valuable insights into the overall industry. We’ve gone through all 456 pages so you don’t have to. Let’s start with the basics.

LG is the second-largest player in the consumer electronics market by revenue, coming in just after Samsung.

When compared to other listed companies, LG India stands out as the biggest player by revenue, ahead of Havells and Voltas.

LG India is the top brand in washing machines, microwaves, and compressors. In the refrigerator category, it’s competing closely with Samsung for the number one spot. While Voltas sells more air conditioners overall, LG dominates the premium segment with a 31% market share.

Here’s where it gets interesting: India still lags far behind when it comes to owning home appliances.

Only about 40% of households have a refrigerator. For washing machines, it’s even lower—around 20%. And microwaves? Less than 5%.

Now, compare this to countries like China, where these appliances are found in most homes, and it’s easy to see why companies like LG are so optimistic about the Indian market.

So, where does LG India make most of its money?

Last year, LG India brought in about ₹20,000 crores in revenue, and a big chunk of that—around 70%—came from home appliances and air solutions. This includes products like refrigerators, washing machines, air conditioners, and smaller items like microwaves.

Breaking it down further, refrigerators made up about 30% of the revenue, washing machines another 20%, and air conditioners also contributed around 30%. The remaining 20% of the revenue came from the home entertainment division, which includes TVs and related products.

What’s interesting is how LG’s premium products play a big role in driving profits. While affordable models attract more customers, it’s the high-end products with better margins that really make a difference to the company’s bottom line.

Selling electronics in India isn’t just about the products—it’s equally about distribution. LG has built a network that covers both the organized and unorganized sectors, each with its own unique challenges and opportunities.

The company runs exclusive LG brand stores, mostly in urban and semi-urban areas. It also partners with multi-brand retailers like Croma and Reliance Digital, which help LG reach a wider and more varied customer base. However, these stores are highly competitive, with LG competing alongside brands like Samsung and Whirlpool for customer attention.

E-commerce platforms like Amazon and Flipkart are becoming an increasingly important sales channel. While the IPO document (DRHP) doesn’t specify the revenue from online platforms, it’s clear that this segment is growing fast.

The real challenge lies in the unorganized market, which dominates rural and small-town India. Local shops often sell cheaper, unbranded products, making it tough for organized players like LG to compete on price. To address this, LG offers affordable entry-level models and backs them with strong after-sales service.

According to Redseer’s analysis, the unorganized general trade sector is expected to shrink from 40% to 32% by 2028, while organized online channels, like e-commerce, are projected to grow from 38% to 45%.

Most of what LG sells in India is made locally. The company operates two major factories—one in Noida and another in Pune. These facilities not only meet domestic demand but also help LG cut costs by reducing imports.

LG is planning a big expansion and intends to set up a new manufacturing plant in Andhra Pradesh. It’s reasonable to assume this move is aimed at taking advantage of the government’s Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme. The PLI program is designed to encourage domestic manufacturing by offering financial incentives to companies and reducing reliance on imports.

Why China’s Economy Is Slowing Down Again

Let’s start with the latest numbers: China’s consumer inflation fell to just 0.2% in November, down from 0.3% in October and far below the expected 0.5%. This isn’t just a small drop—it points to a deeper issue with weak domestic demand.

Chinese households, still dealing with the aftermath of the property market slump and feeling uncertain about the economy, are holding back on spending. Instead of buying more, they’re saving and focusing on paying off debt, especially mortgages.

What’s even more worrying is what’s happening at the producer level. China’s producer price index, which tracks factory gate prices, has been in deflation for 26 straight months, dropping by 2.5% in November. This ongoing deflation creates a challenging cycle: as Chinese goods become cheaper, they flood international markets, worsening trade imbalances with countries like the United States. In fact, China’s trade surplus has now grown to over $870 billion in the past year—almost 5% of its GDP.

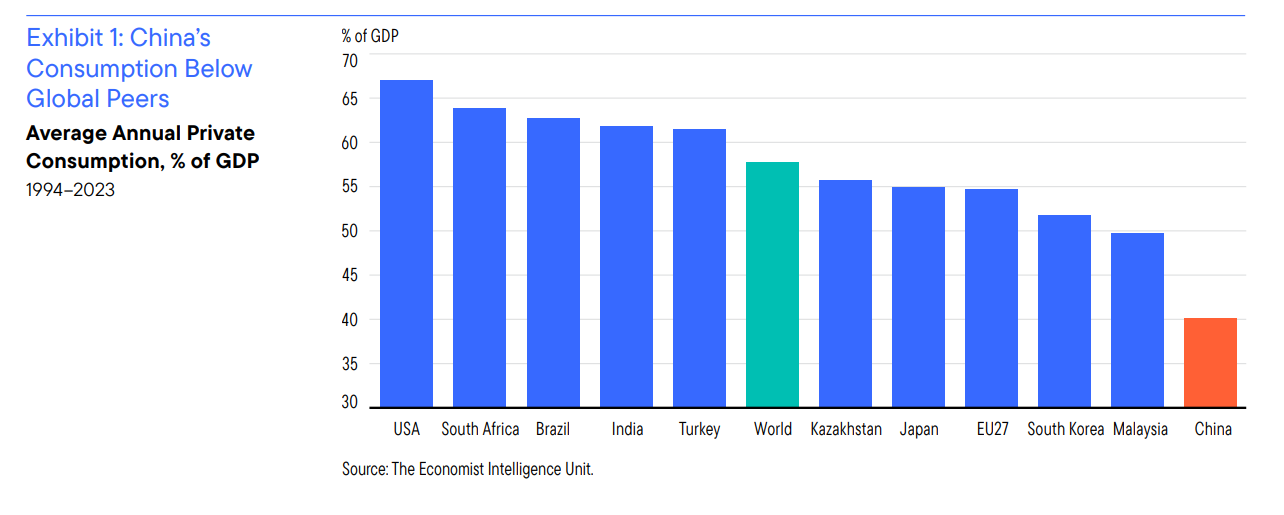

Let’s take a step back to understand the bigger issue. China’s economy has long relied on a model that prioritizes investment and exports over household spending. The numbers make it clear: household consumption accounts for just 39% of China’s GDP, compared to a global average of 58%.

Think of it this way: China has built an economy that’s amazing at producing goods but struggles to create enough domestic demand for those goods. This leads to a cycle where excess production causes deflation at home, forcing companies to export more. That, in turn, leads to trade tensions with other countries.

What makes this problem even harder to solve is that 60–65% of China’s total savings are held by the top 10% of households. This means that even if China finds ways to increase household income or improve the social safety net to encourage spending, it wouldn’t have a big impact. Lower-income households don’t have much savings to begin with, so they simply can’t spend more.

China has tried to tackle this with stimulus measures, but these efforts have been fairly limited. For example, the recent fiscal package announced at the National People’s Congress didn’t do much to excite markets. Small online voucher programs and modest fiscal support haven’t made a noticeable difference in consumer spending. Analysts at UBS have pointed out that there’s no quick fix here, and they expect weak consumption to continue into 2025. They believe markets have been overly optimistic about how quickly China can shift away from its investment-driven growth model.

Goldman Sachs has a different take. They argue that new U.S. tariffs—around 20% under the Trump administration—could actually push China to rely more on domestic consumption. The idea is that as external demand decreases, China might be forced to stimulate spending at home.

But economist Michael Pettis has a strong counter-argument. He says China’s trade surplus exists because the country produces more than it consumes or invests—it’s simple math. Unless tariffs somehow change how income flows to Chinese households, they’ll only shift trade patterns without solving the core issue.

Both Goldman Sachs and UBS predict new tariffs under the Trump administration. Goldman estimates a 20 percentage point increase in tariffs on Chinese goods, while UBS expects a smaller rise, potentially from 10%. They estimate these tariffs could lower China’s GDP growth by up to 1% in a worst-case scenario. However, some argue these forecasts may be too pessimistic. Many companies have already set up alternative trade routes since the first trade war, rerouting goods through countries like Vietnam or Mexico before they reach the U.S. This could soften the impact of any new tariffs.

Deflation in China isn’t just a problem for its economy—it’s causing global tensions too. Falling prices on Chinese exports are making trade imbalances with key partners like the United States even worse.

With weak demand at home, Chinese companies are relying more and more on exports. This has sparked worries about overproduction in industries like electric vehicles and solar panels. These concerns are fueling calls for new tariffs in the U.S. and Europe.

This situation is particularly tricky because both sides have valid concerns. The U.S. is worried about China’s industrial overcapacity flooding global markets, while China needs to keep its export growth strong as it works on increasing domestic consumption. This isn’t just a trade issue—it’s about fundamental differences in how the two economies are structured.

Looking ahead to 2025, ING predicts that China’s GDP growth will slow to 4.6%, with consumer spending remaining weak. To truly break this cycle, China would need to make major changes to how income is distributed—getting more money into households and building their confidence to spend. Without these reforms, China will stay stuck in a loop where it produces more than it consumes, causing deflation at home and trade tensions around the world.

Tidbits

The government has appointed Revenue Secretary Sanjay Malhotra as the 26th RBI Governor for a three-year term. A seasoned IAS officer, Malhotra brings deep experience in public finance, having led GST Council discussions and helped increase India’s tax collections. His term begins at a time when the economy faces challenges like high inflation and pressure on growth.

The government also plans to phase out Sovereign Gold Bonds by the financial year 2026 to reduce fiscal liabilities, which have reached ₹4.5 trillion. As this happens, retail investors might shift to gold ETFs, with the government focusing on fiscal consolidation and lowering gold import duties.

Meanwhile, Foreign Portfolio Investors (FPIs) pumped ₹24,454 crore into Indian markets during the first week of December 2024, reversing the heavy outflows seen in October and November. This renewed investment shows growing confidence in India’s markets, with sectors like IT and banking benefiting from better valuations.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Kashish

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉 Join the discussion on today’s edition here.

People in villages have washing machine and fridge now,the data must be incomplete,as is in most cases in indian survey, I am sceptical over tv data as well, I don't see the numbers add up