Why is everyone talking about DeepSeek?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The mysterious AI from the East

EMS in India: A Short-Term Spike or Long-Term Shift?

The mysterious AI from the East

DeepSeek has become the biggest conversation in AI.

This didn’t come out of nowhere. For a long time, the company was grinding quietly in the dark, innovating and overcoming barriers. In Silicon Valley circles, it was known as the “mysterious force from the East”. Anthropic co-founder Jack Clark had commented, last May, that DeepSeek hired “inscrutable wizards”. The company wasn’t famous, but those in the know spoke of it with respect.

Last week, the world saw why.

Murmurs of its prowess began late in December when DeepSeek came out with its V-3 model. It was surprisingly advanced — as good as OpenAI’s cutting-edge GPT-4o, with a lot of incredible technology under the hood. But it didn’t make much of a flutter outside tech circles. We had all been spoiled by all the excellent models we already had. Then, late in January, it made another leap. It came up with a rival to OpenAI’s “reasoning” model — ‘O1’. This was huge. Nobody else in Silicon Valley had quite cracked reasoning yet.

When people started using it — and saw just how good it was — the hype cycle took off.

More impressively, it got there at a fraction of the cost. It trained its models for a mere $5 million, even as American AI companies were draining hundreds of millions of dollars. It did so without the world’s best AI chips — which all its American competitors had easy access to. It did the equivalent of making an F1 racecar with Maruti spare parts. And the kicker? It’s open source. Anyone can take it, modify it, and build upon it.

This is a big moment. Let’s dive in.

The old world

For most of its short history, the world’s gen-AI ecosystem all but sat in America. The big ‘foundation models’ all came from American AI labs — OpenAI, Google, Anthropic and Meta. They were all backed by the richest companies in the world. And they were all built on top of a world-beating hardware ecosystem, led by the incredible Nvidia — that was making generational leaps in technology every year.

Because of this, the world’s AI ecosystem was on a very peculiar trajectory.

See, the AI ‘business’, at its heart, requires three key inputs: (a) computing power, (b) data, and (c) human genius. Silicon Valley was an endless fountain of all three.

In just the last few years, Nvidia has been speed-running through decades-worth of innovation. The capacity of its chips has been growing exponentially — even faster than Moore’s law suggested. Big tech businesses — which backed the major AI labs — had spent their entire lives creating huge repositories of data, which were opened up for AI. And few places in the world have as much human genius as Silicon Valley.

Behind all of this was the valley’s incredible VC ecosystem, which brought in billions of Dollars for these AI labs.

And so, AI labs found themselves in a business utopia — one where you could spend infinite money, resources were everywhere, and profits didn’t matter. All that mattered was doing good work, fast. Top AI labs were comfortable losing more than a billion Dollars a year in this race. Their models were — and are — magical. But they were made with no regard to costs. They were all meant to consume as much computing power as possible. To be fair, it wasn’t clear that things could be done any other way.

This all started as a humanitarian project. OpenAI, for instance, started as a non-profit that wanted to create AGI — the sentient computers that you’d see in science fiction movies — for the good of humanity. But as competition heated up, they all turned secretive, hiding their methods and models from one another. AGI, like everything else, became a race. Meta was the only one that went against this grain, opening its Llama model to others. But it was only trying out an old Silicon Valley trick — of giving something away for free, just to make people dependent on you. This was exactly what Android had done a generation before.

It wasn’t just individual companies. America, too, was trying to lock AI within its borders. President Biden, before leaving office, crippled the world’s ability to access cutting-edge AI tech. Meanwhile, America was ramping up its capabilities at a ludicrous pace. At President Trump’s inauguration, for instance, OpenAI announced a half-a-trillion-dollar investment into a new data center. That is, incidentally, more than Norway’s entire GDP.

America was the only country in the global AI contest, and it was winning by default. Others were destined to fall behind.

Except… DeepSeek came and trashed this script.

DeepSeek makes a splash

DeepSeek is a profoundly odd company.

It really began as a side project (much like Markets is, wink wink 😀) for High-Flyer, a hedge fund that was using GPUs to create trading algorithms. Its founder, Liang Wenfeng, has been an AI nerd since college. He first used machine learning to earn billions trading stocks. But with time, he began pulling in people for a side project — getting to AGI.

DeepSeek had no right to succeed. Despite its billionaire founder, it was much poorer than its Silicon Valley counterparts. More importantly, America had banned the best AI chips—Nvidia’s H100—from reaching China.

But necessity is the mother of invention.

Instead of H100 chips, Nvidia was selling H800 chips to China. These were powerful, but they were designed not to do AI work. This is where DeepSeek’s ‘inscrutable wizards’ stepped in. Using “assembly language” — which is only slightly simpler than coding using just 1s and 0s — they completely changed what these chips did, making them AI-capable. It was a ridiculous feat. These chips were still nowhere near as good as what the Americans had easy access to, but they’d have to do.

Then, they played around how their AI worked, so that they could do everything the Americans could, but with far worse chips. For instance:

They broke their AI model down into tiny, purpose-specific models—a “mixture of experts"—where only parts of the model had to work at once. This prevented their chips from handling the whole load at once.

They came up with unique ways of compressing what the model had to remember in order to work, allowing it to pull the same feats of reasoning with 5% of the memory.

They squeezed every bit of data in the model into half the space, allowing their GPUs to become twice as efficient.

…and so on.

Instead of training a model on mountains of data, an extremely expensive task, DeepSeek allegedly asked models like ChatGPT 4o thousands of questions and trained itself on those answers. This process, called ‘distillation,’ allowed it to gather the best insights of rival AI systems for a fraction of the cost.

Either way, by the end of it all, DeepSeek had created something profound — a cutting-edge AI system that was almost twenty times as efficient as any of its rivals.

And then, they gave it all away. They opened their model to the public under an ‘MIT license’ — with no strings attached. You and I can download it, modify it however we like, and maybe even use it to run a rival AI business. For developers, using DeepSeek is now 200 times as cheap as rivals like Anthropic. They explained all their innovations in detailed papers, which they released for free. Ironically, in an era where Americans were trying to bottle AI up, a bunch of Chinese geeks set it free.

A new world

Make no mistake — this is a huge development.

It’ll force a fundamental re-think among American AI labs. They still have significant advantages — in terms of money, compute, and personnel — but they’ve been put on the backfoot anyway.

DeepSeek has cracked open a new vector of competition: one of the ways in which the architecture of one’s model is efficient. This simply wasn’t the case before. It was as though Saudi Arabia had invented motorcars, and so, they all had a mileage of one. Expect American AI labs to try and quickly play catch-up while hiding their best models to prevent more distillation.

Things can go two ways from here — and it really depends on how much better AI models can potentially get. If there’s a lot more room for improvement, American labs will double down, spend more, and try to pull as far ahead of DeepSeek as they can. If there isn’t, however, AI may get ‘commoditized’. That is, if users think different AI models are equally good, they’ll turn to the cheapest model available. And that will upset the industry’s dynamics completely. The era of “more is better” will officially be over.

Because DeepSeek is incredibly cheap, it’s going to be much easier for other businesses to plug in and build on top of it. That means that you might see a lot more AI-based products, with DeepSeek at the back end.

DeepSeek’s open-sourcing can have profound implications, of a sort we can’t really predict. With that, AI has basically become a lego-block that anyone can play with. What people make with it is anyone’s guess. Some hobbyists, for instance, have already cut the model down to 20% of its size — making it small enough to run on your laptop without accessing the internet. This is just the beginning.

The one part of the American AI ecosystem that might be relatively safe, though, is Nvidia. Of course, with more efficient AI systems, the amount of computation you need for each use will go down. Doesn't that mean there's going to be less demand for chips?

Not necessarily, because of Jevons paradox.

Imagine, once again, that motorcars had a mileage of one. Very few people would drive - it would simply not be affordable! Petrol demand would be low, in this world. Now, imagine someone came up with a new, efficient car - with a mileage of 20. Oil refiners would be worried because the per-kilometer demand for petrol would drop. At the same time, though, far more people would suddenly find driving affordable. You might see an explosion in automobile demand. And with that, the total demand for petrol could go up, not down!

Nvidia’s story might look like that of these oil refiners. A post-DeepSeek world might require more computing, not less.

What does all of this mean for India? That’s impossible to predict — much like nobody could tell you, back in 2007, what smartphones would mean for India.

But there’s definitely a bigger lesson here: if you want to become a technological leader, you need to invest in developing human brains, not on hoarding technology. Human ingenuity can upend all kinds of carefully laid plans. This happens all the time — in business, in politics, in warfare, and everywhere else. And it’s just happened again: the combined might of the big-tech industry and the US government can be neutered by a bunch of Chinese math wizards.

As K wrote recently: “The secret sauce lies not in model weights, but in biological brains.”

EMS in India: A Short-Term Spike or Long-Term Shift?

India’s Electronics Manufacturing Services (EMS) sector is in the midst of a significant and transformative phase. This isn’t just a short-term trend; it could be something more enduring. For investors and market watchers, it’s important to understand what’s going on.

Let’s start with some context. The EMS industry focuses on manufacturing electronic products and components, including printed circuit boards (PCBs) and displays, which are essential for a wide range of electronics. These components are then assembled into products like smartphones, televisions, and even advanced equipment for healthcare and aerospace.

However, in India, most companies in this space are still primarily assemblers. They focus on designing, producing, assembling, and repairing electronic products for clients in industries like smartphones, laptops, and telecom equipment. While some players are beginning to invest in higher-value areas like chip manufacturing, this is still at a very early stage. For now, Indian EMS companies are far from competing in the more advanced parts of the global electronics supply chain.

That said, the EMS sector is being touted as India’s next major growth story. Recently, three of the country’s leading EMS companies—Dixon Technologies, Kaynes Technology, and Amber Enterprises—released their quarterly financial results. As key players in this space, their performance offers valuable insights into the sector’s current state and potential.

Starting with Dixon Technologies, they posted an impressive 117% year-on-year (Y-o-Y) increase in revenue, with profit after tax (PAT) rising by 124% Y-o-Y. On a quarter-on-quarter (Q-o-Q) basis, however, revenue declined by about 9.37%, and PAT fell by nearly 48%.

A major growth driver for Dixon has been mobile phone manufacturing. The company claims it can now produce over 60 million smartphones annually and has begun exporting to markets like Africa. Looking ahead, Dixon plans to make a significant investment in display fabrication, a project that could cost a few billion dollars. Government incentives are expected to cover up to 70% of this capex, which Dixon believes will help push its margins into double-digit territory. By developing in-house capabilities for components like displays and PCBs, they aim to reduce reliance on imports and add more value locally.

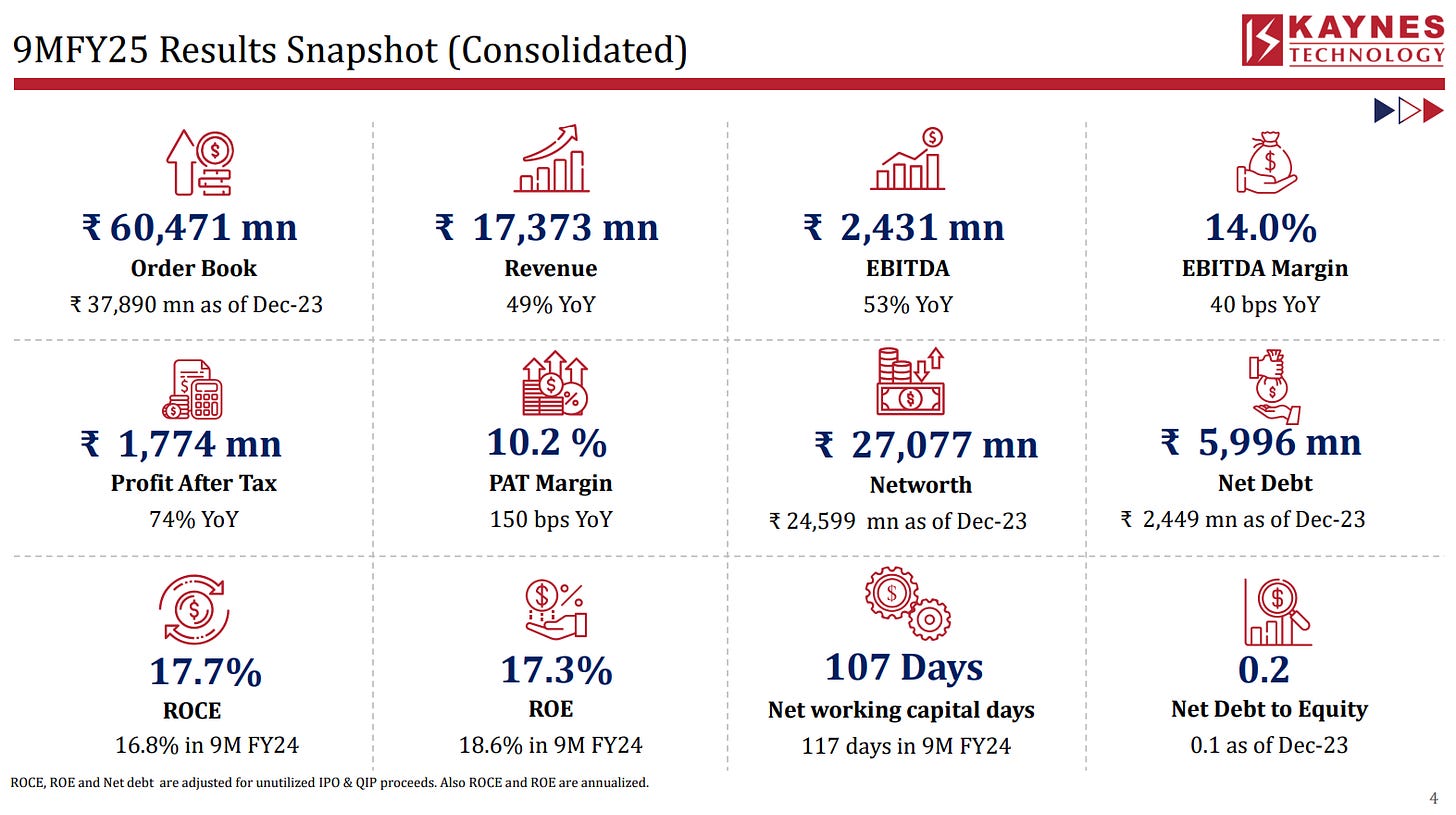

Next, Kaynes Technology reported a 30% increase in annual revenue. Although some orders were delayed this quarter, the management remains optimistic about the industry’s outlook.

In a recent interview, Kaynes’ leadership outlined plans to expand geographically and enhance their technological capabilities. Kaynes specializes in high-tech products for sectors like aerospace, EVs, and medical devices. They are also exploring opportunities in semiconductor assembly and testing—an area crucial for nearly all electronic products—which could strengthen India’s position in the global electronics supply chain.

Amber Enterprises, another key player, saw a 65% Y-o-Y increase in revenue. Profits, which were negative last year, have also turned positive.

Amber, best known for air conditioners and related components, is now leveraging its growth to diversify into new products like advanced circuit boards. Similar to Dixon and Kaynes, Amber is investing in local component manufacturing to boost profitability and reduce import dependence.

A major catalyst for this rapid growth is the Indian government’s Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, which offers financial incentives to electronics manufacturers that meet certain production targets. This initiative has encouraged companies to set up or expand factories in India, driving investments, job creation, and increased manufacturing activity.

Global trends are also favoring India. Rising costs in China and geopolitical tensions have prompted international firms to diversify their supply chains.

As a result, major players like Apple and Foxconn have expanded their production in India. The country’s large workforce, relatively low labor costs, and supportive government policies have made it an attractive alternative manufacturing hub.

India’s electronic exports have rebounded strongly after a brief slowdown. In December, exports grew nearly 40% Y-o-Y, following close to 50% Y-o-Y growth in the two preceding months. Electronic exports now contribute 10% of India’s total merchandise exports, with monthly export values reaching around $3.5 billion. Since 2019, electronic exports have tripled, while overall exports have grown by just over a third.

Despite this momentum, challenges remain. Many EMS companies still depend heavily on imported high-tech components, especially semiconductors, making them vulnerable to global supply chain disruptions. Expanding production lines and investing in new technologies require significant capital, which can be difficult for smaller firms to access.

Additionally, the EMS business is inherently fragile due to razor-thin profit margins—often under 10%. These companies rely on large volumes to stay profitable, meaning any disruption in production or input cost increases can quickly erode margins.

High valuations have also raised concerns. EMS stocks in India often trade at lofty price-to-earnings multiples—sometimes as high as 70x to 100x earnings. This leaves little room for error, as even a minor slowdown in growth or a hit to margins could lead to sharp stock corrections. While the long-term growth potential is promising, investors should be prepared for volatility in the short to medium term.

Despite these hurdles, the future of India’s EMS sector looks bright. Growth is expected to come not just from increased production of smartphones and TVs but from the development of a more comprehensive electronics ecosystem within the country. This means more local jobs, greater self-reliance, and a stronger position in the global electronics industry.

For leading companies like Dixon, Kaynes, and Amber, the outlook remains positive, though the challenges we discussed cannot be ignored. However, there’s clearly a significant opportunity for these players to expand, enter new markets, and strengthen their presence in key areas of the industry.

Tidbits

Indian jewellers are bracing for a surge in Gold Metal Loan (GML) interest rates as US tariffs disrupt the global bullion market. Currently at 1.5-2%, GML rates could climb to 3-4% or even 5-6% post-February 20, as authorized Indian banks adjust to rising costs from international bullion suppliers like JPMorgan and HSBC. With the Reserve Bank of India authorizing 14 banks to import gold, including Kotak Mahindra Bank and ICICI Bank, the expected hike will primarily impact jewellers’ cash flow and hedging strategies, rather than end consumers.

Hindustan Zinc Ltd, India’s largest zinc and silver producer with a market cap of over ₹18,000 crore, has put its demerger plans on hold. The company aims to diversify into critical minerals like vanadium and tungsten and expand into gold and copper mining. The government, holding a 27% stake, has raised objections to the demerger, emphasizing the company’s strong performance as a single entity. While the demerger is delayed, Hindustan Zinc is prioritizing vertical integration into non-zinc mining activities, which may take 3–5 years to operationalize.

The Adani Group, via its Dubai-based affiliate Renew Exim DMCC, is set to acquire up to 72.64% of ITD Cementation India Limited (ICIL) in a ₹5,758 crore deal. This includes an initial purchase of 46.64% (8 crore shares) and an open offer for an additional 26% (4.46 crore shares) as per SEBI regulations. The acquisition enhances Adani’s EPC capabilities and positions it strongly in India’s infrastructure growth story.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Anurag

🌱One thing we learned today

Every day, each team member shares something they've learned, not limited to finance. It's our way of trying to be a little less dumb every day. Check it out here

This website won't have a newsletter. However, if you want to be notified about new posts, you can subscribe to the site's RSS feed and read it on apps like Feedly. Even the Substack app supports external RSS feeds and you can read One Thing We Learned Today along with all your other newsletters.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉 Join the discussion on today’s edition here.