Why is China dumping everything everywhere?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts and video on YouTube.

Today, we look at 4 big stories:

Trade wars

Private sector is hot for India once again!

The past, present and future of the Indian economy

Why is the RBI governor worried about deposit growth

Trade wars

India recently launched an anti-dumping investigation into imports of steel products from Vietnam. The concern is that Vietnam has been dumping cheap steel into the Indian market, which has alarmed domestic players like JSW Steel and ArcelorMittal Nippon Steel. These companies are worried that these low-cost imports are hurting their business by making it difficult to compete, as they can't match the prices set by Vietnamese steel makers.

Source: CRISIL

Specifically, India’s investigation targets Hot Rolled Coil (HRC) steel imports from Vietnam. HRC steel is widely used in manufacturing car parts, building structures, and machinery. On the surface, this might seem like a step in the right direction, but the reality is that India doesn't import much of its steel from Vietnam. The bigger issue is China.

China is a major supplier of steel to India, as it is to many other countries. According to S&P Global, in July alone, Chinese steel was expected to make up 73% of India's total steel imports.

Source: S&P Global

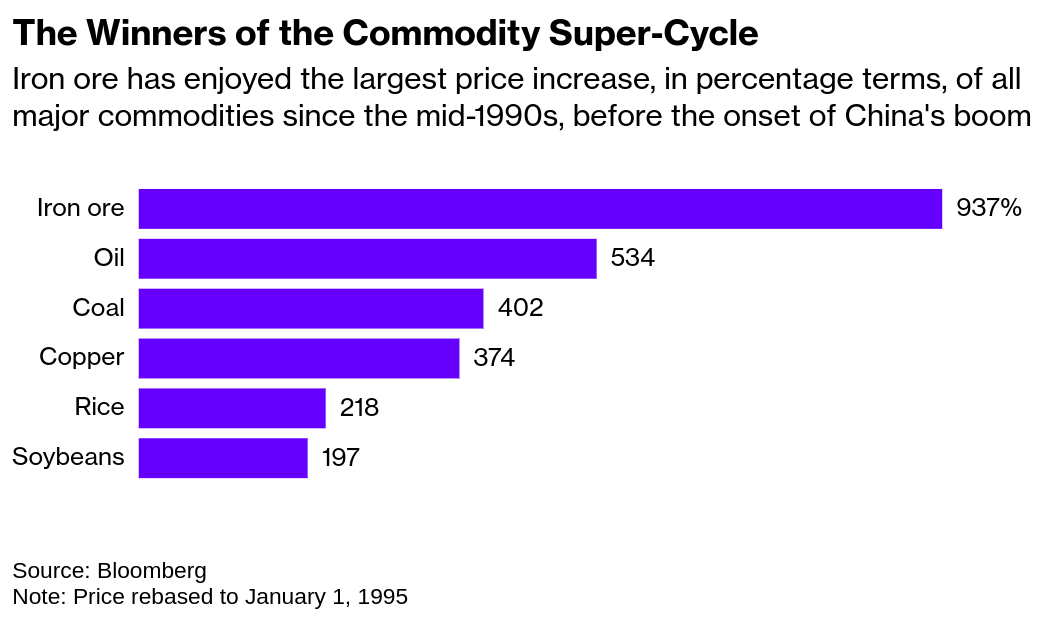

Over the past few decades, China transformed into an economic powerhouse largely due to massive government investments in infrastructure. China poured enormous sums into building highways, railways, power plants, heavy industries, and vast urban housing projects. This rapid industrialization turned China into an export giant and the "world's factory." To fuel this growth, China required vast amounts of steel, which in turn drove up global iron ore prices over the last 25 years.

Source: Bloomberg

However, the situation in China is shifting. The Chinese economy is no longer expanding at the breakneck pace it once did, which means the country doesn't need as much steel as before. This has led to excess steel production, and China now needs to find ways to offload this surplus.

The world’s largest steel producer, based in China, has even described the current conditions in China's steel sector as a "harsh winter," one that will be "longer, colder, and more difficult to endure than expected." This is deeply concerning. So, where does all this extra steel go? As we mentioned earlier, they dump it in other countries.

The problem with dumping is that it can lead to global dependency on a single country. This could give China even more power in global trade, which poses significant risks. Why? Because China’s dominance in global trade means it could start using its power to pressure other countries. For instance, if China decided to stop exporting certain materials or products, countries that heavily rely on these imports would face serious challenges. Additionally, because China can produce more than it needs, it can sell products at low prices, potentially driving domestic companies out of business because they can’t compete.

We’re already seeing the impact of Chinese steel imports on prices. In mid-July, Chinese Cold Rolled Coil (CRC), used in making home appliances, car body panels, and furniture, was sold to Indian importers at $610 per metric ton. Even after adding a 7.5% import tax, Chinese steel was still over ₹4,000 per metric ton cheaper than the same type of steel made in India.

It’s not just India feeling the pressure; other countries are reacting too. Brazil, for instance, has set limits on how much steel can be imported from China. If more steel is imported than allowed, the extra steel will be taxed at a higher rate. Brazil is doing this to protect its local steel industry from being overwhelmed by cheap Chinese steel.

Source: Rhodium

This trend isn't confined to the steel industry. The U.S. and Europe have been imposing tariffs on Chinese goods, especially in sectors like electric vehicles, to shield their own industries from being flooded with cheap imports.

For example, in the U.S., President Biden recently announced a 100% tariff on electric vehicles, a 50% tariff on semiconductors, and a 25% tariff on EV batteries imported from China. Europe has followed suit, imposing extra temporary tariffs of up to 38% on electric vehicles imported from China.

This is a fascinating trend, and we’ll be diving deeper into it in the future.

Private sector is hot for India once again!

Most of us hear the term 'GDP' almost every day, but not many of us really know what it means. Simply put, GDP measures the amount of economic activity in a country. It's made up of a few key components:

1. What the country’s people spend.

2. What its government spends.

3. What people from abroad spend in the country.

4. And finally, investments.

A big part of this GDP calculation is investment. Investments are crucial because they act as a leading indicator of the economy. Essentially, the higher the investment, the more growth we can expect in the future.

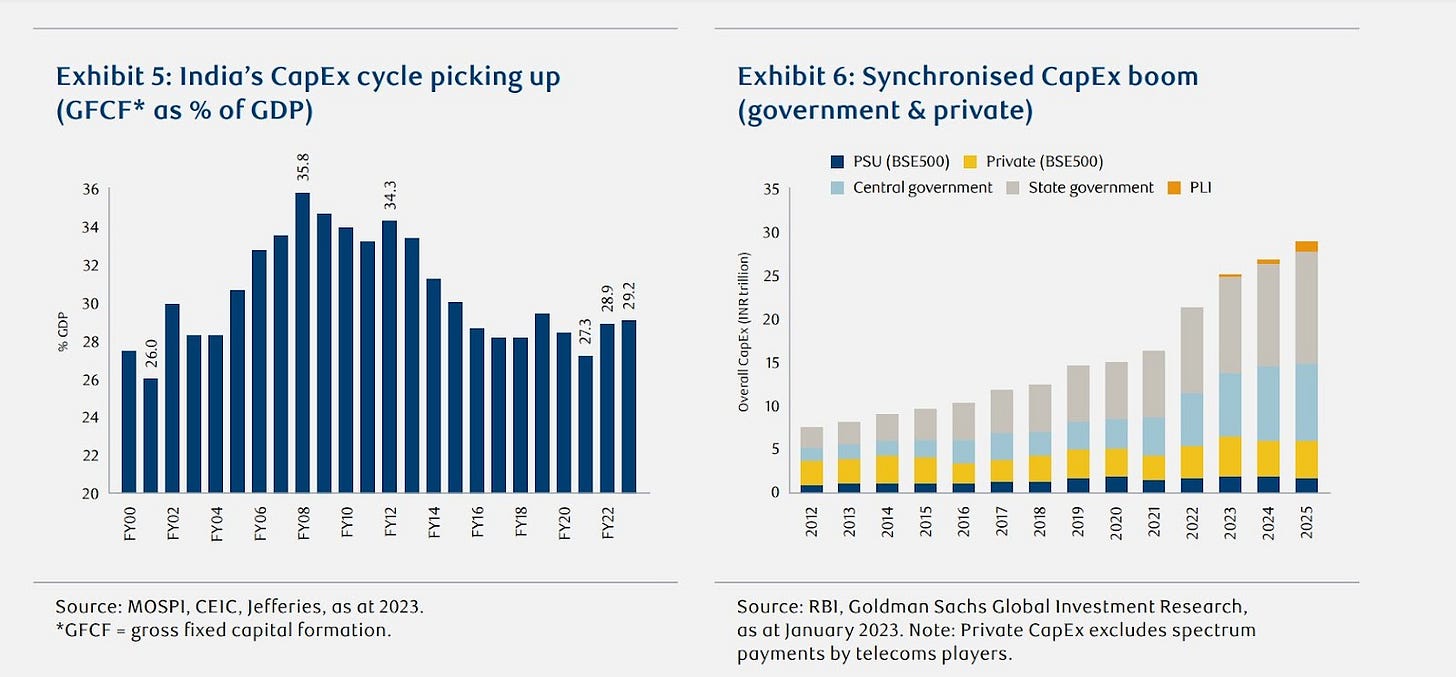

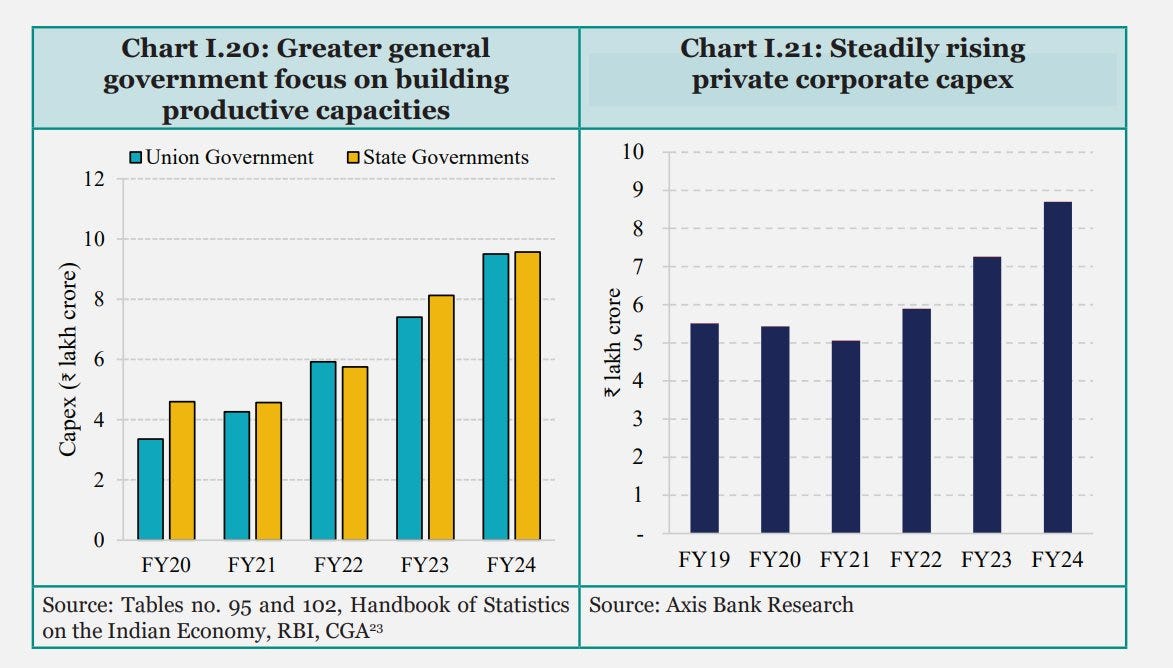

Now, these investments can come from either the private sector or the government. One thing the current NDA government has done well is ramping up infrastructure-related investments across the country. In fact, over the past few years, government capital expenditure (capex) has been a major driver of our economic growth, while private investments have barely budged.

But there's an interesting shift happening. Even though government investments are increasing, there's some reallocation going on. If we break it down, while direct investments by the government are on the rise, Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) or public sector companies are cutting back on their capital expenditure—the money they spend on expanding capacity, building new plants, etc.

According to a report by Motilal Oswal, PSU investments have dropped from about 2.3% of the country’s GDP in FY2020 to just 1.2% in FY2023. To put it in perspective, PSU capex was only 40% of the central government's capex in FY24, whereas about 10 years ago, it was almost 150%.

Source: Motilal Oswal

This suggests that a lot of government investment is now being made directly, instead of being funneled through PSUs. This could be intentional, possibly because PSUs are largely inefficient, or maybe there’s another reason—we can’t be entirely sure.

In an ideal scenario, government infrastructure investments should be followed by private investments. Think about it: if the government builds a road from point A to point B, it’s only truly beneficial for the economy if people on the A side can start trading more easily with people on the B side. So, you’d expect that after the government’s investment, a lot of private investment would follow to facilitate this trade. But strangely, since 2011, that hasn't been happening.

Until 2011, private investments in India were quite strong and consistently rising. They grew from around 10% of GDP in the 1980s to around 27% in 2007-08. But after 2011-12, they started dropping almost in a straight line. By 2020-21, private investments had fallen to just 19.6% of GDP.

Source: USMutual funds

Some economists suggest that this drop in investments could be due to low private consumption expenditures in India. But there might be another reason at play. In one of our older episodes, we referred to an editorial by economists Josh Felman and Arvind Subramanian. To give you a quick summary, they argued that while investing in India can yield great returns, it also comes with unique risks.

They pointed out that in India, there’s always a chance that your investment could suddenly lose value because government policies might shift against you. Even worse, this risk isn’t just for the future; it could also apply retrospectively! Something similar happened with Vodafone and a few other companies in 2011, and that very possibility might be scaring private investors away from putting their money into India.

But there’s some good news. According to a recent report from the RBI, private investments in the country seem to be picking up again. In FY23-24, private companies managed to raise ₹5.6 lakh crores from banks, IPOs, and external borrowings for 1,505 projects, compared to ₹3.5 lakh crores in FY22-23 for 982 projects. That’s pretty encouraging, especially considering how much people have been lamenting the lack of private investment.

Now, it’s important to note that not all of this ₹5.6 lakh crores will be spent in the same financial year. These investments typically happen in phases over multiple years. Of this total amount, the expected capex for this financial year is set to increase significantly from ₹1.59 lakh crores in 2023-24 to ₹2.45 lakh crores in 2024-25.

But remember, these are just investment intentions, not final investments. That means some of these investments might not materialize. There’s also the fact that project estimates can be revised up or down, or there could be significant delays—this is India, after all.

Still, investment intentions are an important early indicator. They give us a directional sense of whether the private sector is even thinking about investing. So, fingers crossed.

Source: Economic Survey

The past, present and future of the Indian economy

C. Rangarajan is one of the most distinguished economists we've ever had. He's held various important roles throughout his career, including serving as an economic advisor in the UPA government, governor of multiple states, a member of parliament, and perhaps most notably, as the governor of the Reserve Bank of India from 1992 to 1997. This was a critical period when India was grappling with massive economic challenges and was in the midst of liberalizing its economy and opening up to foreign investments.

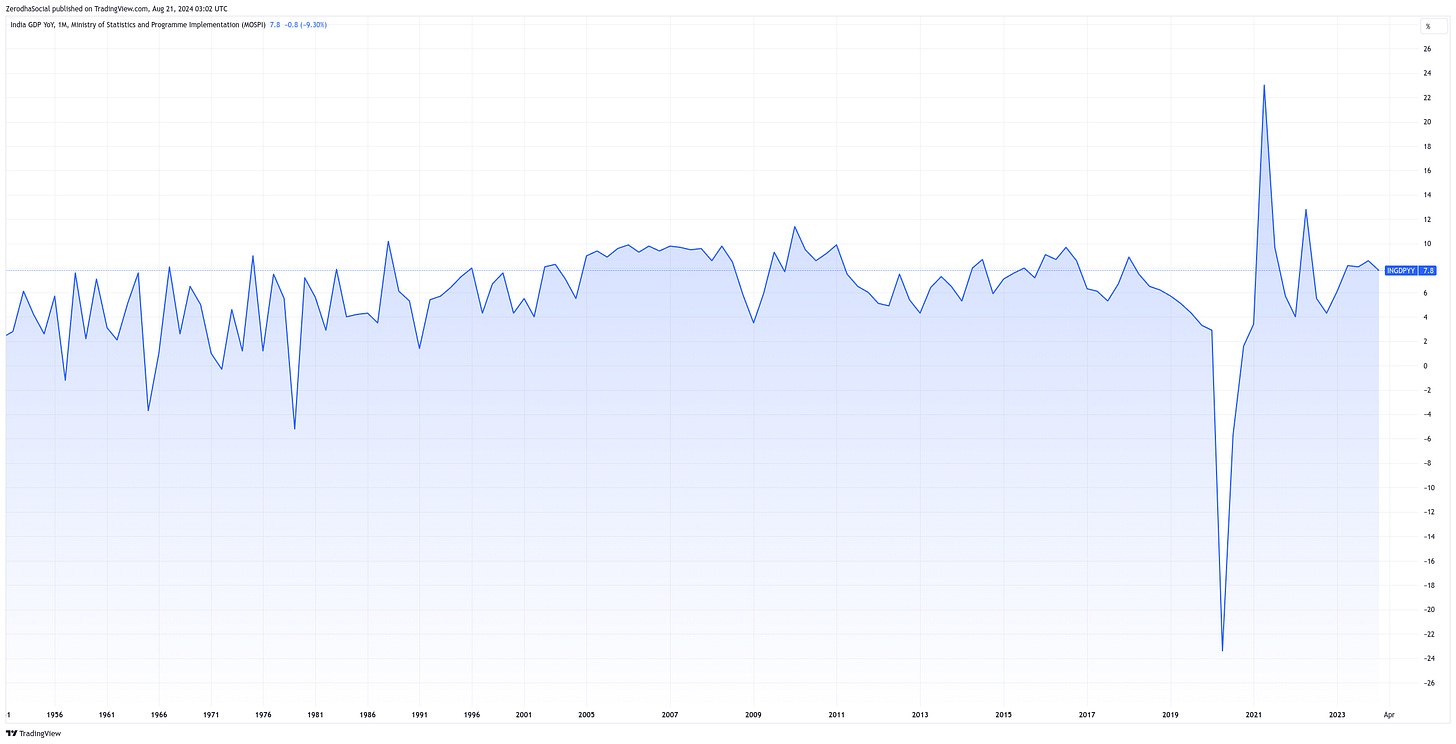

Now, at 91 years old, Dr. Rangarajan has witnessed the entirety of independent India's economic journey. On Independence Day, he gave an insightful interview to CNBC TV18, where he shared some fascinating perspectives on our economic history and the current landscape. We found a few points particularly interesting:

When discussing the history of economic reforms, Dr. Rangarajan noted that in the 1950s, India, as a poor, underdeveloped country, had no clear path for economic development. The Indian economic strategy back then was built on four key pillars:

1. Increasing savings and investment rates.

2. A dominant role for the state in the economy.

3. An import substitution policy—essentially trying to manufacture everything domestically.

4. A focus on industrialization, particularly heavy industry.

However, by the 1970s, it became evident that this strategy wasn't working. India needed to change its economic approach, but policymakers missed the opportunity. It took another two decades before the necessary and harsh reforms were implemented.

By 1991, India faced a severe balance of payments crisis. To put it simply, by the end of 1990, India had only enough foreign exchange reserves to cover three weeks' worth of imports. In contrast, today, India has forex reserves of around $670 billion. Back then, India was forced to pledge its gold, devalue the rupee twice, and then liberalize its economy by dismantling the complex system of licenses, permits, and controls that had been suffocating economic growth.

The Indian state stepped back, allowing private companies and markets to flourish. India also abandoned the import substitution policy, embracing foreign trade instead.

Given his background as the ex-RBI governor, Dr. Rangarajan noted that the Indian banking system has performed well, partly due to the decision to allow private banks. He emphasized the importance of competition to ensure that public sector banks not only survive but also thrive.

On the question of how India can become a developed country, Dr. Rangarajan outlined a few key points:

1. He stated that India's per capita GDP needs to rise from the current level of about $2,500 to $13,000. To achieve this, the Indian economy needs to grow consistently at around 7%, and our investment rate as a percentage of GDP must increase to 35%—up from the current 33%.

He pointed out that the recent increase in the investment rate has been driven by government expenditure, which has also led to a rise in fiscal deficits. However, he stressed that government investment alone is not the answer. Instead, the government must create an environment that encourages the private sector to invest heavily and become the dominant source of investment.

2. On the broader topic of development, Dr. Rangarajan emphasized the need for a multi-dimensional strategy. He explained that the Asian Tiger economies—Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and South Korea—had adopted a one-dimensional growth model focused solely on export-led growth. But, he noted that this model is no longer viable in today’s world, as advanced economies are not growing as rapidly as they were in the 1960s. Moreover, these same advanced economies, including the U.S. and Europe, which had championed free trade for over half a century, are now ironically becoming more protectionist. This means an export-first strategy won't work for India.

3. Perhaps the most significant point he made, in our view, was about India’s monumental challenge with employment. He highlighted that employment in India isn't growing as fast as income. While "jobless growth" is a concern, he also warned that jobs without growth are not sustainable. He further added that new technologies will only exacerbate the problem and that government jobs are not the solution.

Dr. Rangarajan's insights offer a sobering yet insightful perspective on India's economic journey and the road ahead. These are crucial issues that we'll need to consider as we continue to chart our path towards becoming a developed nation.

Watch the full interview here:

Why is the the RBI governor worried about deposit growth

Look, it’s the job of the RBI governor to worry about things. As the head of the central bank, he’s got no shortage of things to stress over. This year, two issues have been keeping him up at night: the rise in unsecured loans and the widening gap between deposit growth and credit growth.

Now, we’ve talked about unsecured loans so many times that you might be tired of hearing about them, so we’re not going to dive into that again.

Instead, let’s focus on the second issue—the governor's concern about slowing deposit growth while credit growth stays high. He’s raised this concern multiple times, pointing out that banks are struggling to attract deposits because people are putting their money elsewhere:

1) At the FE Modern BFSI Summit 2024, he said, "Households and consumers who traditionally leaned on banks for parking or investing their savings are increasingly turning to the capital markets and other financial intermediaries."

2) At another event, he mentioned, "It goes without saying that there will always be some gap between the two, but credit growth should not run ahead of deposit growth by miles."

3) During the recent MPC meeting, he added, "It is observed that alternative investment avenues are becoming more attractive to retail customers, and banks are facing challenges on the funding front with bank deposits trailing loan growth."

Now, based on these comments, you might think that people are totally ignoring banks and are instead putting all their money into stocks, mutual funds, and other investments. But if you take a closer look, this narrative doesn’t quite hold up.

Soumya Kanti Ghosh, the Chief Economic Advisor at SBI, recently published an opinion piece that delves into this issue in detail. Let’s break it down:

He points out that, despite the RBI’s concerns, Indian banks have actually seen a huge growth in incremental deposits since the pandemic—around ₹61 lakh crores since FY22. Out of this, ₹59 lakh crores was lent out. But even with this significant growth, about a third of these deposits are tied up due to regulatory requirements, meaning banks can’t lend out all of this money.

Some of these deposits are lost in the system due to what he calls “leakages.” By leakages, he means deposits that banks can’t use for lending, like funds held by the government in its accounts.

In FY23, Indian households saved ₹29.7 lakh crores. Out of this, only ₹3.2 lakh crores went into mutual funds and other non-bank investments. Households invested ₹10 lakh crores in bank deposits and another ₹2.5 lakh crores in small savings. But Ghosh points out that this shift from bank deposits to mutual funds, etc., is just a change in the composition of assets—the money doesn’t actually leave the banking system. The seller who sold the shares or the money mutual funds used to buy shares ultimately stays within the financial system. So, this isn’t something to worry about. If anything, households moving away from FDs is actually good news for India.

But the most important point he makes is that 30% of that ₹61 lakh crores is counted towards statutory requirements of the RBI. This means banks can’t lend this cash out.

Finally, he notes that another form of leakage could be things like people paying TDS on bank deposit interest, income tax payments, etc.

He concludes by saying that it’s true that the nature of financial requirements and regulatory structures reduces the amount of deposits that can be lent out, but that’s just the nature of the financial system itself.

So, all of this isn’t as bad as the RBI governor might be making it out to be.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

If you have any feedback do let us know in the comments.

Very informative!!

Great work team zerodha !

These are really informative and help me a-lot considering I am planning to work in this field and pursuing CFA.

Keep up the good work.🫡