Hi folks, welcome to another episode of Who Said What? I’m your host, Krishna. For those of you who are new here, let me quickly set the context for what this show is about.

The idea is that we will pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualize things around them. Now, some of these names might not be familiar, but trust me, they’re influential people, and what they say matters a lot because of their experience and background.

So I’ll make sure to bring a mix—some names you’ll know, some you’ll discover—and hopefully, it’ll give you a wide and useful perspective.

For all the sources mentioned in this video, don’t forget to check out our newsletter; the link is in the description.

With that out of the way, let me get started.

Why India needs more solar than planned

I was going through Waaree Energies’ earnings call, and while a lot stood out, one remark from the CEO about India’s solar demand caught my eye.

Here’s what he said:

“I think the first thing that we need to understand and when we put all of these numbers in place, there is a DC capacity and then there is AC capacity and what we need to provide to go to the grid that has about anywhere between 1.3 to 1.4 times difference.

So, let’s say I need to add 40 gigawatts on the grid, it actually translates to around 60 to 65 gigawatts of solar panels. And then when you convert it into, let us say, capacity utilization of a typical plant that you have to add another factor of around somewhere around 15% to 20%. So then you are already hovering around, from a module perspective a demand translated into capacity terms around 70-75 odd gigawatts. That’s number one.

Number two, in the out years, if you consider 237 odd gigawatts of solar that we need to deploy by 2030 the demand is actually going up. And in the out years, you will see that it is actually going to go to 50, 60, maybe even higher in terms of gigawatts. And what is not factored in there is the potential rise, which will be caused because of two factors, one is data centers and the other one is green hydrogen. So, that is going to add to the demand further. So, if you look into the crystal ball, the demand is actually going to be much higher than what we see at this point in time. So, that’s the demand side.”

Now, if you haven’t tracked this space at all, this might look a little tricky to understand.

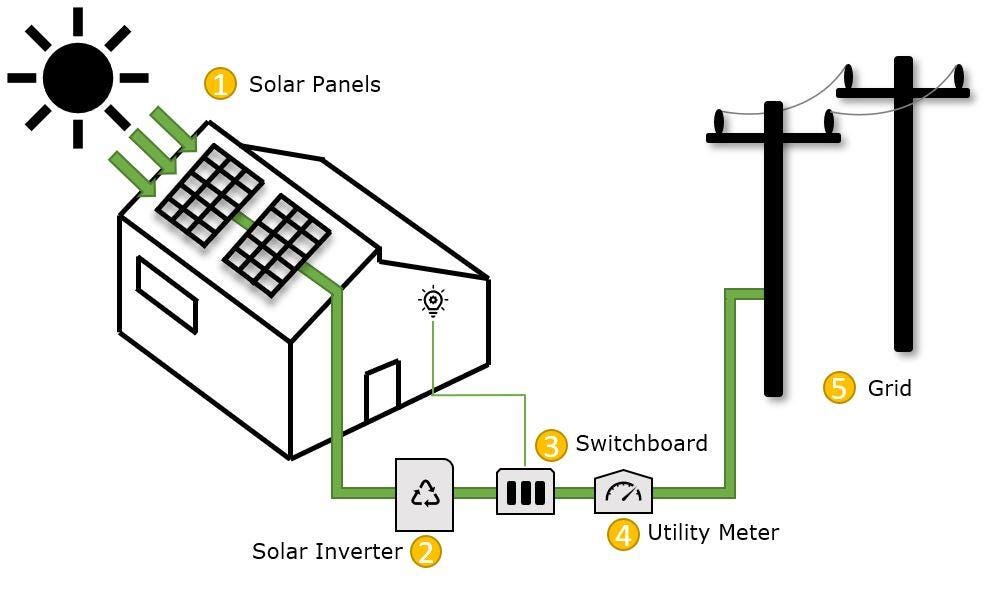

See, solar panels produce DC electricity, but our home and the electrical grid need AC electricity. So, between the solar panels on our roof and the grid, you need a device called an inverter. The inverter is the bottleneck that determines how much power can flow to the grid at any moment.

When the government says “40 GW of solar capacity,” it means 40 GW of AC power deliverable to the grid. But developers install more DC capacity — typically 1.3 to 1.4 times — to ensure that inverters are running closer to full capacity through the day.

That’s because sunlight is uneven. Solar plants produce nothing at night, ramp slowly in the morning, and hit their true peak for just a few hours around noon. Even then, panels rarely reach their rated output — heat, dust, and angle losses drag efficiency down. If you install 1,000 kW of panels for a 1,000 kW inverter, it might average only 600–700 kW through the day. But if you install 1,300 kW, you push the inverter closer to its limit for longer, lifting daily generation by roughly 30%.

Some power gets “clipped” during those peak hours, but the overall yield is much higher. Since solar can’t run 24/7, the logic is simple: when the sun is up, run flat out.

Then there’s manufacturing capacity. A factory rated for 10 GW a year rarely runs at 100%. Maintenance, retooling, ramp-up delays, and quality rejects mean 80–85% utilization at best. In India, even power availability can interrupt production. So to deliver 52–56 GW of modules, you need 65–70 GW of installed manufacturing capacity.

That’s the real math the CEO is walking through: a 40 GW grid target translates to 70–75 GW of module demand that is nearly double the headline number.

His second point is just as striking. India has about 127 GW installed today, targeting 280 GW by 2030 from solar energy. That’s an addition of 153 GW in five years, or roughly 30 GW a year on paper. But real build-outs don’t move in straight lines. The early years are slower: India added about 15 GW in 2023 and 22 GW in 2024. This means the later years must move faster to catch up. If you lag early, the tail end has to sprint: 35–40 GW a year, even 50 GW or more by the final stretch.

And that’s before accounting for the timing gap between orders and installations. Developers usually buy modules a year or more ahead of commissioning. So projects scheduled for 2028 will drive procurement spikes in 2027.

Put together, the government’s 280 GW goal doesn’t mean 280 GW of panels. It means India’s supply chain must be equipped to deliver almost twice that — because manufacturing, deployment, and procurement all peak well before the headline number does.

Btw, I came across all of these comments because we run a newsletter called The Chatter where we go through con-calls and management interviews. We then pull out the sharpest quotes from the management and curate them in a crisp newsletter.

PVR’s new plan to bring audiences back

You would have come across the news of PVR Inox trying out a dine-in cinema in Bengaluru, where you can literally eat a full restaurant meal while watching a movie.

I had mixed thoughts on this. So I wanted to see what the management had to say about it on their latest earnings call.

One of the analysts asked them something that’s actually a pretty fair question: “is this just a marketing play?” He said, malls already have plenty of good restaurants, and even inside your cinemas, there’s enough food already. So what’s new here?

And here’s what the management said:

“it’s a POC that we have worked around. As soon it basically gets its due success, then we scale it up across the country.

The objective out here is that you are watching a film alongside you have the gourmet food options coming across to you or being serviced to you.

This sort of a concept, a little similar to this was done by CJ Group out of South Korea, which was an extremely successful concept or which is an extremely successful concept. And this one is still much better than what CJ has done. We do believe that in the times to come, this is going to catch traction and then we shall be able to scale it up across other parts of the country also as well”

Ajay Bijli then added:

“ cinema is all about experience and having this circuit of close to 1,800 screens, we obviously have to be always innovative, experimental. 2004 is when we started our first gold class. It’s been over 10 years since Directors cut.

So every format has to evolve. It’s a pilot, but it’s already very successful. It is not a pivot for the company to get into -- compare ourselves to some F&B or QSRs that you mentioned. It is just that movies and food coming together has been our mainstay right from the beginning, and we’ll keep experimenting with formats.”

So it’s another premium format. But that answer got me thinking about why PVR is doing this now. Because the real story isn’t about serving gourmet food. It’s about survival.

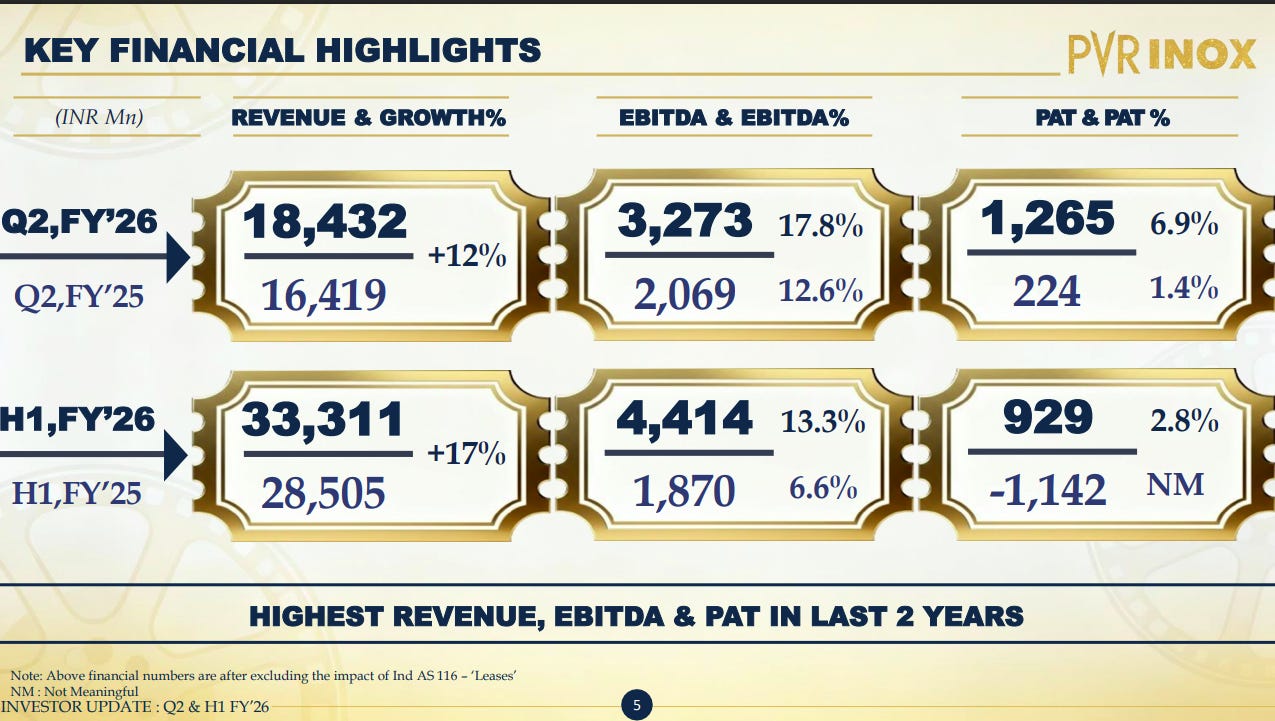

PVR Inox posted it highest PAT, i.e., ₹106 crore in the last 8 quarters. But that doesn’t mean the underlying business suddenly got easier.

Occupancy is still stuck below 30%, far from the 35% they used to hit before covid.

The economics of running theatres are still brutal. Rent, staff, maintenance — none of those costs fall just because people stop showing up. That’s why the pandemic hit the sector so hard. When seats stayed empty, the costs didn’t move. And when people finally came back, they didn’t return every weekend like before.

In the meantime, streaming became default. OTT platforms trained audiences to wait a few weeks for a digital release. On top of that, events, concerts, and stand-up shows exploded, giving people more options for how to spend their evenings. Going to the movies stopped being the default weekend plan.

That’s what’s pushed PVR to rethink its model altogether. It’s no longer just about building more screens — it’s about changing how those screens are owned and operated.

Over the past year, the company has moved towards co development and a FOCO model. Instead of spending ₹3.5–4 crore per screen from its own pocket, PVR partners with developers or franchisees who fund the property. PVR just operates the theatre, manages the brand and staff, and takes a share of the revenue as a management fee.

In simple terms: PVR wants to own the experience, not the real estate.

It’s a smart shift for a company that’s still trying to clean up a heavy balance sheet after years of expansion. But it doesn’t solve the main challenge: the fact that fewer people are watching movies in theatres at all.

But even as PVR experiments with formats, the bigger problem isn’t seats or food or pricing. It’s the supply of good films.

This quarter worked because there were hits — content people actually wanted to leave home for. But the industry’s fortunes still rise and fall with what’s playing on screen. If the films don’t pull people in, no amount of luxury dining or LED innovation can fill the halls.

That’s really the story here. PVR can change its model, cut its costs, and reinvent its experience — but it can’t control the one thing its business still depends on: whether there’s something worth watching.

That’s it for this edition. Thank you for reading. Do let us know your feedback in the comments.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

The newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.