Why Co-Working Spaces are Taking Over India’s Office Market

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

How Co-Working is Transforming Office Real Estate

HUL’s New Supply Chain Strategy

How Co-Working is Transforming Office Real Estate

We’ve been writing a lot about the banking sector over the past few days, and honestly, We were getting bored. So, we decided to switch gears and dive into something more exciting. Today, let’s talk about a sector in India that’s creating quite a buzz: the office real estate market—specifically, co-working spaces.

There’s a flurry of DRHPs (Draft Red Herring Prospectuses) popping up, with some highly anticipated listings from co-working companies. There’s even talk about WeWork India considering an IPO again. On top of that, major investors are pouring money into the flexible office space market, betting big on its potential.

If terms like “managed workspaces” and “hybrid models” sound confusing, don’t worry. We’ll break down the numbers, trends, and business models driving this co-working boom.

Let’s start with the big picture. India’s commercial real estate market—known as CRE—has been on a roll. In the top seven or eight cities—like Bengaluru, Mumbai, the National Capital Region, Chennai, and Hyderabad—there are about 650 to 700 million square feet of Grade A and Grade B office space available.

To give some context, “Grade A” offices are top-tier buildings with premium facilities and modern designs. “Grade B” offices, while decent, usually offer slightly lower-quality construction, fewer amenities, or less desirable locations.

That’s a massive number, and there’s even more on the way—about 45 to 60 million square feet are expected to be added in the next few years.

So, why all the excitement? India is a global hub for IT services, banking and finance, and a fast-growing startup scene. Companies are expanding, and foreign investors like Blackstone and Brookfield are pumping in a lot of money into commercial properties.

How big is this sector? Estimates suggest the total commercial real estate market is worth around $45–50 billion, growing at a steady 8–10% annually. That’s solid growth, especially given the ups and downs we’ve seen in recent years.

Now, let’s talk about co-working. Back in 2015, co-working was more of a niche idea. If you tossed a stone in Bangalore, you’d probably hit two startup founders. Startups and freelancers were working out of cozy cafés or small shared spaces. Fast forward to today, and co-working companies are taking over 6–7 million square feet of office space every year. By the first half of 2024, the total co-working footprint has grown to roughly 80 million square feet.

Here’s a fun fact to share at your next dinner party: co-working used to make up just 2–5% of India’s total office leasing. Now, in some quarters, it’s climbed to 12–15%. That’s a huge jump in just a few years! Big names like WeWork, Awfis, Cowrks, and 91springboard are growing rapidly, often opening multiple centers across several cities at once.

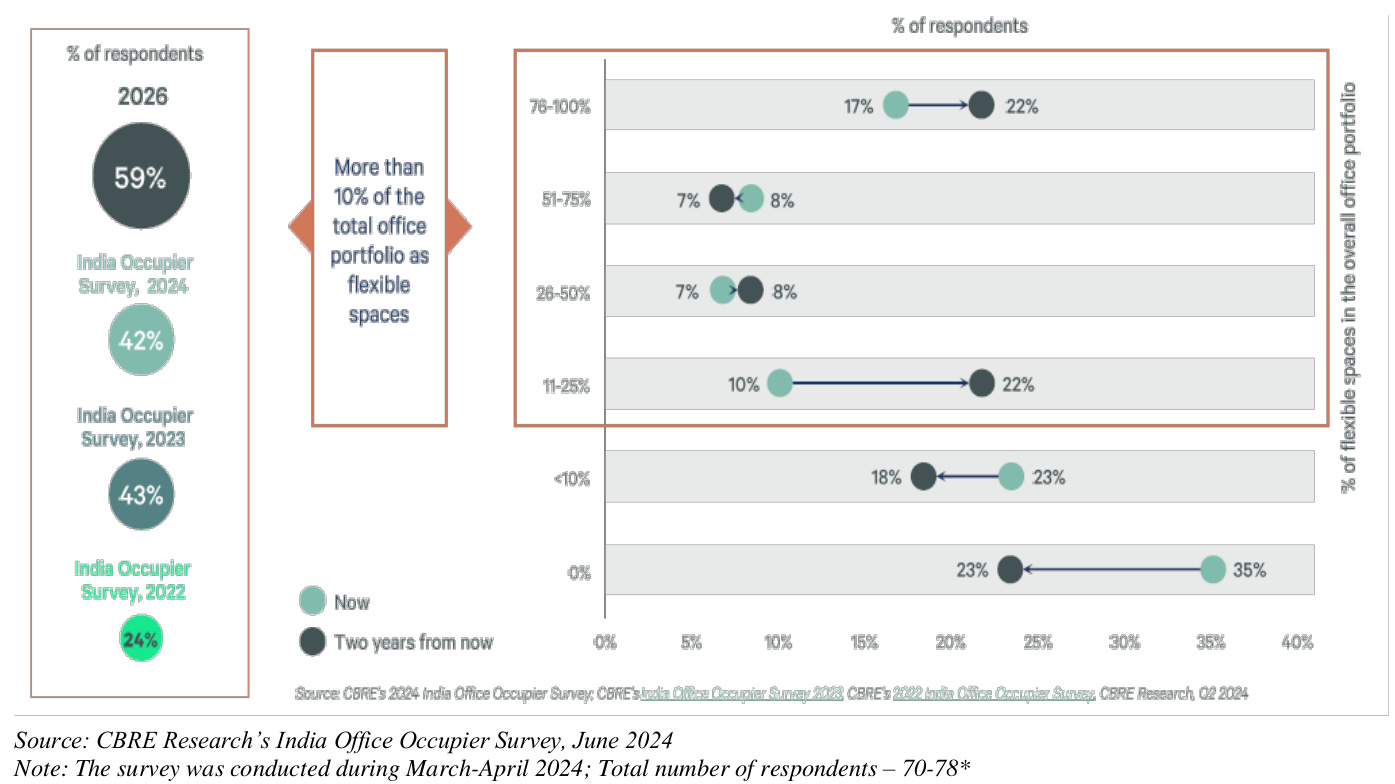

According to CBRE’s India Office Occupier Survey 2024, the number of companies with more than 10% of their office space in flexible setups is set to rise from 42% in early 2024 to 59% by 2026.

Why all the hype? It’s all about flexibility. Companies don’t want to commit to long-term leases anymore if they can avoid it. Instead, they prefer to pay for office space on a monthly or yearly basis and adjust the size as needed.

Hybrid work has also taken off since the pandemic. People want the option to work closer to home or drop into an office just a few days a week. For businesses, co-working means less upfront cost, less hassle, and an added benefit they can offer employees—especially Gen Z and Millennials, who really value flexible work setups.

So, what’s making co-working the trend to watch? Let’s break it down:

Startup Culture: India now has over 100 unicorns, and the startup ecosystem is booming. These companies need office spaces quickly, but they don’t want to lock themselves into 5–10-year leases. Co-working is the perfect solution.

Source: Smartworks Coworking’s DRHP Asset-Light Models for Big Corporates: Traditional corporates are jumping on board too. Many are adopting “hub and spoke” strategies, with a main office in the city center and smaller satellite offices in suburban or Tier-2 locations. Co-working spaces make this setup simple and cost-effective.

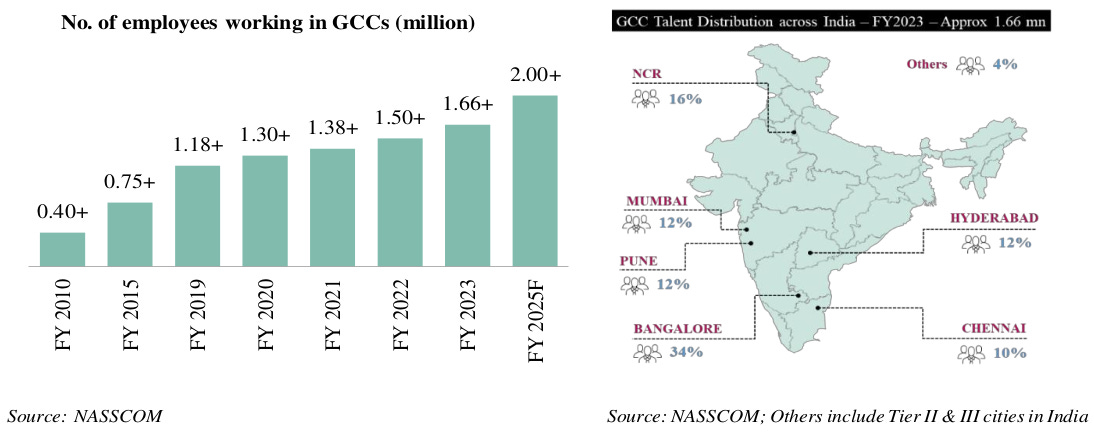

GCC Expansions: Global Captive Centers (multinational companies setting up tech or operations hubs in India) are also turning to co-working spaces. They need quick solutions without long-term commitments, and flexible office setups help them adapt to changing workforce needs.

Source: Smartworks Coworking’s DRHP Strong Investor Support: Big investors are backing co-working spaces because they see stable, long-term demand. With hybrid work on the rise, occupancy rates at some co-working centers are hitting 80–90%. Since 2018, real estate in India has attracted around $40.8 billion in FDI equity, with annual inflows averaging over $6 billion.

Source: Smartworks Coworking’s DRHP Redeveloped Spaces: Older commercial buildings are being revamped into modern co-working hubs. Landlords love this because smaller, flexible spaces are easier to rent out than a single large office.

Bottom Line? Co-working isn’t just for freelancers or small teams anymore. Large multinational companies are also signing up, bringing co-working into the mainstream in a big way.

Let’s talk about how co-working operators actually make money—or at least try to avoid losses. There are a few different ways they do this:

Straight Lease Model:

The operator signs a long-term lease for a property and outfits it with furniture, infrastructure, and everything needed to run a co-working space. They pay a fixed rent to the landlord and then charge clients monthly or yearly memberships.

It’s a high-risk model because the operator is stuck paying rent even if occupancy drops. But if they keep the space full, the rewards are big.

Major players like WeWork and CoWrks often use this model in prime locations since they’re better equipped to handle short-term setbacks.

Managed Aggregation / Revenue Share Model:

In this model, the operator and the landlord split the revenue. Sometimes the landlord even helps cover the cost of setting up the space.

The operator manages everything—bringing in tenants, running daily operations, and ensuring the space stays functional. It’s lower risk for the operator because they’re not tied to a fixed rent.

Margins might be slightly thinner than the straight lease model, but it’s a quick and scalable way to grow.

Franchise Model:

This works like fast-food franchising, but for office spaces. A co-working brand licenses its name, designs, and operating guidelines to a local investor or landlord.

The brand collects fees and possibly a royalty, while the franchisee takes care of most of the costs on the ground.

This model is great for expanding into Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities without needing heavy upfront investment.

On-Demand / Pay-Per-Use:

This is more of a pricing strategy than a business model, but it’s worth mentioning. Operators let people book space by the hour or day—perfect for freelancers or traveling professionals.

If they can maintain high usage rates, the returns are fantastic. However, since footfall can be unpredictable, it’s a bit of a gamble.

And there you have it—India’s office real estate market in a nutshell, with a spotlight on the booming co-working segment. We’ve looked at how big the market is, how co-working is growing rapidly, and the different ways these operators run their businesses.

To sum it up:

India’s commercial office space is huge, with over 650 million square feet and more being added every year.

Co-working has gone from a tiny share to 12–15% of leasing activity in some quarters—a massive leap.

Flexible offices are the future. Startups, big corporates, and everyone in between are getting on board.

Operators use various models—straight leases, revenue-sharing, and franchises—each designed to balance risk and growth in different ways.

HUL’s New Supply Chain Strategy

In our next story, let’s talk about a big change happening in India’s FMCG space.

Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL), India’s largest FMCG company, is rolling out a new way of delivering its products directly to retail shops. It’s called the direct-to-Kirana model, and it might soon replace the traditional system that companies like HUL have been using for decades.

Why does this matter to people like us? To understand, let’s first take a quick look at how an FMCG supply chain usually works.

Once a company like HUL—known for everyday products like soaps, shampoos, and detergents—makes its products, they need to reach small Kirana and retail stores.

For context, there are around 12 million Kirana stores across India, and HUL serves about 9 million of them.

Traditionally, HUL hasn’t dealt with these stores directly. Instead, they’ve relied on a network of distributors. These distributors play a key role—they buy products from HUL, store them, and deliver them to retail shops. They’re also responsible for collecting payments and passing on promotional offers to shopkeepers.

This system has worked reasonably well for years, even though it’s complex and expensive.

But times are changing. India’s retail landscape is evolving fast, and the way people shop has transformed. Over the past decade or so, online shopping has boomed. Today, e-commerce makes up about 17% of India’s FMCG sales. Within that, a rapidly growing segment—30–35%—comes from “quick commerce,” which wasn’t even around 3–4 years ago. Platforms like Swiggy Instamart and Blinkit now deliver groceries and essentials to your doorstep in minutes, making traditional shopping feel slow and outdated.

Even though online shopping accounts for just about 17% of FMCG sales, it’s already disrupting traditional supply chains in a big way. For companies like HUL, these digital platforms are taking over many tasks that distributors used to handle.

Today, online platforms can store products, deliver them to customers, and even manage discounts and promotions. With centralized warehouses and delivery networks, they’re much easier to work with compared to millions of scattered Kirana stores.

At the same time, Kirana stores themselves are becoming more tech-savvy. Many now use digital tools like point-of-sale systems and ordering apps to run their businesses more efficiently. This means they can bypass distributors and deal directly with manufacturers like HUL.

To keep up with these changes, HUL is starting to take more control of its supply chain than ever before. Instead of relying on distributors to handle logistics, HUL is gradually taking over the entire process—stocking, picking orders, transporting goods, and ensuring that products reach retail stores directly.

To make this happen, they’re expanding their centralized warehouses and building delivery networks designed for this new approach.

Of course, HUL isn’t diving into this blindly. They’ve been developing digital tools like an app called Shikhar to make the transition smoother. For context, this app is already used by over 1.3 million retailers. It allows shopkeepers to place orders directly with HUL and provides HUL with valuable insights into demand patterns, inventory levels, and even store-specific preferences. This kind of data would have been much harder to gather in a system that relied heavily on distributors.

There’s also a financial reason behind this shift. Distributors typically earn a margin of 3–10% on the products they handle. For a company like HUL, with an annual turnover of about ₹60,000 crore, this adds up to a significant amount. By cutting out or reducing the role of distributors, HUL can save costs and redirect those savings elsewhere—whether to lower prices for customers or to improve profit margins.

That said, there’s a small financial challenge HUL will need to address.

Here’s how it works: distributors usually get a credit-free period of around 15–16 days from companies like HUL. This means they receive products and only pay for them 15–16 days later. Distributors then pass on a credit-free period of 30–45 days to retailers. The difference—about 15–30 days—is essentially a service distributors offer to retailers.

Now, if HUL removes distributors from the equation, they’ll have to take on this credit responsibility themselves. This could increase their costs, at least in the short term.

Let’s talk about costs for a moment. The FMCG sector has been under pressure recently due to rising food inflation in India. Prices of essential raw materials like wheat, sugar, and milk have gone up, squeezing profit margins. By streamlining its supply chain, HUL hopes to offset some of these costs and avoid passing them on to consumers.

But not everyone is on board with this change. Distributors, understandably, aren’t happy about being sidelined. The All India Consumer Products Distributors’ Federation (AICPDF) has raised concerns, calling the direct-to-Kirana model misleading and out of touch with ground realities. They’ve even warned of nationwide protests if distributors are negatively impacted by this shift.

So, what does all this mean for people like us?

On one hand, HUL’s move shows how a company can adapt to a rapidly changing market by using technology to stay ahead. On the other hand, it highlights the tensions that arise when innovation disrupts traditional systems.

For now, all eyes are on how this transition plays out and whether it truly delivers the benefits HUL is aiming for.

Tidbits:

New Year’s Eve 2024 saw a massive surge in orders on quick-commerce and food-delivery apps. Blinkit surpassed last year’s entire NYE order volume by 5 PM, with its biggest single order coming in at ₹64,988 from Kolkata. Zepto reported a 200% growth in orders compared to last year, including 3,345 orders for ice cubes per hour. Swiggy Instamart doubled its NYE 2023 sales, with a record order of ₹70,325 from Goa. magicpin processed up to 1,500 orders per minute, with its largest order touching ₹30,000. Cities like Bengaluru, Chennai, and Mumbai led the way, showing how much people now rely on instant delivery for celebrations.

TANGEDCO recently canceled a ₹2,100 crore tender to install 8.2 million smart meters, rejecting Adani Energy Solutions Ltd.’s winning bid over high costs. This decision comes amidst allegations of irregularities linked to the Adani Group. Retendering the project may delay much-needed upgrades meant to reduce power losses and improve billing efficiency, signaling stricter scrutiny of public-sector contracts.

In November 2024, India’s petroleum exports dropped to $3.72 billion—nearly half of the $7.39 billion recorded the previous year. Between April and November, exports fell by almost 19% due to weak global demand, issues caused by the Red Sea crisis, a sharp drop in Russian crude imports, and rising domestic consumption. The Suez Canal blockade forced shipments to take longer routes, increasing costs. On top of that, competition from new refineries like Nigeria’s Dangote further reduced India’s share in key markets, underlining the challenges of shifting energy trade dynamics.

-This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Anurag

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉 Join the discussion on today’s edition here.

Dude I think you pasted the wrong pic 😭

What's mudasir and salman doing in the article😂