Why are so many malls in India so empty?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India’s ghost malls need a revival

How commercial vehicles fared this quarter

India’s ghost malls need a revival

Many of us would have walked into a mall that looks like this.

From the outside, it looks a little dead, as if the building hasn’t been painted for years. A couple of signboards are broken, and the entrance lights are dim. Inside, the air-conditioning might be working, but the corridors are eerily empty. A few establishments might be open: a salon here, a restaurant there, maybe even a co-working space. But no one seems to be getting their hair cut, or eating, or working there. There is no real “mall” feeling. You find yourself wondering how the place is even surviving.

That, in the language of real estate, is a ghost mall. And this is not a problem that’s unique to India. China, for instance, also had a massive ghost-mall problem. So did the US.

The real estate consultancy Knight Frank has been tracking this problem for a few years now. In its latest edition of the “Think India Think Retail” report, the firm argues that these dying malls are not just an eyesore, but also a huge pool of underused capital and land. Instead of treating them as failures, the report tries to measure how big this ghost stock is, where it sits, and what it would take to bring at least some of it back from the dead.

This story isn’t entirely about ghost malls, though. It reveals some interesting insights about how it is that Indians like to shop.

With that in mind, let’s dive into the findings of their report.

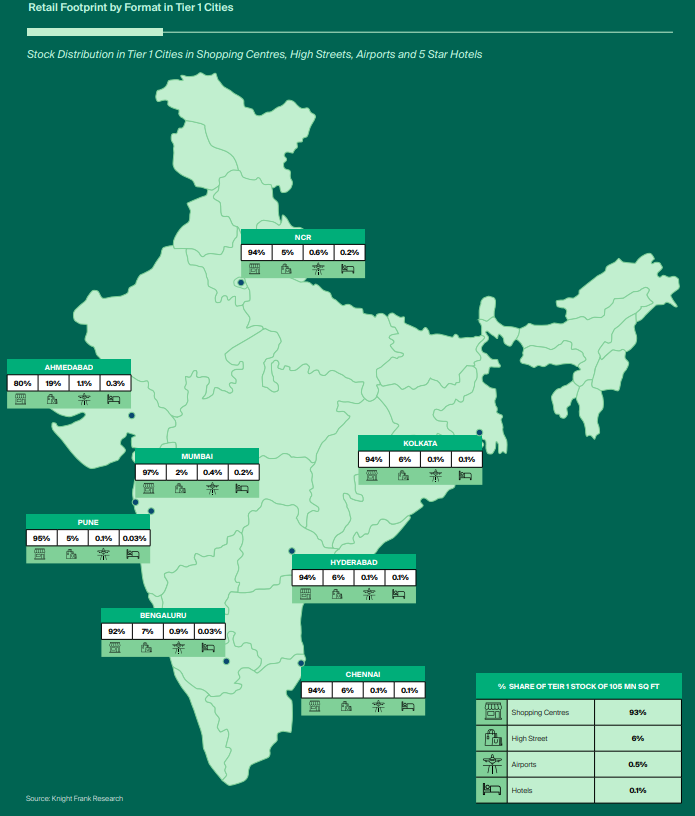

Where India shops

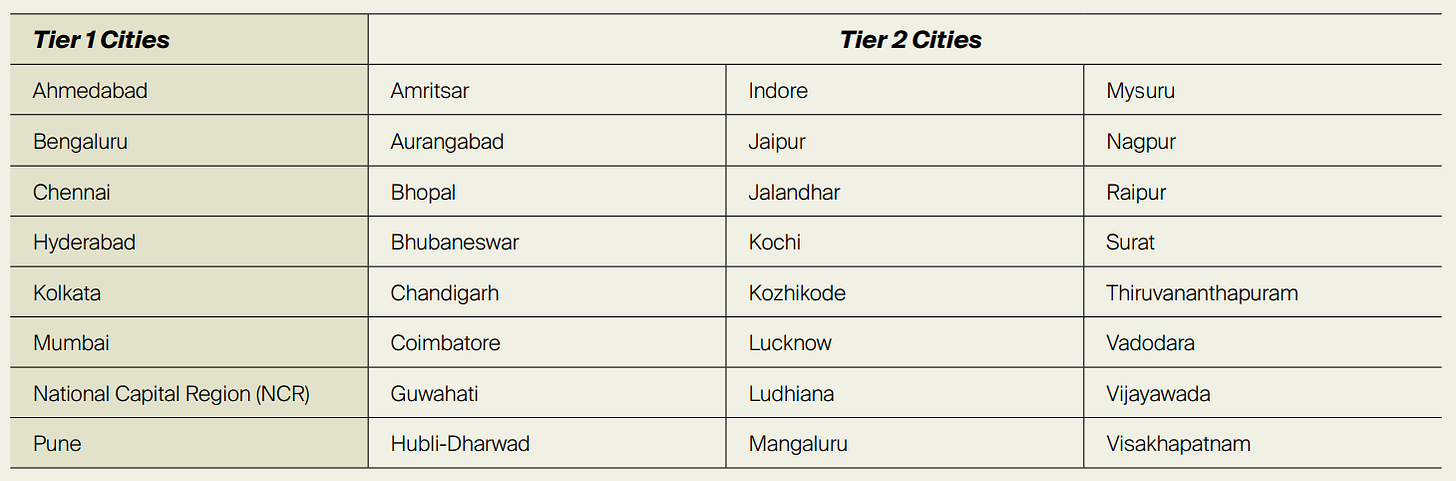

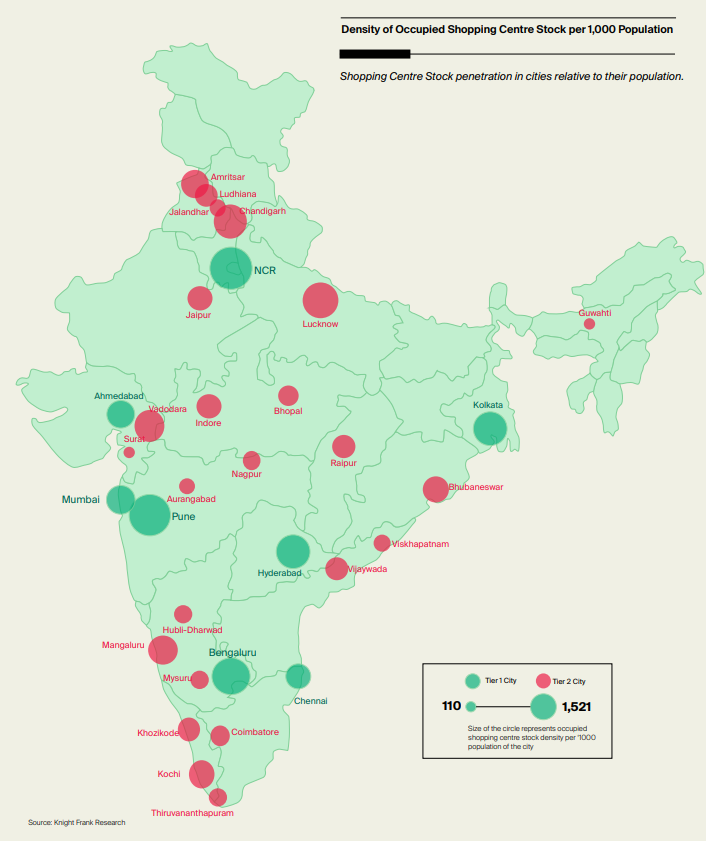

Knight Frank looks at where India actually shops and builds a full map of it. They pick 32 cities and count every big piece of organised retail in them. They found 365 working malls with over 22,400 stores. But this map also includes 58 high streets.

What’s a high street? Well, think of an area like MG Road in Bangalore, or Park Street in Kolkata, or even CP in Delhi. In itself, they’re not really a mall, but they’re legacy shopping streets where most of the city collides. Combined, these streets house 7,900 outlets.

Then, there are also shops in 17 airports, as well ~340 stores inside 302 five-star and heritage hotels. All of this, in sum, is the entire universe of organized physical retail in India.

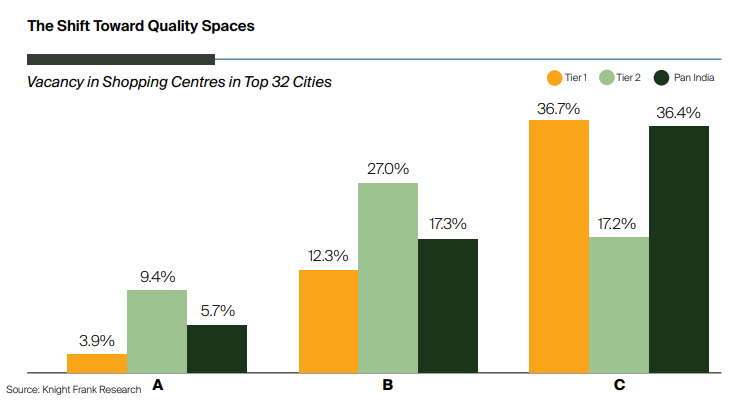

Knight Frank then runs this entire universe of malls through a simple filtering process. They first sort malls by overall quality — things like how well they’re built, who the retailers are, how well they’re run, and whether the ownership is clean and centralised. After that, they tag any mall that is old enough and mostly empty as a “ghost mall”.

Once they’ve identified these ghosts, they look at them again to see which ones are actually fixable. They look for whether the mall is in a good area, whether the neighbourhood has spending power, and whether the building itself can realistically be turned around.

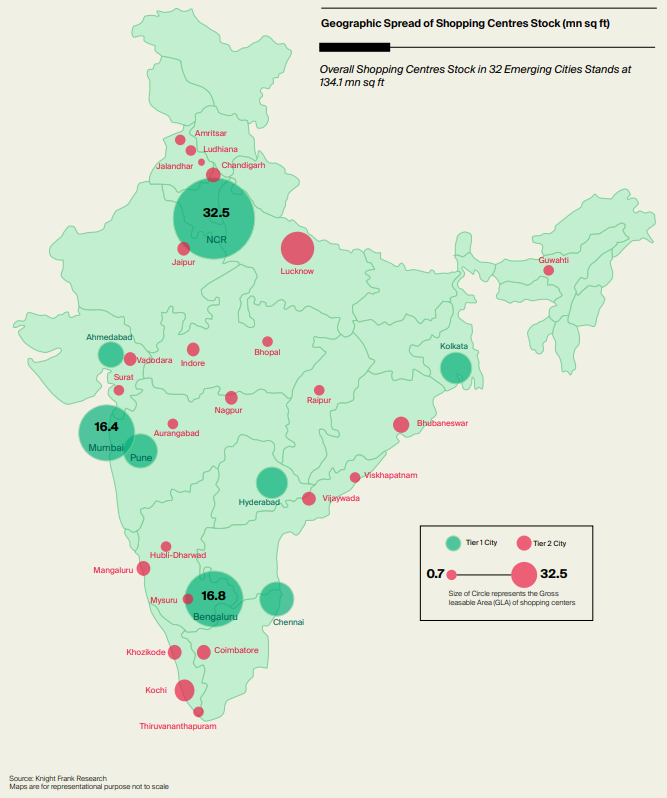

At the broadest level, the report is saying something most people who live in Indian cities already know instinctively. It’s that malls carry most of the weight when it comes to organised retail, but they’re hardly the only places where shopping actually happens.

In the big metros, Knight Frank counts about 105 million square feet of formal retail space, and almost all of it — 98 million square feet — sits inside malls. The rest is scattered across the big high streets, airports and five-star hotels.

What this essentially means is that malls may dominate the built footprint, but the way people actually use a city remains far more mixed. A mall is where you go when you want a controlled environment — air-conditioning, parking, a cinema, a predictable set of brands under one roof.

But the high streets still handle a part of everyday life. They’re where you stop to pick up something small, or where you drift after college or work.

Why some cities lean on malls and others don’t

Some places have embraced malls deeply; others have barely dipped a toe in. Cities like Mangalore and Lucknow, for instance, have very high “occupied mall space per person”, which means that malls there are part of daily consumption. People go not just for big-ticket shopping but for everyday purchases simply because malls offer the cleanest, safest public space available.

Then, there are cities at the extreme opposite end. Surat and Ludhiana are large, wealthy, and commercially active cities — yet their malls barely register on a per-capita basis. That’s not because people don’t spend. It’s because these cities already have strong high-street traditions: like textile corridors in Surat, or market clusters in Ludhiana. So, even though the numbers say there isn’t much mall space, that’s not reflective of the true volume of retail activity there. Instead, demand flows through older, more established channels.

The metros fall somewhere in the middle of this spectrum. Delhi-NCR, Mumbai, Bengaluru and Chennai have lots of mall stock simply because of their size. But once you divide that by population, they don’t look extraordinarily mall-heavy.

What they are, however, is deeply polarised. A handful of top-notch centres in metros are always full — like Delhi’s Select Citywalks, Bangalore’s Orion Malls, and so on. But a long tail of older or poorly planned centres sits half-empty.

Why do ghost malls exist?

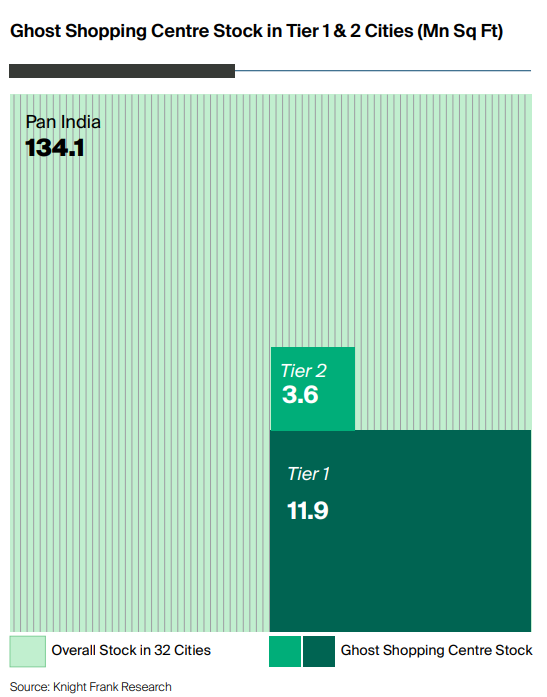

Knight Frank defines ghost malls very simply: any shopping centre that’s at least three years old and has 40% or more of its space sitting empty.

By this definition, India has roughly 15.5 million square feet of ghost mall space today. Most of it is in the big metros rather than smaller towns. Notoriously, the satellite cities that compriCan these places be saved?se Delhi-NCR — like Gurgaon, Noida and Ghaziabad — have lots of ghost malls.

These are the kinds of malls many people have seen at some point: places that were lively a decade ago but slowly lost their big stores, their cinema, or their supermarket. And once those “anchor” tenants left, the smaller shops followed suit. What’s left is usually a building that still calls itself a mall but doesn’t function like one anymore.

The reasons for why they exist are surprisingly mundane.

Some malls were built in the wrong place, far from real catchments. Some malls were built in ways that just didn’t work for people. The walking paths didn’t flow naturally, so you’d end up in corners where nothing was happening, or corridors that felt a little dark or forgotten. The design of the mall mattered.

Who the tenants were might also have mattered. In many older centres, for instance, every shop was sold off to different small owners, which meant no single person could decide which brands should come in or how the overall mix should look. Instead of feeling like one unified mall, the place behaved like hundreds of separate shops with no shared plan — and that makes it almost impossible to build a coherent experience that attracts people.

In many cases, competition killed them. A new mall opened nearby with better design, stronger anchors, maybe a more compelling F&B offering, and the old one never recovered. Retail is emotionally driven: once consumers stop treating a mall as “the place to go”, that mental shift is hard to reverse.

Another potential reason is just plain old overcapacity — that we built way too much in excess of real demand. At least partly, this dynamic is confirmed in the case of China, which is anyway going through a massive real estate bubble. Whether India is going through a real estate bubble is up for heated debate, but it’s worth considering.

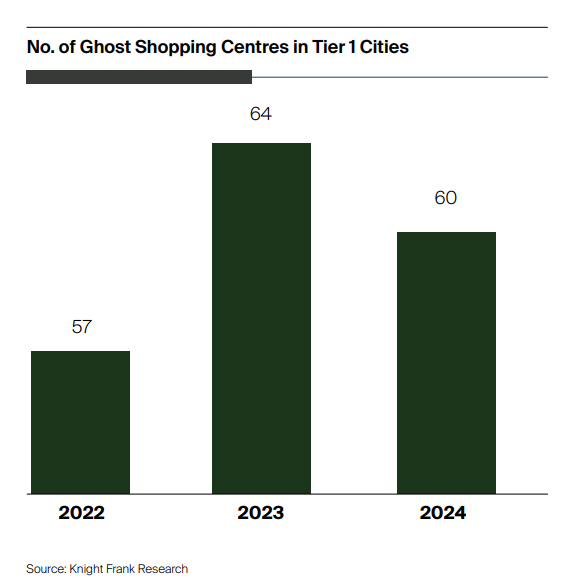

Knight Frank’s report shows that the ghost mall trend is not slowing down. Tier-1 cities had 57 ghost malls in 2022, 64 in 2023, and 60 in 2024.

The slight improvement between 2023-24 is because a few of them have been actively revived or repurposed. For instance, Central Mall in Bangalore was repositioned with Westside and Zudio, while parts of older Mumbai malls were converted into offices or educational hubs. But the larger point remains: for every mall that flourishes, a few more slip into irrelevance.

A good mall with 5-6% empty space still feels alive. A mall with 40% empty space, though, feels unnerving. And once that mood sets in, it reinforces itself. No tenant wants to be the only open shop on a dead corridor. No parent would take their child to a dimly-lit mall because it could be unsafe — even if it really isn’t.

Can these places be saved?

However, there might be a silver lining. These spaces, Knight Frank argues, can be salvaged. And this is key to solving the ghost mall problem at least partially.

Out of the 15.5 million square feet of ghost mall space, ~4.8 million square feet — which is 15 malls in 11 cities — is actually worth reviving. These are not hopeless cases. They’re malls in good catchments that simply fell behind or were mismanaged. If they’re refurbished and repositioned, the report estimates they could together generate around ₹357 crore of annual rental income. The West and South of India dominate this opportunity, and the big metros alone account for two-thirds of the potential value.

When you step back, the whole thing is pretty straightforward. India built a lot of malls over the last 15–20 years. Some worked, some didn’t. The ones that didn’t aren’t mysterious failures. The Knight Frank report is basically saying: don’t write these places off. A lot of them can be fixed, and the ones that can’t still sit on good land that can be used for something better. Cities change, people change, and buildings have to keep up.

Ghost malls are just the leftovers from an earlier phase of urban growth. The real question now is what we do with them — whether we let them decay or whether we turn them into something useful again.

How commercial vehicles fared this quarter

If you’ve driven late at night on long roads or highways, you must have seen huge trucks that are probably carrying something massive. Probably, it could be cement to construction sites, or a shipment of Amazon packages to another location, and so on.

These trucks, and the buses and the buses that ferry you across cities, get classified as Commercial Vehicles (CVs). Their role in the economy is abstracted away from us, but that doesn’t reduce their importance. This segment of vehicles matters because when India’s factories produce more, commercial vehicle sales rise. When construction projects pick up, tipper sales climb. When e-commerce booms, LCV demand surges.

In short, they drive the backbone of how logistics work across India.

Now, within CVs, each vehicle type is classified based on Gross Vehicle Weight (GVW). This refers to the maximum total weight a vehicle can carry, including its own weight, passengers, and cargo. On that note, the sector is broadly divided into the following categories:

Heavy Commercial Vehicles (HCV) — these are the trucks that have a GVW above 16,000 kg. Likely, they carry the massive rigs that haul steel, containers, and bulk commodities across highways.

Medium Commercial Vehicles (MCV) — these have a GVW between 7,500-16,000 kg. They are mostly used for carrying items from a warehouse to various smaller end retail stores.

Light Commercial Vehicles (LCV) — these vehicles have a GVW range between 3,500-7,500 kg. and form the backbone of last-mile delivery in cities.

Small Commercial Vehicles (SCV) are sub-3,500 kg mini-trucks and pickups, often the first vehicle for a small entrepreneur.

The last category is buses that serve public transport needs.

We’ll be looking into the latest quarterly results of the two biggest companies in this space: Tata Motors and Ashok Leyland. Both drove a strong rebound after a subdued first quarter. Each of them has enjoyed similar tailwinds, while also playing nuanced strategies.

Let’s dive in.

Tata Motors

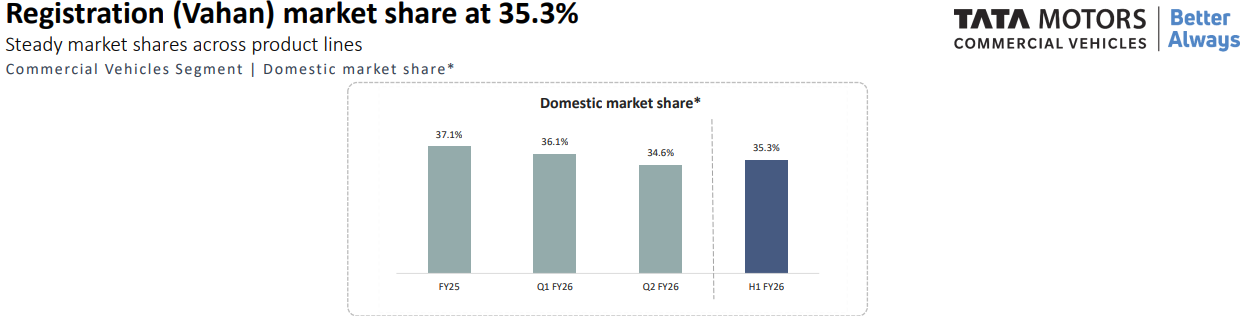

Tata Motors has dominated the CV market for decades. While in recent years, competitors have chipped away at its lead, it remains the industry leader with a ~35% market share. Recently, Tata Motors demerged its passenger vehicles (PVs) and its CV business — which is now listed separately as Tata Motors Commercial Vehicles (TMCV).

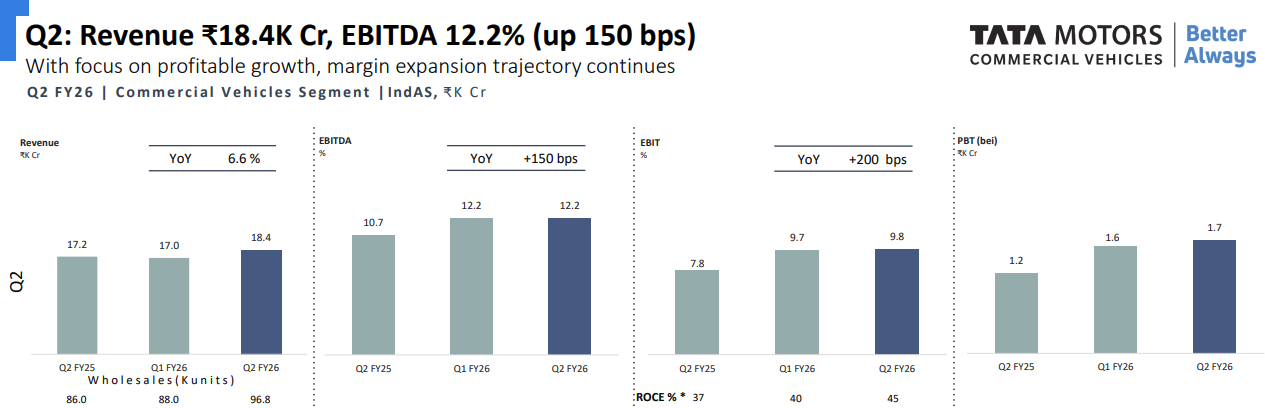

This quarter, TMCV posted revenue of ₹18,370 crore — a 6.6% increase from last year. The EBITDA margins came in at 12.2% — an improvement of 1.5 percentage points from last year. CV companies typically operate in the 10-14% EBITDA margin range during healthy periods.

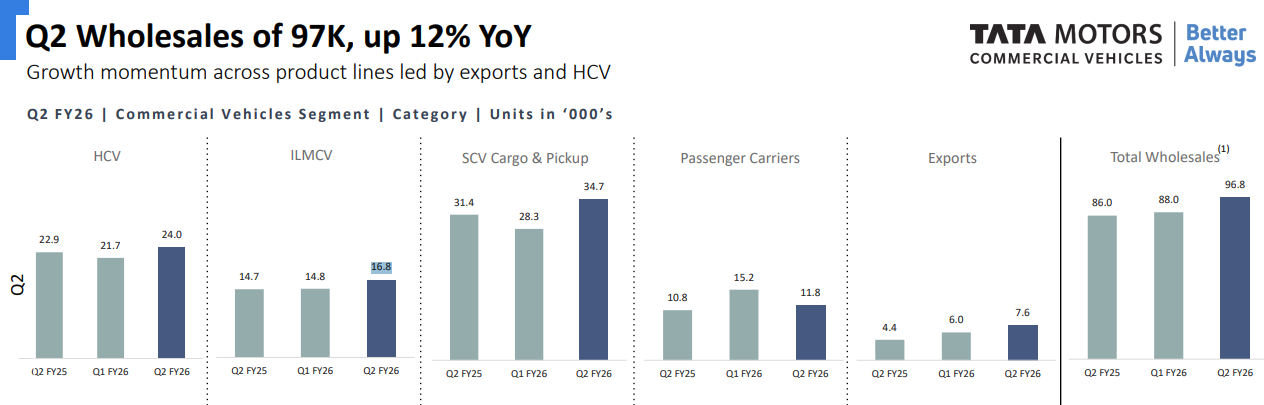

Volume contributed most significantly to this margin improvement. Wholesale volumes sold to dealerships hit 96,800 units, up 12% annually. This was faster than their revenue growth — perhaps, this could mean that the realizations per vehicle were slightly lower.

The GST cut

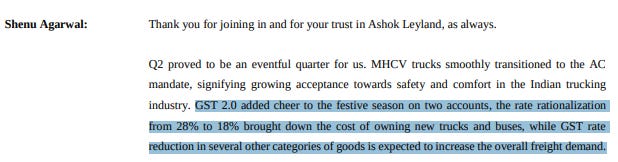

One reason why these realizations could have been lower is because of the GST cut on CVs, which was passed on to customers. Now, GST on CVs has been lowered from 28% to 18%, and this cut worked on two levels. First, the direct benefit went to small fleet owners and individual buyers who don’t claim input tax credit — they simply paid 10% less for their vehicles. Additionally, the GST cut on spare vehicle parts and tyres also reduced running costs, improving the total cost of ownership (or TCO) of a CV by 1-1.5%.

But there was a second-order effect, too. GST cuts across multiple product categories meant more goods being produced and consumed. This meant more freight moving around the country, which pushed up truck utilisation.

However, where GST was a tailwind for them, some sectors were not — the tipper trucks used in construction and mining had a rough Q2. The reason is simple: these sites shut down or slowed significantly due to heavy monsoons. By October, utilisation had already bounced back above last year’s levels.

How India moves freight

An interesting section in TMCV’s earnings call was on the dynamics of how India moves freight.

See, India is building something called Dedicated Freight Corridors (DFCs), which are high-speed railway lines meant purely to move goods. They’re supposed to be an antidote to India’s conventional rail lines which are already very clogged. Right now, just the Western and Eastern DFCs are fully operational.

Now, the question is: could the existence of these DFCs cannibalize the truck business of TMCV? The answer is largely no. The management gives region-specific examples as to why that is. In the Eastern DFC, for instance, many of the goods moved are commodities, which were earlier moved on older trains — so there’s hardly any loss there.

In the Western DFC, however, the impact is a little more nuanced. A lot of the goods moved include import-export containers, which are generally moved by lorries (which TMCV makes). This might slow down the growth of lorry sales. However, the DFC runs only between major hubs, and not the points each hub is expected to serve. What TMCV hopes is that, as the DFC increases movement of goods, there will be a greater need for certain CVs to provide point-to-point delivery of those goods.

If anything, net-net, in TMCV’s view, the rise of DFC may end up benefiting their business.

The EV play

Meanwhile, TMCV is taking its EV play seriously.

Last quarter, TMCV launched the Ace Pro EV, which is primarily meant for last-mile delivery as well as FMCG distribution and waste management. And it has caught some good traction early on — since the launch, 1,300 units have already been delivered. TMCV has also built out the supporting charging infrastructure, with ~25,000 public chargers across 150 cities for its small commercial vehicles.

Its EV play isn’t just for trucks or tempos — it extends to buses, too. TMCV signed an agreement to supply 100 Magna EV intercity coaches to a South Indian intercity travel brand called Universal Bus Services. Tata has delivered all electric buses from previously won tenders and is now participating in the PM E-Drive tender through a consortium model.

Ashok Leyland

Ashok Leyland is the second-largest player in India’s M&HCV segment, occupying a 31% market share in those segments. But, unlike the common perception of being purely a heavy truck and bus specialist, LCVs already constitute 35% of its product mix, and take up a ~13% share of the LCV market.

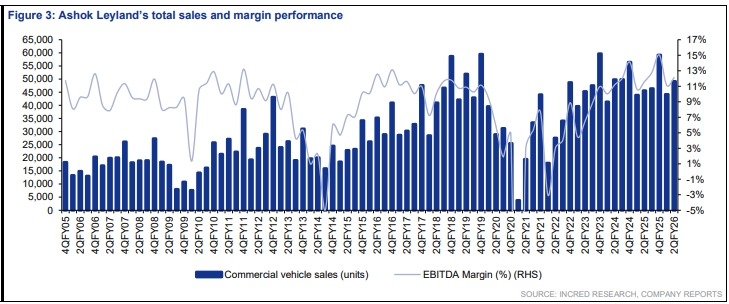

Ashok Leyland’s standalone revenue came in at ₹9,588 crore in Q2 FY26, up 9.3% year-on-year. The EBITDA margins grew by 0.5 percentage points annually to 12.1%. They dispatched 49,116 units, which was ~8% more than the same time last year.

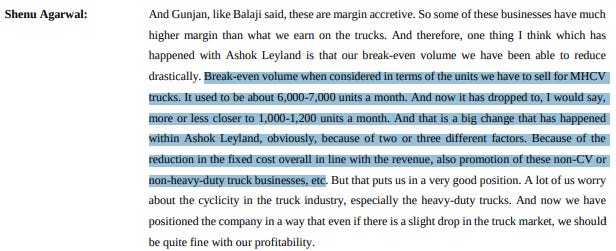

Most strikingly, Ashok Leyland has become much more operationally efficient. Compared to 6,000-7,000 units monthly a few years ago, it now just takes them 1,000-1,200 units a month to break even. This improvement is driven by a meaningful reduction in fixed costs across the organisation, and a growing contribution from higher-margin, non-truck businesses — such as defence, power solutions, and LCVs.

Much like Tata, Ashok Leyland passed on the GST benefit to customers similar to Tata Motors. The effects, of course, were largely the same. It was also similarly hit by dampening construction activity due to heavy rains — since then, its truck utilization has stabilized.

But it’s the EV play where things get more differentiated.

Electric dreams

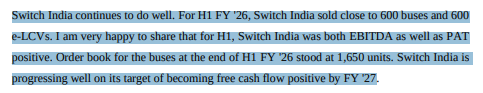

Now, Ashok Leyland makes its EVs under a brand called Switch India, and so far, it has had a very strong year. The brand delivered close to 600 electric buses and 600 e-LCVs in the first half of the year alone. Impressively, the business, while still fairly small, has already achieved a positive PAT in that period. They have a strong order book that stood at 1,650 buses by the end of H1 FY26, and the company targets free cash flow positivity by FY27.

Now, Ashok Leyland has another subsidiary called OHM Global Mobility. But they don’t manufacture anything of their own. Instead, they procure the vehicles made by Switch, and then operate and maintain them as a fleet. Then, institutions (like corporates) contract OHM’s fleet services, who usually charge them on a subscription or pay-per-use basis, and promise to take end-to-end care of the fleet. The most common customers, though, are public bus operators, who are instead charged on a per-kilometer basis.

OHM has over 1,100 such electric buses, with an impressive fleet availability of more than 98%. It added 250 buses in Q2, and is targeting 2,500+ buses over the next 12 months. They find this a lucrative business — partly due to the aid of government policy — and continue to invest more resources in it.

But Ashok Leyland’s EV play goes beyond the front-facing vehicles. In fact, it has now ventured into making its own batteries, instead of buying them from outside suppliers. We’ve covered before how India depends significantly on China for battery technology. By manufacturing batteries in-house, Ashok Leyland gains two huge advantages: it can control costs better, and it doesn’t have to depend on external suppliers who might face shortages for what is probably the most important component of an EV.

Conclusion

Both Tata Motors and Ashok Leyland had a strong quarter. Partially, this is buoyed by the GST cut. But the other part of it is genuine operational improvements in the business. The monsoon has thankfully not played enough of a spoilsport role.

But it’s how they’re both approaching EVs in their own way that’s interesting. Ashok Leyland’s Switch turned EBITDA and PAT profitable, and OHM is running over 1,100 electric buses. Ashok Leyland is also moving to manufacture batteries in-house—a bet on controlling costs and supply as the EV transition picks up.

Both companies are using this moment to build out their EV portfolios and tighten their cost structures. The next few quarters will show whether these bets pay off.

Tidbits

SBI to hire 16,000 annually; add 200–300 branches in FY26

SBI will recruit ~16,000 people every year and open 200–300 new branches in FY26 as it works to double its business to ₹200 lakh crore in 6–7 years. It will also deploy 6,000 “ATM mitras” via its OSS subsidiary to monitor and maintain 60,000 ATMs, with a sharper push in rural and semi-urban markets.

Source: BusinessLine

TCS to buy Coastal Cloud for $700 million

TCS has signed a $700 million all-cash deal to acquire U.S.-based Coastal Cloud, a top Salesforce Summit partner with 400+ certified specialists. The deal strengthens TCS’s AI-led Salesforce consulting, expanding capabilities across marketing, service, revenue and data cloud—making TCS one of the top 5 global Salesforce partners.

Source: Business Standard

QCO exemption hurting stainless steel capex: Jindal Stainless MD

Jindal Stainless says the government’s continued QCO exemption on stainless steel imports is delaying industry capex and weakening sentiment. Low-quality imports from China and Vietnam are rising, squeezing margins and hurting MSME manufacturers. The firm is still pursuing anti-dumping relief and advancing its ₹40,000 crore Maharashtra plant and Odisha chrome mine projects.

Source: Business Standard

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Vignesh.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Great article....