Who will win the quick commerce wars?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts and video on YouTube.

Is quick commerce a bubble?

Remember the early days after the pandemic when quick commerce companies like Grofers—now Blinkit—and Zepto were just starting to gain traction? Back then, it felt like everyone was joking that this was just another way for VCs to burn through cash, right?

Well, fast forward to now, and against all odds, quick commerce companies are actually doing pretty well. Venture capitalists are all over it. Just last week, I saw two big headlines:

First, Zepto is reportedly on the verge of securing a $340 million investment. That’s a lot of millions. And then there’s Ola, which is apparently jumping into the quick commerce game too. Seriously, is there anything Ola isn’t trying to get into?

Whether we like it or not, we can’t deny that we’re hooked on the convenience of getting everything from onions to air coolers delivered in just 7 minutes. A lot of people have cut back on their grocery store runs and are instead turning to Blinkit and Zepto.

But if you think about it, how can a business that delivers Snickers in 7 minutes possibly make sense, let alone be sustainable?

So, I dug into the economics of quick commerce to make sense of it all. Here’s a quick overview.

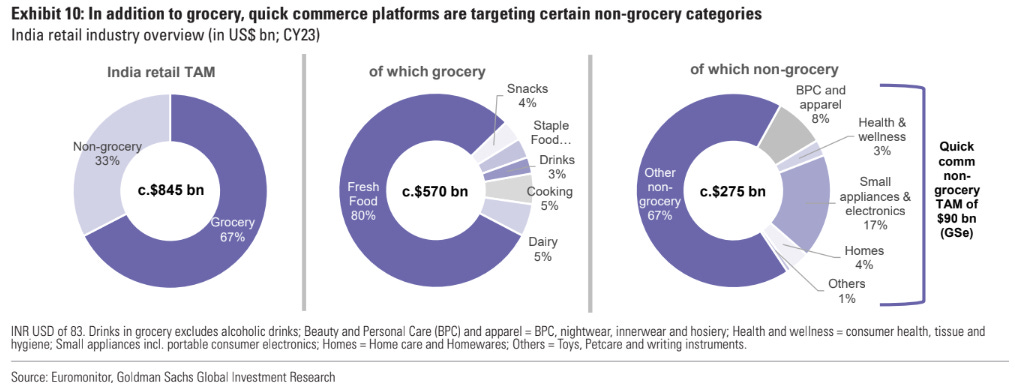

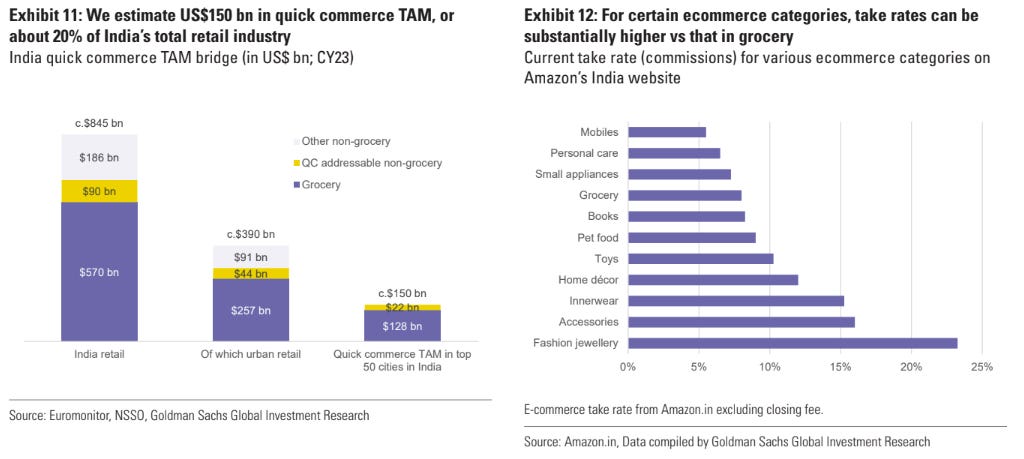

Let’s start with the total addressable market, or TAM, which is what gets VCs excited about any new venture. According to Goldman Sachs, the overall retail TAM is worth a whopping $845 billion. Of that, they estimate quick commerce could take up as much as 20% of the pie—around $150 billion. That’s a serious chunk of change, especially considering that a decade ago, quick commerce didn’t even exist.

Now, in terms of the players, Zomato’s Blinkit, according to a report by JM Financial, has a market share of over 40% by Gross Merchandise Value. Just a few years back, Swiggy’s Instamart was one of the top contenders, but it’s lost some steam lately.

A survey by The Ken, a business news site, showed that Instamart isn’t even the second choice for users anymore. Zepto seems to be eating into Instamart’s market share despite being the younger company. That might explain why Zepto has been able to secure back-to-back funding rounds. Their last valuation was a staggering $3.6 billion.

We don’t have a lot of numbers on Zepto or Instamart since they’re private, but Blinkit’s figures are out there because Zomato is publicly listed.

Here’s how quick commerce works:

At the heart of these super-fast deliveries are hundreds of “dark stores” and thousands of delivery partners. A dark store is essentially a micro-warehouse located close to high-demand areas, like densely populated neighborhoods. The goal is to be as close as possible to customers for the quickest deliveries. Blinkit, for instance, has around 639 dark stores and plans to expand to 2,000 by 2026.

These dark stores usually operate on a franchise model, costing around ₹90 lakhs to set up, with franchisees earning a 3-5% commission. On an average weekday, a typical dark store processes about 1,500-1,700 orders, and that number jumps to 2,000-2,500 on weekends.

According to JM Financial, the cost per order for a dark store averages around ₹22 if it’s handling about 1,400 orders per day.

But here’s the kicker: last-mile delivery, the final leg from the dark store to your door, is the biggest expense for these platforms. Companies like Zepto and Blinkit use a mix of electric and petrol motorbikes, as well as bicycles. Bicycles are usually used for short deliveries (under 1.5 km), while motorbikes cover longer distances.

It’s estimated that delivery partners earn a net amount of ₹3,800-4,100 per week.

The average order value (AOV) for Blinkit has seen a significant rise recently. In the last quarter, the AOV hit ₹625, and the gross order value (GOV)—which is the total revenue from all orders before costs—exceeded ₹4,900 crores, up by 130% year-over-year.

But the big question is: can these platforms continue to grow at this pace, or is this just a bubble waiting to burst? And more importantly, will they ever become profitable?

Management at these companies seems optimistic. They’re experimenting with different ways to boost their take rate, like gradually increasing platform fees. There’s also ad revenue, which is picking up nicely. But the reality is, we’ve yet to see a profitable quick commerce model anywhere in the world. Will India be the exception? I guess we’ll have to wait and see.

As Deepak Shenoy, CEO of CapitalMind, said in a conversation with The Ken, “The problem with this narrative of quick commerce is that, in the end, when you go public, you’re going to have to deliver on these narratives. If the narrative is strong, you’re going to get valuations.”

Your electricity bill might go up

The Supreme Court just handed down a game-changing judgment that’s going to make life a lot tougher for metals and mining companies. In this recent ruling, the Court gave state governments the green light to levy a mining cess on land where minerals are mined. And get this: states can even go back as far as April 1, 2005, to collect these taxes. The only tiny bit of relief is that states can’t charge any late fees or penalties on taxes that were due before July 25, 2024.

But don’t worry, companies won’t have to pay it all at once. The back taxes will be spread out over 12 years, starting in April 2026. So, there’s at least some breathing room.

Now, this ruling settles a long-running debate about whether states have the right to pile on extra taxes on top of the regular royalties mining companies already pay. The Supreme Court says yes, they do. The reasoning? It’s important for states to earn revenue from their natural resources to fund local government projects, like building infrastructure and providing services.

This is huge for the mining industry, and here’s how it’s shaking out:

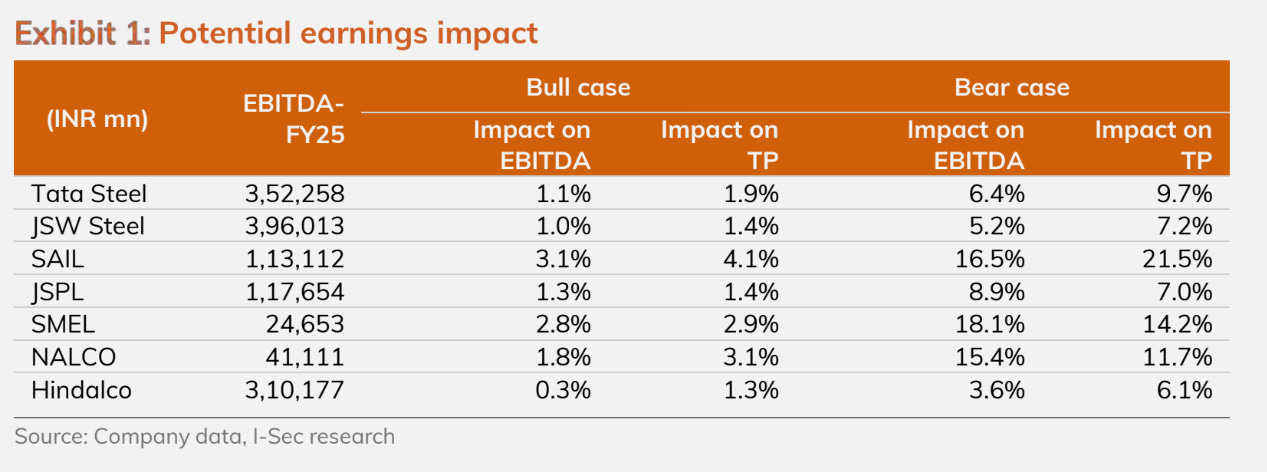

Tata Steel has already set aside a whopping ₹17,300 crores to cover these potential tax demands, mainly from the state of Odisha. That’s a massive chunk of change that could limit Tata Steel’s ability to invest in new projects or pay dividends.

SAIL (Steel Authority of India) is staring down potential tax bills of around ₹3,000 crores.

JSW Steel has liabilities of ₹4,700 crores, but they’ve already paid ₹900 crores of that.

These provisions are going to be a significant ongoing cost for these companies and could really limit their financial flexibility over the next decade.

On the flip side, companies that mine limestone, which is used to make cement, seem to be in slightly better shape. The taxes on limestone are lower than those on coal or iron ore, so companies like UltraTech won’t feel as much of a pinch. Sure, their costs will go up a bit, but they’ll likely pass those costs on to customers. For most cement companies, the extra tax might only nibble away about 5% of their profits from FY24, according to Nomura’s estimate.

Looking ahead, this new tax could make the cost of doing business in mining much more unpredictable. Different states might set different tax rates, so the cost of minerals could vary widely depending on where they’re mined. This kind of unpredictability could spook new investors—nobody wants to suddenly face higher taxes that could eat into their profits.

There’s also an indirect effect to consider: your electricity bill. Since a lot of India’s electricity comes from coal, companies like Coal India are going to face higher costs due to these new taxes. There’s a good chance those costs will get passed down the line. That means power plants might end up paying more for coal, and eventually, those higher costs could show up in your electricity bill.

How much your bill goes up will depend on how state regulators handle these increased costs. In some states where electricity prices are tightly controlled, the impact might be less noticeable at first. But in markets where power prices aren’t as regulated, you could see prices climb pretty quickly.

But here’s the bigger question: is retrospective taxation a good idea? India is working hard to attract global investments, but these backward-looking tax demands could scare investors away. If businesses aren’t assured of a stable and predictable investment environment, why would they take the risk?

Chinese troubles are getting worse

So, the next story is about China. And we know what you’re thinking: “Why are these guys always talking about China? Is this a Chinese podcast or something?”

But here’s the thing—China is the world’s second-largest economy, and whatever happens there ripples across the globe. And ever since COVID hit, it feels like there’s always something weird or crazy going on in China. And right now, that “something crazy” is definitely happening.

But before we dive into that, let’s talk about the bigger picture—the context in which all this craziness is happening.

The Chinese economy is facing some serious problems:

First off, for decades, China relied on an investment-led growth model. They pumped trillions into building massive amounts of infrastructure—think ghost cities, endless highways, and bridges that lead to nowhere. This strategy worked for a while, helping China grow at a blistering 8–9% annually, turning it into the world’s second-largest economy.

Second, China became the factory for the world by focusing on exports. This was possible because of China’s high savings rate, but the flip side was that consumption was always a relatively small part of the GDP.

Third, while this growth model works wonders initially, there’s a limit to how long you can keep spending to fuel growth. Once the low-hanging fruit is picked, every additional dollar you invest yields diminishing returns.

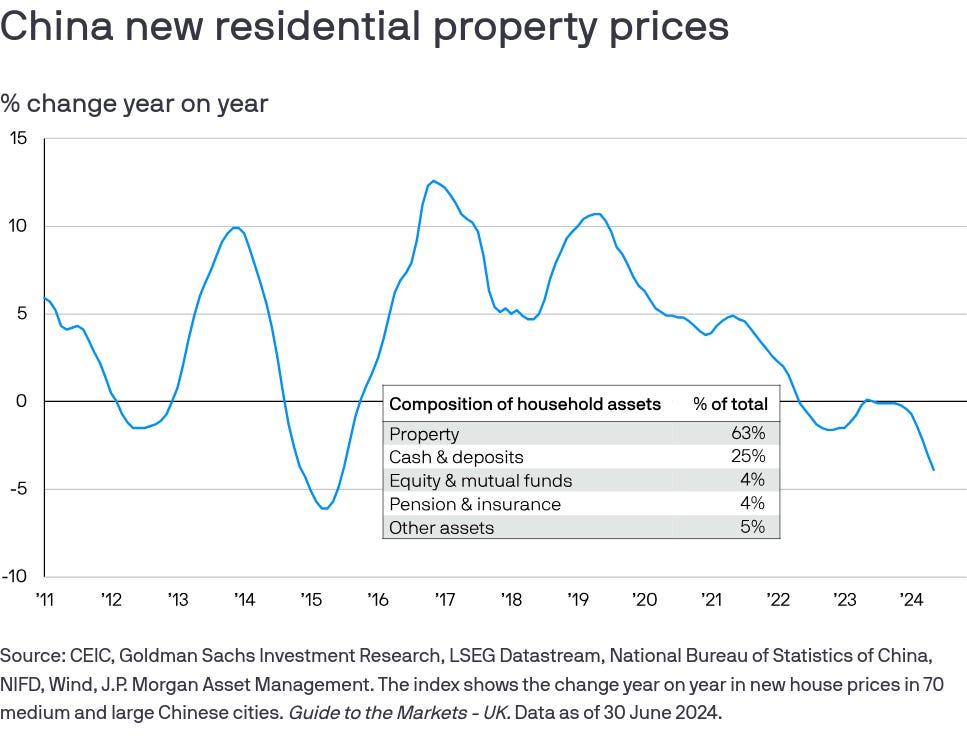

China also has a debt problem, but it’s more at the local government level. For years, local governments funded themselves through property sales, thanks to the booming real estate sector. But that boom is over. China started cracking down on the property sector in 2021, and since then, property prices have been on a steady decline for over three years.

And on top of all this, China is facing a demographic challenge with an aging population. This leads to lower productivity and a shrinking workforce.

Now, all these issues that have been brewing for decades are bubbling up to the surface. The thing with structural problems like these is that you might not notice them when your economy is growing at 8%. But when growth slows down, as it has since COVID, these problems become impossible to ignore.

Back in 2021, the Chinese government introduced regulations to curb leverage and speculation in the real estate sector, which had a dramatic impact on property prices. And it’s been downhill ever since. Prices have been falling with no bottom in sight.

Here’s the kicker: property is the biggest household asset in China. Most Chinese people don’t invest in stocks or mutual funds; they invest in houses and land.

This has triggered a series of knock-on effects. With property prices falling, many people decided to use their savings to pay off mortgages instead of spending more. The same goes for credit card debt. And those who were saving became super conservative, putting all their money into bank fixed deposits.

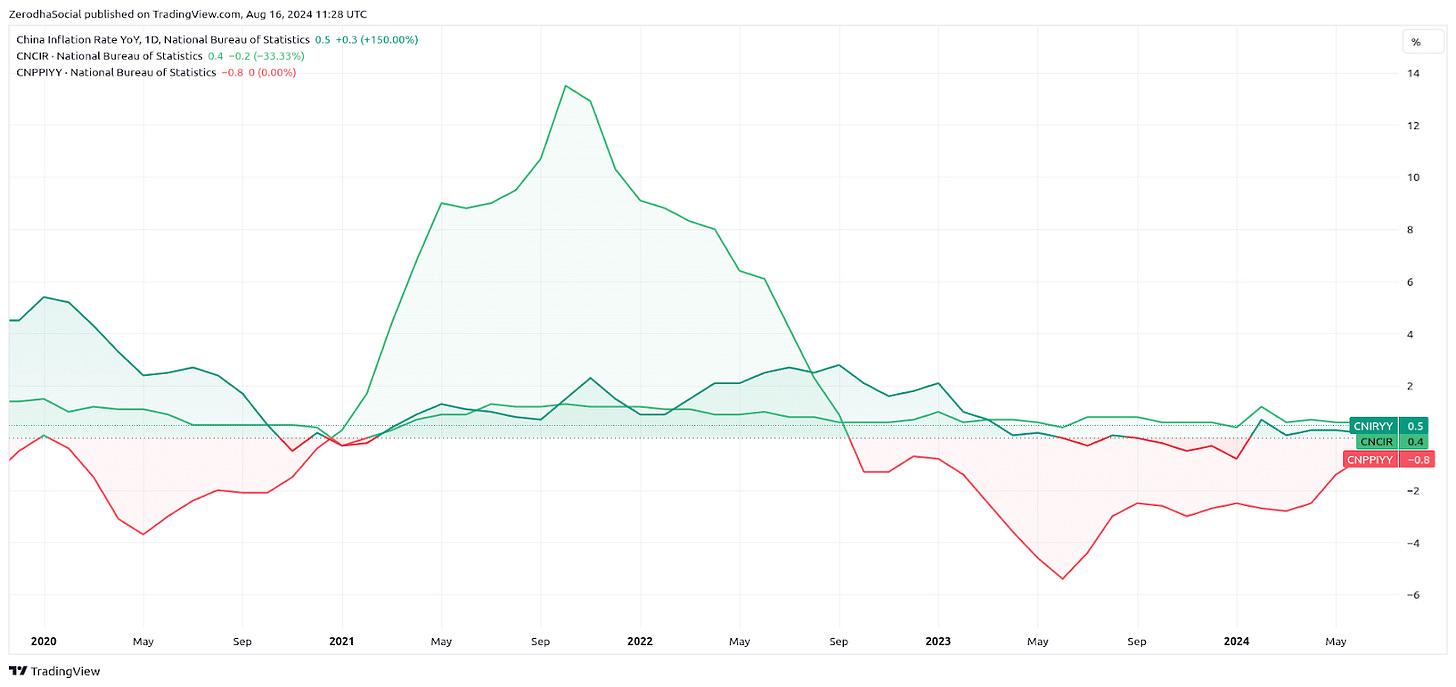

The result? Ultra-low inflation. While the rest of the world was grappling with inflation, China was experiencing the opposite. In fact, in 2023, China even dipped into deflation for a brief period.

So, why are we telling you all this?

As we mentioned earlier, property was the go-to investment for Chinese households, but with prices plummeting since 2019, people have had to look for other options. Since most households don’t invest in equities, the alternatives were fixed deposits or government bonds. And guess what? Both domestic and foreign investors have been piling into government bonds.

So, why the rush into bonds?

First, given the terrible shape of the Chinese economy, bonds have become the go-to investment for domestic institutional investors and regular folks alike.

Second, because China’s economic issues aren’t going to be solved anytime soon, foreign investors are snapping up Chinese bonds, betting on interest rate cuts.

Third, falling inflation naturally leads to lower bond yields, which attracts even more investment into bonds. Remember, as yields fall, bond prices rise, so people are eyeing those capital gains.

Source: WSJ

But now, the Chinese government and regulators are getting worried. They’re saying there’s a bubble in Chinese bonds, and they’re going to some pretty extreme lengths to prop up bond yields.

Regulators are doing everything from warning banks against buying government bonds to imposing fines, scaring banks with investigations, and even canceling some bond purchases.

So, what’s going on?

The Chinese government claims it’s worried about a Silicon Valley Bank-style run, where rising interest rates could lead to massive unrealized losses on bonds held by banks. But this seems like a remote possibility since China is dealing with deflation, not inflation.

They’re also concerned that the yield curve might flatten. If short- and long-term bond yields are the same, banks could see their profitability hurt because they wouldn’t be able to make long-term loans at higher interest rates than short-term loans. But honestly, this worry seems a bit overblown too.

It’s a weird situation for China to be in, but for observers like us, it’s actually becoming quite entertaining to watch.

Thank you for reading, if you have any feedback, do let us know in the comments.

Thank you for sharing information notbonlynof india but globally As I am 58 years I feel I have to learn more and keep myself updated by what happening around me.Just waiting for Monday to get a dose from you about the happening around us.

Please select a time to post daily this way it could become a habit for us to read