Who said what on India's economy, Zomato’s real value, drilling for oil & investing strategies?

Hey everyone, welcome to another episode of Who Said What! This is the show where we take interesting comments, headlines, and quotes that caught our attention and dig into the stories behind them You know how every week, there’s a bunch of headlines that grab everyone’s attention, and there’s so much hype around them? Well, in all that chaos, the nuance—the real story—often gets lost. So that’s the idea: to break things down.

Economic survey says bold things about India

The Economic Survey is out. For those who don’t know, it’s the government’s report card on the economy. It doesn’t just look back at how the economy performed—it looks forward. The Chief Economic Advisor (CEA), V. Anantha Nageswaran, uses this document to highlight what's going right, what’s going wrong, and what needs fixing. It’s one of the most important documents for anyone who wants to understand where India is headed.

So, Bhuvan, who’s the boss of Markets was through this year’s Survey and something struck him—right there in the first ten pages. The CEA wrote this:

"One of the refrains in the Draghi report is the ‘China Challenge’ to European competitiveness. It is no less for India. Several commentators have recently written about the manufacturing colossus that China has become in the last six years."

Our CEA compares India to Europe—and not just any Europe—a crisis-ridden Europe where productivity is flatlining, innovation is lagging, and industries are struggling to compete.

It’s rare for India, still an emerging economy, to be compared with a developed region like Europe on such serious economic challenges. That too in the first few pages of the survey itself. That's a point of concern. The CEA is telling us that India could be heading down the same path unless we wake up.

So, what’s this Draghi report all about, and why does it matter to us?

Think of Mario Draghi as Europe’s “fixer.” Do you know Winston Wolf from Pulp Fiction?

He’s the guy you call when things have gone south and you need someone to clean up the mess. That’s Draghi for Europe. He’s the former President of the European Central Bank and the man who saved the euro during the debt crisis. Now, Draghi had written this report that lays out exactly why Europe is struggling and how it can claw its way back to competitiveness.

His diagnosis is brutal: Europe is at risk of long-term economic stagnation. Productivity is stuck, innovation is weak, and industries are overregulated and underinvested. Does this sound familiar? It should. Many of the issues Draghi highlights—productivity bottlenecks, dependence on foreign tech, and weak investment—are directly relevant to India.

Draghi's new plan for the European Union calls for massive yearly spending of €800 billion to strengthen Europe—that's 7 lakh and twenty-two thousand crore in Indian currency. He wants to make business rules the same across all EU countries and reduce Europe's dependence on other nations for critical supplies and technology. Let’s break down the key areas he identifies, and I’ll explain how these problems mirror India’s own challenges.

1. Productivity Stagnation and Market Fragmentation

Draghi opens with a warning: Europe’s productivity is flatlining. In the 1990s, Europe’s productivity growth almost caught up to the US. But since then, it’s stalled. The reasons? Europe failed to ride the tech boom that fueled US growth, and its internal markets are too fragmented. Different countries have different regulations, creating what Draghi calls “hidden tariffs.” These barriers stifle businesses, especially in services, preventing them from scaling across the EU.

India faces a similar problem, even though it’s at an earlier stage of development. Reforms like GST were meant to unify the market, but businesses still face state-by-state regulatory hurdles. For example, logistics companies have to navigate a maze of state-level permits and compliance requirements. Infrastructure projects often get stuck due to inconsistent land laws across states.

2. The Innovation Deficit

In the global innovation race, Europe is falling behind. The US and China are pulling ahead in critical technologies like AI, semiconductors, and clean energy. Europe’s problem is twofold: low R&D investment and a risk-averse financial system. Startups in Europe struggle to raise venture capital and rely too heavily on bank loans, which aren’t suited for risky, high-growth innovation.

India has its own version of this issue. While Indian tech startups have made headlines, long-term R&D spending is still less than 1% of GDP. Sectors like electronics manufacturing and EV technology remain dependent on imports. And while India’s VC ecosystem has grown, growth-stage funding for deep-tech innovation is still limited.

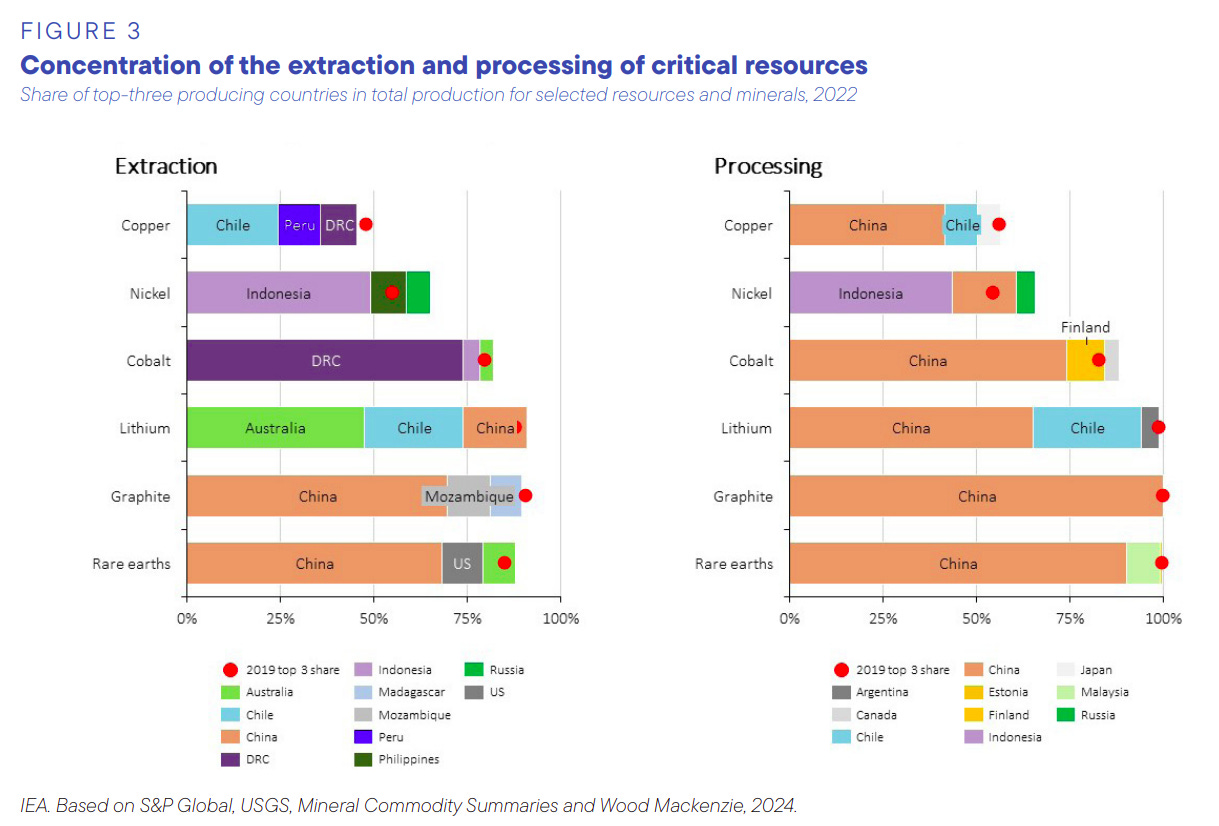

3. The China Challenge

Draghi points out that Europe is dangerously dependent on China for critical raw materials, especially those needed for renewable energy. China dominates the global supply chain for solar panels, batteries, and rare earth elements. This puts Europe at risk of supply chain disruptions and price shocks.

India faces the exact same challenge. As we push for clean energy, we’re still importing the bulk of our solar components from China. Supply chain issues during the pandemic exposed how vulnerable India’s renewable energy projects are to external shocks.

4. Ease of Doing Business

Draghi emphasizes that Europe’s complex regulatory framework is stifling business growth. Different countries have different rules, making compliance a nightmare. Draghi argues that bureaucratic inertia is one of Europe’s biggest obstacles to competitiveness.

India’s experience is strikingly similar. While we’ve improved in the Ease of Doing Business rankings, red tape is still a major headache for entrepreneurs. Small businesses face multiple layers of compliance that slow down operations and discourage investment.

Draghi’s recommendation is simple: governments need to “get out of the way.” The CEA also spoke about deregulation in the economic survey saying:

“Lowering the cost of business through deregulation will make a significant contribution to accelerating economic growth and employment amidst unprecedented global challenges”

5. Defense Spending and Economic Security

Defense may not seem like an economic issue at first, but Draghi argues that it’s critical to long-term security and competitiveness. Europe’s defense budgets have been constrained by fiscal pressures, leaving it reliant on US military support through NATO.

India’s defense challenge is different but equally pressing. We face a dual-front threat from China and Pakistan, yet much of our defense spending goes toward personnel costs rather than modernization. Without investments in advanced defense technology, we risk falling behind in a critical area.

6. Public and Private Investment: Unlocking Growth

Europe has underinvested in infrastructure and technology for years. Draghi proposes a massive €800 billion annual investment plan to drive growth. However, he warns that this requires both public funding and private sector confidence.

India faces a similar challenge with infrastructure financing. While programs like Bharatmala have increased public investment, many projects are delayed due to funding gaps and bureaucratic hurdles. India needs to strengthen public-private partnerships and attract more long-term foreign capital.

These are some of the major points from Draghi’s report. What’s clear is that India has no doubt come a long way. But there’s still a long way to go.

The fact that the CEA highlighted Draghi’s report within the first 10 pages of the Economic Survey should not be taken lightly. It’s a reminder that the same cracks appearing in Europe’s economy could threaten ours if we don’t act quickly. Draghi’s message is clear: competitiveness isn’t guaranteed—it’s earned.

The question is—how will India respond?

Is Zomato a 1rs stock?

There’s always a lot of talk about which stocks are hot in the market, and Zomato often pops up in those conversations. Recently, Anurag Singh, MD of Ansid Capital, made some strong comments about it in an interview with NDTV Profit.

He said Zomato is a “one-rupee stock” that’s already “300x from ₹1.” He’s saying that early investors—especially private equity—made huge returns, and now retail investors are left with a stock that’s priced way too high.

So, is Zomato really overvalued? Well, maybe yes. Its price-to-earnings (PE) ratio is somewhere around 300, which is extremely high. If you see this graph, the stock is down close to 30% from its peak.

But is it actually a one-rupee stock? That feels like a bit of an exaggeration to me. The thing with growth companies like Zomato is that they aren’t valued based on how much money they’re making right now. People bet on what the business could become in the future. Some might say narrative defines the value of the stock. Sometimes that story can get ahead of reality, and that’s exactly what Anurag is questioning here.

This is something I understood from the dean of valuation—Aswath Damodaran. He had valued Zomato at ₹41 per share when it IPOed in 2021. At the time, he wasn’t convinced that the Indian food delivery market could grow fast enough to justify the hype. In an interview with Livemint, he said:

“When you pay 10 times revenues for a Paytm or a Zomato, you are making judgments about what the total market will be and what their market share will be, but you're not explicit about it.”

However, Damodaran later said he was willing to revisit his stance. He acknowledged that businesses evolve, sometimes in unexpected ways. Zomato’s acquisition of Blinkit—which many, including Singh, criticized—may not have been such a misstep after all. Blinkit gave Zomato an entry point to extend beyond food into quick commerce, potentially positioning itself as a logistics player rather than just a delivery app.

But Anurag Singh isn’t buying this argument. He calls Blinkit “just an exit to private equity,” implying that Zomato overpaid to bail out investors. He also says that Zomato’s management is “just buying topline and creating a topline illusion,” meaning they’re using acquisitions to boost their revenue numbers instead of focusing on organic growth. His concern is that Zomato’s business model will keep burning cash for years. “This will be a constant cash guzzler,” Singh warns.

Another issue Singh raises is Zomato’s valuation. It’s currently around ₹1.4 lakh crore or ~$17 billion. For comparison, DoorDash—which operates in a much larger U.S. market—has a market cap of roughly $35 billion. Singh questions whether Zomato should be valued so highly, saying, “I haven’t seen any sector play where somebody’s going to reason out that an Indian replica of a US player is half the market cap of a US company.”

Damodaran has also commented on this valuation comparison. He noted that while DoorDash has larger average order values (AOV) and more mature online habits, Zomato faces different challenges and opportunities. “In India, time and traffic issues can give companies like Zomato a competitive edge. People are willing to pay for convenience here,” he explained. This creates a scenario where Zomato’s success may not rely solely on food delivery—it could become a broader logistics player that solves real urban problems.

Even with this potential, Singh remains unconvinced about the upside for investors. He predicts that “by 2030, people will still be sitting on 2-3x returns”—far less than what most expect from high-growth tech stocks.

Adding to the tension, Zomato’s recent quarterly results didn’t inspire much confidence. The company posted a profit decline of over 50%, frustrating investors who were hoping to see stronger performance.

Heavy spending on expanding Blinkit and battling quick-commerce competition were key factors.

So, what’s next for Zomato? Investors are caught between two narratives. On one side, there’s Anurag Singh’s view that the stock is overhyped and overpriced. On the other, Damodaran suggests that while the valuation may be steep, Zomato could evolve into something bigger—possibly a dominant logistics player in India’s future economy. As Damodaran himself said, quoting Keynes, “When facts change, I change my mind.” Investors might want to keep that in mind as Zomato’s story continues to unfold.

Drill baby drill

There’s been a lot going on in the oil sector lately, and I didn’t quite realize the full extent of it until I wrote about it on The Daily Brief recently. Since then, I’ve come across more insights, including a conversation with India’s oil minister, Hardeep Singh Puri, on CNBC. He made an interesting observation about Guyana that caught my attention:

But what does he mean by that? Why is Guyana’s oil discovery a big deal? To understand that, you need to know how OPEC came into existence and why they might be losing sleep over new oil discoveries in places they don’t control.

OPEC’s Rise and Control Over Oil Markets

In the 1960s, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Venezuela, and other key oil-producing nations created OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) to protect their interests. At the time, Western oil companies—referred to as the “Seven Sisters”—had a near monopoly on oil production, dictating terms to resource-rich nations. OPEC was formed to wrest back control over pricing and production.

Fast forward to today, and OPEC controls around 40% of global oil production and holds roughly 80% of the world’s proven reserves. That gives them significant market influence.

Later, OPEC+ was formed by including other major non-member producers like Russia and Kazakhstan to further coordinate production cuts or increases. But despite these efforts, their influence is weakening.

The reason? Oil is now being discovered and extracted in non-OPEC countries, like Guyana and Brazil.

Guyana, in particular, has rapidly scaled up production, thanks to major investments from ExxonMobil, and is projected to produce 1.3 million barrels per day by 2027.

This is outside OPEC’s control, and it dilutes their ability to manipulate global prices.

OPEC’s Efforts to Prop Up Prices

OPEC+ has been aggressively cutting production—by around 6 million barrels per day from 2022 through a series of cuts—in an attempt to reduce supply and push prices higher. But it hasn’t worked. Oil prices have been stuck around $72–73 per barrel.

Hardeep Singh Puri addressed this challenge head-on:

This presents a serious problem for oil-dependent economies. Saudi Arabia, for example, needs oil prices above $96 per barrel to balance its budget. According to Rory Johnston, an oil expert, the situation is even more challenging when you account for the kingdom’s Vision 2030 spending priorities. Johnston highlights that much of this spending is funneled through Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF), leading Bloomberg to estimate the fiscal breakeven price for Saudi oil to be over $100 per barrel.

Seems like since Saudi Arabia’s bet on WeWork failed, they’re now focused on squeezing every drop of oil revenue they can.

Why Aren’t Prices Rising?

OPEC’s struggles aren’t just about new competition from producers like Guyana. Several broader factors are keeping prices low:

1. Oil being discovered in new regions

Countries like Brazil, Guyana, and Canada have scaled up their oil production in recent years. With more oil flooding the market, OPEC’s production cuts are not enough to counterbalance this supply glut. This is creating a global surplus, which suppresses prices despite the output reductions.

2. Global demand might be weakening

The global economy isn’t growing as fast as expected, particularly in major oil-importing regions like Europe. Recession fears, tightening monetary policies, and sluggish industrial output are all contributing to softer oil demand.

3. China’s potential “peak oil” moment

China is a critical player in global oil markets. It imports vast amounts of crude to fuel its industries and vehicles, but that demand might have peaked. The country has been aggressively transitioning to electric vehicles (EVs). In fact, 60% of global EV sales happen in China, and by 2030, that figure might reach 75%. This shift is reducing gasoline demand. Additionally, China is replacing diesel trucks with LNG-powered trucks, further cutting demand for oil.

As Hardeep Singh Puri put it:

But it’s not just EVs. China’s construction sector, which consumes large amounts of diesel, has slowed down considerably. Combined with weak overall economic growth, this is putting further downward pressure on oil demand

OPEC’s control over oil prices has always depended on balancing supply and demand. But with so many variables at play—new discoveries, geopolitical shifts, and declining demand in major markets like China—their grip on the market is loosening.

If prices remain low, OPEC may need to extend or deepen production cuts. However, this strategy has limits. Many member countries have budget deficits to manage and can’t afford prolonged revenue losses.

In this increasingly complex game of oil geopolitics, no one holds all the cards anymore. As Hardeep Singh Puri put it:

“What happens if suddenly a lot of oil becomes available? Then it becomes more of a buyer’s market.”

And that’s exactly what we’re starting to see.

Active investing vs Passive investing

Aswath Damodaran recently reflected on the challenges facing active fund managers on his blog, where he analyzed U.S. equity markets and how investment strategies like small-cap and value investing have fared over the years. He noted that traditional strategies are struggling in today's market environment, which has become increasingly skewed towards large-cap, tech-driven winners like Apple and Nvidia. One line or should I say a bold statement that he says in the blog post is this:

Damodaran points out that passive investing is clearly winning against active investing. Active fund managers are struggling to beat the market, and there’s a simple reason why: they face a mathematical disadvantage.

Let’s break it down. Imagine all the money in the stock market. Some of it is managed passively (through index funds), and the rest is managed actively (by fund managers picking stocks). Together, active and passive investors are the market. Now, passive investors just track the market and incur very low costs. On the other hand, active managers try to beat the market by trading stocks frequently and analyzing companies, which involves higher costs—like fees, research, and trading expenses. After those costs, active investors, as a group, end up earning less than the market's average return.

In other words, it’s hard for active managers to outperform because they’re competing against each other while also carrying the extra burden of higher fees and expenses. That’s why studies show that, over time, passive funds—which keep costs low and simply follow market indices—often outperform actively managed funds.

This isn't just a theory. Damodaran notes that even in the U.S., where investment strategies like small-cap or value investing were once popular, most active managers have failed to consistently deliver better returns than their passive counterparts.

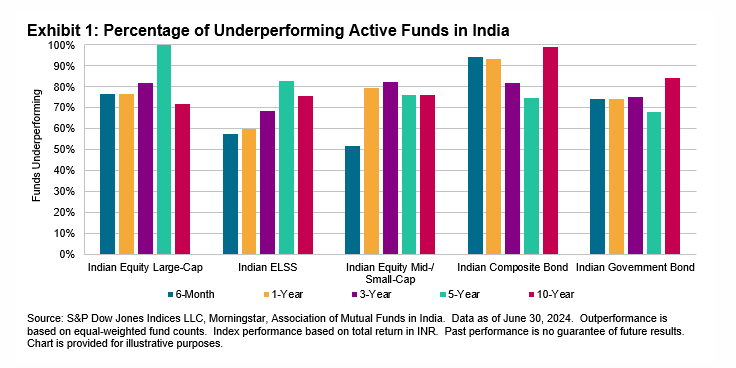

In India, the situation mirrors much of what Damodaran describes. According to the SPIVA report, Indian large-cap funds have severely underperformed their benchmarks. Over the past five years, 100% of large-cap funds failed to beat the index, and this declines to about 70% when looking at a ten-year horizon. Mid- and small-cap funds fared slightly better, but even there, more than half of them underperformed their benchmarks. Both on 5 year and 10 year basis.

These underwhelming results for active funds in India reinforce Damodaran’s argument: why pay high fees to active managers when a low-cost index fund can get you better returns?

However, the dominance of passive investing has sparked debate over its long-term effects on markets, particularly on price discovery. Price discovery is the process through which buyers and sellers set market prices based on new information. Critics worry that if too many investors blindly invest in passive funds without analyzing individual stocks, prices might become inefficient. Damodaran pushes back on this concern, explaining that markets naturally adjust. If prices were to become distorted, opportunities for profit would attract active investors who could correct those inefficiencies. He draws from economic theory, emphasizing that this balance between active and passive investing ensures that markets don’t become entirely inefficient.

Damodaran himself admits to being an active investor, not because he has special information or superior analytical tools, but because he enjoys the process.

Please let us know what you think of this episode 🙂

Once again great work.. The Daily brief has become my goto newsletter/podcast on weekdays and I look forward to Who Said what over the weekend. Kudos to the entire team...

Thank you Zerodha team for this informative and incisive analysis. Keep up the great work your team is doing. I enjoy reading all your publications like the daily brief and Who said what.