Who said what about overvalued markets, smuggling cigarettes, achieving AGI and the world ending

Hey everyone, welcome to another episode of Who Said What! This is the show where we take interesting comments, headlines, and quotes that caught our attention and dig into the stories behind them You know how every week, there’s a bunch of headlines that grab everyone’s attention, and there’s so much hype around them? Well, in all that chaos, the nuance—the real story—often gets lost. So that’s the idea to break things down.

Today, I’ve got four really interesting comments for you.

Are the markets overvalued?

I’m new to the markets. Most of the things that experts, commentators, or even my boss say tend to go over my head. This show is partly my selfish attempt to learn the nitty-gritty of markets while sharing whatever I pick up along the way. And one term I keep hearing is this: “Markets are overvalued.”

Every time the market falls even a tiny bit, this meme comes to mind:

The markets dipped again this week, which seems like the perfect trigger to talk about what experts are saying about valuations. Here’s a tweet I came across on this very topic.

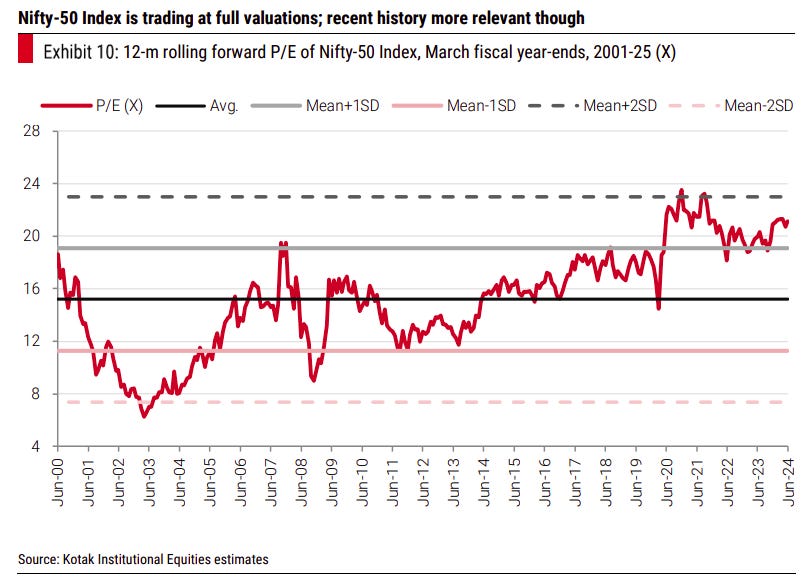

Sanjeev Prasad, MD of Kotak Institutional Securities wrote in a research report about markets being overvalued and it was a digestible read. When I say digestible, I mean it didn’t feel like Greek or Latin. He bluntly titled one section: Comedy—absurd valuations for so many sectors and stocks even now.

He didn’t hold back, pointing out that retail investors' focus on greed over fundamentals has driven valuations to ludicrous levels. Here are some of his key points:

Retail investors seem to be throwing caution to the wind.

Any random story about a sector or stock is enough to rally buyers.

Investors don’t really care about the fundamentals but the “dip”

Prasad used charts to illustrate how “narrative” stocks are trading at ludicrous price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios. For the uninitiated, P/E is a quick and dirty metric to gauge how much investors are willing to pay for a company relative to its earnings. It’s a handy tool, but it has its limits.

He says this: In our view, many ‘narrative’ stocks have a long way to fall, based on the true value of such companies. Many of them have corrected sharply in the past 3-6 months, but most are trading at absolutely ludicrous valuations

By "narrative," he refers to situations where valuations and growth expectations are driven more by compelling stories about future potential rather than by current financial performance. For example, this is often seen in sectors like EMS and capital goods.

And, it's not the first time he has said this. In June last year, he said the following:

In our view, the extreme euphoria among non-institutional investors has resulted in (1) steep increase in stock prices of mid-cap. and small-cap. stocks over the past 15 months….(2) distended valuations across sectors

Before that, in March of last year, he said the same thing: Euphoria, incorrect valuation principles, and unrealistic narratives [are] at play.

The problem with valuations—and why timing markets based on them rarely works—is that markets often don’t make sense in the short term. Valuations are a way to see how much people are willing to pay for a stock compared to its actual numbers, like profits or assets. But markets aren’t just about numbers. Markets are driven by a mix of fundamentals, liquidity, sentiment, and momentum, each of which can behave unpredictably.

Akash Prakash of Amansa Capital adds another layer to this conversation. He recently wrote about global markets, voicing concerns over elevated valuations—not just in India but particularly in the US in Business Standard. He said:

"If you look at the CAPE (cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings) ratio, the only time it has been higher was during the dot-com bubble of 1999-2000. On alternative valuation metrics like price-to-book or price-to-sales, we’ve already crossed those levels."

Now, what is the CAPE ratio? Like how the P/E ratio compares a company’s current stock price to its annual earnings, the CAPE ratio smooths out the earnings over a 10-year period and adjusts for inflation. This makes it less prone to short-term fluctuations and a better measure of long-term value. In simpler terms, it’s a way to judge whether markets are running too hot or too cold over time.

Here’s what the Indian CAPE ratio looks like, all thanks to Professor Rajan Raju for this data:

Prakash argues that high starting valuations significantly diminish the chances of robust long-term returns. He paints a stark picture:

"Can you really make good long-term returns from US equities when your starting point is arguably the most expensive in history? Financial history suggests this is a bad bet."

Interestingly, Sanjeev Prasad had also discussed valuations in a CNBC interview sometime back. He pointed out that headline valuation numbers can be very misleading. For instance, he explained:

"About 50% of the net profits in the Nifty come from low P/E sectors like banks, metals, and oil & gas. These sectors are trading at relatively modest valuations, but the rest of the market is extremely expensive on both an absolute basis and compared to history."

He didn’t mince words about “narrative stocks,” saying:

"Many midcap and small-cap narrative stocks have corrected by 20-50%, but their true value is often only 20-50% of their current market prices. There’s still a long way to go for these to align with reality."

So, are the markets overvalued? I am not an expert. But both Sanjeev Prasad and Akash Prakash make compelling cases that many sectors and stocks—whether in India or the US—are priced for perfection, if not beyond.

If you look underneath the indices there’s a lot of blood.

What do you think? Are the markets overvalued?

ITC is not happy

The Indian Express recently published an article saying that ITC wrote in a letter to the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence(DRI) that the smuggling of misbranded cigarettes from Southeast Asian countries into India is causing an annual tax revenue loss of Rs 21,000 crore, apart from helping finance terrorism.

I tried to find this letter but I couldn’t find it anywhere. But here’s what I did find—ITC in their last annual report had highlighted this number. They said that:

It is estimated that illicit trade causes an annual revenue loss of appx. ` 21000 crores to the Exchequer. With respect to other tobacco products as well, the revenue losses are significant since about 68% of the total tobacco consumed in the country remains outside the tax net.

India smokes roughly 12,600 crore cigarettes annually. However large this number may seem, India’s cigarette consumption is relatively low compared to some other countries. For instance, China’s cigarette consumption dwarfs India’s by a wide margin.

This leads us to an interesting statistic: India is the second-largest producer and consumer of tobacco in the world. But—here’s the catch—China produces more than half of what India does. China’s sheer scale in both production and consumption of tobacco makes India’s numbers look modest by comparison.

The ₹21,000 crore annual revenue loss due to smuggling isn’t just a number—it underscores a systemic issue rooted in India’s high tax regime on legal cigarettes. Tax rates on cigarettes in India are among the highest globally, accounting for nearly 50-60% of the retail price of most cigarette brands.

This creates a massive price disparity between legal cigarettes and smuggled ones. Smuggling becomes a lucrative trade when the price difference is this stark. For context, smuggled cigarettes often evade duties entirely, allowing them to undercut legitimate products by 30-40% in price.

This has a dual impact:

It dents companies like ITC, whose cigarette business operates within the legal framework but competes against these untaxed, smuggled products.

It deprives the government of significant revenue, weakening its ability to regulate the sector and fund public health initiatives.

So smuggling seems like a really big problem. Because it puts a dent in companies like ITC. So 21k crore seems like a big number—but is the real number? I don’t know. Is the number larger than this? Maybe. How did they even come up with this number? I have more questions than answers on this.

In their last to last annual report- they mentioned this number: 15500 crore. And, back in 2013, they said this number was more than 26,000 crore.

So, the annual tax revenue loss due to cigarette smuggling was more in 2013 than in the coming years? Does it mean that over the years smuggling has reduced? Like I said I don’t have any clue.

Please tell me if you know. I need to know..

Is AI a good thing or bad?

This line in Sam Altman’s blog post has been stuck in my mind ever since I spoke about this in the last episode, “We are now confident we know how to build AGI as we have traditionally understood it.”

AGI for context loosely means a machine being able to do whatever a human can. It keeps evolving.

I can’t stop thinking about why he would make such a statement. More so because I am a little terrified because I don’t fully understand what the hell is he going on about. Luckily, I came across a post by Ethan Mollick, a professor at Wharton, titled, “Prophecies of the Flood” and now I can’t stop thinking about how brilliantly he has articulated the good and the bad side of AI agents and all the hoo haaa around it.

Ethan begins by highlighting how AI leaders have hinted that we’re closer to AGI. Many of them claim to have unique insights into the future of AI. Basically, industry insiders know everything because they are closer to it. Here’s what he says: “Dismissing these predictions as mere hype may not be helpful. Whatever their incentives, the researchers and engineers inside AI labs appear genuinely convinced they're witnessing the emergence of something unprecedented.”

This brings me to another perspective I came across—a blog post by AI Snake Oil. While Ethan believes dismissing predictions is unhelpful, this post questions whether industry insiders are even credible predictors of AI’s future

They argue that it’s way too early to say AI progress is slowing down or that making bigger models is over. Sure, companies like OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic have hit some walls with their next-gen AI models, but that doesn’t prove scaling is dead—just that the easy wins are gone for now. What’s frustrating, though, is how quickly the narrative shifted from “scaling will lead to superintelligence” to “scaling is over, and now we’re all about inference scaling.” Inference scaling means optimizing how AI models use existing knowledge, rather than just making them bigger. The authors say this flip-flop shows that you shouldn’t trust what industry insiders are predicting about AI’s future.

And here’s why the post says you shouldn’t trust them: First, they’ve been wrong before—like when everyone was hyping up self-driving cars, but full automation still hasn’t happened.

Second, they don’t actually have some huge secret advantage. Even though insiders have access to data about their own models, it’s only useful for a few months. That doesn’t make them any better at guessing what’s coming years down the line. Third, these insiders have their own agendas like fundraising 🙂

Now coming back to Ethan’s comment that dismissing their predictions may not be helpful—he backs that up by showing various examples of how for example Google’s Deepmind was able to give him a 17-page report with 118 references on entrepreneurship and Ethan is a professor at Wharton himself and he said this:

It also is a bit shallow and does not make strong arguments in the face of conflicting evidence. So not as good as the best humans, but better than a lot of reports that I see. Still, this is a genuinely disruptive example of an agent with real value. Researching and report writing is a major task of many jobs.

That’s a big deal. There were various other examples that he gave, another one that I found interesting was when he pointed out how OpenAI’s new model, o3, has sparked intense speculation by surpassing major benchmarks. It’s part of a new generation of AI “reasoners” designed to take extra time to “think” before answering, significantly improving problem-solving abilities.

On the Graduate-Level Google-Proof Q&A (GPQA) test, o3 scored 87%, outperforming human PhDs who averaged 34% outside their specialty and 81% within it. On the notoriously difficult Frontier Math problems, where no AI had scored above 2%, o3 managed 25%.

As we grapple with AI’s implications, perhaps the bigger question isn’t whether AGI is near, but how prepared we are for the disruption it might bring

This time, it’s different?

The world is constantly changing. There’s a stark difference between 2015 India vs 2025 India. But, why the hell am I saying this? Ezra Klein, a New York columnist and the cofounder of Vox, recently wrote a piece in NYT saying the world is breaking down.

Here’s the intro of his piece, he writes:

Donald Trump is returning, artificial intelligence is maturing, the planet is warming, and the global fertility rate is collapsing.

To look at any of these stories in isolation is to miss what they collectively represent: the unsteady, unpredictable emergence of a different world. Much that we took for granted over the last 50 years — from the climate to birthrates to political institutions — is breaking down; movements and technologies that seek to upend the next 50 years are breaking through.

He’s basically saying that there are too many big changes happening all at the same time: Trump returning, AI boom, global warming, and the fertility rate going down. All these events put together he says are extremely frightening. He tweeted out saying, “Gonna be a wild decade”

Now, I agree—things are changing, and it does feel like we’re living in a whirlwind of events. But here’s my question: isn’t the world constantly changing? What makes this moment the moment to declare the end of stability, the beginning of chaos? What makes this change so fundamentally different?

Here’s a tweet I saw on similar lines:

The world is changing all the time. It’s only people who are fully attached to only one particular world-view who don’t see it. To claim that the world has remained somehow stable and unchanged for the last 50 years is just ridiculous.

Think about the early 2000s. The 9/11 attacks upended global geopolitics, sparking wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that reshaped the Middle East. The 2008 financial crisis sent shockwaves across the world, collapsing economies and leading to unprecedented government bailouts. At that time, people genuinely thought the global financial system was on the brink of collapse.

Or take 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Overnight, the world changed in ways no one could have predicted. Borders shut, economies froze, and millions of lives were lost. Yet, here we are here.

Ezra warns about the rise of AI and its implications, but haven’t we been through similar fears? In the 2010s, people worried automation would wipe out entire industries. Remember when everyone thought self-driving cars would make truck drivers obsolete by 2020? It didn’t happen that way. AI is advancing fast, sure, but isn’t that just another chapter in the technological evolution that’s been shaping the world since the Industrial Revolution?

This brings me to the idea of polycrisis, a term popularized by historian Adam Tooze. But not everyone likes this term— Historian Niall Ferguson said the polycrisis is “just history happening.”

Let me explain what it means. Unlike a single crisis, a polycrisis involves multiple, interconnected crises that amplify one another. Adam describes it as a situation where "the whole is even more dangerous than the sum of the parts."

Think about it: global warming isn’t just an environmental issue — it’s tied to food security, migration, and political stability. The rise of AI isn’t just a technological shift — it’s reshaping labor markets, geopolitical power, and even how we perceive reality. Fertility rate declines aren’t merely a demographic concern; they have long-term economic implications for growth and social security systems.

Each of these crises might be manageable on its own, but when they interact, the complexity can feel overwhelming. For instance, climate change exacerbates migration pressures, which in turn stress political systems already grappling with economic disruptions caused by automation or declining populations. It’s the entanglement of these crises that makes this moment feel uniquely unstable.

This helps frame why Ezra Klein’s piece resonates. It’s not just the magnitude of individual changes — it’s the way they’re all happening at once, creating a sense of cascading instability. The world might always have been in flux, but the speed and interconnectedness of these crises make it harder to navigate.

Yet, it’s worth remembering that the world of 2015 doesn’t look like the world of 2025. The world of 2000 didn’t look like the world of 2010, either. From the Industrial Revolution to the rise of the internet, humanity has always navigated transformational moments. What’s different now might be the speed and scale of these changes

So, maybe Ezra is right about one thing: this is a wild decade. But at the same time, isn’t this just another chapter in the constant evolution of human history?

- This is written by Krishna

Please let me know what you think of this episode 🙂

Hi, there is a typo in ITC article i think - it should be - china produces 2 and half times.

The AI evolution brings sanity to the genielike capabilities that are tossed about so casually. The writer cautioning that (1) Things evolve as do thought, what began as the solution or the super algorithm or God in human form faded some to open new areas, applications and at the other extreme disproving lovingly held insights and in its wakes destroying Industries, professions and businesses (2) In evolving intellectual constructs there are there are thoughts, ideas, feelings and sentiments whose life us merely 6 months or less (3) Not said but the fact is the rate of change today is steeper today than 50 years ago and hence implications of AI and prospects are still being understood

Great article.