Who said what about No Global Indian Giants, Bank Profit Illusions & India’s Trade Truth

Hello, I’m Krishna and welcome to Who said what?—the show where I dive into interesting comments from notable figures across the world, whether in finance or the broader business world, and explore the stories behind them.

Today, I’ll go over the comments from Uday Kotak and Uday Kotak again and Deepak Shenoy.

Uday Kotak says there are no global Indian companies

Uday Kotak recently said something that there are no global Indian companies:

And he’s right.

We’re a country of over a billion people, with a thriving startup scene and companies that do amazing things in IT, pharma, manufacturing—you name it. But when it comes to consumer brands that resonate globally, the cupboard’s pretty empty. You might think of TCS, Infosys, or Wipro, but those are IT service providers. They’re not the brands that someone picks off a store shelf in Berlin or walk into in New York.

Now, bollywood might be known around the world. Growing up, I used to think Maagi or Dairy Milk is an Indian company but how wrong was I. Even brands like Zomato or Ola, which have tried going international, haven’t really cracked it.

The reason behind this according to him lies in comfort and protectionism. Indian companies can thrive within the domestic market—one of the biggest in the world—and that removes the urgency to build truly global operations. Why battle it out on a global scale when you can make a healthy margin selling to Indians?

This comfort zone is a double-edged sword—it gives us thriving local champions but very few that can stand shoulder-to-shoulder with international titans.

All of this shows up directly in how we invest.

This Isn't Just About Branding—It Affects Your Portfolio

Neil Borate summed it up perfectly:

“Indian equity investors are starved for truly global companies… The solution is global diversification.”

Most of us, i.e. Indian investors tend to build portfolios heavily concentrated in Indian equities. That might feel diversified—after all, we might own stocks in banks, pharma, tech, and consumer—but that’s diversification within just one country. From a global investing standpoint, that’s not enough.

Finance theory tells us that a well-diversified portfolio shouldn’t just be diversified across asset classes but also across geographies. Why? Because economies don’t move in sync. When one country stumbles, another might thrive. Currency risks, policy shifts, demographic changes—all these things play out differently around the world. Spreading your investments globally helps smooth out risks and access opportunities you can’t get at home.

China Is a Case in Point

Let’s say you lived in China and only invested in Chinese stocks over the last 30 years. Sounds like a good bet, right? Huge GDP growth, global exports, massive infrastructure spending. But here’s the reality—since 1993, Chinese stocks have actually destroyed wealth.

I’m not exaggerating. The MSCI China index is down over that 30-year stretch. It’s returned less than what you started with—a total return of just 0.89x, meaning you’d actually be underwater after all those years.

In contrast? The MSCI India index has been a 13-bagger. That means Indian markets multiplied investor wealth 13.6x over the same period.

So yes, Indian investors have been lucky. But luck isn’t a strategy.

What Does “Global Diversification” Even Mean?

If you're new to investing, the term "global diversification" might sound intimidating. But it's a simple idea.

It means: don’t put all your investment eggs in one country's basket. Buy stocks or funds that give you exposure to markets outside India—through mutual funds, ETFs (exchange-traded funds), or international equity platforms. That way, your financial future isn’t entirely tied to how India performs.

If India booms, great. But if it slows down—even temporarily—you’re not completely exposed.

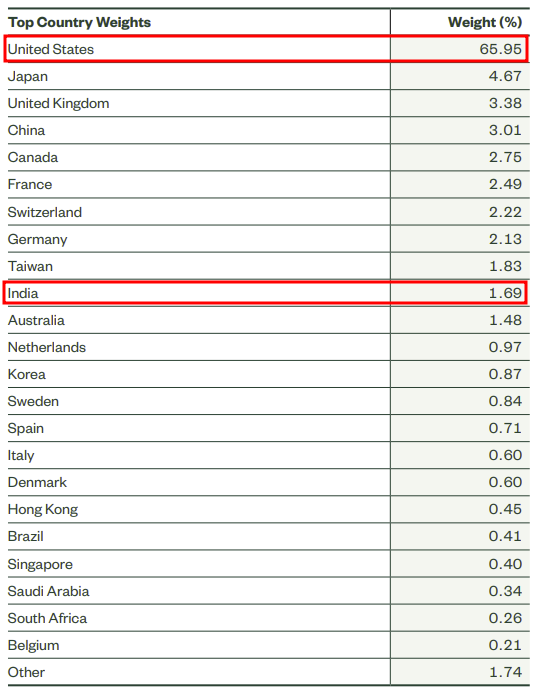

Look at the top country weights of an All Country World Index, which tracks global equity exposure. Over 65% of it is just the U.S. And, India? A tiny 1.69%.

Now, that doesn’t mean you should blindly mirror that weight in your own portfolio. But it does show you where the market thinks the value is being created.

The Global Consumer Is the Real Test

What Uday Kotak said isn’t just about global recognition. It was about what it takes to build truly world-class companies.

That’s what Indian companies need to strive toward. But until then, as investors, it’s on us to build portfolios that reflect where the world is—not just where we are.

Because while India is a great story, it’s not the only story. And as we’ve seen with China, even a great economic story doesn’t always lead to great market returns.

Uday Kotak says banks are not making money?

There’s another thing that Uday Kotak said this week, that honestly I couldn’t understand very well. Here’s what he said:

Now, if that sounds like greek and latin to you I understand. I asked Kashish from the team who claims to be banking expert to help me with this piece and he made sure that I gave him credit for this, so here’s his two seconds of fame.

What Uday Kotak is Really Saying

So here’s what’s happening: some banks are raising money by taking in wholesale deposits — large, lump-sum deposits from companies or institutions — and they’re paying around 8% interest for that money.

But banks don’t get to use all of that 8% freely. A chunk of it has to be set aside because of regulations:

CRR (Cash Reserve Ratio): This is money the bank has to park with the RBI. It doesn’t earn any interest.

SLR (Statutory Liquidity Ratio): This is money the bank must invest in safe government bonds — which usually offer lower returns.

Deposit Insurance: Banks have to pay a small premium to insure your money.

Priority Sector Lending: Banks are required to lend a portion of their funds to specific sectors like agriculture or small businesses — not always very profitable.

All of this eats into the bank’s actual usable funds. So even if they’re paying 8% on paper, the real cost ends up being more than 9%.

Now here’s the kicker — they’re giving out home loans at 8.5%.

So yeah — borrowing at 9%, lending at 8.5%. That’s a negative spread of 0.5%. In other words, they’re losing money on every rupee loaned out like this.

Why That’s a Big Deal

This difference — between what a bank earns on loans and what it pays on deposits — is called the Net Interest Margin (NIM). And for banks, this margin is everything. It’s their core revenue. Their bread and butter.

So when someone like Uday Kotak — one of the sharpest minds in Indian banking — points out that margins are going negative, it’s concerningt. He’s flagging a real issue with how sustainable the business model is right now.

But the reality is a lot more layered. Let me break it down.

1. Not All Deposits Cost 9%

Banks don’t just raise money from expensive wholesale deposits. They also have CASA deposits — that’s Current Account and Savings Account money.

Current accounts (used by businesses) don’t pay any interest at all.

Savings accounts pay just 3–4%.

This is cheap money. So when you mix this with the higher-cost wholesale deposits, the overall “blended” cost of funds is actually lower than 9%. So no, banks aren’t always borrowing at 9% across the board

2. Home Loans Are Just One Part of the Puzzle

Uday’s tweet compares a 9% deposit cost to 8.5% home loan rates. That looks bad on paper — but remember, home loans are just one part of what banks do.

Banks also lend money through: Personal loans (12–14% interest), Credit cards (30–40%), Car loans (8–10%), MSME and business loans (10–12%). Gold loans, loan against property, and more

These other loans bring in much better margins. So even if home loans are loss-making, the overall lending book might still be healthy.

So, Where’s Uday Coming From?

Uday Kotak not just randomly venting. This post comes at a time when something weird is happening in Indian banking. And CNBC recently laid it all out quite well.:

Loan rates are falling. Deposit rates aren’t.

Why’s that happening?

Because many bank loans today are tied to external benchmarks — like the repo rate, which is set by the RBI. These are called EBLR loans (External Benchmark Lending Rate). So when the RBI cuts the repo rate, banks have to lower the interest they charge on these loans.

But here’s the catch: deposit rates (what banks pay you) aren’t falling. Not by much, anyway. That’s the mismatch.

And this is despite the RBI pumping ₹7 lakh crore of liquidity into the system through all sorts of tools — like swaps, bond purchases, repos, etc. Normally, all that extra money should push deposit rates down. But it isn’t. Why? There are a lot of reasons, but experts are pointing fingers in this direction.

Mutual Funds

People just aren’t putting money in fixed deposits the way they used to. Instead, they’re investing in mutual funds. Now technically, this money still ends up in the banking system — mutual funds don’t keep it under their mattress. They park it in current accounts with banks.

But here’s the twist: this money is super unstable. Mutual funds move their money in and out daily — to buy stocks, redeem units, pay out dividends. So even if the money’s there today, it might vanish tomorrow.

And that’s a problem.

Because banks can’t give out a 20-year home loan using money that might disappear next week. That would be reckless. This situation is what’s called an Asset-Liability Mismatch (ALM). Basically: if your funding is short-term but your loans are long-term, you’ve got a risky setup.

So, banks go back to what’s stable: wholesale deposits. But again — those are expensive. That’s what Uday Kotak was talking about.

What Others Are Saying

Here’s what Deepak Shenoy had to say:

“I think bank NIMs must come down, from the 3.5–5% levels down to 2.5% eventually... The time for lazy banking is over. Margins will compress. The winners will come from volume and ability to raise liabilities well.”

“Banks crib about regulation but most don’t even take opportunities to lend well, which is why NBFCs even exist.”

He’s basically saying that the good old days of fat margins are probably over. Now, banks will have to win by being smarter — scaling up, managing risks better, and attracting more deposits, not just riding on high margins.

He also calls out a few things that banks need to do better:

Rethink priority sector lending rules.

Ease SLR requirements (those forced investments in government bonds).

Stop acting like all their loans are linked to repo — they’re not.

Use risk management tools like OIS (interest rate swaps) more effectively.

His message is margins will shrink, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. The banks that evolve will still do just fine.

Srinivas Rajan, Chairman of Union Bank, added another layer to this:

What he’s saying is that the top 3–4 big banks have taken over half of all new business. Everyone else — including smaller public sector banks — is fighting over what’s left.

And when you’re smaller, with fewer customers and less brand power, you don’t get to set rates. You just take what the market gives you. So if the big banks are struggling on margins, the smaller guys are getting crushed.

So, Are We in Trouble?

Not really. But things are getting tighter. Uday Kotak’s tweet is more of a warning. Margins are shrinking, yes. But that doesn’t mean banks are doomed.

As Deepak says, this is just the end of an easy phase. The banks that adapt — by building a strong base of cheap deposits, pricing loans better, managing risk smarter — they’ll still do well.

The question is: who’s ready for this new world, and who’s still clinging to the old one? We’ll find out soon enough.

Is India’s trade stable?

I came across a tweet thread from Deepak Shenoy the other day, and it started like this:

"India's current account deficit is only $11 billion in the Oct–Dec quarter. For FY2024–25, it's only $37 billion. This is good; the rupee fell, but the problem was FPI flows and speculatory rupee trade, not fundamental trade flows."

When I first read this, I was a little lost. It sounde like one of those updates packed with numbers and jargon that you scroll past because you're not sure what it all means. Current account, rupee falling, speculative trade?

So I decided to dig in. What exactly is the current account deficit? Why is it considered "good" in this case? And what’s really going on with the rupee?

What Is the Current Account, and Why Does It Matter?

So the first term that pops up here is “current account deficit.” Think of the current account as India’s report card for how much money it’s earning from and spending on the rest of the world. If we’re exporting goods and services, or getting money from Indians working abroad, that’s income. If we’re importing oil, gold, electronics, or paying profits to foreign investors, that’s spending.

When we spend more than we earn, the gap is called the current account deficit, or CAD for short. And according to Deepak, India’s CAD in the Oct–Dec 2024 quarter was $11 billion. Over the whole financial year, it’s expected to be around $37 billion.

At first, this sounds like bad news. Deficit = bad, right? But Deepak says this is actually “good.” So naturally, I wanted to understand: how?

Where the Money Comes From, and Where It Goes

To understand this better, I looked into how that $11 billion number comes together. India imports a lot of stuff—especially things like oil, gold, and electronics. In the 3rd quarter, we imported about $79 billion worth of goods. That’s money going out.

On the other hand, we also export services. Indian companies in IT, consulting, financial services, and more send their skills abroad and get paid in dollars. That brought in $51 billion.

So when you put the two together—exports minus imports—you get a trade deficit of about $28 billion.

But here’s where it gets interesting.

Indians living abroad—doctors, engineers, nurses, construction workers, students, software pros—sent back a record $36 billion in remittances. This is money they earn in places like the US, UAE, UK, and Singapore, and send home to support families, build homes, or invest.

And that money is a huge inflow for India. In fact, it’s so large that it completely cancels out the trade deficit.

So at this point, you might think: okay, trade deficit of $28 billion, offset by $36 billion in remittances—does that mean we’re in surplus?

Well, almost.

So Why Is There Still a Deficit?

Even after the trade and remittances kind of balance out, there’s another piece that drags the numbers back down: investment income.

Here’s what happens. Foreign investors who’ve put money into Indian companies expect returns. They get paid in the form of dividends—a share of the profits. In 3rd quarter alone, Indian firms paid out $19 billion in dividends to foreign investors.

At the same time, India also earns some dividends from investments it holds abroad—around $4 billion. But that still leaves a net outflow of $15 billion.

So if you started with a $5 billion surplus from trade + remittances, and then subtract $15 billion in investment income going out, you land at a $10 billion deficit—which is roughly` what the RBI reported as $11 billion.

And now Deepak’s tweet starts to make more sense. The deficit isn’t coming from the usual culprits like too much oil or too many iPhones. It’s from paying foreign investors their share of profits—which is actually a sign that India is open for business and attracting capital.

So... Why Did the Rupee Fall?

This was the part of the quote that really caught my attention:

“The rupee fell, but the problem was FPI flows and speculatory rupee trade, not fundamental trade flows.”

Basically, when foreign funds invest in Indian stocks or bonds. These are short-term investments, and they can come and go quickly. And that’s exactly what happened. In the 3rd quarter, foreign investors pulled out $11 billion from India. That’s money being converted from rupees back into dollars, which increases demand for dollars and puts pressure on the rupee.

On top of that, currency traders—the speculators—started betting that the rupee would fall even more. So they began selling rupees and buying dollars, further pushing the rupee down.

Shenoy’s point here is subtle but important: the rupee didn’t fall because we were buying too many goods from abroad. It fell because of how financial markets reacted—to global interest rates, risk perception, and other short-term factors. The fundamentals were actually strong.

How Did India Handle It?

To prevent the rupee from falling even more, the RBI stepped in and did what central banks do during such times: it sold dollars from its foreign exchange reserves.

The RBI sold $37 billion from its reserves in this quarter. That’s a big move—and it worked. It stabilised the rupee and helped balance the outflows caused by investor exits and speculation.

Deepak sums it up neatly: “This balances the payments.”

The money that left the country was matched by the dollars the RBI sold. So the overall balance of payments stayed in check.

One More Quirk: Gold

There’s one last thing Deepak pointed out that I found fascinating. India imported $19 billion worth of gold in the same quarter. That’s a huge chunk of our import bill.

But here’s the catch—unlike oil or electronics, gold isn’t something we “consume” in the usual sense. We buy it as a way to store wealth. Deepak argues that this isn’t really a “current account” item in the traditional sense—it’s more like a financial investment.

And if you take out the gold imports from the equation, India would’ve actually had a $8 billion current account surplus.

That’s wild.

Please let us know what you think of this episode 🙂

NIM Will Contract Further no doubt about it very well explained.

This is fantastic insight, loved it. One quick question - why should gold be removed from CAD? while people use it as a saving, money has still gone out of India to buy it, hence should still be considered right?