Who said What about India’s middle class, India’s growth, US-China war and more

Sorry to everyone who watches this show—we couldn’t get this out on Saturday. If you notice the delay, you can tell me in the comments- I'll make sure my manager sees it. Anyway, I’m Krishna and welcome to Who Said What?—the show where I dive into interesting comments from notable figures across the world, whether in finance or the broader business world, and explore the stories behind them.

Today, I’ll go over the comments from Saurabh Mukherjea, Prashant Jain, and a couple of more people.

Saurabh Mukherjea on why middle class is in a crisis

Saurabh Mukherjea recently made a headline because he said that India’s middle class is 'borrowing to survive'.

In his podcast, Saurabh said this:

“Our research suggests that five to ten percent of middle-class India is in a debt trap. A debt trap is when people with modest incomes have taken on multiple loans which they’re never going to be able to repay… it’s reasonably easy to show that there are five to ten percent of middle-class Indians who’ve taken on multiple loans that they’ll never be able to repay.”

That’s quite alarming, especially coming from someone like him. But is this just a temporary blip post-COVID, or is it pointing to something more persistent and structural?

Who is the "Middle Class" in This Conversation?

See, Saurabh when talking about middle class—he’s going strictly by income data. According to him, based on income tax filings, India’s middle class includes households earning between ₹5 lakhs and ₹1 crore per year. That’s a pretty wide range, but what’s interesting is that this group makes up around 40 million families and contributes roughly 70% of the country’s income tax collections. So, these are people like us—most people reading or listening to this probably belong to.

This group is often held up as the backbone of India’s consumption story. Which is exactly why the idea of them being financially stretched raises eyebrows.

What Does a Debt Trap Actually Look Like?

The term “debt trap” is thrown around a lot, so let’s break it down into what it really means. Imagine someone earning ₹12–15 lakhs a year. But then you layer on a home loan, a car loan, one or two personal loans, and a few active credit cards. That by itself isn’t unusual—many families use loans to build assets or manage large expenses. The problem starts when income growth stalls while expenses rise, and the only way to make ends meet is by borrowing more. Or worse, using one loan to repay another.

At this point, your debt isn’t helping you grow—it’s just helping you survive. That’s the classic definition of a debt trap. And Mukherjea believes that up to 10% of middle-class families are already in this situation.

Now, some may argue that 5–10% doesn’t sound like much. But when you remember we’re talking about a middle class that covers around 150 million people, even the lower end of that estimate translates to several million households. That’s not a small problem.

How Did We Get Here?

According to Saurabh, there are three big reasons this debt build-up has happened.

The first is stagnant income growth. Based on income tax data, average incomes for middle-class taxpayers have more or less flatlined at around ₹10.5 lakhs for the past 10 years.

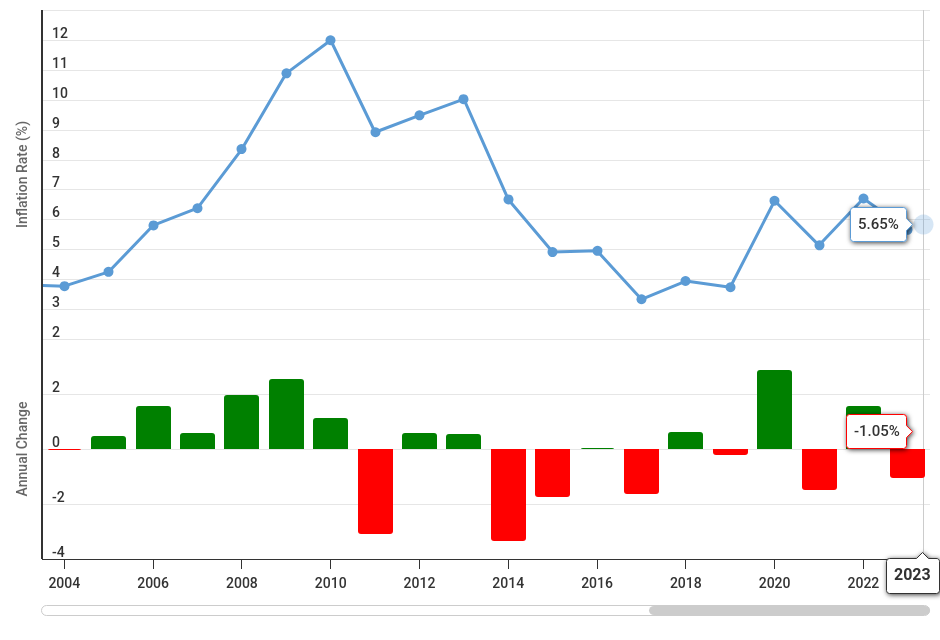

That’s nominal income. When you adjust for inflation, incomes have actually gone down. So while the cost of living has moved steadily upward—tuition fees, healthcare, rents, groceries—household earnings haven’t kept pace.

The second is the availability of easy credit. Over the past decade, retail loans have exploded. Credit card usage has tripled since 2021. Personal loan growth was clocking over 30% annually until very recently. Lenders were aggressively pushing credit, and a lot of middle-class households took it. In fact, according to RBI data, personal loans and credit card loans now make up 11% of all bank credit—almost triple what it was a decade ago.

The third issue is what kind of borrowing this is. According to credit bureau data, nearly 21% of borrowers are classified as subprime—meaning they have low credit scores. And among these subprime borrowers, close to half the loans are for consumption: not for homes or cars, but for living expenses. This kind of borrowing—taking loans to fund your current lifestyle—is a clear warning sign. When you're borrowing to invest in an asset, that’s one thing. But when you're borrowing to keep your head above water, it gets dangerous fast.

But this isn’t just a borrowing story—it’s also about what’s happening to savings. And here again, Saurabh pulls no punches.

“The RBI’s data and the RBI itself is repeatedly telling the public that net household savings — net of borrowings — as a percentage of income is at its lowest level in 50 years… That’s a major challenge. And what’s even more tragic, if you look at the data, over the last 20 years, the growth in household balances in savings accounts has steadily diminished, from around 20% to maybe 10% now. So Indian households have done things like shift their savings away from savings accounts and into the stock market… in fact, small-cap funds at one of the most overvalued junctures in Indian history.”

Are People Really Borrowing to Invest?

Now are people borrowing to invest, this is where things get especially uncomfortable.

“There’s growing data that households have borrowed money to invest in the stock market. In fact, the former chairman of ICICI, K.V. Kamath, said in an Economic Times interview a couple of months ago that there is evidence that households have borrowed money to invest in the stock market… We went to a prominent high street bank in a [U.P.] district. We saw an illiterate man come and take a 10 lakh loan from the bank, and he said he would invest that money in futures and options in the stock market.”

The Bigger Picture

So what happens when a sizeable portion of the middle class is under financial strain?

One, consumption slows down. If households are spending more of their income servicing debt, they’re spending less on everything else—appliances, travel, even school fees. That impacts business revenues, which in turn affects jobs and investments.

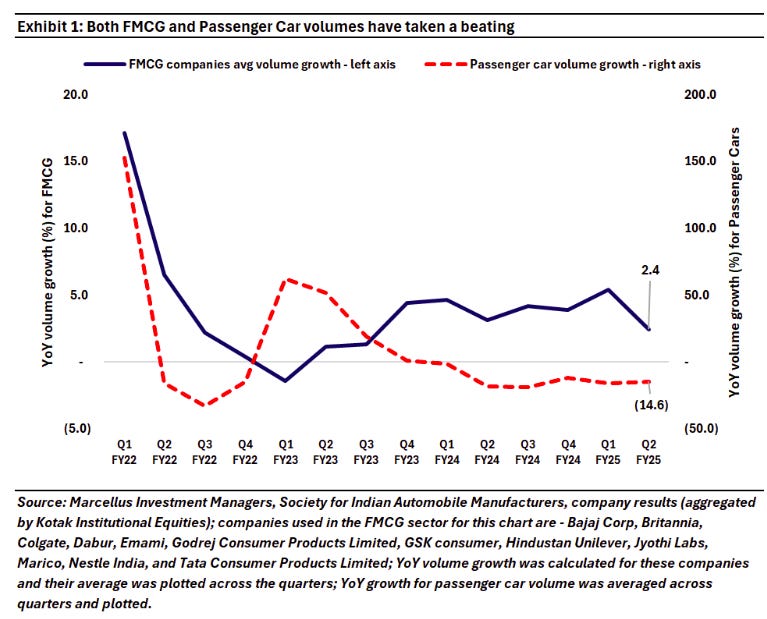

We are already seeing this happen, consumption has started to go down. The management of big FMCG cos have been constantly saying this for the past year.

Two, defaults rise. We’re already seeing early signs of this. Credit card NPAs are above 2%, personal loan defaults are inching up. These are still manageable—but the direction matters.

Three, policy blind spots emerge. Saurabh makes an important point: despite paying most of the taxes, the middle class isn’t politically powerful. They make up maybe 10–15% of the voting base. And many don’t even vote. So policies tend to cater either to the very poor (through welfare schemes) or to the very rich (through capital-friendly reforms). The middle class often ends up squeezed in the middle—without the subsidies of the poor or the capital of the wealthy.

So Is This Really a "Trap"?

That’s the nuance. Not everyone with a loan is in trouble. Many borrowers are using credit responsibly, for assets, business, or emergencies. But what Saurabh is pointing out is a structural issue. A significant number of households are now using credit as a substitute for income. That’s when debt becomes a trap.

Saurabh’s not saying the economy is on the verge of collapse. What he’s doing is pointing out a slow-burn issue that doesn’t get enough attention.

India’s middle class is under pressure. Incomes haven’t grown meaningfully. Costs have gone up. Credit has filled the gap, but in some cases, it’s starting to backfire. If even a small percentage of this group is trapped in debt, it deserves a closer look—not just from policymakers, but from all of us who see ourselves as financially literate citizens.

Prashant Jain on where India stands

Prashant Jain, the former CIO at HDFC Mutual Fund, and now co-founder of 3P Investment Managers recently gave a speech. Now, why should anyone care to listen to him? Well, he has over three decades of experience in Indian equities and he was among the first in the country to manage over one lakh crore in equity funds. When someone with that kind of track record in the markets offers insights, it’s worth paying attention.

He touched on multiple topics—India’s growth story, corporate profitability, nominal GDP, interest rates, research & development (R&D), and how all of these feed into market valuations.

Let’s begin with the broad economic perspective he offered:

Now, nominal GDP might sound a little bit fancy. All it really means is the total value of goods and services produced in the economy, measured at current prices—that is, including inflation. If in 2005 a cup of coffee cost 10 rupees, but today it costs 20, that price jump is part of how nominal GDP grows. In earlier decades, India’s inflation was much higher, so our nominal GDP growth could clock 15–16%.

It wasn’t necessarily that we produced vastly more stuff; a portion of it was simply higher prices. Today, with lower inflation, nominal growth naturally settles into that 10–12% band.

He connects this directly to corporate profitability:

“India’s corporate profits to GDP ratio is now broadly around 6%. …When I look at corporate profitability across sectors, I find very little scope for margins to improve …I would find it very difficult for corporate profits to materially outgrow the nominal GDP growth in India.”

In other words, he doesn’t expect India Inc. to give profits well above 10–12%. Corporate profit as a share of our economy is already near historic highs—around 6–7%—which is a stark jump from the rock-bottom 1% ratio we saw near the pandemic lows.

Here’s a neat bit of nuance: after a crisis like COVID, profits often appear to rocket upward because they’re rebounding from a depressed base. Prashant’s caution is that, once companies have normalized to pre-crisis levels, you rarely keep seeing that same breakneck profit expansion. He’s basically reminding investors that you shouldn’t expect 25% profit growth each year just because you got 25% in the immediate aftermath of COVID.

He also made a statement on R&D that seems quite fair:

“It is also interesting to note that India does not have any nonlinear genuinely R&D-driven innovative businesses. So I think unlike the US where profits have grown far faster than their economic growth, I think in India that is quite unlikely.”

Now, “nonlinear R&D” might sound like greek&latin or maybe it’s just me. But the gist is this: if you look at the biggest U.S. success stories— Apple, Google or Pfizer—they’re spending heavily on research, building patented technologies, brand-new drugs, or advanced hardware. That lets them outrun the broader economy’s pace by a wide margin. Think of Apple’s iPhones revolutionizing the entire mobile industry or Amazon’s breakthroughs in cloud computing.

In India, we do have innovative companies, but country-level spending on R&D, as a percentage of GDP, is much lower. See the chart on the screen that shows how India invests less than 1% of its GDP on research, whereas some countries go beyond 4 or 5%.

Now, onto interest rates:

“As inflation in India has moved lower, our cost of capital has also drifted lower… I have spent my entire career tracking the gap between US and Indian interest rates at 4–6%. And currently that gap is running between 2–2.5%.”

That sounds a little technical, but it’s actually quite straightforward. If you take a loan at 8% in India while U.S. interest rates hover around 4%, the gap is 4%. As India’s inflation improved, our rates dropped closer to global norms, which meant that gap could shrink to around 2% or 2.5%. In practical terms, when interest rates are lower, stocks usually become a relatively more appealing investment. You don’t get as much from “safe” bank deposits or government bonds, so more people are willing to pay higher prices for equities. That’s one of the reasons India’s stock market might sustain P/E (price-to-earnings) multiples that seemed rich a decade or two ago, but now look justifiable.

But Prashant Jain also calls this current market “boring.” Yes, “boring.” He explains that, post-COVID, many undervalued sectors (like public-sector banks, power utilities) have already soared, while expensive consumer-focused stocks have corrected a bit, so everything’s converged to fair value. If you’re an active fund manager, it’s less exciting because you don’t see huge pockets of overvaluation or underpricing—most things are in a middle zone. For new investors, this means we might be in a period where you can’t just throw a dart at the market and get huge returns on “dirt-cheap” plays or avoid obviously overheated darlings.

Finally, what about the bottom line for long-term returns? Prashant believes:

“If you take a 3–5 year view, …the Nifty …should be very close to the nominal GDP or the profit growth rate which is about 10–12% a year… Many of us will find this extremely disappointing… but those high returns [in the last few years] were primarily because of a much lower base set during the COVID crisis.”

He’s basically saying don’t expect the same post COVID returns forever. If you’re used to annualized returns of 20 or 30%, that’s probably unrealistic in a steadier environment. But 10–12% is not shabby—especially when bank fixed deposits, after taxes, might take you over a decade to double your investment, while equities could do it in about six or seven years if they keep compounding.

He is telling us India’s growth story is healthy and stable, but we shouldn’t confuse a healthy story with the expectation of “rocket-fuelled” profits.

The U.S. is Becoming More Like China — And That’s No Accident

Michael Froman, former U.S. Trade Representative and now President of the Council on Foreign Relations, recently made a pretty striking observation: the U.S., after decades of trying to get China to adopt American-style capitalism, is now turning around and adopting the same policies it once criticized China for using.

For years, the assumption in Washington was clear: if we just bring China into the global economic system—let them join the WTO, open up markets, reduce tariffs—they’ll eventually start to look more like us.

More private sector, less state control. More free trade, less protectionism.

But that’s not what happened.

Froman argues that instead of China moving closer to the U.S. model, it's the U.S. that's moving closer to China’s. He calls it “Chinese policy with American characteristics.” The idea is that the U.S. is now embracing industrial policy, state subsidies, protectionist trade measures—all things it once lectured Beijing against.

So what changed?

Back in the ’90s and early 2000s, China genuinely seemed to be liberalizing. Leaders like Jiang Zemin and Zhu Rongji cut back on state-run enterprises, encouraged private business, and integrated China into the global economy. Joining the WTO in 2001 was seen as a turning point.

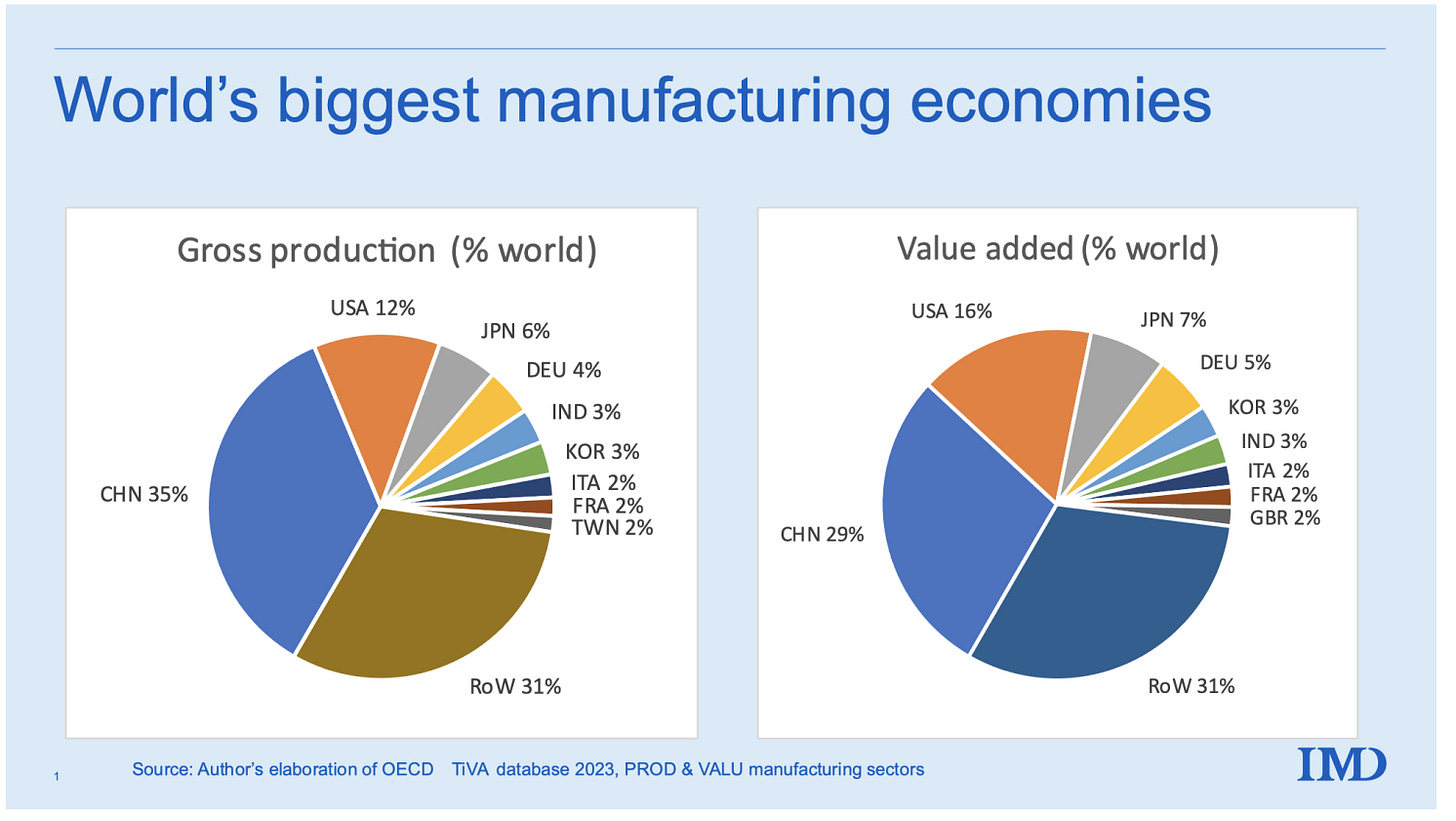

But that momentum slowed—and then reversed. Under Hu Jintao and especially Xi Jinping, China leaned back into state-driven development. The government supported massive homegrown companies, poured money into key sectors, and built up global dominance in manufacturing. By 2023, China accounted for nearly 30% of global manufacturing output. That’s three times its share in 2004.

Meanwhile, the U.S. kept pushing China to “play by the rules” — open up, cut subsidies, allow more competition. But none of that really worked. So American policymakers started to flip their own script.

Starting with Trump, the U.S. raised tariffs on Chinese goods from 3% to 19%. Biden didn’t reverse that — he kept the tariffs, and in some cases added more. Investment restrictions followed: Chinese money flowing into the U.S. dropped from $46 billion in 2016 to under $5 billion in 2022. Washington also started limiting how much U.S. companies could invest in China.

Then came the real shift — large-scale industrial policy. The U.S. government started spending serious money on homegrown manufacturing and tech through big bills like the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act. Combined, they’re worth over $1.6 trillion. In short: the U.S. is now in the subsidy game too.

Some policymakers have even floated the idea of requiring Chinese companies to set up joint ventures and share technology if they want to operate in the U.S. — which is exactly what China used to demand of American firms.

The big question now is: will any of this actually work?

Froman is cautious. He points out that China has certain advantages the U.S. doesn’t — the ability to channel capital quickly, a political system that can stay focused on long-term goals without interruption, and tighter state control over the economy.

In contrast, U.S. industrial policy has to navigate shifting politics and election cycles. Trump, for example, has already said he wants to repeal the CHIPS Act, despite its goal of boosting domestic semiconductor manufacturing.

Even on tariffs, the record isn’t great. A study by the Federal Reserve found that Trump’s tariffs in 2018 actually hurt U.S. manufacturing jobs and raised prices for producers. About 75,000 factory jobs were lost due to downstream effects.

So what’s the takeaway?

Froman’s argument is that China has already won the battle over which economic model is shaping the world. Not because it became more like the U.S.—but because the U.S. is becoming more like China. Countries around the world are now copying Beijing’s approach: protect domestic industries, use state subsidies to build national champions, and control capital flows more tightly.

That post-WWII, rules-based order built by the U.S.? It’s being re-written. And not by American design—but by China’s quiet persistence.

As Froman puts it: “Washington is already living in Beijing’s world.”

A barbell rally; ditch some deadweights

Sanjeev Prasad, MD of Kotak Institutional Securities, isn’t the loudest voice in the Indian market, but that’s exactly why he’s worth listening to. In a space full of noise, there’s a measured quality to his writing that makes you stop and think — not react.

I had covered one of his notes in one of the previous episodes where called the valuations in the markets absurd for a bunch of sectors and stocks.

His latest strategy note picks up on something a lot of people have been feeling lately: this rally doesn’t feel normal. The Nifty’s at a high, sure. Smallcaps have bounced hard. But it doesn’t feel like everything’s rising for the same reason — or even rising together. Sanjeev puts a name to it: a barbell rally.

What’s he mean by that?

On one side of the market, you’ve got the usual suspects doing well — large-cap financials. Banks, NBFCs, insurance companies. Stuff that might not be flashy, but feels stable.

On the other end? It’s the narrative names. Mid- and small-cap stocks that were completely out of favor six months ago — now suddenly leading the charge. But not because earnings have improved. Not because business fundamentals changed. Mostly because sentiment turned.

And here’s where Sanjeev is sharp. He’s not falling in love with either end of this barbell.

Yes, the BFSI space still looks okay from a valuation standpoint.

Banks are still trading at 0.8 to 1x book in some cases — hardly euphoric. But even here, there are cracks. Credit growth has slowed. Net interest margins are compressing. And credit costs are inching up. These aren’t red flags yet — but they are reminders that even the “safe” end of the barbell comes with its own baggage.

Then you turn to the other end — the frothy stuff.

Some of these stocks are being priced as if they’ll deliver huge profits in the future — but there’s no real sign that their actual earnings are improving. They’re trading at 25 times what analysts think they'll earn two years from now, and at three times the value of everything they own (their book value). That’s expensive. Especially when there’s no clear evidence that business performance is catching up to justify those high prices.

This isn’t exuberance based on delivery — it’s more like hope riding momentum. And when Sanjeev points out the valuation gap between these names and some of the larger, more proven ones, it’s hard not to raise an eyebrow. The disconnect is real.

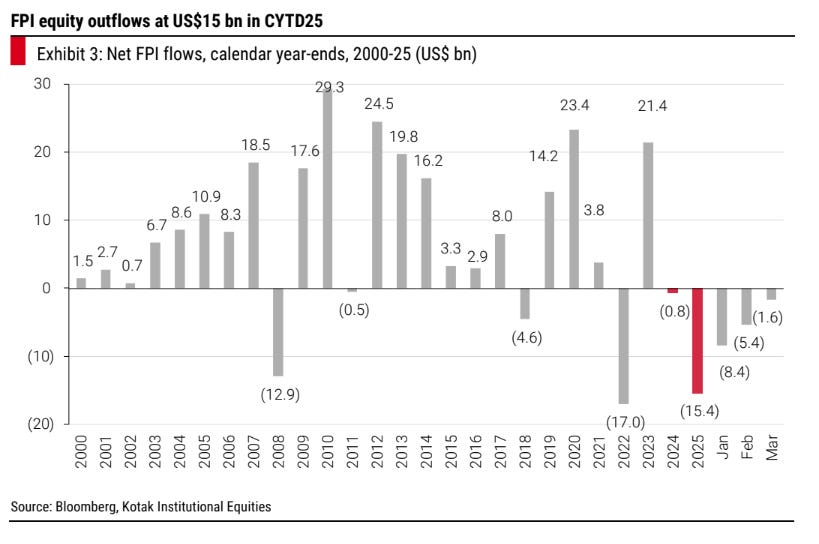

The broader environment doesn’t help either. Earnings downgrades are starting to creep in — especially in defensives like FMCG, IT, and even oil & gas. Yes, foreign investors have been net buyers in recent days, but it’s been a choppy year for FPI flows. And across sectors, valuations are running rich. In Sanjeev’s words — and you can feel the fatigue behind it — the market seems to be “moving on fumes.” A bit of hope, a bit of FOMO, and not a whole lot of visibility.

So what’s he really saying?

Don’t get carried away. Just because parts of the market are running doesn’t mean you have to run with them. Stick to the businesses you understand — the ones that earn real money, compound steadily, and don’t need narrative tailwinds to justify their price. That might still include parts of BFSI. And if you’re holding onto names where the only thing working is the chart and the buzzword — it might be time to let those go.

Please let us know what you think of this episode 🙂

This is the best write up I read in whole week even the daily briefs are great. But this one cuts through the noise.

Great Work as usual!