Who said what about Global Shipping, Declining Dollar & Banking troubles

Hello folks! I’m back, I hope you noticed my absence 🙂

Welcome to Who said what, I’m Krishna and this is the show where I dive into interesting comments by notable figures from across the world—whether it’s finance or the broader business world—and dig into the stories behind them.

Today I have three very interesting comments.

Where are we headed?

Ryan Petersen, CEO of Flexport, recently said this.

That’s not just some technical logistics number. That’s a sign that one of the most important supply chains in the world is suddenly seizing up. Now, Petersen runs Flexport, a major logistics company that moves goods around the globe. If anyone can see the cracks forming before the rest of us feel it, it’s him.

Let me set some context.

Almost everything you use—your phone, your clothes, even your couch—probably got to you via a shipping container. About 80% of all global trade by volume moves by sea. These containers are loaded at factories, stacked onto ships, cross the ocean, and then get hauled inland on trucks or trains. It’s a slow but incredibly cheap system.

Compared to flying goods by air, shipping by ocean is about 20 to 50 times cheaper. If ocean freight didn’t exist, the entire structure of global trade would collapse. A company like Apple could never manufacture an iPhone in China and sell it in California for a reasonable price without it.

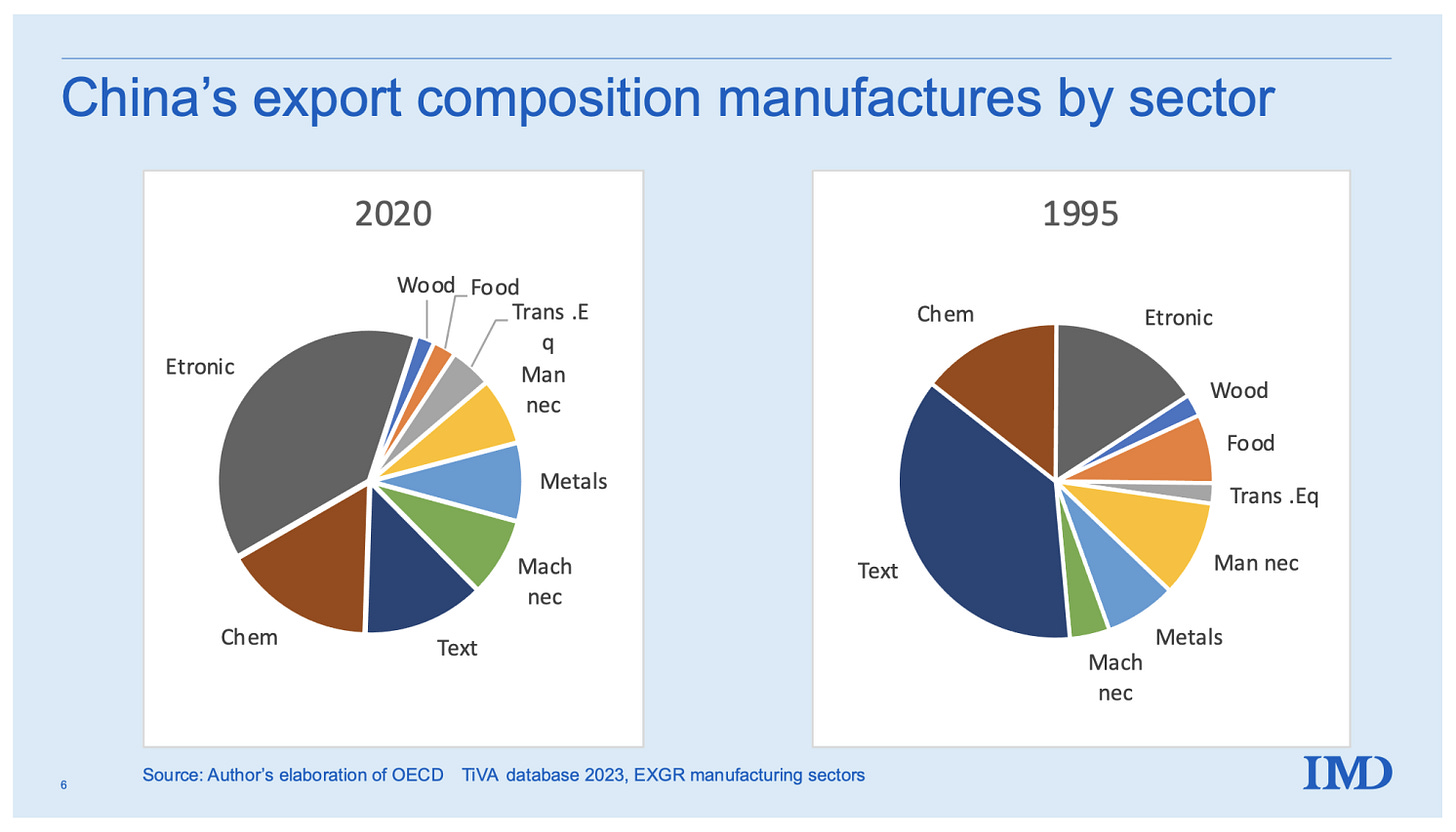

And China sits at the heart of this system. It’s the factory of the world, producing everything from electronics and toys to tools and furniture.

The U.S. imports more goods from China than any other country. That’s why what’s happening right now is so serious.

On April 2, the U.S. imposed a new wave of tariffs. So, if something cost $100 before, it might now cost $140 or more just to get it through customs. Importing from China has suddenly become brutally expensive.

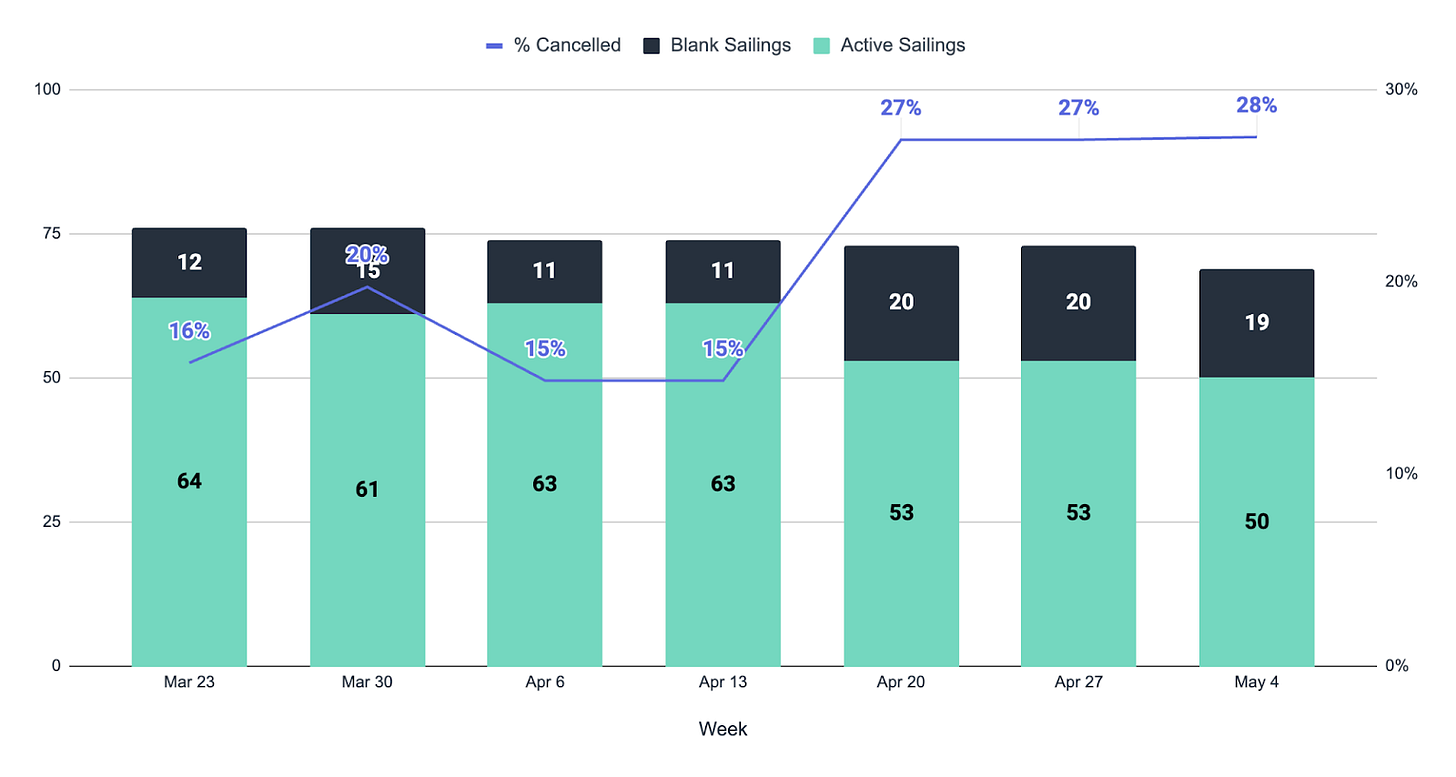

What did importers do? They panicked. They rushed to bring in as much as possible before the tariffs kicked in. Ports were flooded in March as companies tried to beat the deadline. But after April 2, bookings for new shipments from China just collapsed. Petersen says bookings are down over 60%. Shipping lines have canceled 25% of their planned sailings.

That’s one in every four ships that were supposed to cross the Pacific now sitting idle or rerouted.

And this isn’t just a shipping problem. It’s an everything problem.

Fewer ships mean fewer containers. That means less work at ports, fewer truckloads to deliver, and fewer goods arriving at warehouses. The ripple effects are already hitting trucking companies, warehouse operators, and even manufacturers. Mack Trucks, a truck maker, has announced layoffs because demand is falling. Factories that rely on Chinese parts are scrambling—if they can’t get what they need, they can’t produce. Prices are going up. Deliveries are being delayed. And most of the pain hasn’t even hit yet.

Right now, stores still look fine. Why? Because businesses stocked up ahead of the tariffs. There’s inventory sitting on shelves and in warehouses. But that buffer won’t last. In the next few weeks, we’ll start to see the gaps—items going out of stock, fewer options, higher prices.

And there’s no easy fix.

If you can’t import from China, where do you go? Vietnam? India? Mexico? Some companies are trying. But China’s manufacturing scale is unmatched. It’s not just that they make a lot—it’s that they make everything. Toys, tools, batteries, cables, buttons, screws. Even if you shift final assembly elsewhere, many of the parts still come from China. You can’t just unplug from that overnight.

There’s also another problem brewing in the background: the bullwhip effect. Right now, everything’s frozen. But if the U.S. suddenly reverses course and lifts or reduces tariffs, all the orders that were canceled might come flooding back at once. The system isn’t ready for that.

Ships have been pulled off the route. Crews have been reassigned. If a surge happens, there won’t be enough capacity. Rates could explode. During the pandemic, container prices from China to the U.S. hit $20,000. Petersen says if this whiplash happens, we could see those kinds of insane rates again.

Meanwhile, some businesses are trying to switch to air freight to beat the delays. But that’s not a real solution. Air freight is expensive and can only handle a tiny fraction of global trade. Even shifting 1% of ocean cargo to air is enough to send prices over $10 per kilo, like we saw during COVID. We’re already seeing those rates climb now.

And all of this flows back to consumers.

This summer, if things don’t change, people could start noticing strange things. Not dramatic shortages like during COVID—but gaps. A certain model of a phone that’s suddenly not available. A toy your kid wants that’s out of stock. A weirdly expensive kitchen appliance.

Economically, the risks are massive. If trade keeps falling, the knock-on effects could be brutal. Petersen warns that if these tariffs stay, we could be looking at a $2 trillion hit to the U.S. economy, mass business closures, and millions of job losses. That might sound dramatic—but remember, this is someone who watches the flow of goods in real time. When he sees a 60% drop in container bookings, he’s not just sounding an alarm for fun.

The real tragedy here is that this didn’t need to happen. It’s policy-driven. A decision made in Washington is now rippling across the world and threatening to hurt the very people it claims to protect—businesses, workers, and consumers. It’s turned the most basic engine of global commerce—shipping—into collateral damage.

If the tariffs are reversed soon, we’ll still face chaos, but the system might recover. If they stay, we’re headed into a slow-moving crisis. And the ships won’t lie. When bookings drop, you know demand is gone. When ships don’t sail, you know products won’t show up. When that happens, everyone—from the dock to the warehouse to your local store—feels it.

Is dollar losing it’s shine?

See things have gotten a bit messy. One day there are tariffs, the next day they’re gone, and the day after that, a new version is back. We've covered this rollercoaster before on The Daily Brief. Every tweet, every press conference from Donald Trump flips the market's mood — and the bigger concern now is that all this uncertainty has started to shake something that once felt unshakable: the US dollar’s reputation.

And, people are starting to ask: Is the dollar still that safe haven?

And that's where Akash Prakash of Amansa Capital, steps in. He recently wrote in Business Standard and he made a sharp point that cuts through the confusion:

“The dollar can weaken and still remain the world's currency—don't confuse the two.”

That line’s important, and we’ll come back to it. But let’s first understand why the dollar is so central to everything.

Why the dollar is “The Currency”

Since the end of World War II, the US dollar has been the world’s reserve currency. That basically means: when countries want to save money, do trade, or protect themselves in a crisis, they prefer to hold and use dollars.

Why? Because:

The US has the biggest and most liquid financial markets.

US Treasury bonds (government debt) are considered one of the safest places to park money.

Most global trade — like oil, metals, semiconductors — still happens in dollars.

Almost 60% of all foreign exchange reserves i.e. basically, countries’ emergency money is held in dollars.

And thanks to this, the US enjoys what’s been called an “exorbitant privilege.” It can borrow money at cheaper rates. It can impose financial sanctions with more impact. It can fund massive deficits without crashing its currency.

So… what’s changed?

A few things are making people nervous now.

Akash Prakash points out that bond yields in the US are rising.

Normally, when there’s a crisis, investors rush to buy US bonds — pushing yields down. But recently, yields have been going up. That means people are not flooding into US bonds like they used to during uncertain times. It’s a red flag. A sign that trust in US financial leadership is weakening.

Why?

Because the US government has been spending aggressively, running huge deficits, and playing fast and loose with policy. And if investors feel the US might become financially unstable — or that its politics are too chaotic — they’ll demand more returns to take the risk. That’s why yields go up.

Interestingly, gold recently hit all time highs maybe one reason could be all this uncertainty.

What about de-dollarisation?

This brings us to a much-hyped topic: de-dollarisation — the idea that countries are trying to reduce their reliance on the dollar.

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) has a brilliant article around this whole topic, and here’s the real picture.

Yes, there’s a trend where some BRICS countries are looking for alternatives to the dollar. But this is mostly happening in bilateral trade — like China and Russia using the yuan to settle oil trades.

Russia is the most aggressive here, but not by choice — it’s been cut off from the dollar system. China is cautiously increasing the yuan’s use in international trade, but it’s not trying to replace the dollar outright. It can’t — not until it loosens capital controls, allows free movement of money, and builds deeper financial markets. And as one of CFR’s expert put this:

“China does not have the intention or the capacity to dethrone the dollar.”

There’s also been talk of a shared BRICS currency, but again — it’s more of a geopolitical idea than an actual financial plan. There's no common central bank, no common bond market. It’s not realistic anytime soon.

India is not part of the “down with the dollar” club. In fact, External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar made it very clear just recently:

“I don’t think there’s any policy on our part to replace the dollar… The dollar as the reserve currency is the source of international economic stability. And right now, what we want in the world is more economic stability, not less.”

So… is the dollar falling?

In a way, yes. The value of the dollar has softened a bit in currency markets. But that’s normal. It doesn’t mean the dollar is collapsing or losing its global status.

What Akash Prakash is saying — and what people often miss — is that there’s a difference between:

The price of the dollar going down a bit…

…and the role of the dollar as the foundation of the global financial system.

One can change without the other.

India’s banking problems

India’s banking system is dealing with two big problems that seem connected but are actually separate issues. Economist Rajeswari Sengupta describes these clearly in a Moneycontrol article:

“India’s banking sector faces two interlinked but separate challenges: persistent liquidity tightness and a structural funding shortfall.”

Basically, banks have two main types of problems. First, they don’t always have enough cash to cover short-term demands—like when lots of people withdraw money all at once. Second, they’re struggling with getting enough stable, long-term money to give out loans safely.

Let’s me first clear up what each of these clearly mean.

First, what's liquidity?

Liquidity means having enough cash on hand, or stuff you can quickly sell for cash, to meet your short-term needs. Think about it like this: even a healthy bank can run into trouble if everyone decides to withdraw their money at the same time, or if businesses suddenly need to use their credit lines. This kind of short-term cash crunch is what liquidity is about.

This happens pretty regularly, especially around the end of financial quarters or years when people and businesses withdraw lots of money to pay taxes or settle bills. She points this out clearly:

“February and March, which mark the financial year-end, routinely see tight liquidity due to tax outflows and year-end funding needs.”

But things got extra tough in early 2025. The RBI had to step in and stabilize the rupee’s value against the dollar by selling dollars and buying rupees. This action took rupees out of the banks, creating an unusually big liquidity shortage of nearly ₹3 trillion—the biggest crunch in recent years.

How the RBI fixed short-term liquidity

To help banks quickly, the RBI put a lot of money into the banking system. Sengupta mentions, “the RBI injected more than ₹8 trillion into the system using various tools – variable rate repo auctions, open market purchases of government securities, and rupee-dollar swaps.”

Let's break these down:

Repo auctions: This is when the RBI gives short-term loans to banks using government bonds as collateral. Banks later pay this back, but it helps immediately.

Open Market Operations (OMOs): Here, the RBI directly buys government bonds from banks. This gives banks immediate cash. Usually, OMOs involve smaller amounts compared to repo auctions.

Forex swaps: The RBI temporarily trades rupees for dollars with banks, injecting rupees directly into the system.

These measures worked quickly. Banks went from severe shortages to comfortable liquidity. It wasn’t just about easing short-term pressure; it also ensured banks would actually lower loan interest rates when the RBI lowered its benchmark rates. Without enough liquidity, banks wouldn’t pass on these lower rates because they'd be desperate to attract cash.

The bigger, long-term funding issue

Liquidity solves immediate problems, but banks need stable, long-term funds for their core business—lending. Deposits from regular people like you and me are the main source of these funds. When we leave our money in fixed deposits or savings accounts, banks use that money for long-term loans like car loans or home loans.

Sengupta highlights this clearly:

“the core issue is long-term availability of stable funding — mainly through deposits or long-term bond issuance.”

Banks need reliable, long-term funding to grow safely. Without enough of it, they either lend less (which hurts economic growth) or use riskier short-term funds (which is unstable).

Why aren't savings flowing into banks?

Deposits from households, traditionally India's main source of bank funding, have not been growing well. Sengupta explains why clearly: “Stagnant nominal wage growth, persistently high food inflation, and rising household debt have together reduced financial savings.” In simple terms, people aren’t saving as much money as before, partly because incomes aren’t rising fast enough and everyday expenses like food have become more expensive. This means less money is available to banks as deposits.

This isn’t something the RBI can easily fix. They can change interest rates or manage liquidity, but they can’t directly make people save more money. Sengupta stresses this, saying this issue is “beyond the RBI’s reach.”

What else can banks do?

If banks can’t rely solely on household deposits, they have some other options:

Long-term bonds: Banks can issue long-term bonds to investors, locking in funds for several years.

Securitization: Banks can package loans into securities and sell them. This frees up money quickly.

Corporate bonds: Encouraging more businesses to issue bonds directly to investors can reduce banks’ burden to provide all the long-term loans.

These alternatives help but aren't perfect. Bonds usually cost more than deposits, which might reduce bank profits. Securitization only works well when investors trust the loans packaged into securities.

Structural solutions are needed. Sengupta's analysis makes one thing very clear: India’s banking sector is changing structurally. The era of easy, abundant bank deposits due to strong economic growth might be ending because of changes in household finances and more financial options for people.

While the RBI will continue to handle short-term issues with liquidity injections, the deeper, long-term funding problem needs bigger solutions. Simply put, addressing structural funding shortfalls requires broader reforms that go beyond monetary policy.

Please let us know what you think of this episode 🙂

Welcome back Krishna