Who said what About Fund Managers, Small-Cap Frenzy, Deregulation & Europe’s Crisis

Hey everyone, welcome to another episode of Who Said What! This is the show where we take interesting comments, headlines, and quotes that caught our attention and dig into the stories behind them You know how every week, there’s a bunch of headlines that grab everyone’s attention, and there’s so much hype around them? Well, in all that chaos, the nuance—the real story—often gets lost. So that’s the idea: to break things down.

People managing your money aren’t experienced enough?

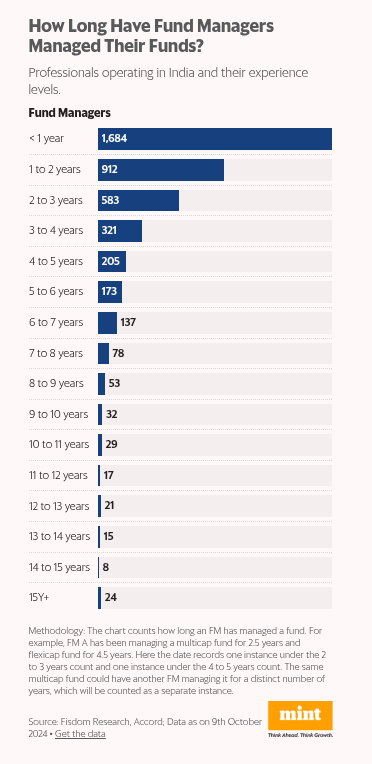

A video from Livemint made a bunch of people mad on Twitter. Before you say are you on Twitter all the time? No, not us but our boss—Bhuvan. Anyway in the video, journalist Neil Borate, cites research from one of their previous articles around fund managers. The article basically says that only a tiny fraction of managers show a 15+ year stint on the same scheme.

At first glance, that’s alarming—most investors expect their fund manager to have navigated multiple bull and bear cycles, such as the 2008 crash or the first COVID lockdown. The column cites familiar veterans like S. Naren (ICICI) and Prashant Jain (formerly with HDFC MF), describing them as among the few who have stayed with a single fund for such a long stretch.

However, there’s one tiny nuance in this: the dataset counts each “manager–scheme” combo separately. If a single manager oversees two different equity funds for different durations, that individual appears twice—once for each scheme.

It seems like this didn’t sit right with a bunch of people from the industry. Radhika Gupta, CEO of Edelweiss AMC, called the conclusion “strange,” pointing out that many managers have 25+ years of industry experience but might have joined a new fund or AMC only recently.

Another tweet we saw said that even an industry stalwart like S. Naren appears “inexperienced” if you only consider his tenure managing each specific scheme.

Pavitra Parekh of Mirae Asset likened it to an experienced surgeon switching hospitals—no one would suggest their expertise vanishes overnight.

There’s another crucial nuance the Mint column doesn’t fully explore: in some fund categories, the manager’s role is less critical. Index funds and certain debt funds, for instance, are driven more by a set process than by active market calls. An index fund manager’s main task is to track the benchmark (like the Nifty or Sensex) and keep tracking error low. In short-term debt funds, especially those focused on overnight or liquid instruments, the manager has limited discretion; much of the return depends on adhering to guidelines around credit quality and liquidity.

Hence, while the Mint piece warns that shorter scheme-specific tenures might mean fewer experiences with market crises, critics note that for passive or formula-driven funds, the “scheme history” metric might not be as relevant. You don’t necessarily need a “star” manager in an index fund; you just want someone who reliably replicates the index.

How many schemes are too many schemes?

Neil from LiveMint posted an infographic that shows how some of India’s biggest AMCs have piled up dozens of mutual fund schemes, often leaving investors with overlapping portfolios and unnecessary fees.

According to Neil, the industry’s constant stream of new funds can nudge you into “owning the entire market”—but at a higher cost and with more taxes. Of course, after this people from the finance industry joined in on this. Nilesh Shah, MD at Kotak AMC, says the sheer number of choices isn’t really the issue. In his words, it’s like having tons of restaurants around: you don’t need to shut them all down or stop eating out altogether—you just need to find a “good dietitian” who’ll help you pick what’s right for you.

Meanwhile, Deepak Shenoy (founder of Capital Mind) pointed out that new launches can mean bigger distributor commissions.

What about the bigger picture of fund categories themselves? Back in 2017–18, SEBI introduced new guidelines requiring mutual funds to clean up their offerings and clearly define each fund’s category and objectives. The idea was that standardizing categories—large-cap, mid-cap, multi-cap, and so on—would reduce confusion for retail investors.

But Amit Kumar believes that, despite the 2018 reclassification, “the scheme names and intended objectives have started overlapping big time now” such that “no layperson can make any sense of them”. Funds labeled “business cycle,” “cyclical,” or “discovery” might have distinct names but often end up in the same investing space.

In other words, marketing spin seems to be overtaking the actual differences in strategy or portfolio composition. According to him, a “full revamp” of mutual fund categories by SEBI and AMFI is needed—and, in his view, these major overhauls often happen “only in a bear market” when the flaws in the system become too obvious to ignore

At the end of the day, it raises a big question about whether we genuinely need so many schemes—or if it’s mostly about marketing. What do you think—do we have too many schemes?

Large caps are valued the same as small caps?

Last week, we broke down what Aswath Damodaran and Sankaran Naren had to say about valuations and let’s just say—opinions were flying. Damodaran called India the most expensive market in the world, and Naren went full 2008 crisis mode, warning investors about small caps.

But this week, we came across something just as interesting. A tweet from Samit Vartak, the Chief Investment Officer at SageOne Investment, got our attention. Samit for context is someone who has long championed mid and small-cap investing.

In his post, Samit dissected how valuations for different market segments—large caps, mid caps, and small caps—can often be misleading. He pointed out that public sector undertakings (PSUs) and banks generally trade at lower price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios, and because these stocks make up a larger chunk of the large-cap universe, they distort the weighted average P/E multiple.

His key argument? Using broad P/E ratios to compare large, mid, and small caps is like comparing apples to oranges.

Here’s where things get interesting. Samit argues that in large caps, PSUs contribute 33% of total profits, while in small caps, their contribution is only 9%. This means that the overall weighted P/E for large caps appears lower not necessarily because they’re cheap, but because of these lower-multiple stocks.

His solution? Look at the median P/E, not the weighted average. When you remove PSUs and banks from the equation, the true valuation picture emerges:

The weighted average P/E of the large-cap universe is 21.6x, compared to 29.9x for small caps.

But if you strip out PSUs and private banks, the median P/E for large caps jumps to 42x, while small caps drop to 33.3x.

This flips the entire valuation debate on its head. The popular narrative right now is that small caps are wildly expensive, but if you adjust for composition, they may not be as stretched as people think.

But That’s Just One Side of the Story

Samit didn’t stop there. In an interview with ET Now, he gave a more nuanced take on mid and small caps. Here’s where it gets juicy.

First, he acknowledged the excesses of the past couple of years. He pointed out that during the bull run, investors were throwing money into small caps without doing any real due diligence—buying first and researching later. This created an environment where stocks were rallying purely on momentum, not fundamentals.

He specifically called out pre-IPO and IPO deals where companies were selling a dream—projecting 4-5x revenue growth in just a few years. Samit bluntly said, "It’s impossible for thousands of companies to grow at that pace." And yet, many investors were buying into these stories without questioning them.

So, is the small and midcap correction over? Not entirely.

He thinks there’s still a lot of “froth” in the market, especially among companies that benefited from speculative excesses. But for good stock pickers, this correction is actually creating opportunities.

His biggest takeaway? If you’re investing in small and midcaps, don’t just go by market cap. Bet on business quality, promoter integrity, and market leadership. The days of blindly buying an index or a theme are over.

What’s Happening in the Markets Right Now?

The markets have come off their peaks, and if you look at the numbers, the drawdown is significant.

Nifty 50 is down around 9%

Midcaps? Even deeper, with NIFTY Midcap 150 falling close to 15%

Small caps have been hit the hardest, with NIFTY Smallcap 250 down 19%

As of 21st Feb.

Deepak Shenoy’s Perspective

Another interesting take came from Deepak Shenoy, the founder of Capitalmind. He acknowledged the pain in the markets but had a slightly more balanced view.

In his tweet, he said:

"Markets are [going to] be rough a little, and while I also think the fall seems stretched, there is no predicting when it will stop. The corrections now are between 10% and 25%, and it's been slow. Will take time to recover, but there's more to buy now than in September."

This is a critical point—while people are panicking, corrections create opportunities. Shenoy isn’t dismissing the fall, but he’s also saying that if you have a long-term view, there’s a lot more value on the table today than just a few months ago.

Now, where does all of this leave us? One thing that we took away last week and again this time is valuations alone don’t say everything. Valuation numbers mean nothing unless you know what’s behind them, if you know where to look, there’s a lot to buy. But the latter is the hard part, isn’t it?

The push for deregulation

Pranay Kotasthane—who writes about public policy and is deputy director of the Takshashila Institution—wrote about deregulation recently.

His piece—which is mostly written in Hindi—reacts to the bold statements on deregulation in the Economic Survey’s Preface, where the Chief Economic Advisor boldly states that the government should “stop micromanaging economic activity” and “get out of the way” of entrepreneurs.

Pranay, who wrote most the piece in Hindi, includes this striking quote from the Survey’s Preface:

“…सरकारों का सबसे बड़ा योगदान बिज़नेस के लिए यही हो सकता है कि वो उनके रास्ते से हट जाए… जब तक सरकारें सोच-समझकर रेग्युलेशन नहीं करेंगी और कठोर नियमों का तुरंत अंत नहीं करेंगी, तब तक उद्यमी इनोवेशन और प्रतिस्पर्धा पर ध्यान नहीं दे पाएंगे... सरकार को व्यापारियों और उद्यमियों पर विश्वास करना सीखना होगा…”

In English, that translates to:

“The biggest contribution governments can make to businesses is simply to get out of their way. If governments do not regulate with caution and immediately end burdensome rules, entrepreneurs will never be able to focus on innovation or competition. The government must learn to trust entrepreneurs and businesses.”

Pranay points out that this honesty about “cutting red tape” is refreshing—and long overdue. To illustrate why reducing regulatory barriers matters so much, he shares one of India’s best-known examples: the Maruti story. While many believe Maruti thrived because India protected it behind heavy import barriers, Pranay highlights a more nuanced truth.

Drawing on Monty Singh Ahluwalia’s book Backstage: The Story Behind India’s High-Growth Years, he shows that Maruti actually took off once it enjoyed exceptions to the usual licensing chaos. Put simply, the government allowed foreign collaboration, eased production limits, and relaxed certain license hurdles—giving Maruti room to scale up and succeed.

Or, as Pranay says in Hindi:

“दरअसल भारत की कई प्रचलित सफलताएँ भी deregulation का ही नतीजा हैं, लेकिन हम इस बात को अक्सर नज़रअंदाज़ कर देते हैं… अगर आप किसी को पूछें कि मारुति क्यों सफल हुई… असल में मारुति की सफलता इसीलिए हुई क्योंकि उसे सही समय पर ढील दी गई—यानी Deregulation!”

Translated:

“In reality, many of India’s major success stories are outcomes of deregulation, although we often overlook that fact. For example, if you ask someone why Maruti succeeded, most people will say it’s because India kept foreign players out and supported a domestic brand. But the truth is, Maruti was successful precisely because it was granted more flexibility at the right time—i.e., deregulation!”

Pranay observes that once India extended that kind of deregulatory push beyond Maruti—especially during the broader economic reforms of the 1990s—scores of other industries began to flourish. This, he says, is exactly the point of the Economic Survey’s Preface. The Chief Economic Advisor argues that simplifying regulations (a) cuts costs for businesses, and (b) unleashes entrepreneurship by freeing people from “mind-boggling” compliance structures. According to the Preface:

“Lowering the cost of business through deregulation will make a significant contribution to accelerating economic growth and employment amidst unprecedented global challenges.”

But it’s not about having zero rules. The Survey particularly emphasizes smart, streamlined, risk-based regulation, where the government stands ready to address genuine risks but otherwise trusts businesses to get on with their work.

In a similar vein, Uday Kotak has also underscored the need for India to move from what he calls “micro-management” toward genuine growth and competition speaking at Kotak Institutional Equities' investor conference ‘

We are quoting from the report on what he spoke about:

In his view, India cannot afford protectionism; India has to take advantage of changing times and make Indian industry competitive than protective. The new world will give limited options to run large current account deficits. He emphasized the need for India to (1) improve productivity, (2) avoid excessive protectionism and (3) increase manufacturing as a percentage of GDP. He also highlighted the importance of execution in both macro- and microeconomic policies.

Kotak also highlights the importance of “execution in both macro- and microeconomic policies,” echoing the Chief Economic Advisor’s call to streamline red tape. In his view, trusting entrepreneurs and letting them innovate—while still guarding against genuine risks—has played a significant role in India’s past successes and will be vital for sustaining growth in the coming decade.

Draghi's New "Whatever It Takes" Moment

In 2012, Mario Draghi uttered three words that would save the euro: "Whatever it takes."

As President of the European Central Bank, he promised to preserve the eurozone’s currency at all costs. The markets listened, and the crisis subsided.

Now, in 2025, Draghi has a new message for Europe, but this time it’s tinged with frustration: "Do something." Speaking to the European Parliament about his report on competitiveness, the former ECB President and Italian Prime Minister laid bare his exasperation with European inaction. “You say no to public debt, you say no to the single market, you say no to create the Capital Market Union… you can’t say no to everything,” he warned.

But what’s driving this urgent call to action? Draghi’s comprehensive speech reveals a Europe facing multiple existential challenges:

First, there’s the AI gap. Europe is falling behind, with 8 out of the top 10 large language models developed in the United States, and the remaining two in China. Every day of delay, as Draghi puts it, “the technology frontier is moving away from us.”

Then there’s the energy crisis. European power prices are two to three times higher than in the United States.

During a recent cold spell in December, when solar and wind power generation dropped to near zero, German power prices skyrocketed to ten times their yearly average. This isn’t just about keeping the lights on – it’s about maintaining European industrial competitiveness.

Yet perhaps most striking is Draghi’s revelation about Europe’s internal market. While the EU’s market is similar in size to the United States, internal barriers are equivalent to a tariff of 44% for manufacturing and a staggering 110% for services. As Draghi notes, “We are often our own worst enemy.”

The irony? Europe has the savings – sending over 300 billion euros annually overseas because investment opportunities are lacking at home. It has a market size comparable to that of the US. It even has an industrial base – employing 30 million people in manufacturing compared to 13 million in the US.

But if Europe’s economy needs a jolt, it is Germany’s troubles that are sounding the loudest alarm. Europe’s industrial powerhouse has lost almost a quarter of a million manufacturing jobs since the start of the Covid pandemic, with industries from automotive to chemicals warning of further cuts

High energy costs, consumer malaise, and competition from China are threatening what was once the bedrock of European growth.

German politicians, bracing for elections, have begun to speak openly of “deindustrialization” if energy costs remain so high and investments continue moving abroad. For Europe’s biggest economy to sputter now, amid all the other crises, only deepens Draghi’s sense of urgency.

Meanwhile, Europe’s security dilemma is taking on new dimensions. Twelve years ago, Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech saved the euro through the power of conviction. Today, his “do something” plea reveals a different kind of crisis – not one of immediate market panic, but of gradual decline in the face of technological and geopolitical change.

Another critical vulnerability Draghi highlights is Europe’s fragmented defense industry. Despite being the world’s third-largest defense spender collectively, Europe’s national defense systems aren’t interoperable or standardized. As Draghi puts it, “This is one of the many examples where the European Union is less than the sum of its parts.”

Yet there’s a deeper issue: trust between allies. An FT editorial recently asked, “Is the US still an ally? Has it become an adversary?” Some European officials worry that Washington might turn inward or make separate deals with Russia, leaving Europe “dangerously exposed.” Meanwhile, a well-known columnist warns that Europeans must cut back their “dangerous dependence” on an America that might no longer be reliable. In other words, Europe’s economic problems are closely tied to its geopolitical situation—especially if it has to handle more of its own defense while the US commitment wavers.

The scale of the challenge is massive. Draghi estimates Europe needs 750-800 billion euros annually in investment. While the European Commission has proposed streamlining EU financing instruments, there are no plans for new EU funds. Instead, success depends on member states being willing to use their fiscal space within a European framework.

Perhaps most tellingly, Draghi warns that if recent statements are any indication, Europe may be “left largely alone to guarantee security in Ukraine and in Europe itself.” It’s a sobering reminder that Germany’s industrial strains, high energy costs, and Europe’s fractured defense structures all converge in a moment when the US might not be the reliable partner it once was.

The question now is: Will Europe listen this time?

🌱 Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side project we started, and it's starting to become fascinating in a weird and wonderful way. We write about whatever fascinates us on a given day that doesn't make it into the Daily Brief.

So far, we've written about a whole range of odd, weird, and fascinating topics, ranging from India's state capacity, bathroom singing, protein, Russian Gulags, and economic development to whether AI will kill us all. Please do check it out; you'll find some of the most oddly fascinating rabbit holes to go down.

Please let us know what you think of this episode 🙂

Very well written.

How about a dash of company specific news too? You wrote about Maruti thriving in india. But why not go down the rabbit hole of why years of tariff protection has made all these homegrown car companies lazy and entitled?-- none of our storied Indian companies like Maruti or Mahindra or even Hero for that matter has any sizeable exports.

Throw them abroad with the wolves of China and US and they'll get slaughtered. Why? Years of tariff protection and huge homegrown market dulls our need for cutting edge innovation. It's the same story with Bollywood cinema.

Think about it--even Mahindra Thar didn't really make a splash in the world. Meanwhile Mr Mahindra twirls his moustache and basks in orgies of self congratulation.

Only one company is attempting to take on the world--Eicher motors. Royal enfield and its glittering array of new launches are proving to be a hit abroad.

Perhaps it has more to do with its promoter, Sidd Lal who speaks less and is more focussed on innovation than patting his back.