Who said what about EMS sector hype, reality of EVs, Trump's $200 billion deal and more

Have you ever wondered what industry leaders or policymakers really mean when they say something? Their words often carry hidden layers of meaning, hinting at things that aren’t immediately obvious. That’s exactly what we aim to uncover here on "Who Said What."

Today, we’ve got 4 interesting comments to share with you.

Prefer video? you can watch it here:

S Naren's view on EMS

S. Naren is a big name in the mutual fund industry. He’s the Chief Investment Officer (CIO) at ICICI Prudential Fund and manages over ₹2 lakh crore. He’s one of the most respected voices in the investing world, and when he speaks, people pay attention.

Recently, he said this:

“If you look at EMS today, it is just like 2007 infra. Someone signs an agreement today for the next 10 years, profits are already priced into the stock on that day. That’s the way the sector behaves.”

We’ve been researching the Electronics Manufacturing Services (EMS) sector for The Daily Brief, our daily show, and have some thoughts on this comparison. Let’s break it down, and you tell us if it makes sense.

Before exploring the EMS sector, it's important to understand why he drew a comparison between today's EMS landscape and India's infrastructure sector in 2007. At that time, India was experiencing rapid economic growth, with the economy expanding at nearly 9% annually. There was a widespread consensus that sustaining this growth required significant improvements in infrastructure. A thriving economy simply couldn't rely on potholed roads, erratic power supply, and overcrowded airports.

The government announced massive projects like the National Highway Development Project, Bharat Nirman for rural infrastructure, and others under the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) model. Suddenly, infrastructure stocks became the market’s favorite.

Companies like GMR Infra, GVK, and Reliance Infra aggressively bid for these huge projects. To win contracts, they underestimated costs and overpromised timelines. Banks, seeing infrastructure as a “safe” bet, lent billions. Foreign investors (FIIs) poured money into these stocks, driving prices up by 500%-1,000% in just a few years.

At the time, if you questioned the high valuations, you were laughed at. But here’s the thing: building infrastructure in India isn’t easy. Land acquisition delays, rising costs, and growing debt started piling up.

Then came the 2008 global financial crisis. Foreign investors pulled out, banks tightened their lending, the rupee crashed, and infrastructure companies, drowning in dollar-denominated debt, couldn’t repay their loans.

By 2012, the dream was over. Highways and power plants were left unfinished, companies defaulted, and banks were stuck with huge bad loans. The scale of the collapse? The Nifty Infrastructure Index, which peaked in 2008, gave almost 0% returns for more than a decade, until 2021.

Now, let’s talk about the EMS sector. To give some context, most companies in this space in India are essentially assemblers. They focus on designing, producing, assembling, and repairing electronic products for other companies, like smartphones, laptops, and telecom equipment.

A few players are starting to invest in higher-value areas like chip manufacturing, but this is still at a very early stage. For now, most Indian EMS companies are still far from becoming full-fledged manufacturers and have a long way to go before they can compete in the more advanced parts of the global electronics supply chain.

That said, the EMS sector is being hyped as India’s next big growth story—and for good reason.

India is positioning itself as a global hub for electronics manufacturing, backed by government initiatives like the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, which offers financial rewards to companies scaling up domestic production.

Big names like Apple and Foxconn are expanding their production in India, while local players like Dixon Technologies and Kaynes Technology are increasing their capacity. Global companies are also looking to diversify their supply chains away from China due to rising tensions between China and the US. This trend could pick up even more steam next year if Trump returns to the presidency, likely escalating geopolitical rivalries further.

On paper, it all looks like the perfect setup for success: a fast-growing electronics market, strong government support, and global supply chains moving away from China under the "China+1" strategy.

But here’s where things get complicated. Despite its growth potential, the EMS business is incredibly fragile. Profit margins in this sector are razor-thin—operating profit margins are often less than 10%.

Most EMS companies rely on massive volumes to make money, which means their entire business model depends on perfect execution. Even a small problem—like a delay in scaling production, higher input costs, or losing a government incentive—can wipe out those thin profit margins in no time.

Then there’s the issue of valuations. EMS stocks in India are currently trading at price-to-earnings (P/E) multiples of 70x to 100x earnings.

The problem with such high valuations is that they don’t leave any room for mistakes. If the expected growth doesn’t happen—or if profit margins take a hit—these stocks could face a sharp correction.

This is exactly what Naren was talking about when he said, “Someone signs an agreement today for the next 10 years, profits are already priced into the stock on that day.”

Trump's $200B deal

Masayoshi Son, the CEO of SoftBank—one of the biggest tech investors in the world—recently pledged to invest $100 billion in the U.S. since Trump came to power.

But the surprising part isn’t the $100 billion itself. These kinds of announcements are often just for show. CEOs and companies love to make big promises about spending money they may not have on things they’re not even sure they want to do. This feels no different.

What stood out, though, was the press conference where Trump tried to strong-arm Son into doubling his commitment from $100 billion to $200 billion. He treated Son like an old buddy from the playground, cracking jokes and acting overly familiar. Honestly, the video is hilarious—you’ve got to watch it.

But here’s where things take a more serious turn. Lately, we’ve noticed something strange, and it’s not in a good way. Silicon Valley’s top leaders and industry giants have been going out of their way to stay on Trump’s good side. From Jeff Bezos and Ted Sarandos of Netflix to Mark Zuckerberg, they’ve all been lining up, trying to win his favor. The unspoken goal? To avoid becoming a target for Trump’s public attacks.

And speaking of Trump, his second presidency could be one of the first where billionaires essentially run the show. A recent article in The New York Times highlighted how people like Elon Musk, Marc Andreessen, and Larry Ellison are playing massive roles—not just in influencing policies but in helping pick cabinet members.

Billionaires have always had some sway in politics, but this time, they’re not even pretending to stay behind the scenes.

TVS's Chairman Emeritus says EVs are overhyped

Venu Srinivasan, Chairman Emeritus of TVS Motor Company, didn’t hold back in a recent interview with NDTV Profit. Talking about electric vehicles (EVs), he said, “EVs were hyped up as if it was a panacea and it would solve all problems.”

That’s not something you’d expect to hear from someone leading one of the country’s largest two-wheeler EV companies. But there’s more to it, as always. Srinivasan wasn’t dismissing EVs entirely. Instead, he was pointing out some hard truths that often get overlooked in all the excitement.

One of the biggest issues he raised was the lack of proper charging infrastructure.

While charging two-wheelers is relatively easy, it’s a different story when it comes to cars. “In the case of two-wheelers, you can charge at home overnight. The usage is about 30 kilometers a day, so there’s no range anxiety,” he explained.

This works because two-wheelers are mostly used for short, predictable commutes. But for cars? “In the case of a car, it is very difficult to charge up from the plug point in your house. You need specific charging stations, which most apartments don’t have, and there’s no public infrastructure available,” he pointed out.

And he’s right. India currently has about 12,000 public charging stations, which isn’t nearly enough to support widespread EV adoption. Charging a car is far more complicated than charging a two-wheeler, and without reliable public infrastructure, this remains a major hurdle.

Srinivasan also made it clear that this isn’t just an issue for India—it’s a global problem. “Billions and billions of dollars were spent on batteries and EV factories, and now they're finding that all the companies are slowing down,” he said.

He’s referring to automakers like Ford, General Motors, and Volkswagen, who have recently scaled back their EV plans. Why? Because demand hasn’t grown as quickly as expected, battery costs are still high, and profits remain elusive.

Srinivasan also criticized Europe’s aggressive timelines for phasing out internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles by 2030, calling them unrealistic. “European countries are giving up their competitive advantage in ICE engines and transmissions, which are far ahead of the rest of the world. They’re going to lose hundreds of thousands of jobs,” he warned

This isn’t just guesswork. A report by the European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA) estimates that over 500,000 jobs could be lost across the EU as the shift to EVs speeds up. For countries like Germany, where ICE production is a cornerstone of the economy, this could be devastating.

In India, the EV story is a mixed bag of progress and challenges. Two-wheelers are leading the way. Electric scooters are affordable, practical, and easy to charge at home, making them a natural choice for daily city commutes.

But the outlook for cars is less encouraging. The lack of charging infrastructure is a major hurdle. Add to that India’s reliance on imported materials like lithium and cobalt, which makes the industry vulnerable to supply chain disruptions. On the other hand, China’s vertically integrated EV supply chain gives it a huge edge in both cost and scale.

Srinivasan isn’t saying EVs are the wrong path—he’s saying we need to take a smarter, more phased approach.

“You have to have a progression. Start with CNG, which is already a cleaner fuel. Then move to hybrids, and finally to electric,” he suggested.

This step-by-step plan makes a lot of sense. Hybrid vehicles, for instance, can help reduce emissions without requiring a massive overhaul of existing infrastructure. CNG, which is already widely available in India, provides a cleaner and more accessible alternative to petrol and diesel.

Srinivasan summed it up well: “It’s not a sprint; it’s a marathon.”

Are we headed for another recession?

Ritesh Jain, the founder of Pine Tree Macro, always shares fascinating insights about global trends. Recently, he talked about the "disinversion" of the yield curve, which got us curious about what the research says about its predictive power.

But first, let’s break it down—what does all of this even mean?

Let’s start with the basics. When the government needs money, they borrow it by issuing bonds. Think of a bond as an IOU—you lend the government money, and they promise to pay you interest (called the yield) and return your money after a set period.

Just like you’d expect a higher interest rate for locking your money in a 5-year fixed deposit compared to a 3-month one, longer-term government bonds usually offer higher yields than shorter-term ones.

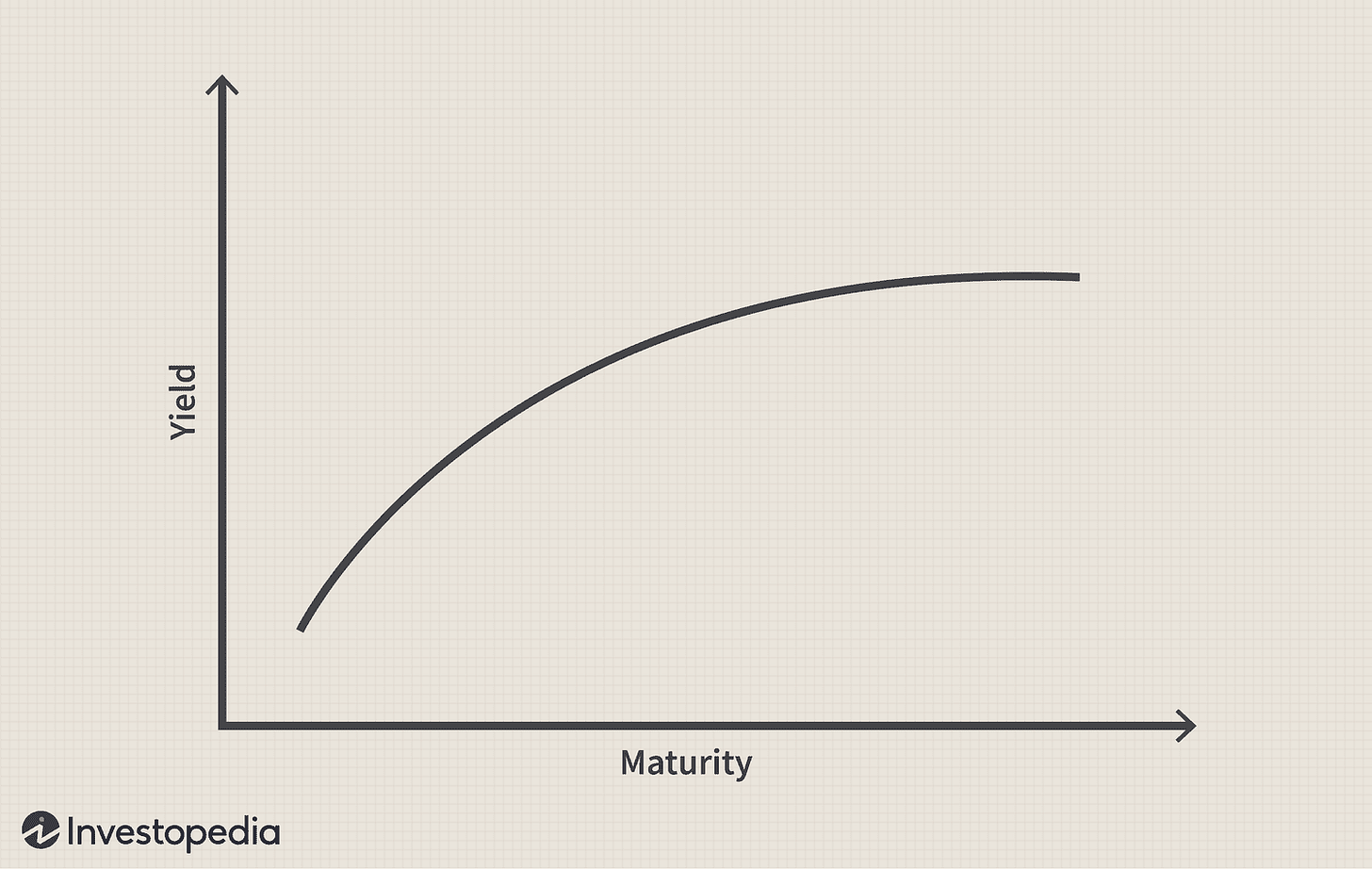

When you plot these yields on a graph—with time on the horizontal axis and interest rates on the vertical—you get something called the "yield curve."

Normally, the yield curve slopes upward because longer-term bonds pay more than short-term ones. But sometimes, this flips—short-term bonds end up paying more than long-term ones. That’s called an "inversion."

Why does this happen?

An inversion typically occurs when investors think tough times are coming. For example, if they expect the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates in the future to tackle an economic slowdown, they rush to lock in the current higher rates on longer-term bonds. This surge in demand pushes long-term yields down, sometimes below short-term rates.

Think of it as investors voting with their money—they’re betting that rates will drop in the future because the economy will weaken.

When the curve shifts back to its normal upward slope, it’s called "disinversion."

We’ve just come out of the longest yield curve inversion in history—779 days. What does this mean for the economy? Let’s dive into what the research tells us.

A study looking at yield curves across nine countries found that while they used to be reliable indicators of economic growth, their predictive power has weakened in recent years. Interestingly, European yield curves have remained more reliable than others. In Japan, however, the yield curve completely lost its predictive power when interest rates hit zero—a valuable lesson for today’s low-rate environment.

Larry Swedroe, a well-known expert, offers another perspective. He analyzed data from five major developed nations and found that stock returns after inversions were mixed. In the U.S., market returns were higher 66% of the time one year after an inversion but only 33% of the time three years later. When looking at all the countries studied, returns were higher 86% of the time after one year and 71% after three years. This suggests that while inversions may signal recessions, they’re not reliable for timing the stock market.

As for disinversion, history shows that 7 out of 8 times since 1965, it was followed by a recession within about six months. However, HSBC points out that there were exceptions in 1982 and 1998 when disinversions didn’t lead to recessions. They argue that disinversion doesn’t increase economic risk—it simply reflects market expectations of faster rate cuts.

HSBC suggests paying more attention to actual economic data rather than yield curves. They highlight today’s unique conditions: households and companies reducing debt, strong government investment programs, and resilient service industries despite weakness in manufacturing.

The takeaway is clear: while yield curves have historically been helpful in signaling economic shifts, especially in Europe, their predictive power depends on the country and the time period. The study, Swedroe’s analysis, and HSBC’s recent insights all point to the same conclusion—no single indicator, not even yield curves, can reliably predict economic turns.

As Swedroe puts it, if you hear about a market signal on TV or in the news, it’s probably too late to act on it. Instead of trying to time markets based on yield curves, investors would do better to focus on broader economic fundamentals and stick to a well-planned, long-term investment strategy.

That’s it for this edition, do let us know what you think in the comments and share with your friends to make them smarter as well.

Loved it