Who said What About diamond prices, Indian startups, SBI deposits, and India's steel imports | #4

Happy New Year, everyone! It’s been two weeks since our last episode. And we know by now you might have even forgotten the existence of this show but Krishna, the host, has to show that he did some work during the appraisals so he’s back with another edition of Who said what.

For those of you reading it for the first time, welcome! This is the show where he takes the most interesting quotes from leaders, policymakers, and industry giants, and peel back the layers to uncover what’s really being said—and, more importantly, what’s not.

Today we have 4 interesting things to share with you.

Prefer video? you can watch it here:

22 years of no returns

I came across this chart from LiveMint, and it immediately caught my eye.

It shows 22 years of zero returns for diamonds. Let that sink in—22 years. Over two decades, diamonds as an investment have basically gone nowhere. And yet, for most of that time, we’ve been told by marketing campaigns, hello, De Beers, that diamonds are the ultimate luxury, the pinnacle of value, something that’s “forever.”

So, what went wrong?

Let’s rewind. De Beers practically built the modern diamond industry with its genius marketing. “A Diamond Is Forever” wasn’t just a tagline—it was a way to convince people that diamonds were rare, precious, and a must-have for every engagement ring. And for a while, it worked. But here’s the thing about diamonds: unlike gold, which has universal liquidity, diamonds don’t have a reliable resale market.

And now, lab-grown diamonds have entered the scene and flipped everything upside down. We have written about this a bunch of times on The Daily Brief.

These diamonds are identical to natural ones in every way—chemical structure, physical appearance, everything. But they cost a fraction of the price. For buyers, it’s a no-brainer. Why spend ₹3–4 lakh on a natural diamond when you can get a lab-grown one for ₹50,000? Add to that the fact that lab-grown diamonds are marketed as “sustainable” and “conflict-free,” and you start to see why they’re becoming so popular, especially with younger buyers.

This shift to LGDs is hitting traditional players hard. Le us take the example of DeBeers again because they had to do something they had never done before— CUT PRICES. They’ve been forced to cut diamond prices by up to 15% this year—a huge deal for a company that usually tries to keep prices steady at all costs. They’re also stockpiling rough diamonds—$2 billion worth, their largest inventory since 2008—hoping demand will bounce back

In India, this segment is growing at 15–20% annually, with companies like Trent launching their own LGD brand POME. For Indian buyers, these diamonds are making luxury more accessible than ever before.

What's up with the Indian startup ecosystem?

“I was coerced and threatened… I had just 24 hours to agree to sell my shares and resign.” That’s what Amarendra Sahu, the founder of NestAway, told investigators, pointing fingers squarely at some of the biggest names in venture capital—Tiger Global, Chiratae Ventures, and Goldman Sachs. Sahu, who co-founded NestAway in 2015, had seen his company once valued at ₹1,800 crore, sell for a measly ₹90 crore in 2023.

And now, he’s accusing his investors of forgery, intimidation, and reneging on promises that they made to him as the company unraveled.

But we want to take a step back and unpack this slowly. You see this story isn’t just about NestAway or one disappointed founder. This is a story of the golden days of sky-high valuations, the lack of oversight during the funding frenzy of the COVID era, and the fallout that we’re still seeing now.

NestAway, once a promising rental housing startup backed by big names like Tiger Global and Goldman Sachs, seemed to tick all the right boxes. By 2019, it was a leader in the space, valued at ₹1,800 crore. But cracks soon appeared—competition grew, service quality dipped, and the pandemic crushed urban rental demand. By 2023, the company was sold to Aurum PropTech for just ₹90 crore. The founder, Amarendra Sahu alleges that investors forged his signature, coerced him into stepping down, and reneged on a promised ₹11.72 crore payout.

NestAway’s story isn’t an isolated case. It’s part of a larger pattern of turmoil in India’s startup ecosystem, especially after the COVID-era funding boom.

Take Zilingo. Once a billion-dollar unicorn revolutionizing the fashion supply chain, it raised over $300 million from marquee investors like Sequoia Capital and Temasek. But by 2022, things fell apart. CEO Ankiti Bose was suspended over alleged financial irregularities, and the company eventually liquidated. Bose has denied wrongdoing, claiming she was targeted, but Zilingo's collapse left behind a trail of lost jobs and questions about governance.

Then there’s GoMechanic. Positioned as a disruptor in the car servicing market, it had raised money from VCs like Sequoia Capital and Tiger Global. But then the founder admitted to inflating revenue numbers. An audit revealed fake invoices and fictitious garages, forcing investors to write off their stakes and pushing the company into insolvency.

What ties all these stories together? The funding boom of the pandemic years. When COVID struck, venture capital poured into startups like never before. With the world in lockdown, digital transformation became a buzzword, and every VC wanted to back “the next big thing.” Companies raised money at valuations that, in hindsight, seem absurd. Founders were flush with cash, and investors were falling over themselves to write bigger and bigger checks. There wasn’t much focus on governance or business fundamentals—growth was all that mattered.

For a while, this worked. Startups scaled rapidly, valuations soared, and everyone seemed to be winning. But then came the bust. As interest rates rose and global liquidity dried up, the tide went out, exposing who had been swimming naked. The once-sky-high valuations came crashing down. NestAway’s ₹1,800 crore valuation turned into ₹90 crore. Zilingo went from a unicorn to liquidation. GoMechanic’s “growth” was revealed to be smoke and mirrors.

The common thread in these stories is the lack of oversight—on both sides. Investors were so eager to chase growth that they overlooked governance. Founders, incentivized by ever-rising valuations, often took shortcuts, fudged numbers, or failed to build sustainable businesses. It was a perfect storm, and the fallout has been ugly.

SBI's Chairman on deposits

So, recently SBI’s chairman CS Setty made this comment on CNBC TV18

“Don’t See Deposit Cost Escalating, So Margins Will Be Stable.”

Here’s what he means when he says this.

See, earlier this year, we were in a situation where people like you and me were depositing money into banks at a slower pace than banks were giving out loans. This was a risky move—basically banks were stretching themselves thin, handing out more loans than they probably should have. Even the RBI Governor back then wasn’t thrilled about it.

We’ve talked about this before on The Daily Brief as well. But here’s the gist: the RBI got serious, urging banks to fix this imbalance. “Mobilizing more deposits” quickly became a top priority for every bank’s management team to-do list. They really didn’t have much of a choice.

When CS Setty took charge, he had to think fast and compete for deposits. At the time, the banking world was buzzing about how this so-called “war” for deposits was driving up costs for banks.

But Setty had a different take. He publicly stressed that deposit growth isn’t just about offering higher interest rates—it’s also about delivering better customer service and innovative products. He even talked about introducing a systematic investment plan (SIP)-style product for fixed deposits, which, if you think about it, already exists as recurring deposits (RDs). But hey, he wanted to rebrand it for Gen Z.

Now here’s where things get interesting. Over the past year, SBI’s deposit costs have seen the biggest spike among large Indian banks. Now, to be fair, these numbers reflect the strategies of Setty’s predecessor, not his own. But he clearly wants to change this. SBI already has one of the lowest deposit costs in the country, and he’s determined to keep it that way.

Fast forward to his latest interview, he is essentially “calling the top” on deposit rates. He believes deposit costs won’t go any higher from here. This is a big deal because rising deposit costs have been eating into banks’ profitability across the country. If deposit costs stabilize and loan rates hold steady, margins could actually improve, boosting profitability.

But let’s be honest—this isn’t exactly a groundbreaking prediction. Here’s why:

Rate cuts are coming. The repo rate—the rate at which the RBI lends to banks—is expected to drop soon. When this happens, the cost of money in the economy decreases. Here's why this matters: When repo rates go down, banks lower the interest rates on loans, making borrowing cheaper. At the same time, they also reduce the interest rates offered on deposits because they don’t need to compete as aggressively for funds anymore. For depositors, this means that high returns on fixed deposits or savings accounts become harder to find. But they’ll likely accept these lower returns because alternative investment options, like bonds or market-linked instruments, also offer reduced returns in a low-interest-rate environment. Essentially, when everything yields less, depositors adjust their expectations.

The deposit-credit gap is gone. Banks were under pressure by the RBI to attract more deposits because they were giving out more loans than they could support. Now that gap has closed, so there’s no urgency to keep raising deposit rates.

In short, Setty’s statement is less of a prediction and more of a confirmation of what’s already happening in the economy—if you’ve been paying close attention.

Tata steel has a problem with China

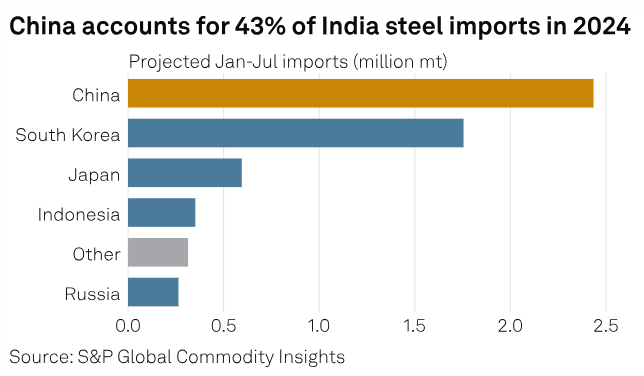

Tata Steel's CEO, T.V. Narendran, recently shared a big concern. He talked about how India’s growing steel demand—up by 8%—could be a massive opportunity for the country. But there’s a catch: China’s cheap steel is flooding markets everywhere, including India, and it’s starting to feel like a problem we can’t ignore. Narendran’s message was clear—India needs to take a stand, just like the US, Canada, and European nations have already done, to protect their local steel industries

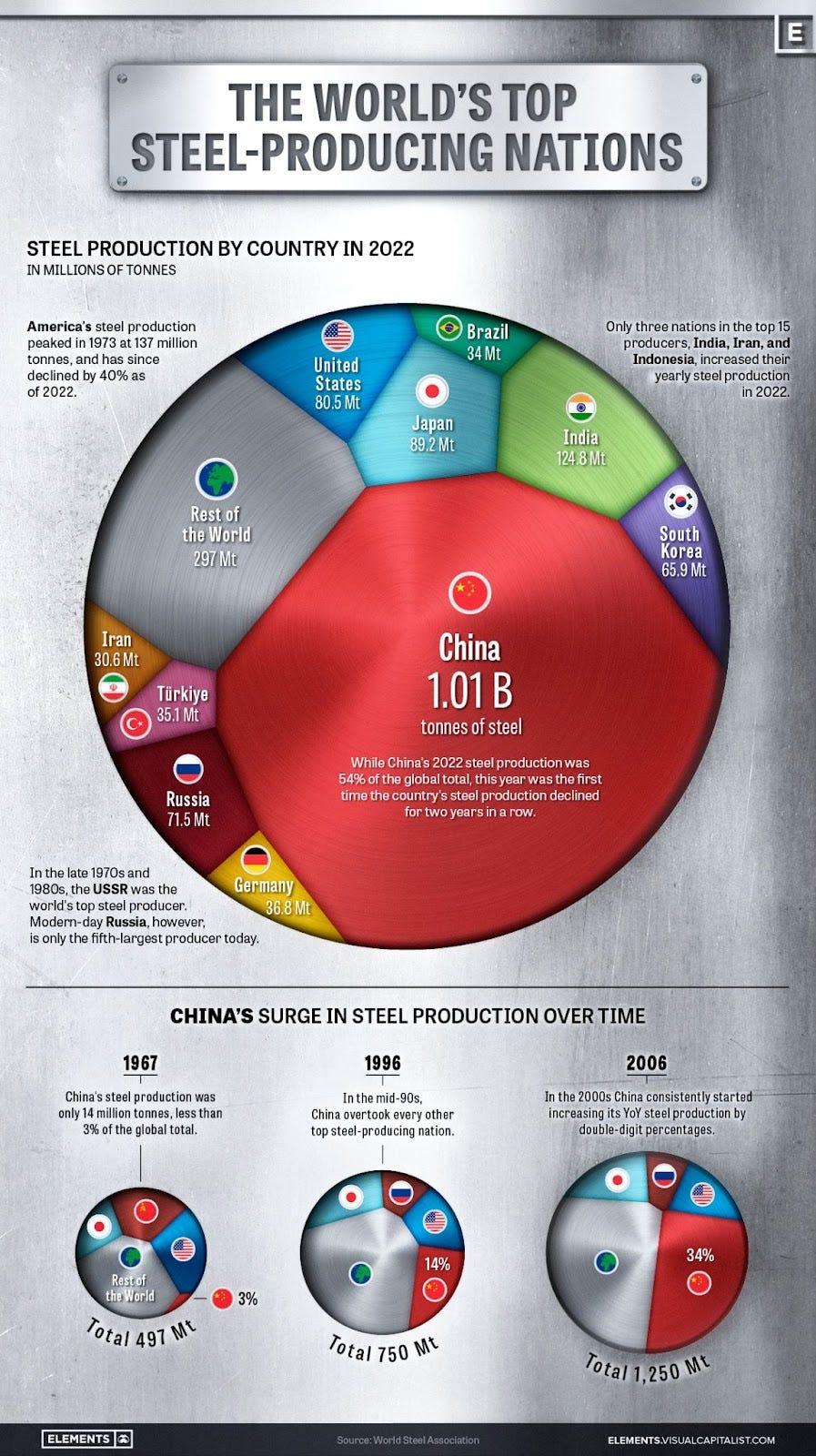

Let’s talk about China for a second. China is the world’s largest producer of steel, it controls around half of the world’s steel production.

But here’s the issue: China doesn’t need as much steel as it used to. Its economy has slowed, and big infrastructure projects—the kind that gobble up steel—aren’t happening at the same pace. So, what does China do with all this extra steel? It exports it. And not just at regular prices—often, it’s sold at rock-bottom rates

To give you an idea, in September 2024, Chinese steel was being sold to India at $462 a tonne, while Indian-made steel cost $574 a tonne. Even after adding import taxes, Chinese steel was still over ₹4,000 cheaper per tonne. It’s no wonder local steelmakers in India are feeling the heat. They can’t compete with prices that low

Dumping—selling products below market value—isn’t just a pricing problem. It can hurt local businesses so badly that they might have to shut down. And once they’re out of the picture, guess who controls the market? The same country doing the dumping. This is why countries like Brazil and the US are already putting up barriers. Brazil, for example, has set strict limits on how much steel can be imported from China. If imports cross that limit, they’re taxed heavily. The US has gone a step further, slapping huge tariffs on Chinese goods like steel and even electric vehicles

Meanwhile, India’s steel story is very different.

Demand here is growing fast, thanks to infrastructure projects, urbanization, and rising consumption. India is now the second-largest steel producer in the world, accounting for around 10% of global production. Companies like Tata Steel are investing heavily to meet this demand. For instance, Tata recently commissioned India’s largest blast furnace at its Kalinganagar plant in Odisha. This is a big deal, but the flood of cheap Chinese imports could threaten such investments.

For years, China’s steel boom was driven by government spending on massive infrastructure projects like highways, skyscrapers, and railways. But now, with fewer of these projects in the pipeline, Chinese steelmakers are stuck with surplus production. And they’re doing everything they can to get rid of it, including shipping it off to countries like India.

Worse still, China is using trade agreements like the ASEAN FTA to reroute its steel through other countries, avoiding higher import duties. For instance, a lot of Chinese steel coming to India now gets routed through Vietnam or South Korea. This clever maneuvering makes it even harder for local producers to compete.

That’s it for this edition, do let us know what you think in the comments and share with your friends to make them smarter as well.