Where is the US-China tech race headed?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

How is the US-China tech race shaping up?

The brave new world of digital finance

How is the US-China tech race shaping up?

The US-China tech race is starting to feel like an arms race.

Washington restricted NVIDIA chips to China, while Beijing retaliated with rare earth export controls. The US poured ~$52 billion into domestic chip manufacturing, while China launched a massive government fund targeting strategic technologies. In an escalating spiral, each move begets a countermove — tariffs, export controls, subsidies, and so on.

This entire race is about who controls the commanding heights of 21st-century innovation: be it AI, clean energy, biotech and so on. And it’s reshaping how the rest of the world behaves, from Europe scrambling for strategic autonomy, to India recalibrating its own industrial policy.

But will this race actually lead anywhere good? Can tariffs really deliver technological superiority to the superpowers using them as policy tools? What are the costs of playing such a game?

At the end of the day, the sense we got is that this is really about zero-sum and non-zero-sum games, and how countries straddle the line between the two. Three recent pieces of research — two academic papers and a Goldman Sachs report — help us think through this chaotic medley of economics and geopolitics.

Let’s dive in.

A new rationale for tariffs

The story starts with a paper by economists Luca Fornaro and Martin Wolf (we’ll call them F&W), titled “Tariffs and Technological Hegemony”.

Traditionally, tariffs have been tools for protecting infant industries from foreign competition until they’re strong enough to compete globally. It’s a playbook China, India, South Korea, and even the US itself followed during their industrialization journey.

But F&W propose something more nuanced in their paper. They argue that tariffs on imported high-tech products (like AI, biotech, semiconductors) aren’t about protecting the weak anymore. After all, the US has an established tech industry. Instead, they’re about deliberately hurting strong foreign players. Additionally, these tariffs are not focused on shielding the present, but rather in securing the future.

Why governments pursue this strategy, F&W argue, is because of the nature of how knowledge is distributed in high-tech industries.

Knowledge spillovers

Have you ever wondered how, at your job, your company stores its knowledge? You indeed have databases and manuals. But for the routine tasks that you do at work, there is probably no set of instructions. In fact, you do them well because of a strong intuition you’ve developed by repeatedly practicing it. Even with a manual, it is hard to teach someone what you know and then expect them to do it well the next day. This is called tacit knowledge, and it’s contained in the employees of a firm.

Now, in comparison to other industries, tacit knowledge dominates in high-tech sectors. That’s because high-tech goods are extremely complex and hard to make. This complexity makes it hard for people to agree upon a singular, certain way of doing things. There is little reason, then, to create a manual, because what seems like the right method today could well be obsolete tomorrow. But, once solved for, tacit knowledge compounds, creating a massive advantage for whoever has it the most.

For these reasons, in the early days of a high-tech industry, there are often divergent approaches between people on how to innovate. As a result, employees often leave and start their own companies, spreading knowledge further. Over time, this process creates high-tech clusters like Silicon Valley — where the return to society from a private firm’s innovation is much greater than their own profit. This dynamic was first documented by economist Steven Klepper.

While F&W don’t use his work as a direct reference, they formalize much of this dynamic mathematically: high-tech clusters generate massive returns because the knowledge spillovers benefit the host country disproportionately.

This creates an incentive for governments. If the profits from innovation mostly stay local, you want innovation happening here — even if you have to make it unprofitable elsewhere. Tariffs on high-tech imports, F&W argue, are intended to do just that: reduce foreign firms’ profits, dampen their R&D investment, and disincentivize talent with lots of tacit knowledge from remaining there. From this point-of-view, tariffs look like a rational strategy, not a mistake.

The cost of hegemony

But, of course, there’s a big catch to this. Tariffs on high-tech goods will reduce the economy’s current GDP. They raise prices for consumers and cut off access to superior foreign technology. However, F&W argue that governments understand this, and are willing to bear short-term pain if that ensures an advantage in technologies of the future.

But here’s where it gets troubling. Tariffs are available as policy tools to all countries. Even in the best case, where tariffs successfully redirect innovation to the host country, the gains come at someone else’s expense. And if the target country retaliates, you get a full-blown tech trade war where both sides lose. On a global scale, F&W say, the welfare of everyone falls in such a trade war. What might be “rational” for one country could hurt everyone else.

There’s another problem too. Tariffs can backfire if they hit inputs essential to your own innovation. The US-China trade war actually exempted certain high-tech components — like specialized computer parts — precisely because American labs needed them.

This becomes more complicated with how globalized innovation has become today. And that is what the next paper covers.

A globalized world

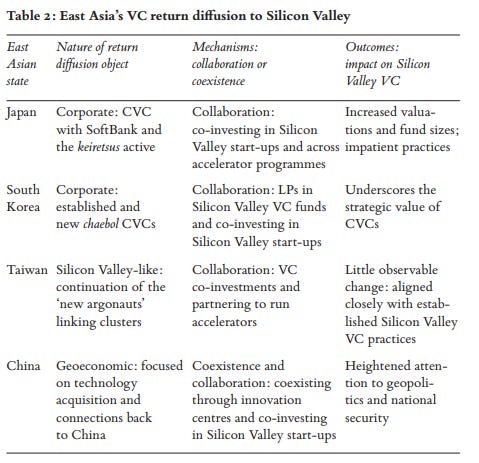

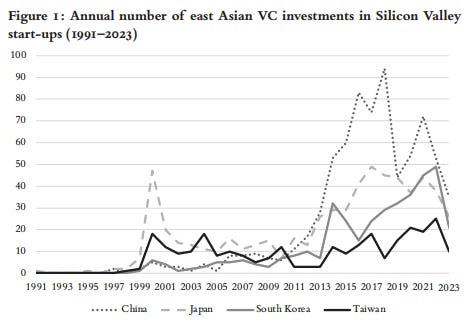

The second paper is written by social scientists Robyn Klingler-Vidra and Ramon Pacheco Pardo (we’ll call them R&R). It tells the story of how a key component of high-tech industry — venture capital (VC) — has truly turned global, instead of being concentrated in one country.

How did this happen? Paradoxically, through a process R&R calls “return diffusion“. The governments of East Asian nations, like Japan, Taiwan, and China, wanted to build their own innovation ecosystems. But recreating something like Silicon Valley at home from scratch was expensive.

Instead, they followed a different strategy — they sent their capital to Silicon Valley first. Many state-backed funds and corporate VC funds from East Asia established offices in the Valley. They learned the rules of the game, like deal structures, due diligence, and so on. The funds of Samsung and Tencent have become major investors in American startups.

These same funds got good at VC and began installing Silicon Valley practices back home. This helped contribute to a new wave of entrepreneurship in their countries. But they didn’t just absorb Silicon Valley’s practices — they began changing them permanently, too.

For one, since their entry, the cheque sizes became much bigger — SoftBank’s $100 billion Vision Fund, for instance, reshaped startup valuations and funding dynamics. Secondly, they popularized the concept of corporate VC, where an existing big company (like Google) did its own startup investments.

They became a part of the global innovation ecosystem that no one could do away with. Because of this, the US’ share of global venture capital went down from 90% twenty years ago, to barely above 50% today.

More importantly, as a result of these changes, the tech hubs of various countries are now deeply entangled. Silicon Valley and Shenzhen aren’t isolated, but rather are part of a transnational system where capital, talent, and ideas circulate despite geopolitical tensions. American venture firms have branches in China; Chinese tech giants invest in US startups, and VC funds of both countries often co-invest in the same startups. This, of course, is a more positive-sum game than tariffs.

This creates a fundamental tension with policies that prioritize self-sufficiency. By its nature, VC routes around barriers, seeking the best opportunities wherever they are. A pure import tariff strategy runs against the grain of how these networks have evolved. And disentangling this whole edifice will be costly.

Mutually-assured pain

The real world, it seems, lies in a messy space between what both papers describe, as per a recent Goldman Sachs report. It shows the difficulty of governments trying to re-nationalize innovation in a world where supply chains and capital are globally networked.

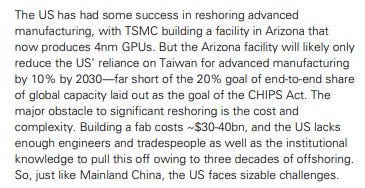

Let’s start with the semiconductor industry, which has a huge global supply chain. The US has been attempting to get back a lot of semiconductor manufacturing to its base, primarily to reduce reliance on Taiwan. To that end, it invited TSMC to build a massive plant in Arizona. However, the plant has struggled with delays, cost overruns, and shortages of specialized workers that Taiwan doesn’t really lack.

China, on the other hand, has been driven by necessity. As investor Paul Triolo says in the report, China had little incentive to make its own chips until US tariffs came along. Now, China is trying to build the entire semiconductor supply chain within their borders. However, such a goal is far too ambitious, even for a large country like China.

The power of tacit knowledge is most visible here. Despite being a global leader in the semiconductor market, the US is finding it difficult to replicate the success of TSMC. China is also fighting an uphill battle when it comes to building its own lithography machine, while a firm like ASML continues to advance at the frontier, benefiting from decades of accumulated tacit knowledge. Despite their efforts at self-sufficiency, the US and China have both failed at localizing the most advanced parts of chips.

In critical minerals, the situation looks far more one-sided. China controls ~70% of global rare earth mining. Its tightening of export controls has proven to be a powerful retaliatory tool. In response, the US has eased some semiconductor restrictions — a tacit acknowledgment of mutual dependence. Meanwhile, they’re also trying to develop alternatives to rare-earths. However, Jack Lifton, the co-chair of the Critical Minerals Institute, thinks that for the US, self-sufficiency in critical minerals may just be a mirage.

Lastly, talent, which has been a powerful edge in American innovation. But now, that edge is eroding — tougher visa rules and security restrictions have pushed some researchers toward other destinations, like Canada, Europe, or even back to China.

Neither here, nor there?

To a large degree, the US and China are playing remarkably similar games.

Both are pouring massive subsidies into strategic industries. Both are using export controls and investment screening to limit the other’s access. Both are trying to attract (or retain) talent while restricting flows to rivals. Both talk about self-sufficiency while remaining deeply dependent on global networks.

And both face the same contradiction. The very policies meant to secure technological leadership create inefficiencies that could undermine it. The pursuit of monopoly, it seems, could slow the pace of innovation it aims to secure.

This is not to say that economic interdependence is a cure to everything. As we’ve covered before, it can be weaponized by countries. Having one’s own industry is also important. But it’s worth evaluating the lengths to which one is willing to go in the service of self-sufficiency. Moreover, the rise of high-tech is deeply intertwined by networks that span across borders.

And that’s the uneasy world we live in today: between self-sufficiency and interdependence. We seem to be heading toward competing ecosystems — more self-sufficient than before, but still interconnected at critical points. The US may lead in frontier innovation, while China may lead in deployment and scale.

But both of them, it seems, are locked in a competition where a win might not feel like one.

The brave new world of digital finance

The digital and financial worlds have a fraught relationship.

Digitisation can fundamentally transform how money works — opening up new possibilities for how value is created, stored, transferred and accounted for. We, in India, have seen just how remarkable that change can be. In just the last decade, technologies like UPI have completely changed how we carry out commerce.

At the same time, though, money is a social interface. It connects people, businesses, and the state — each of whom come with their own peculiarities. Try to change how money works, and each of them can create friction. Digital finance, it turns out, isn’t just a matter of technological innovation, but of solving a series of people-centric challenges.

This is why it is so hard to bring these two worlds together, and why experiments with digital finance have been so uneven.

A new report from the Centre for Economic Policy Research offers a panoramic view of how these experiments are going. Here are five themes from the report that stood out to us the most.

Theme 1: A clash of architectures: public utility vs. private stacks

What makes the UPI so good? To the CEPR report, it’s the architecture.

Any good payment system tries to solve three big problems: how do you accurately exchange information on the transaction, how do you ensure that the payer actually authorised the payment, and how do you actually move the money. Getting this right, especially between banks, requires remarkable coordination.

UPI’s genius came from building neutral, public rails that different banks could plug into, and instantly connect to everyone else on the network. This ensured that everyone across our economy could use the system, without a single entity trying to monopolise it all. The breakthrough, here, wasn’t in developing a single application, but in architecting a backbone that many apps could sit on.

Once you think of digital finance systems as architectures, you’re no longer limited to settling payments. You can do more.

Take Brazil. Like us, they created public rails for payment — with Pix. But then, they started adding more building blocks on top, which let their financial system do more. For instance, they set up “Open Finance”, a system that makes financial data portable between different institutions. This allowed all sorts of new use cases — from entities looking at your payments history to give loans, to permitting clean payment flows within apps. By late 2024, 62 million accounts in Brazil had consented to share data.

The country’s next frontier, it appears, is to do away with the current API-based systems, where any financial institution can become a “gatekeeper” to your money and data. Instead, Brazil’s trying to set up a tokenised platform called “Drex”. Among other things, Drex allows you to program your money, which lets you build in all sorts of interesting structures — like complex transactions that get settled instantly, without you having to trust that the other party comes through.

The crucial point is this: all these new features and capabilities come out of the rails that a country has set up.

Like India, Brazil sees these rails as public utilities — while the private sector competes to create the best interface on top. But there’s another, clashing approach. A country like the United States, for instance, has leaned toward a model where private companies create the payment infrastructure as well. It recently passed the GENIUS Act, which created a framework under which private companies could create stablecoins.

Which is the superior approach? We aren’t sure. Private companies can innovate faster. But they can also set up walled gardens that don’t work well with each other. Without a clearing system at their core, they may not work as currencies at all.

Theme 2: The death of cash-like anonymity

How do you think about privacy in an era of online payments?

Back when people used cash for most transactions, privacy was the default. There was simply no way of collecting and processing data on how payments flowed. Every digital payment, in contrast, generates a record. This, the report argues, creates a structural “privacy gap”.

In general debates, privacy is usually treated as an issue of civil liberties. This makes privacy concerns easy to brush away — if they’re your right, specifically, you’re allowed to surrender it. And so, if people give up their data for convenience, that’s a voluntary choice, not a systemic failure.

CEPR’s report tries to reframe the debate.

Now, there are some places where your data should legitimately be processed. So much of digital finance relies on things like credit scoring, compliance, and fraud detection. They’re only possible if transactions are traceable. More often, however, your data is analysed for insights that are used against you — for instance, you might be charged more for things you habitually buy online.

The report argues that when you surrender your privacy, you don’t just harm yourself — you harm others too. Protecting your own data, alone, is pointless, because someone can use other people’s data to predict your behaviour. If you frame privacy as an individual right, you miss this altogether.

A better way of seeing it, perhaps, is what economists call a “public good” — somewhat like clean air. Society benefits from clean air as a whole, but individual people have to sacrifice something to ensure it. Left to their own devices, people repeatedly choose to pollute instead of doing good by society. The report argues that there’s something similar at play here — the incentives of the system are such that privacy will always be ignored.

The answer, the report argues, is to design our financial system in a way that protects people’s privacy by default. For this, specific designs like offline balances or cryptographic zero-knowledge proofs will have to be hard-coded into the architecture itself. That can only happen at a time like this, when these systems are being set up. If not, digital money inevitably becomes a surveillance tool.

Theme 3: An illusion of stability

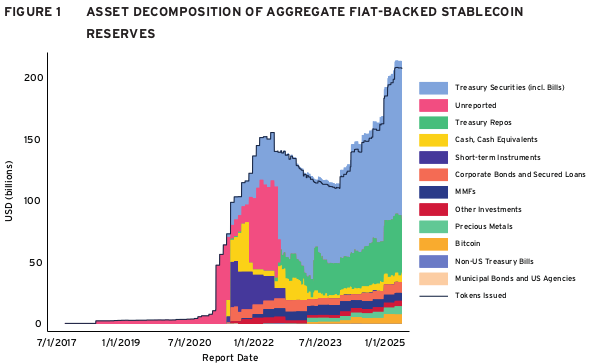

Stablecoins are marketed on a simple promise: one token equals one dollar. But how well does that promise actually work? The report dives into the plumbing behind this promise. It finds that this promise isn’t automatically ensured by software, but is put together by the institutions sitting in the background.

The key idea is this: stablecoins are, indeed, “backed 1:1”. On paper, every stablecoin has a corresponding dollar sitting somewhere in the issuer’s bank account, or in some other dollar-denominated asset. But that’s different from you being able to exchange a stablecoin for a dollar whenever you want.

We got an ugly reminder of that in 2023. Circle, which issues the stablecoin USDC, had backed every coin on its chain by depositing the same amount of money in its bank. That bank, unfortunately, was Silicon Valley Bank. When the bank collapsed, back in 2023, Circle suddenly realised that it had $3.3 billion trapped inside. There was a sudden panic, and holders of the coin rushed to sell. The token’s price crashed to $0.87. It only recovered after emergency government intervention guaranteed those deposits. In the interim, Circle was forced to sell billions in assets to meet redemption requests.

To CEPR, stablecoins aren’t really like digital cash. They’re more like money market funds. In normal times, they are excellent at connecting banks with blockchain-based systems. But in times of stress, frictions can suddenly appear. There are no institutions that will guarantee final settlement. There’s no easy way of redeeming your money. If things start going wrong, you’ll have to stomach a massive discount, along with all sort of other charges, to get your money out.

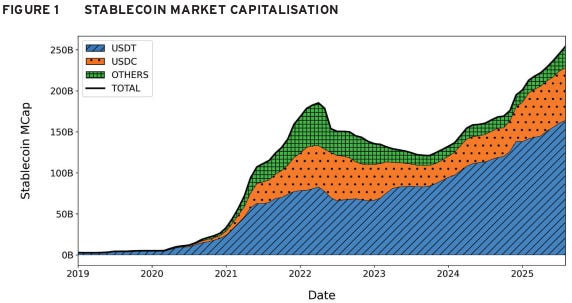

The consequences of a failure are enormous. The market for stablecoins is now worth over $270 billion. It is also concentrated in just two entities — Tether and Circle — who control 85% of the volume. If either of them fail, it could spark a crisis of global relevance.

This doesn’t mean stablecoins are bad — just that they’re primitive. The value of money comes, in part, from how it behaves in a time of stress. Stablecoins, on the other hand, only have value if the markets are confident. Without institutional safeguards, like lender-of-last-resort backstops or strict capital requirements, they won’t really become “digital dollars” in a true sense.

Theme 4: Smart money and “singleness”

Central bankers obsess over the idea of “singleness” — the principle that a Rupee, in all its forms, must always be worth a Rupee.

But we’re slowly entering an era of programmable money, with rules of what it can buy, when it can move, and more. For instance, a government can give people money that is coded only to work if you’re buying food. Or it could make welfare payments that don’t work for liquor purchases. Similarly, if it’s trying to drum up economic activity, it could send people money that expires, say, in three months.

If different Rupees behave differently, it challenges the idea of “singleness”. In a way, it creates many types of money, instead of a single currency. That sort of fragmentation makes it far harder to run a monetary system, and can create a variety of unexpected crises.

But given that this is now a distinct possibility, it’s worth asking: are the trade-offs worth it?

The report, at least, argues that they are. If you can shape better behaviour through the very rules of how money works — for instance, by preventing its use in gambling — the gains could outweigh the risk of a fractured currency.

Taken to its logical conclusion, though, the world of programmable money could be very different from ours. Instead of having perfectly fungible Rupees, in the not-so-distant future, we might all have a spectrum of assets, with carries different values, and different degrees of freedom.

Theme 5: Algorithmic credit

Loans, arguably, are one dimension where digitisation could completely change how money behaves. So far, the story of digital lending has been one where transaction costs are lower, and money can be disbursed easily. This is, however, just a start. Through ledgers, data and programmable money, borrowing can become an entirely different experience.

We’re already seeing some of this in practice. Companies are using alternative data and machine learning to predict your ability to repay loans better than your credit score.

But it can go much further. One of the oldest problems with lending money, for instance, is enforcement — or the challenge of ensuring that someone actually pays back a loan. This is a problem that technology can now solve, through what the report calls “digital collateral”. Here’s one example: consider a large e-commerce platform, for instance, that a merchant relies on for their revenue. Their future revenues could become the collateral for a loan. The platform could offer them loans, and automatically deduct loan payments before the merchant touches any money.

Is this a good thing to have? Is it a dystopia? It’s perhaps a little bit of both: it can massively expand people’s access to credit, but it can also tie them to data monopolies from whom they have no privacy.

New design choices

If there’s one big takeaway from these disparate themes, it is this: the world of digital finance isn’t merely one with online payments. That notion is already outdated. We’re entering a world with fundamentally new design choices. These choices will determine what people can do with their money, what happens when things go wrong, how we should protect people from those that can see the entirety of their digital footprint, and more.

What choices do we make? That isn’t a question of money or technology. It is a political question. We’re in a world where we can engineer any structure we can imagine. The hard part is knowing what structures we want to live with.

Tidbits

Credit Cards: A Tale of Two Strategies

Mid-sized lenders like Kotak, RBL, and IndusInd are slowing credit card issuances amid rising defaults, while HDFC Bank, SBI Card, and ICICI added over 3.7 lakh cards in October alone.

Source: ETChina Turns Down Nvidia’s H200

White House AI czar David Sacks says China is rejecting Nvidia’s H200 chips to pursue semiconductor self-reliance, putting at risk a potential $10 billion annual revenue opportunity for the chipmaker.

Source: BloombergUnemployment Falls to 7-Month Low

India’s unemployment rate dropped to 4.7% in November from 5.2% in October—the lowest since April—with rural joblessness at a record 3.9% and female workforce participation climbing to 35.1%.

Source: BS

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Pranav.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Interesting topics. Thanks team!!!

Hey! It was a great read thanks. But something came to my mind, the thing you guys mentioned about the singleness isn't an almost similar idea used for Loans? Take the example of education loan I cannot use my loan education loan amount on anything but the college, I don't even get the money in hand, it goes directly to the college. So, it's like that the amount has only single use. Also, it seems that they might become a great tool to curb the corruption. Would love to read more about them if you guys are planning to write more on that.