When Cloudflare sneezes, the internet catches a cold

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

Just a quick heads-up before we dive in. The Wakefit IPO is open now. We wrote about them earlier — you can read the full story on Wakefit here.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

How to break the entire internet, twice

Growth without pollution

How to break the entire internet, twice

Twice, over the last three weeks, large parts of the internet suddenly came undone. Websites that regularly draw millions of visitors — ChatGPT, LinkedIn, Spotify, and more — became impossible to reach. We weren’t immune either.

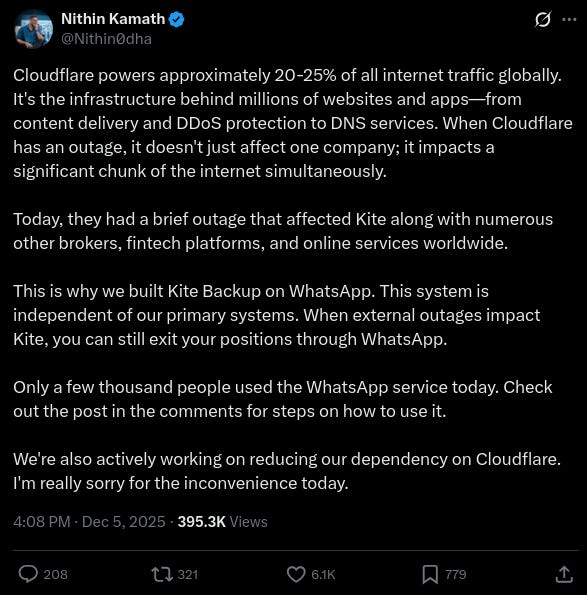

These were “world scale” incidents, but they were borne out of something painfully ordinary. In both cases, a single, little-known company called Cloudflare made a minor update — the first time, because it was modifying some permissions for its database systems, and the second, because of a tiny bug that had been around for years, but had never acted up before. Both were enough to strangle much of the internet.

How did tiny failures inside one company infect so much of the world? To understand that, you need to understand why the internet, today, is fundamentally different from the “web” it began as — and how this is creating single points of failure.

Cloudflare and a centralising internet

Most people — at least most non-engineers — who think they understand the internet are working off an outdated idea. They see the internet as a decentralised, formless cloud — a web — with innumerable computers, including your own, that talk to each other through infinite pathways.

That may be true of the core technology beneath the internet. But as it has grown, layers have been built on top of it all, which behave very differently. The internet is no longer a flat mesh that directly connects the world’s computers together. Instead, it is slowly centralising. A new hierarchy is coming into being. At the heart of the internet, there is, now, a small cadre of infrastructure providers who manage, route, and secure most of its traffic. These now make up a meta-layer that most of the internet is wrapped within.

One of the most critical of these is Cloudflare. While Cloudflare is a private company, it is best understood as a global utility — it is to the internet what a grid operator is to our electrical systems.

The pre-Cloudflare internet

In the early days of the web, websites faced two big challenges: speed and security.

You ran websites out of a server sitting in one location — say, in Bengaluru. If one accessed that website from Bengaluru itself, it would load relatively fast. If one was all the way in America or Europe, for instance, that data would have to travel across the world to get to them. Naturally, it would be horribly slow.

Securing that server was a headache as well. Hackers and other bad actors could clearly see your specific IP address — which told them exactly where to direct their attacks. The only means of handling this was physical. People would connect their server to a separate, physical computer that all traffic was routed through — called a “firewall”. This would study all traffic coming in, and if a request seemed unusual, would block it.

Firewalls couldn’t protect you from everything, though.

For instance, there was only so much traffic a server was built to handle. If you got more requests than that, they would get overwhelmed. This used to be a regular feature of the internet — a niche website would feature on a popular platform like Reddit, drown in a flood of traffic, and collapse.

Eventually, bad actors learnt to weaponise this. If someone wanted to take your website down, they didn’t have to break into your system. They could simply overwhelm its connections with noise. In what were called distributed denial-of-service attacks or “DDOS”, they would flood your server with fake traffic, choking its bandwidth and forcing it to crash. By the mid 2000s, this was a common nuisance on the internet.

The rise of content delivery networks

Large internet companies had solved some of these problems by the late 1990s itself, by bringing their content closer to users.

That was when the company Akamai pioneered “content delivery networks” or “CDNs”. It set up a network of servers across the world, and pre-loaded “cached” copies of large parts of its clients’ websites on all of them. You wouldn’t have to connect to the original server to visit a website. Most of it would simply be delivered from the server nearest to you.

This was a huge performance boost. Loading a website became much faster, while original servers were relieved from a lot of traffic. Doing this was horribly complex, however. Akamai only marketed the service to large companies, like Yahoo! or Disney. If you ran a small, boutique website, it was out of your budget.

In the mid-2000s, though, Cloudflare’s founders realised that those same CDNs could be used to set up an internet security service. They could do whatever physical firewalls did right out of the cloud. At the same time, CDNs could beat away DDOS attacks as well. Overwhelming a single server was easy; overwhelming a large network that fed thousands of websites was not.

Meanwhile, their cleverly engineered network also made websites faster.

More impressively, Cloudflare wasn’t thinking of this like a traditional enterprise service provider. Instead, it threw the service open to the public. Unlike Akamai’s long sales and onboarding process, Cloudflare let you get on-board in five minutes, by simply changing some settings. It even offered a free tier. Suddenly, small websites could afford premium security protections and speed boosts. It would soon take the world by storm.

What Cloudflare does

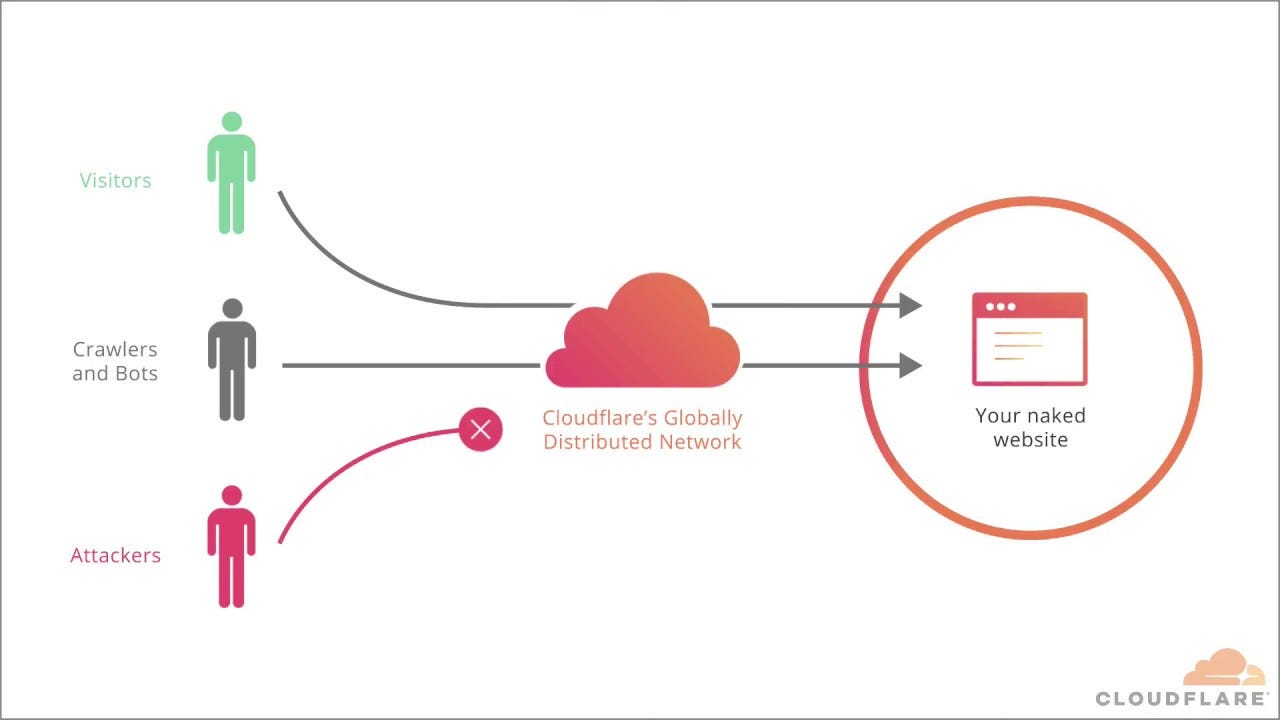

Cloudflare acts as a “middle layer” between you and a website.

When you request a website linked to Cloudflare, it doesn’t blindly travel across the world. Instead, Cloudflare quickly pushes it to a nearby hub and checks “Is everything okay with this request?” If it’s safe, Cloudflare serves the content cached in that server itself. If the request looks suspicious, Cloudflare stops it right there. All of this is invisible to you, but it makes the connection both faster and more secure.

Protecting IPs

Traditionally, any website’s IP was exposed to the world — attackers included. A malicious actor would know exactly where to look for vulnerabilities.

Cloudflare, however, masks one’s original IP address from the world, acting as a “Reverse Proxy”. If you use their service, whenever someone looks up your website, your domain doesn’t point to your actual server, but that of Cloudflare. Cloudflare then connects to your server at the back-end. Your server is invisible to the public internet; it exists only for Cloudflare.

The firewall

Once Cloudflare takes requests on its own servers, it can do many things to protect your website. For one, it just absorbs many more requests than any single server can. This makes sure your servers don’t drown in traffic — whether from attackers or otherwise. If it needs to fetch anything from your original server, it can control how much traffic gets there, rate-limiting it when necessary.

It can also run all sorts of checks on any incoming request. If it thinks something harmful is coming in — like a bot, or traffic from a malicious source — it can throw up challenges to verify that it’s legitimate. If you’ve ever seen something like this, for instance, you’ve seen Cloudflare in action.

Efficiency

Cloudflare uses something called “anycast routing”. Its grid of servers store cached copies of a website’s content at different locations in the world. Those servers all have the same IP address. When users seek that IP address, their request doesn’t go to a specific location — they’re simply routed to whatever’s closest to them. Once a request passes Cloudflare’s checks, that close-by server starts loading the website up for you — and so, data travels the shortest possible distance.

If you look for a website from Mumbai, for instance, you connect to a Mumbai server. Someone else that searches for the same website in London reaches the London server. Pages, as a result, load much faster for users everywhere.

Centralisation and tail risks

Cloudflare gives websites speed and resilience for cheap. That has made it central to the entire internet.

Every single second, on average, Cloudflare’s network gets over 80 million requests — or one-fifth of the entire traffic of the internet. According to one survey, four out of every five websites that use a reverse proxy service go through Cloudflare. This includes some of the most critical parts of the internet — like major banks, or governments. By one estimate, nearly half of the world’s 10,000 most popular websites use the service.

The economic push for centralisation

This importance comes, in part, from the fact that this industry rewards centralisation.

To do what it does world-wide, Cloudflare runs massive servers in over 125 countries. It’s impossible to fund this sort of infrastructure without scale — you need millions of paying customers to all plug into the same infrastructure.

This becomes all the more important when it deals with massive DDOS attacks — where millions of hacked devices bombard a website simultaneously. There are only a handful of companies in the world that can absorb such volumes of traffic. The larger a company’s customer base, the more likely they are to do so.

Scale also brings intelligence. Because Cloudflare sees one-fifth of the web’s traffic, they also see roughly one-fifth of the malicious activity on the internet. This gives them a large base of knowledge to rely on. If a bank in New York faces a new type of attack, for instance, Cloudflare can instantly update its rules across the world — and a small e-commerce store in Delhi can benefit from that update milliseconds later. The largest provider, in a sense, becomes the safest provider.

The failure case

There is a paradox at the heart of the service, however. While Cloudflare creates micro-resilience, bringing exceptional security to individual websites, it creates a massive systemic risk. If Cloudflare goes down, large parts of the internet go with it.

Websites that connect to Cloudflare have absolute dependency on it. You can’t just turn it off. If Cloudflare fails, there’s no other path for the public to reach your server — at least not soon. Your servers could be up and running, but they’re effectively “air-gapped” from the internet.

Now, failures are rare. But if they happen, they can be instant. Cloudflare uses something called ‘Quicksilver’ — which replicates information across its servers everywhere. Usually, this means everything from domain records to security features get replicated everywhere instantly. But if something problematic goes in, there’s no “safe” location in the world. A faulty update doesn’t travel through the system slowly; it rips across the entire internet.

This is what we saw recently.

Take the first of the two outages. Somewhere, a tiny file that tells Cloudflare’s systems how to stop bots bloated to twice its size, after some lines in its code got duplicated. That made it bigger than the memory budgeted for it. Its servers started throwing up error messages in response to most requests

For over three hours, large parts of the internet became unresponsive. Some of the most important services in the world — AI services like ChatGPT, social media platforms like X, streaming websites like Spotify, communication platforms like Zoom — some of the most critical parts of the digital economy were all shuttered.

All it took was a single malfunctioning file.

Black swans on the internet

When Cloudflare does its job well, you don’t even see it.

It regularly fights off massive, coordinated attacks, from thousands of virus-laden devices firing together. That isn’t what brought it down. What brought it down was a silly mistake in a file update. It seems almost laughable, but this is a curious picture of what the internet looks like in 2025.

We’re drifting, slowly, to an internet with central hubs and single chokepoints. This is, indeed, necessary — the free-floating structure of yesteryears is simply inadequate for the sheer weight that it now supports. But it adds weird new fragilities that we have to learn to either live with, or design around. This is a world of tail risks and butterfly effects, where tiny missteps can avalanche into world-wide catastrophes.

Maybe the cost of efficiency is that we lose our margin for error.

Growth without pollution

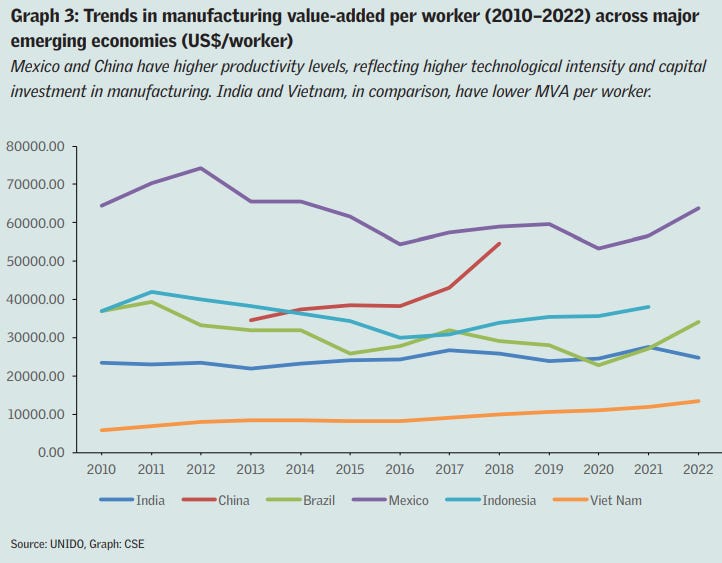

The Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) put out a long paper on a basic but difficult question: how can countries like India still build factories and jobs while reducing emissions? In the past, countries became rich by growing first and worrying about pollution later. That option is now closed. The climate is changing too fast.

So, the report asks: what does development look like in an era where emissions are no longer an option?

CSE takes a clear lens to the problem: clean-technology manufacturing. A low-carbon world still needs hardware — solar panels, batteries, electric vehicles, and more. Someone has to make all this. Today, a small group of countries, especially China, controls most of that manufacturing.

Can poor countries step in, take the baton, and find new ways to industrialise?

The dilemma of industrialization

In theory, we already know the path to development. Large numbers of people in developing countries still work in low-productivity agriculture and informal services. To raise their incomes, you need to shift them to higher-productivity work: like factories, or organised services.

But there’s a problem: historically, this shift has always come with a big surge in energy use. Only, our most common sources of energy — coal, oil and gas — cause emissions. And that is a luxury we can no longer afford.

So, countries like India are pulled in two directions. On one side, you can’t tell people to stop wanting a good life — which creates tremendous pressure to keep adding power plants, roads, factories and housing. On the other, this path comes with heatwaves, floods and crop losses.

How do you get around this dilemma?

To CSE, the answer is “green industrialisation“. This lets us tick both boxes at once: build an industrial base and jobs, but around low-carbon technologies. If clean tech is a major growth area, globally, to be stuck as a buyer is to miss a development opportunity. On the flip side, if we can make more of that hardware at home, we can control our own energy transition.

Bringing in these opportunities also eases the transition itself. There are entire regions, today, that are built around a single coal mine or refinery. They’re likely to fight a transition tooth-and-nail, not because they want emissions, but because they need a means of livelihood. The route to easing the politics of the transition is to introduce replacement jobs.

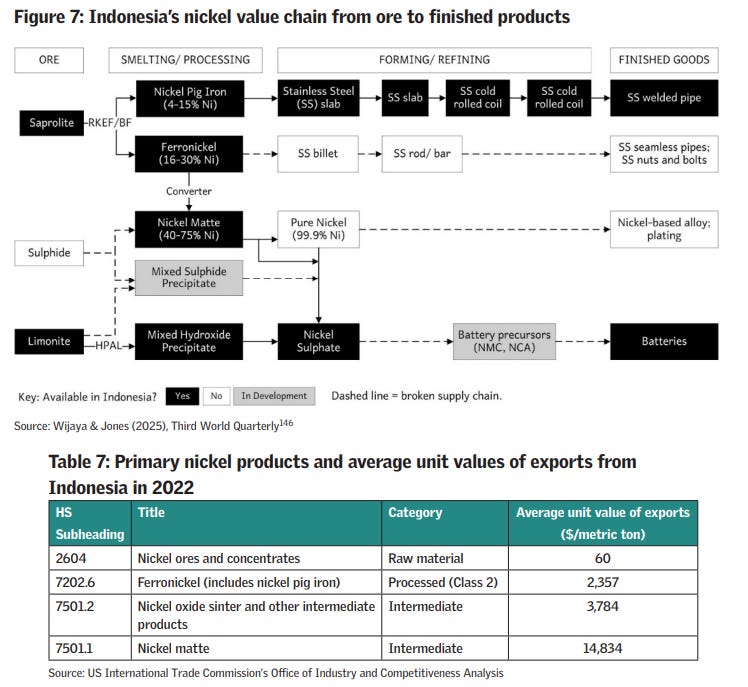

There’s one complication, though: at least in the short term, “green industrialisation” does not always mean lower emissions. Nickel, for instance, is critical for the green transition. Yet Indonesia’s nickel smelters are powered by captive coal plants.

Similarly, as countries move up the value chain for battery materials, their emissions go up.

A big market dominated by a few

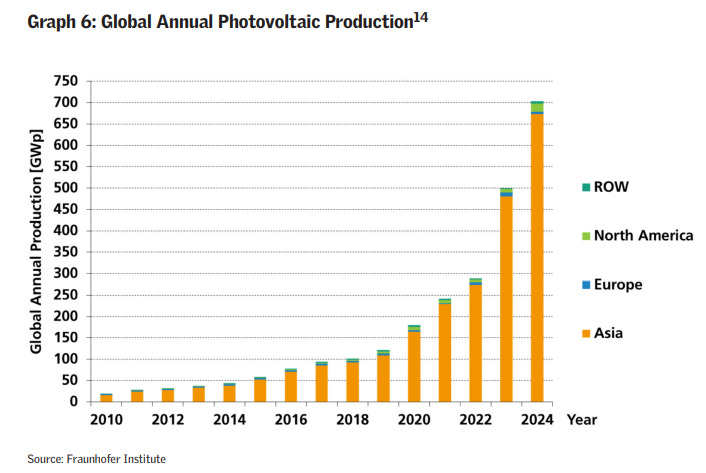

In 2023, the global market for clean technology was about $700 billion. The International Energy Agency expects it to grow to more than $2 trillion by 2035. This is, in short, a massive opportunity.

The dragon in the room

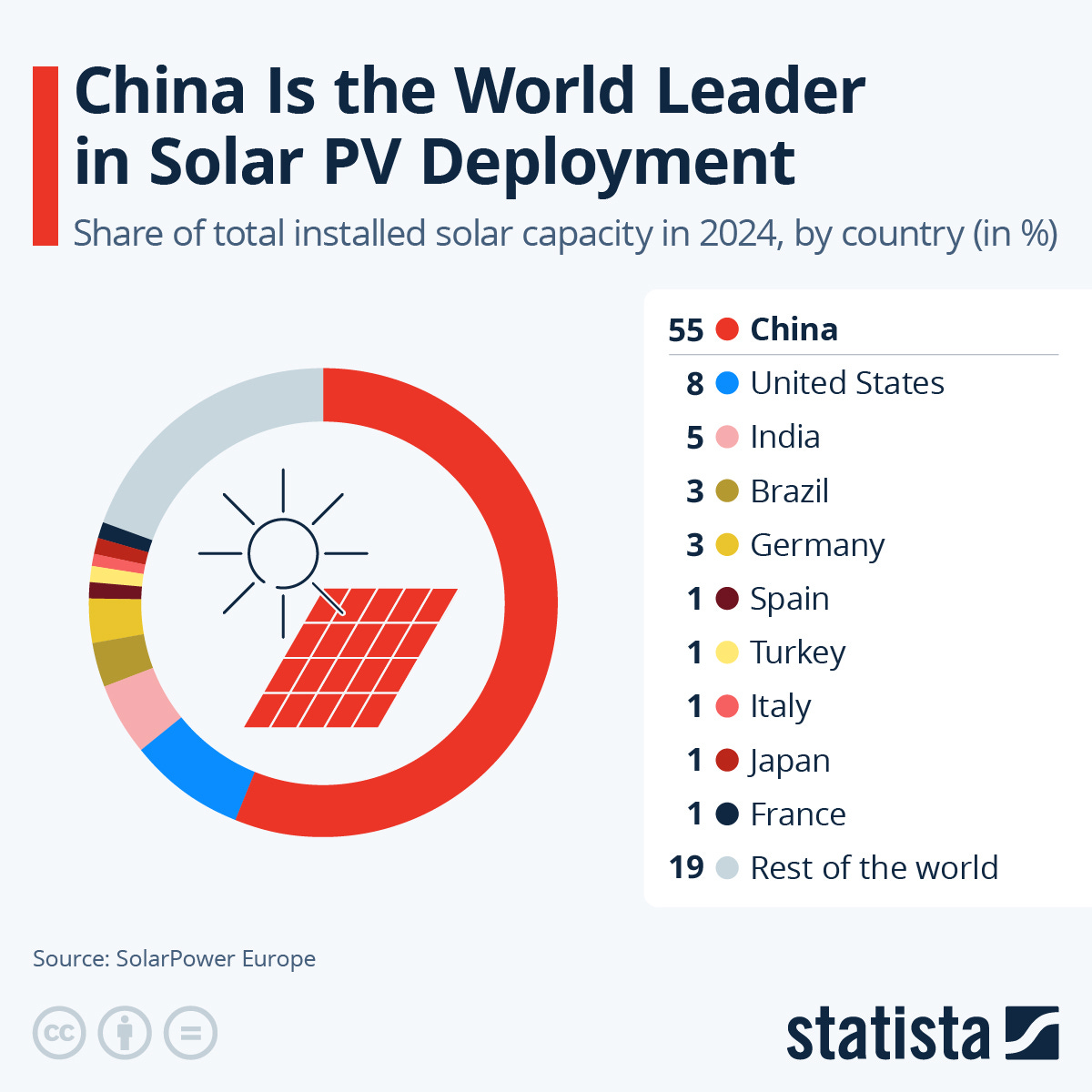

But who actually makes all this? At least in 2023, around 75% of all new clean-tech manufacturing investment happened in China. The rest of the emerging and developing world — countries in Latin America, Africa and much of Asia — together accounted for less than 5% of global production.

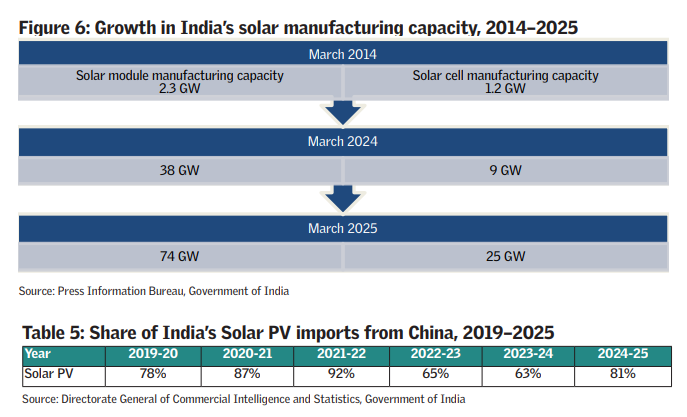

Take solar energy: roughly 85% of the world’s solar PV output comes from China.

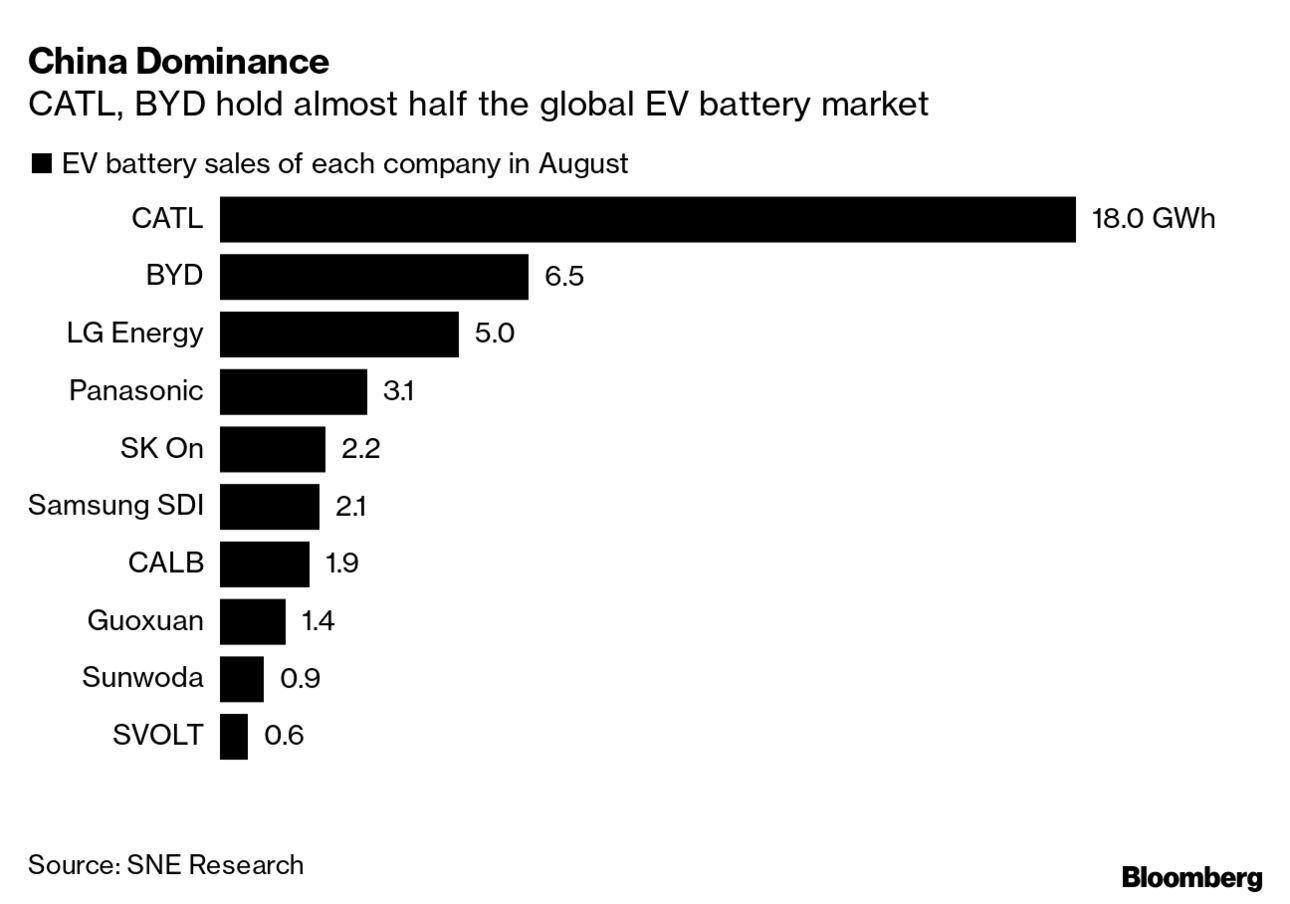

Or consider batteries: in the first half of 2025, just two Chinese companies — CATL and BYD — made more than half of the world’s EV batteries.

This is a double-edged sword.

China’s scale effectively subsidises the world’s energy transition — they’re why solar and batteries are now cheap enough for many countries to install. The cost, though, is that it runs firms in other countries out of business. To large parts of the world that need that employment, those low prices are cold comfort.

It also pushes countries into import dependency — making them buyers, rather than makers, of the technology. China has shown it is willing to use its weight in supply chains for strategic ends, by placing export controls on key materials, and entering into trade disputes over industrial policy.

That doesn’t mean China doesn’t bring jobs abroad. Chinese firms have committed over US$227 billion across 461 green manufacturing projects in 54 countries since 2011 — giving them access to much needed technology and capital.

In essence, for developing countries trying to build their own industries, China is both a potential partner and a potential chokepoint. So the question, as CSE frames it, is not how to slow China down, but how to engage strategically, without becoming dependent.

How China built this lead

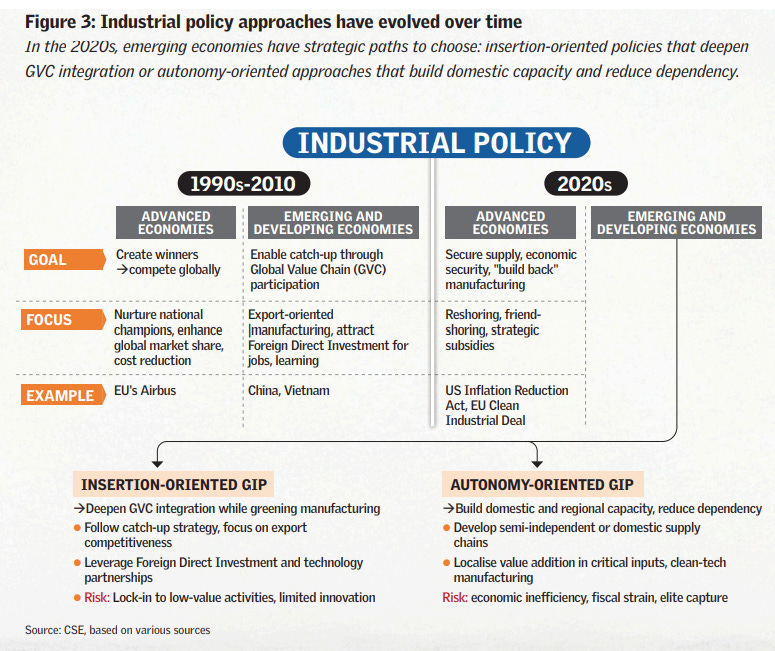

This sheer dominance is, at least to some extent, a product of deliberate state support, continued over many years.

Since the 2000s, China has offered a package of sops to its solar, wind and EV manufacturers — cheap land, concessional loans from state banks, tax holidays, direct grants, and more. It also directed large amounts of cheap financing to these sectors, through its state-owned banks.

Take EVs. For a long time, the Chinese state has set production targets for electric vehicles, subsidised purchases by consumers, and invested in domestic battery firms. By one estimate, from 2009 to 2023, the Chinese state spent around $230 billion on building its EV sector. The results show. By the early 2020s, EVs made for roughly half of new car sales in China, while the country also became the world’s largest car exporter.

China’s success has pushed other rich countries into industrial policy. For instance, at least for now, the US Inflation Reduction Act offers generous tax credits for clean technologies. The EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan allows more subsidies for local firms.

Curiously, the same countries are blocking others from using such policy tools. China, for instance, recently hauled India to the WTO for its battery and EV subsidies.

A sea of trade-offs

So what can developing countries do to recreate this success? Turns out, that’s easier said than done. China, of course, managed to. But others have struggled to replicate that success.

Industrial policy is hard

Indonesia, for instance, tried resource nationalism. It had large reserves of nickel, and instead of exporting the metal, they banned exports and forced domestic processing. As a result, nickel-related exports grew from $6 billion in 2013 to $30 billion in 2022.

But was it worth it? Indonesia moved up the value chain. But it hasn’t held on to a lot of value. About three-quarters of that refining capacity is controlled by Chinese firms, and soak most direct profits. The country has also seen severe environmental damage — especially the smelters themselves run on coal.

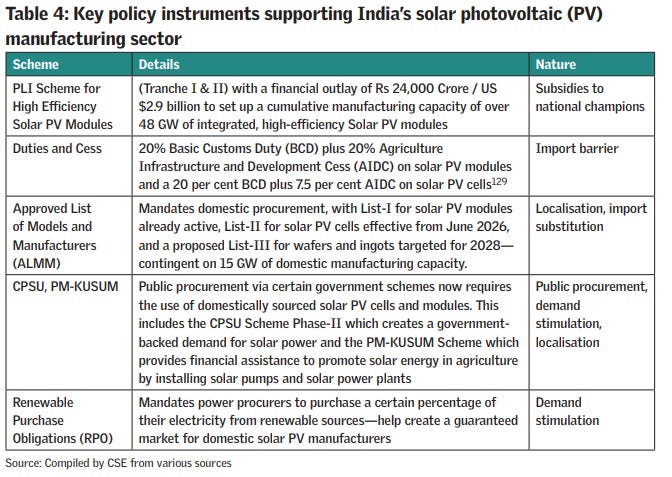

Or take our own experience. Our solar manufacturing expanded on the back of schemes like PLI or ALMM. And yet, about four-fifths of solar PV imports still come from China. Our own industry is already facing a supply glut. Nearly all of our panel exports go to a single market — the United States — and they’re hardly a trading partner one can trust.

Industrial policy is hard. Capturing real value through it is even harder.

Structural barriers for latecomers

What makes it so hard to be the next China?

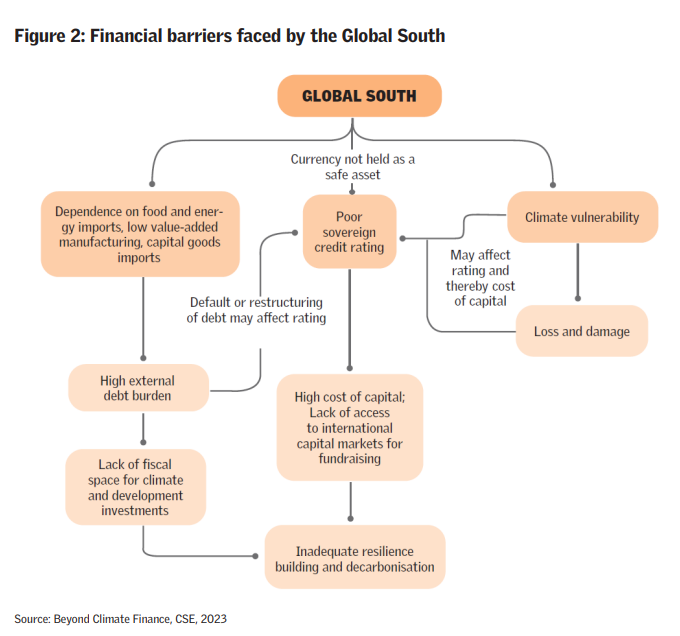

First, the cost and flow of money. Out of $1.3 trillion in annual global climate finance, only about 19% goes to developing countries. When these countries invest in clean energy, they typically pay commercial rates – at nearly double the financing costs of rich countries.

Second, many emerging economies get trapped at the low-value of global value chains. Take our solar capacity: we largely import wafers and cells, and simply bunch them together into modules. This can create “low-end lock-in“: you end up becoming a permanent assembler, with little technological learning and thin margins.

Third, notionally, the world is still playing by a free trade rule-book, even as richer countries flaunt it openly. For instance, India’s National Solar Mission required domestically produced panels. The US challenged this at the WTO, which ruled against India. Similar rulings struck down Brazil’s auto incentives. This can fracture attempts to climb up the value chain.

Fourth, domestic capacity and politics. Building a green industrial base needs institutions that can design policies, adjust when they fail, and stay the course across elections. And through all this, they must survive the very real political influence fossil fuel companies still have.

How do we break out?

The CSE recommends that governments treat green industrialisation as a central development project.

There’s an order that, it believes, we can pursue to make progress. They can create domestic demand through renewable targets and EV policies, or even public procurement. It can then use that demand to build production capacity. In between, subsidy schemes could reward learning, not just capacity installation.

An unavoidable part of this process, it believes, is to engage with China. Here, the report urges being strategic. Developing countries do have some leverage, should they choose to use it. Indonesia required Chinese investors to set up local facilities. Brazil pushed BYD for an R&D centre and localisation targets.

And it suggests developing countries collectively push for a “climate waiver” at the WTO — allowing more space for local content rules and targeted subsidies in green sectors. Unless the green transition gives them the tools to industrialise, they will never buy into the transition.

The bottom line

The shift to low-emission technologies is going to reorganise global industry anyway. If countries like India don’t actively build their own role in making those technologies, they risk locking themselves into a weak position: exporting cheap raw materials, importing high-value equipment, and absorbing the worst climate impacts.

Avoiding this will take deliberate choices at home and a hard push to change global rules. Whether the political will exists, however, is an open question.

Tidbits

SEBI to ban use of live market data in investor education

SEBI will amend its rules to stop educators and finfluencers from using current live market data in tutorials, allowing only past data. This comes soon after the regulator ordered ₹546 crore disgorgement from finfluencer Avadhut Sathe. SEBI says too many investors rely on unverified online tips and need safer, more responsible content.

Source: NDTV Profit

TRAI rejects DoT push to raise satcom spectrum fee to 5%

TRAI has rejected the telecom department’s proposal to hike satellite players’ annual spectrum fee to 5% of AGR, sticking to its earlier recommendation of 4%. It warned that a higher fee would hurt rural and remote-area connectivity. TRAI also retained the ₹500 per-subscriber urban fee, while exempting rural users to bridge the digital divide.

Source: Business Standard

Trump hints at fresh tariffs on Indian rice as talks stall

U.S. President Donald Trump signaled new tariffs on Indian rice and Canadian fertilisers, saying imports are hurting American farmers as rice prices fall. India already faces a 50% tariff (up from 10%), but exports continue due to strong global demand. Trade talks with India and Canada remain slow, with no breakthrough expected soon.

Source: Business Standard

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Krishna.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Very nice article!! Cloudflare story was very good :D

One correction - Cloudflare is not a private company