What is happening to Mamaearth?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Mamaearth reported a 19 crore loss—what happened?

What’s driving the gold price rally?

How Campus, Bata, and Metro are Reshaping India's Footwear Industry

Mamaearth reported a 19 crore loss- what happened?

Mamaearth, one of India’s most popular beauty and personal care brands, recently reported a surprising loss of ₹19 crore. This is quite a change for a company that just last quarter was celebrating a ₹40 crore profit and has been known as a digital-first success story. The decline in revenue, which dropped by 7% year-on-year to ₹462 crore, adds to the growing concerns. So, what’s gone wrong for a brand that once seemed unstoppable?

To understand what’s happening, we need to look back at Mamaearth’s journey. The brand started out online, finding early success on platforms like Amazon and Flipkart, where more and more Indian consumers were shopping. Mamaearth wasn’t the only brand to take this approach—many beauty brands were embracing a “direct-to-consumer” (D2C) model. In simple terms, this meant reaching customers directly through online channels and skipping the traditional retail route. For a while, this approach worked very well. It was efficient, and digital ads helped brands build strong identities without the big expenses of traditional advertising.

However, as more beauty brands joined the online space, competition heated up. Mamaearth suddenly found itself competing with many others for the same pool of online shoppers, making it difficult to stand out. Realizing it needed to expand beyond its online roots, Mamaearth decided to take a big step—it chose to go offline.

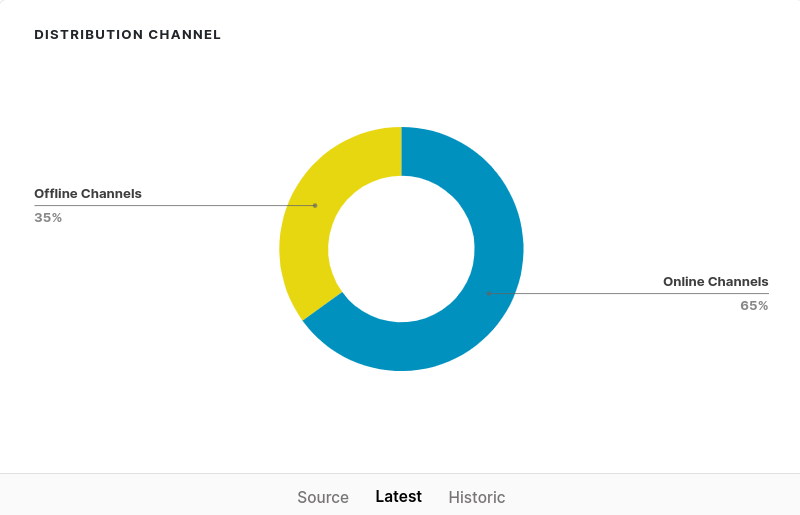

Today, around 35% of Mamaearth’s products are sold through physical stores. Moving offline helped the brand reach more people, especially those less comfortable with online shopping, giving it a wider presence across India. But this shift brought its own challenges. Unlike online sales, where every purchase can be easily tracked and adjustments made quickly, selling through physical stores adds a layer of complexity. There’s a need to manage logistics—moving products across various regions, keeping track of inventory at multiple stores, and building relationships with a network of retailers. Initially, Mamaearth handled this transition by partnering with “super-stockists.”

These super-stockists are large distributors who buy products in bulk from the brand and then distribute them to smaller retailers across the country. This helped Mamaearth quickly get its products into stores across India, but it also created a challenge. Unlike online sales, where Mamaearth could monitor inventory in real-time, relying on super-stockists made it hard to see exactly how products were moving at each store. Without this detailed information, the brand had less control over stock levels in different regions, leading to an unexpected issue—piles of unsold products.

According to reports from the All India Consumer Products Distributors Federation, which represents distributors, over 2,000 distributors were stuck with large amounts of unsold stock, including products nearing expiration. Distributors blamed Mamaearth for not replacing these expired items in a timely manner. Although Mamaearth denied this, it did admit that it needed to improve its inventory management and control.

To address these issues, Mamaearth launched a project called “Project Neev.” This project aimed to replace super-stockists with smaller, direct distributors in major cities, giving the brand closer control over inventory and better sales data. With these new distributors, Mamaearth hopes to track its products more closely, making its supply chain smoother and more responsive.

However, things didn’t go as planned. During the transition, the new distributors ended up with too many unsold products. This forced Mamaearth to write off ₹63 crore worth of expired inventory—products that couldn’t be sold. This write-off wasn’t just a huge financial setback; it also pointed to a deeper issue. When a company has to discard a large amount of inventory, it usually signals problems with demand forecasting—the process of predicting how much of each product customers will actually buy.

Mamaearth’s forecasting troubles were likely worsened by its rapid expansion into new products. In 2022 alone, the brand introduced 122 new products—double the average for the beauty industry. Most consumer goods companies focus on a few core or “hero” products that reliably drive sales. But instead of concentrating on its top sellers, Mamaearth kept rolling out new products, which stretched its resources thin and made inventory management even harder. Recently, Mamaearth’s CEO, Varun Alagh, acknowledged the need to put more emphasis on these hero products moving forward.

On top of these challenges, Mamaearth has been spending a large part of its revenue on marketing. Around 35-42% of its earnings go towards influencer partnerships, digital ads, and social media campaigns—higher than the industry average. While this approach worked well for building the brand online, it hasn’t had the same impact offline. In physical stores, customers tend to rely more on what they see on the shelves or recommendations from store staff, rather than social media ads. This gap has raised questions about whether Mamaearth’s high marketing spend is sustainable, especially given the company’s recent financial pressures.

The Mamaearth story highlights the challenges of moving from a digital-first brand to an omnichannel one, meaning it operates both online and offline. While its online growth showed promise, the move to physical stores exposed weaknesses in its supply chain, product strategy, and marketing approach. To move forward, Mamaearth needs to focus on building a more sustainable business model—one that prioritizes a few key products, tightens up inventory management, and adapts its marketing strategy to fit offline customers better.

Mamaearth’s journey shows that rapid growth can be thrilling but also requires a solid foundation. Now, the company faces the challenge of addressing these issues quickly if it hopes to regain its momentum. Whether Mamaearth can adapt fast enough will determine if it can bounce back or if its offline expansion will continue to be a tough climb.

What’s driving the gold price rally?

Lately, gold has been making headlines again, with prices surging to new highs in October. For an asset known for its stability, that’s no small feat. But the real question is—what’s driving these prices up, and why has gold suddenly become more valuable?

Most of you watching or listening probably know that gold is often seen as a “safe haven” investment. When things in the world feel uncertain—whether due to political, economic, or social reasons—people tend to put their money into gold, trusting it to hold steady even when other investments don’t.

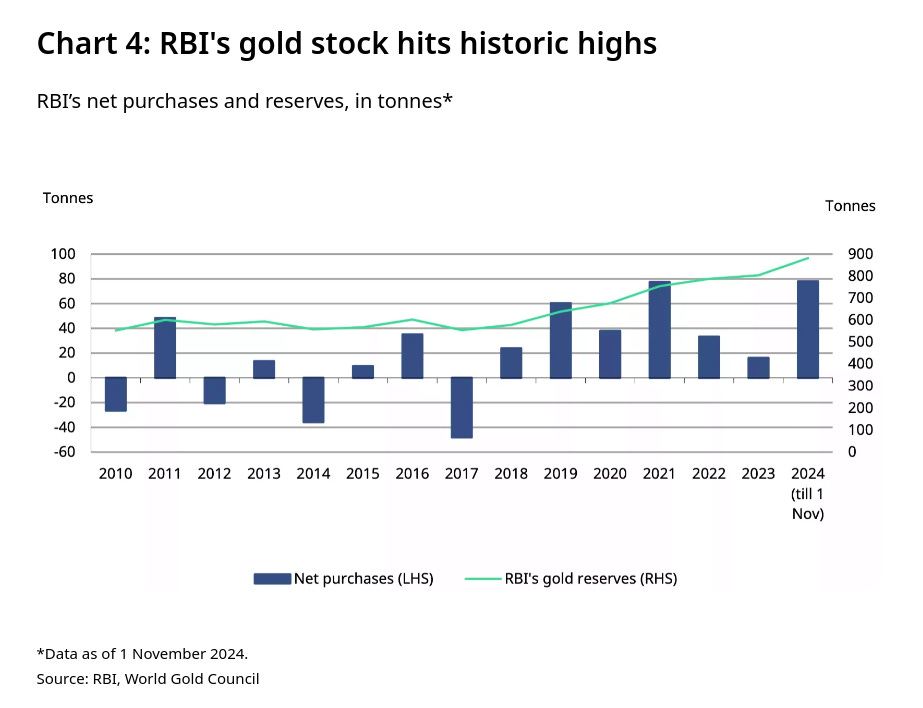

Right now, we’re seeing what almost feels like a “perfect storm” of global uncertainty. There are multiple ongoing conflicts around the world, and until recently, there was a lot of uncertainty around the U.S. elections. Because of this, central banks across the globe, including India’s RBI, have been buying gold at a record pace.

Take the RBI, for example—it has added a massive 78 tonnes to its reserves this year. To put that in perspective, it’s the second-highest level of gold buying in the RBI’s history.

When central banks buy gold in such large amounts, it sends a clear message to the broader market that gold is a valuable asset, especially during turbulent times like these.

Now, typically, when gold prices climb, people tend to hold back from buying it—because, of course, it’s more expensive. But in India, surprisingly, the demand for gold has stayed strong. This Diwali season saw great sales for gold. People continued investing in the metal through jewellery, coins, and gold bars, despite the high prices.

What’s even more interesting is that jewellers are taking note of this trend. Titan Company, which owns Tanishq, has seen a rise in demand since July, particularly for wedding-related jewellery. This increase also coincides with the government’s recent decision to cut import duties on gold, making it cheaper to bring into the country. This price adjustment brought buyers back into the market, especially those looking to make big purchases like wedding jewellery.

PNG Jewellers, another major brand, noticed an interesting trend during Diwali. Their sales grew by around 7-8% in terms of volume—the actual amount of gold sold. But in terms of value, their sales saw a remarkable jump of 35-40% compared to last year. This difference shows that people are not just buying jewellery but are also investing in pure gold, like coins or bars, which are more straightforward as investment assets.

This shift towards pure gold investment might be influenced by the government ending the gold sovereign bond scheme—a popular option for people to invest in gold without actually owning it physically. With that scheme no longer available, people have fewer non-physical investment choices for gold, which is likely driving them to buy gold directly.

On the supply side, India’s gold imports have surged thanks to the import duty cut in July. In October alone, official gold imports were valued at ₹59,236 crore, a big jump from ₹36,482 crore in September. Monthly imports are now at around 95 tonnes, almost double what we saw earlier this year. This increase has also helped clean up the market by reducing black market activity, pushing more of the trade into official, transparent channels, which benefits both consumers and jewellers.

Another noteworthy trend is the rise in Gold ETFs or Exchange-Traded Funds. A Gold ETF lets people invest in gold without actually holding it physically. Instead, these funds track the price of gold, making it easier for people to benefit from price changes without dealing with the hassle of storage or security concerns.

In October, Gold ETFs in India saw record inflows of ₹1,960 crore, pushing the total assets in these funds to a new high of ₹44,500 crore. This year alone, Indian Gold ETFs added 12.2 tonnes—a 32% increase from last year. This trend highlights a change in how people view gold—not just as jewellery but also as a valuable investment tool that can be accessed easily through ETFs.

Interestingly, fewer people are trading in their old jewellery for new pieces. For example, Tanishq has reported a drop in the number of customers exchanging old jewellery, about 3% lower than usual. This suggests that with gold prices so high, people might prefer to hold onto their gold instead of trading it in for something new.

In the past, jewellers often offered discounts on “making charges” to attract customers. But this year, some major brands, including Tanishq, have changed their strategy by offering discounts on the gold price itself. This shift shows just how competitive the market has become, with big jewellers trying to match the aggressive pricing of smaller, local shops.

Looking ahead, jewellers are feeling hopeful about the wedding season, which runs from November to March in India. With several auspicious dates on the calendar, the expectation is for strong demand for wedding jewellery.

How Campus, Bata, and Metro are reshaping India's footwear industry

In today’s story, let’s dive into India’s footwear industry. It’s a market that doesn’t always get a lot of attention, but right now, it’s going through some big changes. And that’s exactly what we’re going to talk about—what’s happening and why it matters to all of us.

India’s footwear market is currently valued at around ₹1 lakh crore, and it’s growing fast. One big reason is that footwear isn’t just about having one pair of shoes anymore. These days, people are buying multiple pairs for different needs—workouts, office wear, casual weekends, and more. So, this idea of “more pairs per person” is really driving the market’s growth.

But it’s not just about owning more shoes. People are also becoming pickier about where their shoes come from. The days when many of us were okay with buying cheap, no-brand shoes from local stores are fading. Instead, more people are choosing branded, high-quality shoes.

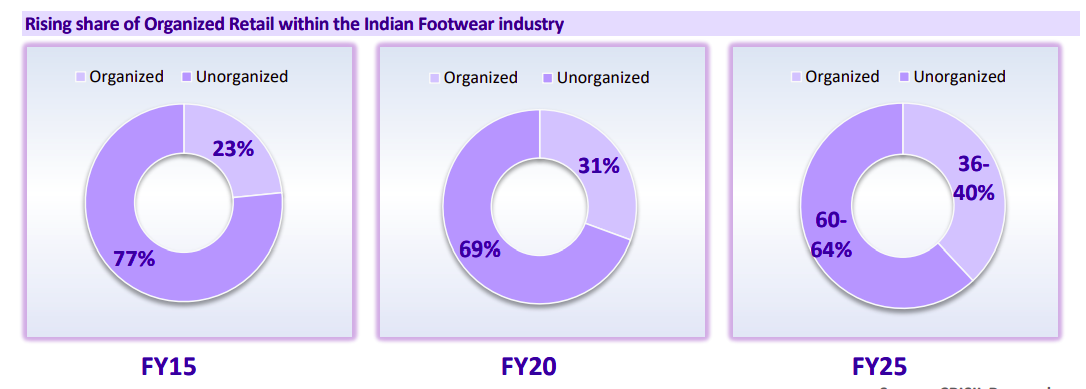

Let’s put some numbers behind this shift. About ten years ago, big and popular brands made up only about 23% of the market. But today, they hold a huge 36%! This move toward well-known brands is important because it shows what people want—quality, durability, and shoes that look and feel great.

But the big question is—why is this happening? Why are people turning to better brands for their shoes today?

There are three major factors behind this shift, and here’s what they are:

First, there’s the rise of athleisure. Athleisure is one of the biggest trends in the apparel market today, blending athletic wear with everyday casual outfits. In footwear, you can think of it as sneakers that are perfect for a workout but also work great for a casual outing. You’ve probably noticed how sneakers are everywhere these days—at gyms, cafes, and even in offices (I’m one of those people who wears them to work!). This isn’t just happening in India; it’s a global trend!

And the athleisure market isn’t slowing down anytime soon. Analysts expect it to grow by about 15% every year until 2025, eventually making up more than 20% of the entire footwear market. So, if you see even more people rocking sneakers in the coming years, now you know why!

The next trend is about premiumisation, which simply means shoes are becoming more than just something you wear for function—they’re turning into style statements. People are now more willing to spend a little extra on high-quality, stylish shoes that reflect their personality.

Take Bata, for example. Most of us have probably owned a pair of Bata shoes at some point in our lives. They’ve long been known for their affordable, everyday shoes. But in recent years, they’ve been putting more focus on their premium lines, especially with brands like Hush Puppies. By emphasizing quality and style, Bata is trying to appeal to consumers who want more than just basic footwear. They’ve even introduced a “Sneaker Studio” line and partnered with international brands to keep up with the growing demand for fashionable options.

Metro Brands has taken a similar approach, with about 85% of their sales coming from shoes priced above ₹1,500. While that price range might not seem “premium” globally, in India, it’s considered mid-to-premium. This shift towards higher-end products has helped Metro increase its profits, as they can charge a bit more for high-quality shoes.

So, why are people willing to pay extra? Rising incomes play a big role here. With more disposable income than before, people are choosing to invest in shoes that are both stylish and long-lasting. This premium segment is also more profitable for brands, making it a win-win situation.

The third big trend shaping India’s footwear industry is distribution. India is a vast country with a diverse population, and reaching all those customers isn’t easy. To tackle this, brands are using a mix of online and offline strategies to ensure their products are widely available.

Relaxo Footwear, for instance, isn’t focused on premium products. Instead, they’ve built a massive network of 70,000 retail touchpoints, from big cities to small towns. This wide reach gives Relaxo a unique advantage in terms of accessibility.

Meanwhile, brands like Campus and Bata are focusing heavily on e-commerce. A large portion of their sales now comes from online platforms, which is great for targeting younger, tech-savvy shoppers. Campus, for example, doesn’t need a physical store in every city—they can reach customers all over the country through online channels.

But offline stores are still important, especially in smaller cities where people prefer to shop in person. Bata, for instance, is expanding its network of franchise stores to reach these areas. By 2025, online footwear sales are expected to grow from 16% to 22% of the market, showing that having both an online and offline presence is key to staying competitive.

So, if you’ve noticed more people wearing branded sneakers or stylish shoes, these trends probably explain why. India’s footwear industry is growing fast, and the strategies these brands are using will likely shape the market for years to come. Whether you’re an industry analyst or simply interested in business trends, this is definitely a sector worth watching.

Tidbits:

India plans to cut laptop and IT hardware imports by 5% under the "Make in India" and PLI schemes, aiming to boost domestic manufacturing and reduce reliance on China. An import management system for seven IT hardware items will stay active until December 31 to ensure there are no supply disruptions during this transition.

The adoption of CNG in sedans has surged, making up 41.5% of sales in 2024, compared to just 10.8% in 2021. This shift is driven by cost-conscious buyers. However, while the overall market share of sedans fell to 8.3%, SUVs have soared to 53.56%. As a result, manufacturers are repositioning sedans to target niche markets.

India's smartphone exports reached $2 billion in October 2024, marking a 70% year-on-year increase, largely driven by Apple and Samsung. If this trend continues, exports in FY25 could hit $18–20 billion, strengthening India’s role as a major global manufacturing hub.

Tata Electronics has acquired a 60% stake in Pegatron’s Tamil Nadu iPhone plant, further boosting its role in Apple’s supply chain. India’s iPhone production is expected to account for 20-25% of global shipments in 2024, up from 12-14% in 2023.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉 Join the discussion on today’s edition here.

Great job! I found this blog/YT channel a month ago and I've been reading every day since.

Do you have a research team finding topics to write about? Because the snippet about Mamaearth and footwear industry is not info that can be found unless you dig it up.

Great great job. Love it!

What have I understood from recent articles on daily brief is that India is seeing a K shaped growth wherein the upper middle class is striving for premiumisation and better quality products while the middle and lower middle class are struggling with falling disposable incomes due to inflation and weaker wage growth.