We’re entering a New Era of Global Finance

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Global Financial System Transformation

A look at the plastics and pipes industry

Global Financial System Transformation

Today, we're diving into something that's quietly reshaping the entire global financial landscape. It's a story that affects every investment decision, every currency trade, and economic policy decision being made around the world right now.

The Great Financial Transformation

In the recent BIS Annual Economic Report, the Bank for International Settlements—think of them as the central bank for central banks—had a fascinating chapter on the structural transformation of the global financial system. And when I say transformation, I mean we're talking about changes so fundamental that they're rewriting the rules of how money flows around the world.

So what exactly has changed? Well, imagine the global financial system as a massive highway network. For decades, the main routes were dominated by traditional banks lending to businesses and consumers. But since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, we've seen two seismic shifts that have completely altered this landscape.

First, global investors have fundamentally shifted their focus away from lending to private companies and individuals toward financing governments. Instead of funding businesses and consumers, these massive institutional investors are now primarily buying government bonds. The numbers here are staggering.

Since the Great Financial Crisis, claims on governments have gradually become the main driver of overall credit growth, overtaking credit to the private sector. Government bond issuance has grown at a considerably faster pace than both loans and corporate bond markets. While private sector lending has grown modestly, government bond markets have exploded in size, fueled by massive fiscal deficits and, of course, the pandemic-era spending spree.

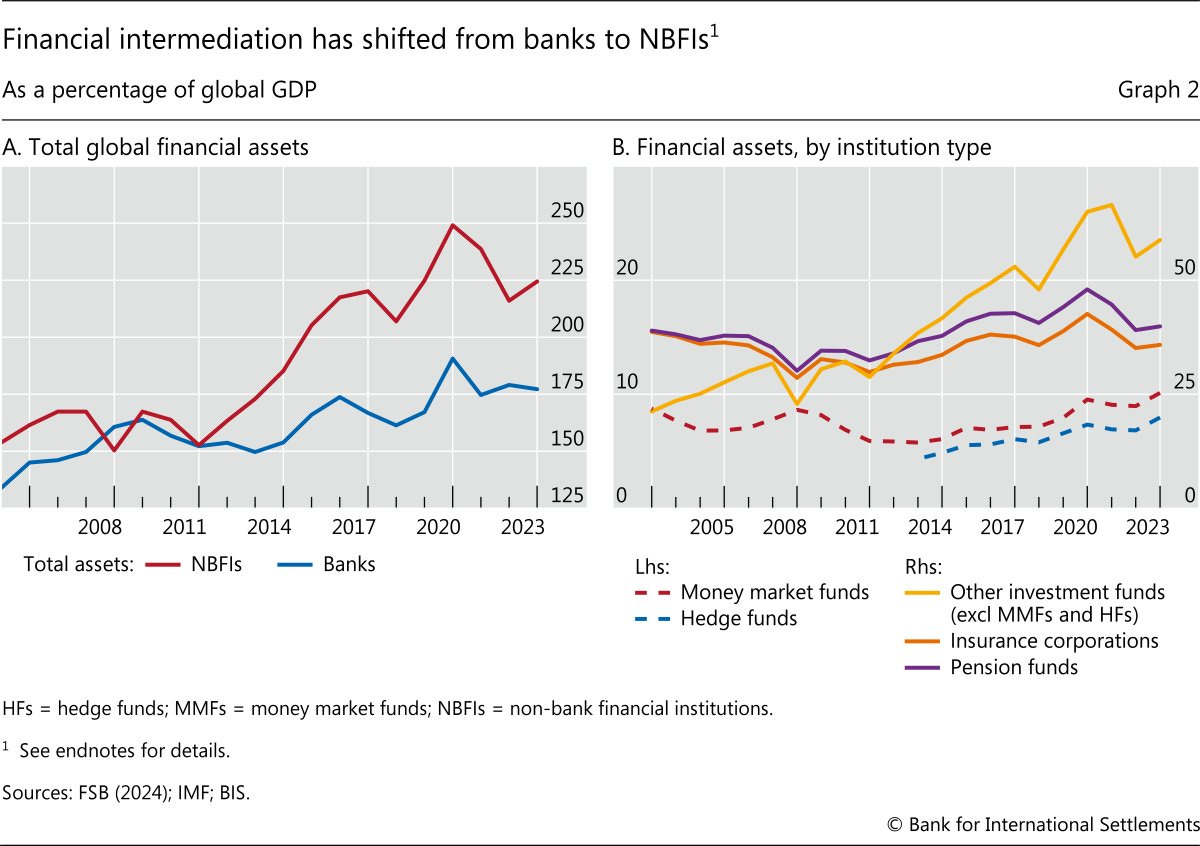

The second major change? Non-bank financial institutions have become the new titans of global finance. Now, when I say "non-bank financial institutions," I'm talking about pension funds, insurance companies, asset managers, and hedge funds. These aren't your traditional neighborhood banks. These are massive institutional investors managing trillions of dollars, and their total assets have grown from 167% to 224% of global GDP between 2009 and 2023. Meanwhile, traditional banks? They've grown much more modestly, from 164% to just 177% of global GDP over the same period.

The Implications: A New Financial Reality

Now, you might be thinking, "Okay, so what? Different players, same game, right?" Wrong. This transformation has created an entirely new financial reality with profound implications that reach far beyond Wall Street.

Here's the thing: when banks were the dominant players, they primarily operated within their home countries. Sure, some big banks had international operations, but the bulk of lending was domestic. Financial conditions moved relatively predictably within national borders. A central bank could adjust interest rates, and the effects would ripple through the domestic banking system in fairly contained ways. Think of it like ripples in separate ponds.

But these new players? They're fundamentally different beasts. A European pension fund doesn't just invest in European assets—they're actively hunting for yield across the globe, buying U.S. Treasuries, Japanese bonds, emerging market debt, you name it. And here's what makes this transformation so significant: these institutions manage absolutely enormous pools of capital. We're talking about pension funds and insurance companies with hundreds of billions under management.

This global reach has fundamentally changed how financial shocks transmit across borders. Remember, these aren't just passive buy-and-hold investors. When risk appetite changes—say, when investors suddenly become worried about inflation or geopolitical tensions—these massive funds can shift billions of dollars between countries and asset classes almost instantaneously.

The result? Instead of those separate financial ponds with occasional spillovers, we now have a vast, interconnected ocean where a storm in one region can create waves that crash on shores thousands of miles away. A decision made by a fund manager in London can instantly affect bond markets in Tokyo, currency values in São Paulo, and borrowing costs for companies in New York.

But here's what's really remarkable: this isn't just about size and speed. The BIS research shows that this new system has made financial markets much more sensitive to changes in what they call "risk factors" – essentially, how willing investors are to take on risk at any given moment. When global risk appetite shifts, it now moves through the entire system.

The financial world has become dramatically more connected, and that connectivity is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it means capital can flow more efficiently to where it's needed most. On the other hand, it means that financial stress can spread faster and more broadly than ever before.

The FX Swap Revolution

Now, this is where the story gets really interesting, because none of this global investment activity would be possible without a financial instrument that most people have never heard of but that has become absolutely crucial to the modern financial system: the FX swap.

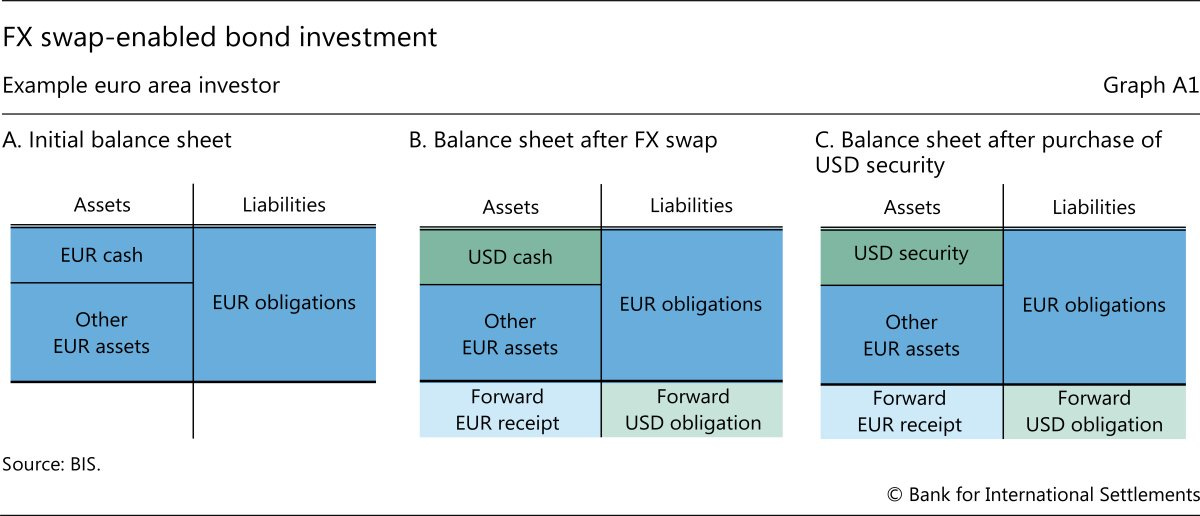

Let me break this down with a simple example. Imagine you're a European pension fund with obligations to pay retirees in euros, but you want to invest in U.S. Treasury bonds because they offer attractive yields. Here's your problem: if you buy those dollar-denominated bonds with euros, you're exposed to currency risk. What do I mean by currency risk? Well, if the dollar weakens against the euro, your investment could lose money even if the bond itself performs well.

Enter the FX swap. It's essentially a financial contract that lets you have your cake and eat it too. You can invest in that U.S. Treasury bond while hedging your currency risk. Here's how it works: You enter into an agreement where you exchange euros for dollars today at the current exchange rate, use those dollars to buy the bond, and simultaneously agree to exchange dollars back for euros at a predetermined rate when your investment matures.

It's like having a currency insurance policy. You get the upside of the foreign investment while protecting yourself from exchange rate movements. So if that U.S. Treasury pays 5%, you can lock in a known return in euro terms, regardless of what happens to currency exchange rates.

Now here's the kicker—the FX swap market has become absolutely massive. We're talking about $111 trillion in outstanding contracts by the end of 2024. To put that in perspective, that's larger than the entire global stock of cross-border bank credit and international bonds combined. And roughly 90% of these swaps have the U.S. dollar on one side, which tells you just how central the dollar remains to global finance. What's particularly interesting is that the fastest-growing segment has been contracts with non-bank financial institutions—they've nearly tripled in size since 2009.

But here's something that might surprise you: over three-quarters of all these FX swap contracts have a maturity of less than one year. That means this massive market is constantly rolling over, creating a dynamic that can amplify both stability and volatility in global markets.

Global Implications for Financial Conditions

So what does all this mean for financial conditions around the world? Now, when I say "financial conditions," I'm talking about how easy and expensive it is for businesses, governments, and individuals to borrow money and access credit. This is where the story takes a fascinating turn, because we're seeing something that challenges conventional wisdom about monetary policy and financial markets.

Traditionally, we thought of financial conditions as primarily domestic affairs. The Federal Reserve sets interest rates, and that mainly affects U.S. financial conditions. The European Central Bank makes policy, and that mainly affects European markets. Simple, right?

But this new globally interconnected system has turned that logic on its head. The BIS research shows something remarkable: financial conditions are now transmitted across borders much more strongly than before, and this transmission flows in multiple directions now, not just from the U.S. outward.

What do I mean by that? Well, it used to be that when the Federal Reserve sneezed, the rest of the world caught a cold. U.S. monetary policy was the primary driver of global financial conditions. But now? U.S. financial conditions are increasingly affected by developments in other advanced economies too. It's become a two-way street, or really, a multi-lane highway with traffic flowing in all directions.

Let me give you a concrete example from the report. Remember the yen carry trade that made headlines in August 2024? Japanese investors had been borrowing cheaply in yen and investing in higher-yielding assets elsewhere. When that trade unwound suddenly, it didn't just affect Japanese markets – it transmitted financial stress directly to the United States, demonstrating how interconnected these systems have become.

And here's another striking finding: the BIS research shows that the cross-country co-movement of government bond yields and corporate spreads has increased significantly in recent years. When we look at financial market connectedness measures – essentially how much of market movements can be explained by transmission across countries rather than domestic factors – we see that over 60% of risk factor variability could be explained by global connectedness during the pandemic. That's up from below 50% during the Great Financial Crisis.

What's even more fascinating is that foreign private sector investors—mainly these non-bank institutions – now hold more than half of all foreign holdings of U.S. Treasuries. Think about that: the world's most important bond market is increasingly in the hands of global asset managers, not just foreign governments.

But here's what's really important for anyone trying to understand where markets are headed: this interconnectedness means that domestic monetary policy has become more complex, but it hasn't become powerless. The research shows that while external factors now have a significant effect on financial conditions, domestic monetary policy still retains strong influence, especially over government bond yield curves.

What this means in practical terms is that central banks can still steer their domestic financial conditions, but they now have to be much more aware of what's happening globally. They can't just set policy in isolation—they need to consider how their decisions will reverberate through this interconnected web and how foreign developments might affect their domestic objectives.

This creates both challenges and opportunities. On one hand, it's harder for central banks to achieve their desired financial conditions when global forces are pulling in different directions. On the other hand, this connectivity means that coordinated central bank actions can be more powerful than ever.

The report also reveals something crucial about monetary policy effectiveness: while global spillovers have become more powerful, domestic monetary policy hasn't lost its punch. When central banks adjust policy rates, they still have significant effects on domestic government bond yields—often exceeding the spillover effects from abroad. But here's the catch: risky assets like stocks are now more heavily influenced by global conditions than domestic policy, especially in emerging markets.

Closing Thoughts

We're living through a fundamental transformation of how global finance works. The old model of largely separate national financial systems has given way to a highly interconnected network driven by massive institutional investors using sophisticated hedging strategies.

A look at the plastics and pipes industry

We came across this report from Motilal about the plastics and pipes industry, and since we have never really covered this industry, we thought now would be a good time to look at it.

Like many sectors in India, it’s moving from an unorganised, hyper-local setup to one that’s more brand-led, formal, and quality-driven. It’s changing how homes are built, how water reaches your tap, how farms get irrigated, and how cities lay down their sewage systems.

Now here’s the key bit: most Indian pipe companies don’t control this entire chain. They usually buy resin either from domestic suppliers like Reliance and Chemplast Sanmar, or import it. Only Finolex Industries is fully backward-integrated—they make their own VCM and PVC resin. That gives them more control over cost and supply.

But others—like Supreme and Prince—focus only on the mid-to-downstream segments: compounding, molding, branding, and distribution.

And that’s why resin prices matter so much. When crude oil prices spike or supply chains get disrupted, resin prices go up. Companies either pass on the cost to customers or absorb the hit. But there’s often a lag—especially in agriculture or infrastructure—where you can’t immediately hike prices. That lag squeezes margins. And when resin prices crash, companies holding expensive inventory take a hit. So the industry’s profitability is tightly linked to resin price cycles.

What kinds of pipes are used?

The Indian plastic pipes industry is dominated by four main types:

Unplasticized PVC (64–65% of demand): Used in irrigation, cold water plumbing, and drainage. It’s cheap, easy to install, and corrosion-resistant—making it the go-to for agri and rural use.

Chlorinated PVC (15–16%): Handles hot water, lasts longer, and is used in residential and commercial plumbing. Costlier than UPVC but offers better margins.

HDPE (15%): Used in underground drainage and infrastructure. It’s flexible, strong, and long-lasting—ideal for cities and public utilities.

PPR (4–5%): A premium pipe for hot/cold water in high-end or industrial setups. Durable but needs specialised installation, so adoption is limited.

In short, UPVC drives volume, CPVC drives margins, HDPE is infra-focused, and PPR is niche. Most companies try to balance these to optimise both scale and profitability.

Where’s the demand coming from?

The biggest chunk—around 45%—comes from irrigation in agriculture. Indian farms are shifting away from open canal irrigation to more efficient drip and sprinkler systems, and that shift needs pipes.

The second-largest segment is real estate and plumbing, which makes up about 39%. Every home, building, and office needs drainage systems, plumbing, and hot-cold water lines. As urban India grows, so does this segment. Sewerage and infrastructure projects like underground drains account for another 12%, and the rest comes from miscellaneous uses.

What’s interesting is that even when new construction slows down, the industry still sees steady demand—because a 30% of the market is still driven by replacements.

Older GI (galvanised iron) pipes rust. Even some older PVC installations degrade over time. So, whether or not you’re building something new, repairs and upgrades keep the volumes flowing.

A huge part of the growth in plastic pipes isn’t just coming from homes or farms—it’s coming from the govt. In the past few years, the Indian government has launched massive infrastructure programs that require millions of meters of piping. The Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM), for instance, aims to provide functional tap water to every rural household by 2028. As of now, 81% of homes have been covered, but over 37 million households still need to be connected. That last leg alone can drive enormous pipe demand over the next 2–3 years.

Then there’s PMAY, the affordable housing scheme targeting 49.5 million pucca homes, and AMRUT, which is modernising urban water and sewerage systems in hundreds of cities. Add to that Namami Gange and Smart Cities, and you get a scale of public sector demand that’s hard to ignore.

Even on the agri side, the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchai Yojana (PMKSY)—focused on irrigation—saw a 25% budget hike this year, with ₹8,300 crore earmarked for micro-irrigation and water use efficiency. And this matters, because despite progress, nearly 48% of India’s cultivated land is still rain-dependent. Bringing these areas under drip or sprinkler irrigation means one thing: more pipes.

Put simply, government money is pouring into water, sanitation, and irrigation. And almost all of that flows through plastic pipes.

Now, this entire shift is built on the rise of plastic pipes. A couple of decades ago, India relied heavily on metal pipes—steel or GI. These were bulky, expensive, prone to rust, and difficult to transport. Plastic pipes—PVC, CPVC, HDPE—changed all that. They’re cheaper, lighter, last longer, and don’t corrode. For a country like India, where infrastructure has to grow quickly and affordably, this shift has been massive.

To give you a sense of scale, the core plastic pipes market is already worth over ₹54,000 crore as of FY24. And it’s expected to grow at 14% annually, potentially crossing ₹80,000 crore by FY27. But that’s just the pipes. If you include adjacent categories—like water tanks, bathware, adhesives, paints, and packaging films—the total addressable market balloons to ₹2.72 lakh crore.

Now, here’s what makes this space even more fascinating.

The industry is consolidating

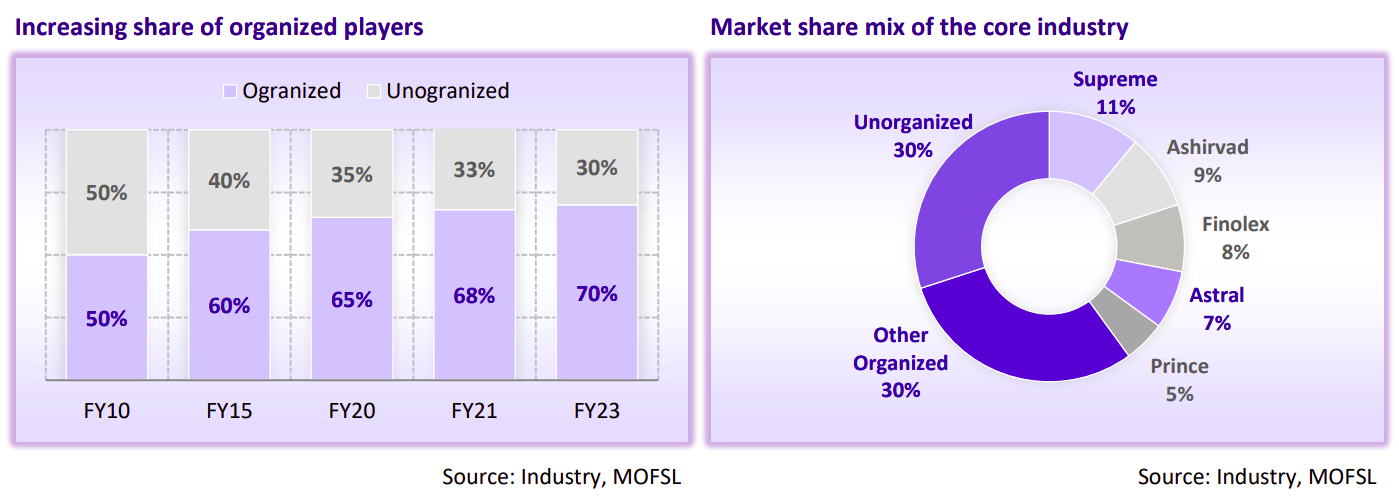

This was once an extremely fragmented market, dominated by hundreds of small, local manufacturers. These players mostly made basic agricultural pipes, sold within a limited region, with little focus on branding or product innovation. Margins were thin and operations were informal.

But over the last 10-15 years, that’s been changing fast. Today, the organised segment accounts for about 70% of the industry, up from just 50% a decade ago. The top five companies control roughly 40% of the total market. And the reason is simple: larger players offer consistent quality, better warranties, more variety—and importantly, better reach.

And there’s another tailwind for the big players: trade protection.

In 2020, the Indian government imposed something called an anti-dumping duty—basically a penalty tax—on CPVC compounds imported from China and South Korea. These compounds are a key raw material used to make hot water pipes. The idea was to stop cheap imports from undercutting domestic manufacturers. That duty was supposed to last five years, but the government recently extended it till 2029.

Now, most small, unorganised players in India don’t make their own CPVC compounds—they import them. So this duty makes their raw materials more expensive. Big players like Astral or Prince Pipes, who either make their own compounds or have reliable local tie-ups, aren’t affected as much. That gives them a pricing and margin edge.

There’s also talk of a similar anti-dumping duty being added on PVC resin—another core input for regular pipes. If that happens, it’ll hit import-reliant players even harder.

In short, government policy is quietly tilting the playing field in favour of large, well-integrated domestic brands. It’s becoming harder and costlier for small players to compete.

Since pipes are bulky and expensive to move, having manufacturing plants near demand hubs is crucial. That’s why most top companies now have multiple factories spread across India.

Who are the big players?

Let’s start with Supreme Industries. They’re one of the oldest, most diversified, and biggest names in the sector. Their product range covers everything—PVC, CPVC, HDPE, PPR pipes, fittings, valves, tanks, and even plastic furniture. With nearly 30 manufacturing plants and a deep distribution network, they lead the industry in both value and volume.

Astral is best known for premium CPVC pipes used in hot water systems. They were early movers in this segment, have built a strong brand around quality, and also diversified into adhesives and sealants. They’re arguably the most profitable player in the space, with the highest margins per kilo sold.

Then there’s Finolex Industries, a strong player in agri pipes. What sets them apart is their fully backward-integrated model—they manufacture their own resin, starting from VCM, giving them an edge in cost control and supply security. Their distribution is deeply entrenched in rural and semi-urban India.

Prince Pipes is a relatively newer entrant but growing rapidly. They’ve built a wide product range, tied up with global leader Lubrizol for CPVC compounds, and invested heavily in branding and plumber outreach. They’re the fast challenger in the space.

Each of these companies has carved out a niche—Supreme leads in volume and diversification, Astral dominates CPVC and fittings, Finolex is strong in agri, and Prince is making inroads into plumbing and bathware. But there’s another question that needs answering.

Who actually picks the pipe brand?

Most of us don’t. The decision is usually made by the plumber, contractor, or architect—people who understand technical specs, have hands-on experience, and maintain relationships with local dealers. That’s why pipe companies focus heavily on plumber loyalty programs.

Astral has a dedicated loyalty app. Prince’s ‘Udaan’ program has over 1.6 lakh plumbers enrolled, rewarding them with points, cashback, and even trips. The idea is simple: if the plumber trusts your brand, he’ll push it.

So what do we have here?

A high-growth industry with a long runway. Strong tailwinds from agriculture, urbanisation, and replacement demand. A shift from unorganised to organised. Clear leaders with distinct strategies. And steady expansion—both in product range and distribution reach.

Every new home built, every farm that switches to drip irrigation, every old pipe replaced—that’s another few metres of plastic pipe sold. And increasingly, it’s coming from one of a handful of formal players who’ve turned this once-fragmented industry into a consolidated, brand-driven business.

Tidbits

Apollo Hospitals to Spin Off Digital and Pharmacy Units into ₹16,300 Cr Entity

Source: Business Line

Apollo Hospitals Enterprise Ltd (AHEL) has approved the spin-off and separate listing of its digital health and pharmacy businesses, consolidating them into a new entity that will include Apollo 24/7, Apollo HealthCo’s offline pharmacy distribution, Keimed Private Ltd’s wholesale pharma network, and AHEL’s telehealth services. The new company is projected to generate ₹16,300 crore in revenue for FY25, with a revenue run-rate target of ₹25,000 crore by FY27. AHEL shareholders will receive 195.2 shares of the new entity for every 100 AHEL shares held, while AHEL itself will retain a 15% stake and board representation. The listing is expected within 18–21 months. Additionally, the new entity plans to acquire a 74.5% stake in Apollo Medicals Pvt Ltd, which owns 100% of Apollo Pharmacies.

Reliance Defence–CMI JV Targets ₹20,000 Crore Defence MRO Market

Source: Mint

Reliance Defence Ltd, a 100% subsidiary of Reliance Infrastructure, has signed a joint venture agreement with US-based defence contractor Coastal Mechanics Inc. to enter India’s ₹20,000-crore defence MRO and upgrade segment. The JV will be established at Mihan in Maharashtra and will focus on the maintenance, repair, and modernization of over 100 Jaguar and 100 MiG-29 fighter aircraft, 20 Apache attack helicopters, and L-70 air defence guns. Reliance Defence aims to become one of the top three defence exporters from India. The company stated that the opportunity is driven by the Indian military’s shift from asset replacement to lifecycle extension and performance-based logistics. Market analysts noted that rising geopolitical risks may enhance export potential for Indian defence firms. The partnership also enables Reliance Defence to leverage CMI’s position as an authorized US defence contractor.

Hero Motors Files ₹1,200 Crore IPO, To Use Proceeds for Debt Reduction and Expansion

Source: Business Standard

Auto component maker Hero Motors has filed draft papers for an initial public offering (IPO) worth up to ₹1,200 crore. The IPO comprises a fresh issue of shares worth ₹800 crore and an offer for sale by existing shareholders amounting to ₹400 crore. According to the draft prospectus, proceeds from the fresh issue will be used to reduce debt and purchase equipment for facility expansion in Uttar Pradesh. Led by Pankaj Munjal, Hero Motors supplies to global clients including BMW and Ducati. The company is part of the Munjal family group that also runs Hero MotoCorp. ICICI Securities, JM Financial, and DAM Capital are acting as book running lead managers for the issue.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Bhuvan and Krishna.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

The way you have explained in simple and sober language is just amazing. waiting for more these types of breakdowns.

Just curious to know, why Apollo Pipes is not there in your second section?