Vedanta's ponzi allegation, China’s industrial obsession, GST still broken? | Who said What? S2E2

Hi folks, Welcome to another episode of Who Said What? I’m your host, Krishna. Thank you to everyone who shared feedback on the last episode. For those of you who are new here, let me quickly set the context for what this show is about.

The idea is that we will pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers and the likes and contextualise things around it. Now, some of these names might not be familiar, but trust me, they’re influential people, and what they say matters a lot because of their experience and background.

So I’ll make sure to bring a mix — some names you’ll know, some you’ll discover — and hopefully, it’ll give you a wide and useful perspective.

With that out of the way, let me get started.

Another Hindenburg event?

This week, a short seller named Viceroy Research called Vedanta Resources — the parent company of Vedanta Ltd, a “Ponzi scheme”.

Shorts sellers are investors who make money by betting on a company's stock price going down. They sell a stock for a high price, and if they get their bets right, they buy it back later at a lower price, pocketing the difference. They are kind of like the janitors of the stock market: they sweep up the mess in the market by identifying fraud and bringing some order to the chaos.

Now, let’s be clear: Since they are a short seller, they make money if Vedanta’s stock price falls. Just because they’ve published a research report doesn’t mean they’re right. They want people to believe Vedanta is in trouble, because that’s how their trade pays off. So take their claims with two buckets of salt. That said, sometimes short sellers shine a light where others aren’t looking.

Anyhow, what they’re saying about Vedanta, which is such a large company, is wild — and a very interesting saga. So I thought why not go through their claims.

Before I get into this, here’s something to keep in mind: Vedanata Resources Limited i.e VRL is the parent company of the listed company Vedanta Limited i.e. VEDL.

So, here’s what Viceroy calls a ponzi scheme: they say that Vedanta Resources — the parent entity — is feeding on its listed subsidiary just to stay alive. The key claim is this: Vedanta Resources forces its subsidiary to borrow money in order to pay it dividends. It uses those to pay off the interest on its own massive debt, that came from years of borrowing to fund acquisitions, projects and what not. But this, Viceroy claims, is self-destructive: the only valuable thing that Vedanta Resources owns is its shareholding in Vedanta Limited. But by feeding on it, it’s eating away at that very value.

How bad is it? Viceroy says that over the last 3 years, Vedanta Ltd generated around ₹46,000 crore less in cash than it paid out in dividends. It paid roughly ₹66,400 crore in dividends during that time — money it didn’t earn.

This is Viceroy’s main claim — and the biggest reason it suspects the company’s long-term health is in jeopardy. But there are other claims that Viceroy makes.

The one other thing that Vedanta Resources — the parent company — owns is the ‘Vedanta’ brand. VEDL and its group companies have paid ₹8,000 crore over 3 years in so-called “brand fees” to the parent company for using the "Vedanta" brand. But it asks: is this a genuine service that the parent company offers? Or is it just an arrangement to funnel money up the chain?

To be fair, though, this isn’t exactly unique. Many other conglomerates have similar arrangements, where a parent company earns by leasing its brand to many revenue-creating group companies.

Viceroy says the interest expenses of Vedanata Resources don’t add up. See, when you look at the books, it seems like Vedanta Resources is effectively paying interest of 15.8%. But the bonds it has issues, and the term loans it discloses, have an interest rate of around 9–11%.

So what's going on? Viceroy claims there’s some financial juggad behind the scenes. Maybe there’s hidden debt we don’t know about, or it’s using super short-term loans with sky-high interest — or maybe it’s just straight-up misreporting the numbers.

Viceroy also makes serious allegations against almost all of Vedanta’s subsidiaries. From a gold refinery in Dubai accused of laundering, to mines that are shut but still shown as active, to inflated asset values and unpaid revenues being booked — Vedanta makes a string of allegations against a variety of Vedanta operations. The only one it spares is BALCO — which it calls a “rare example of disciplined capital management”, and considers the exception that proves the rule.

Finally, Viceroy claims that Vedanta Resources has been pulling in money from the entire group, and using it to quietly tighten their grip over their money-making Indian subsidiary. In some cases, in fact, they claim that that money comes from VEDL itself! At one point, they claim, Vedanta Resources took a ₹7,900 crore loan from VEDL, in order to delist the company and take complete control of it. In essence, VEDL’s own money was being used to buy out its own shareholders. It claims that half of that loan is still unpaid.

Viceroy claims this was part of a larger playbook: repeatedly borrowing from group companies, using that money to increase control, and then quietly writing off the loans.

Now, as I said earlier, short sellers aren’t always the knights in shining armor they might seem to be. But they do perform an important role — of shining a light in places where people don’t usually look. It’s for investors to then decide if that light actually reveals anything. If you’re interested, we recommend that you read through the report, look through Vedanta’s own filings, and then see if the picture adds up to you.

Or you can just sit back with a bag of popcorn, and enjoy one hell of a corporate drama.

The case for never stopping production

Much like everyone else, we have found it impossible to ignore the developments in the Chinese economy. It’s pretty evident if you follow The Daily Brief.

So we listened to Lu Feng, who served in the Chinese State Planning Commission that formulated national economic plans and policies and he was also a director at Tsinghua University. In a recent interview, he made one bold statement after another. Here’s one:

“In the face of the US preparing for a full-on confrontation with China, China must not surrender – it must meet the challenge head on.”

How must it do that? By tapping into its ability to make things even further — and never giving up on it. He rejects accusations that China is flooding the world with its goods. China’s industrial prowess is as strategic to them as the dollar is to America.

Feng points to basic industry as what continues to power China’s growth. Stuff like steel, chemicals, and even simple finished goods. These must not be shut down, especially in favor of high-tech industries, as the latter can only be built with the former. China still has to convert 200 million rural residents into urban ones, and he says that basic industry is the pathway for that.

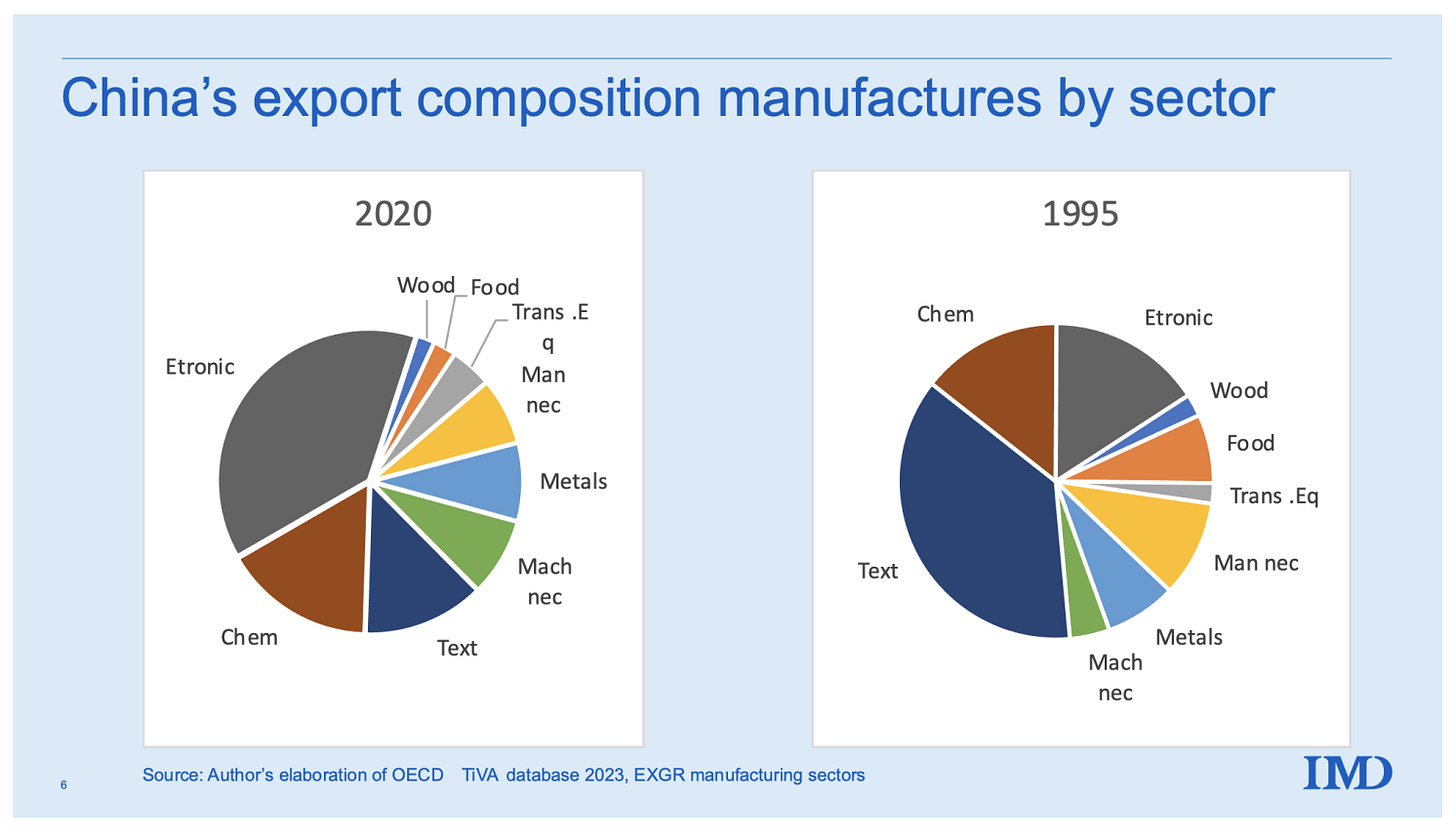

And it seems to be what China is doing. Despite some decline over time, labor-intensive manufacturing still constitutes 32% of China’s output. It is still the factory of the world, and no other country has been able to take over its role. All the while, it makes advancements in making semiconductors and AI.

Ironically, Feng draws lessons from the US’ mistakes. China’s early growth period resembles that of America. However, to stimulate growth again, America replaced its industry in favor of a financial base (like prioritizing Wall Street). It lost the ability to make things, while incurring high labor costs. Feng concludes:

“The historical truth is that America’s industrial decline was self-inflicted”.

Princeton researcher Kyle Chan (whose newsletter we highly recommend) calls this philosophy “Chinese industrial maximalism”. It basically refers to China’s strategy of pursuing large-scale, state-driven industrial development across many sectors simultaneously, aiming for dominance through sheer scale, speed, and coordination. Feng sees this as possible only because of a strong Chinese state that always prioritizes industry.

And this could make all the difference in the showdown between the superpowers.

The many problems with GST

GST is one of those weird regimes that has as many admirers as it has haters. On one hand, it stitched India’s many states into a single market, making it much easier to run a pan-India business. On the other, it’s hardly an elegant law — creating confusion and compliance issues of all kinds.

The government itself is aware of these gaps. In fact, a few months ago, the Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee called for an overhaul of the GST regime — asking for simpler compliance and procedures that are easier to work with.

Recently, the same call was echoed by Rajiv Memani, the President of the Confederation of Indian Industry. In a recent interview to MoneyControl, he said:

“I think it's time to do the 2.0 version of reform — more simplification particularly in the course of audits, more simplification in compliance.”

In essence, he thinks we’re past the time where concerns of implementation and adoption ate up the mindspace of policymakers. It’s now time to shift one’s attention to making it easier for businesses to interact with this system. To this extent, he pointed to several specific issues with how the GST system currently works. To start with, he says:

“The purpose for which GST was set up was really that there is uninterrupted credit transfer. To the extent those lines are getting broken — whether because of input tax credit issues or because some items are not being subsumed in GST…”

One of GST’s core promises was seamless input tax credit — if a businesses paid taxes on its inputs, it could claim credit for them while making a sale. In practice, though, this has broken down. From frequent rule changes, mismatches in invoices, to delays in vendor filings, claiming credits can be a nightmare. That’s what Memani is pointing to — if the “uninterrupted credit chain” is interrupted, suddenly, the GST becomes a lot less attractive as a tax regime.

There’s also a problem of rates. He says:

“...rationalization of rates — particularly for those products which go into mass consumption and benefit the 0 to 30% bottom income segment — I think that is very, very important.”

Today, we have a complex tax rate structure — with four-tiers (5%, 12%, 18%, 28%), along with a range of exemptions and cesses. Not only is all of this difficult to keep track of, it has also turned regressive, with the poorest households paying the most tax. This is what Memani thinks we need to avoid.

Finally, he talks about the weird audit structure under the GST that makes things extremely difficult:

“..if you're operating in five states, it doesn't mean you need to have five audits. You can have one audit and all the states can rely on that audit. We can have an unbiased process of identifying who that lead state is, and then it applies uniformly to this — and then after that, if there are investigations, they can happen. So I think the entire GST audit process has become very, very cumbersome, and I think that's something that we have to find a way to make more efficient."

Under GST, businesses are registered state-wise. Every registration is treated as a separate entity — so a company that works in many states could be subject to multiple audits, by different state tax authorities. This wastes companies’ time and effort. Memani argues for a single, simplified process.

This isn’t, of course, a comprehensive position paper on the issues with GST. But it’s a good sampler of the issues the regime has. Where the early years of the GST regime were spent in getting people to play along, Memani has a point: the coming years should be about taking their inputs to better it.

If you’ve made it this far, please let me know if you have any feedback for me 🙂

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.