Urban Company: Big IPO, Bigger Questions

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Understanding Urban Company

Bajaj Finance Q4 FY25: Great Results, But Sky-High Expectations

Understanding Urban Company

When Urban Company first launched (as “UrbanClap”) in 2014, it wanted to solve a basic but frustrating problem — how do you find a reliable plumber, beautician, or cleaner who actually shows up, does a good job, and charges fairly? Over the years, that simple idea has evolved into India’s largest full-stack home services platform. And now, the company is heading to IPO, 44filing for a ₹1,900 crore public issue.

But beyond the big number, what’s actually happening inside Urban Company? How strong is the business? And are there risks that investors may not spot at first glance?

We went through the 568 pages of their IPO papers, and let us tell you all the interesting things we came across.

The basics

Let’s start with the basics.

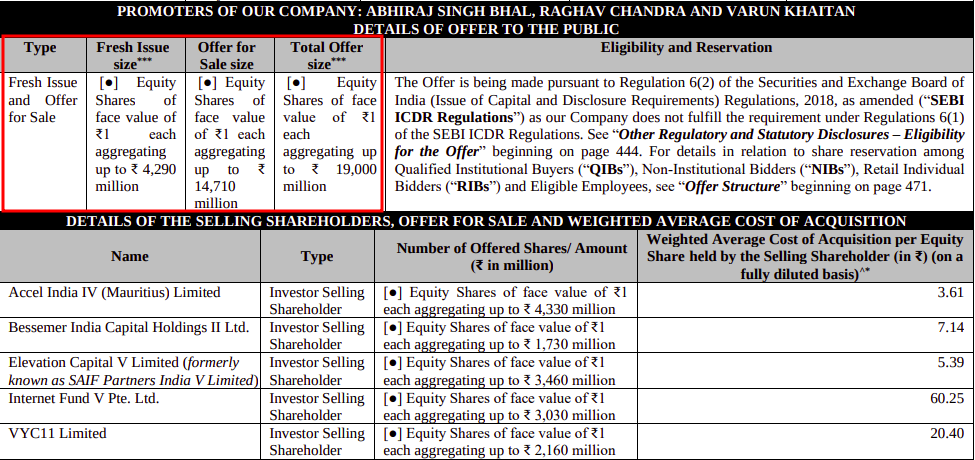

The size of the issue is ₹1900 crore. Incidentally, ₹429 crore of that will actually go to the company. The rest, ₹1,471 crore, is an “Offer for Sale”. That is, the venture capital funds behind the company — Accel, Bessemer, Elevation Capital and others — will now cash out.

Out of the ₹429 crore that Urban Company gets, most of it goes to product and platform upgrades — with ₹190 crore earmarked for new tech and cloud infra. ₹80 crore will go towards marketing, and ₹70 crore for leasing new office/training spaces.

Some of that fresh issue might get shaved off further via a ₹85 crore pre-IPO placement. In simple terms, this means the company might raise part of its primary capital in a private round before the IPO opens. If it does, that amount will be deducted from the final IPO offer.

Urban Company breaks even

Between March and December 2024, Urban Company reported about ₹846 crore in operating revenue. That was a huge 40% jump over the ~₹600 crore it took in over the same nine months last year. FY 2024, too, had been a solid year, with an operating revenue of ₹828 crore — a 30% leap from one year before.

What really caught our attention, though, was the company’s bottom line. After years of burning hundreds of crores, between March and December 2024, they reported a net profit of ₹242 crore — the first in their history. It looks like the company, after years of burning through VC money, is turning into a money-making entity.

Except — that’s not the full story.

That profit figure includes a one-time deferred tax credit of ₹215 crore. Strip that out, and those profits shrink considerably — to a mere ₹27 crore. That still means the business has reached its break-even point. That is a big deal for a company that was in losses for its entire lifetime so far.

That said, if you just go by its latest results, you might overestimate its earning potential.

How did it manage the turnaround?

The company successfully cut its costs over the last year. Its overall expenses have only grown 23% compared to a ~41% growth in revenues for the 9 months ended 31st December, 2024. That’s a great sign.

But are these cuts something you can bank on?

There are some places where we, at least, are unconvinced. Take its employee benefits expenses, for instance, which stayed almost flat-ish. Dig deeper, though, and the notes to accounts show that even while the salaries or wages paid to the employees have actually gone down by 4%, the share based component has gone up by 40%.

That isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It could mean the company’s learning to conserve cash, while incentivising its employees to take long-term ownership in the company. But it does point to the possibility that this share-based expense component may grow in the future, compensating employees for services they’ve already delivered. We can’t say for sure, just yet. There are other jurisdictions where this sort of thing has come under scrutiny.

This isn’t quite a red flag. But it’s worth paying attention to.

Understanding Urban Company’s business

Urban Company is India's largest home services marketplace. It frankly transformed the fragmented sector for these services through its technology-driven solutions — inventing a whole new segment for itself.

The fulcrum around which Urban Company rotates is its workers. If you want to understand the business and its prospects, that’s where we recommend you look.

Urban Company had about 48,000 monthly active service professionals during 2024. These aren’t employees, they’re “partners” — freelancers who use the platform to get work. Urban company is part of the wave of gig-based businesses that have taken India by storm over the last decade.

What does that mean? The company trains these gig workers, sells them tools and consumables, assigns them jobs via the app, and enforces quality standards. It gets a cut for doing all this. But that’s as far as it goes. It doesn’t give out a fixed salary, benefits, or job security. These gig workers bear a lot of the downside if Urban Company can’t generate enough business.

This can be a double-edged sword for Urban Company. It has all the advantages that gig companies generally have. But it also carries their latent risks.

Urban Company’s value proposition

At its heart, Urban Company offers its customers and workers a technology platform. This platform connects customers to professionals of various sorts — from electricians, to beauticians, to plumbers — within a 5 km radius. It also acts as a quality filter, ensuring that customers get services of a quality that’s above a certain baseline.

That’s a simple enough idea, but it unlocks a lot of efficiency for everyone involved.

For customers, Urban Company quickly becomes a one-stop shop for a large variety of services. This creates a substantial degree of stickiness. Going by the company’s offer document, once on-boarded, customers keep coming back to the platform, trying out an ever-increasing range of services from the platform.

For professionals, on the other hand, the platform becomes a convenient way to source customers. Professionals on the platform supposedly earn 30-40% more than those that aren’t on any platform. They also get a variety of incidental services: like invoicing and collecting payments.

Together, this becomes a flywheel. The platform has strong network effects, that is, it only gets better with scale. The more people use Urban Company, the more useful it becomes. As the company gains more customers, it becomes more useful for professionals. And the more professionals it has, the more customers want to use it.

What keeps gig workers on

This entire model depends on Urban Company being able to keep a steady supply of gig workers. There are definitely reasons that they’ll stick on: it’s a fantastic way of gaining customers, after all. But is it enough?

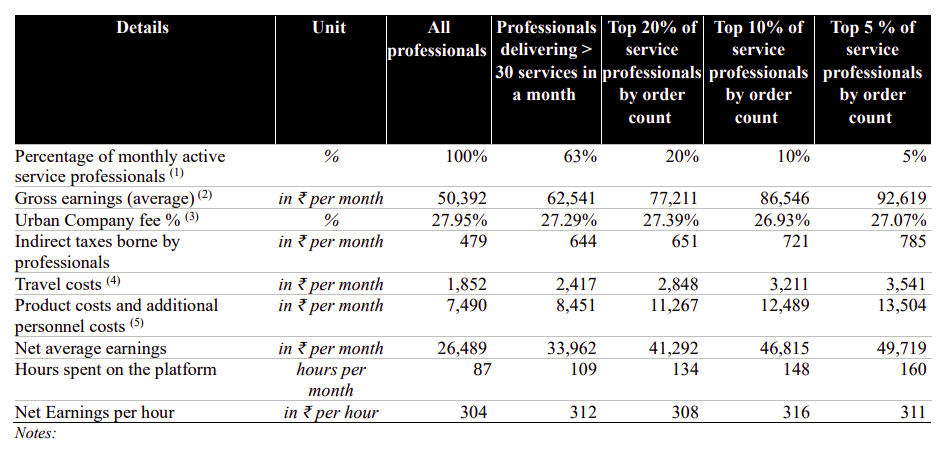

Urban Company says its partners retain about 72% of what customers pay. But this doesn’t account for their costs: for travel, barcoded consumables that they are pushed to buy, and the occasional add-on staff they must pay for in team-based services. Basically, they internalise most major costs (other than those for customer acquisition) for providing their services, while taking a 30% haircut on their topline.

In all, on average, they earn ₹304 an hour after deducting platform fees, travel, product costs, and taxes. The earnings potential doesn’t scale according to the time they give the platform. Even for the top 5% of workers by number of tasks, their hourly earnings — at ₹311 — barely move.

Basically, as a service provider, there’s a cap on what you can make from the platform. Your average returns remain the same, whether you’re an occasional user of the platform, or a power user.

This might mean there’s very little stickiness for partners on the platform. For instance, this can increase off-platform services: once a customer meets a reliable service partner, they might just call them directly next time, instead of going via Urban Company. This way, the customer saves the platform fee, while the partner keeps more money. This problem is especially critical in categories like beauty and cleaning, where customer loyalty is high, and frequency of orders is strong. Every repeat job done outside the platform is a hit to both revenue and retention.

While Urban Company dominates its space, it can survive small leakages. But hypothetically, if there’s a competing platform that emerges tomorrow, it could quickly make a serious dent in this core resource the company has — even by simply offering comparable rates.

This isn’t just a theoretical concern. Swiggy has just ventured into the professional services market with the launch of 'Pyng'. Its AI-powered app connects users with verified professionals across various fields, including health, wellness, finance, and events.

Pyng has a long way to go before it matches Urban Company’s scale. It is currently operational in select cities like Bengaluru. But its entry signifies potential competition for Urban Company in the near future, crowding up what was otherwise a complete white space for the company.

To keep its partners on, the company offers some perks — like the ability to move up “tiers” (Bronze, Silver, Gold). With that comes access to loans, training, and a predictable stream of demand. But it’s not a long-term career for most people. It’s a model that only works as long as there’s heavy demand for small gigs. Attrition could become a real challenge for the company some day, though the company doesn’t publish exact percentages.

Signs of discontent

Even without competition, there have been some signs that Urban Company’s partners aren’t entirely happy with how they’re treated. Every once in a while, there are news reports of fresh strikes by its partners.

Two years ago, for instance, Wired published a deep-dive on Urban Company’s partner ecosystem — especially its impact on women workers.

The piece told the story of Nazia, a data-entry worker in Hyderabad who spent nearly ₹40,000 to join the platform as a beautician. For a while, it worked. She bought a two-wheeler, helped out her family, and even saved for her wedding. But then came a sea of metrics — minimum acceptance rates, rating thresholds, monthly cancellation limits. One misstep led to her being blocked from the platform. She was pushed into "retraining," and had to complete 10 free bookings to be reinstated, but her rating didn’t improve. She’s now stuck with ₹2 lakh in debt.

The article documents multiple women being deactivated for missing metrics by a sliver — 4.69 instead of 4.7. As one of the women quoted by Wired said: “They call us partners, but don’t treat us like it.”

Some of this comes with the territory. From Swiggy to Uber, most companies that employ gig workers periodically deal with worker unrest. But as the company itself admits, this discontent is a continuous latent risk for its business.

The costs of managing such a big workforce

There’s one thing that sets Urban Company apart from other gig platforms. Its gig workers perform more complex tasks than those on platforms like Swiggy or Uber. And that means the company has to spend a lot more on them.

Urban Company spends heavily on training gig workers — with over 220 classrooms across 15 cities, mentoring programs, and onboarding kits that include tools and uniforms. In fact, onboarding and training alone cost them ₹137.3 crore in 2024 — 24.4% of the India services revenue. Even in just the nine months to December, it was ₹115.7 crore — or 22.1% of revenue.

Skill-building isn’t the only cost it takes up. Urban Company tightly controls the entire service stack: it sells tools, sets standards, monitors every job via customer feedback, and even verifies product use through barcoding. That level of standardization isn’t cheap.

To an extent, this is a moat for the company — and the company lists it among its competitive strengths. Its heavy investments in training and quality control are what helps it maintain standards, which is fundamental to its business offering. But it’s also a source for risk: if a professional leaves, all that investment is lost.

This makes Urban Company a unique entity within the gig economy. Their workers aren’t as replaceable as those of other gig platforms. Attrition hurts Urban Company much more than other gig-based companies.

What about their international business?

Urban Company isn’t just an India-focused company. It’s also live in Singapore, UAE, and Saudi Arabia. But establishing itself in those markets isn’t easy. Despite five years of effort, it hasn’t cracked those markets financially.

In the nine months ended December 2024, the international segment earned around ₹116 crore in revenue — about 14% of total operations. But it’s yet to break even. In the same period, it posted a negative Adjusted EBIDTA loss of around ₹37 crore.

This doesn’t just reflect a short-term cash burn. The company’s cumulative EBITDA losses from its international markets over the last three years are staggering. Saudi alone contributed ₹23.5 crore in losses in 2024. The company has now moved to a joint venture structure there — which is code for: “Let’s limit the bleeding and offload some risk.”

Urban Company argues that these markets — especially UAE — are attractive due to the Indian diaspora and high disposable income. But the reality is that labor laws, competition, and cost of customer acquisition are all tougher abroad. And the repeatability of services — which Urban Company thrives on in India — is not guaranteed in those markets.

From what we can tell, the company’s international expansion is being talked down in the IPO. And if that’s the case, we can see why.

So, here’s where we stand

This IPO, isn’t a story of a company that’s cracked the code. It’s the story of one that’s finally stabilised after a decade of experiments — but now faces its biggest test yet: sustaining quality, loyalty, and growth, all at the same time, under public market scrutiny.

Bajaj Finance Q4 FY25: Great Results, But Sky-High Expectations

Bajaj Finance has just announced its Q4 FY2025 earnings, delivering what most companies would consider stellar results. Assets under management (AUM) grew about 26% year-on-year in Q4. Consolidated net profit came in around ₹4,546 crore (up ~19% YoY), and its Net NPA held steady at a low 0.44% – among the best asset quality metrics in the industry.

And yet, the stock fell ~5% after the results.

This would probably leave you puzzled if you just saw the headline figures. From our limited understanding, Bajaj Finance was just a victim of sky-high expectations. The market was pricing in an A+ report card, and when Bajaj merely delivered an A — it was punished.

Investors probably also honed in on the management’s less optimistic outlook for the future — as it slightly downgraded its growth outlook and acknowledged higher credit costs ahead. For FY26, Bajaj trimmed its AUM growth guidance slightly to 24–25% (from 25–27% earlier). It also nudged up its credit cost guidance to 1.85–1.95% (from 1.75–1.85%). Its expected ROE was dialled back to ~19–20% (vs 21–23% prior).

But that’s just the headlines. We want to share a couple of interesting things we found out while going through these results, just as we did last quarter.

Let’s dive in!

First, the ECL model got refresh

A key factor that weighed on Bajaj’s Q4 performance was the annual refresh of Bajaj’s Expected Credit Loss (ECL) model — which threw a sudden curveball.

See, this “expected credit loss” model gives the company an estimate about how much of the loans they’ve given out won’t be paid back. Each year, Bajaj recalibrates its provisioning model based on recent trends. This time around, they incorporated a rise in early delinquencies and a more cautious macro outlook. The result was an extra ₹359 crore provision in Q4.

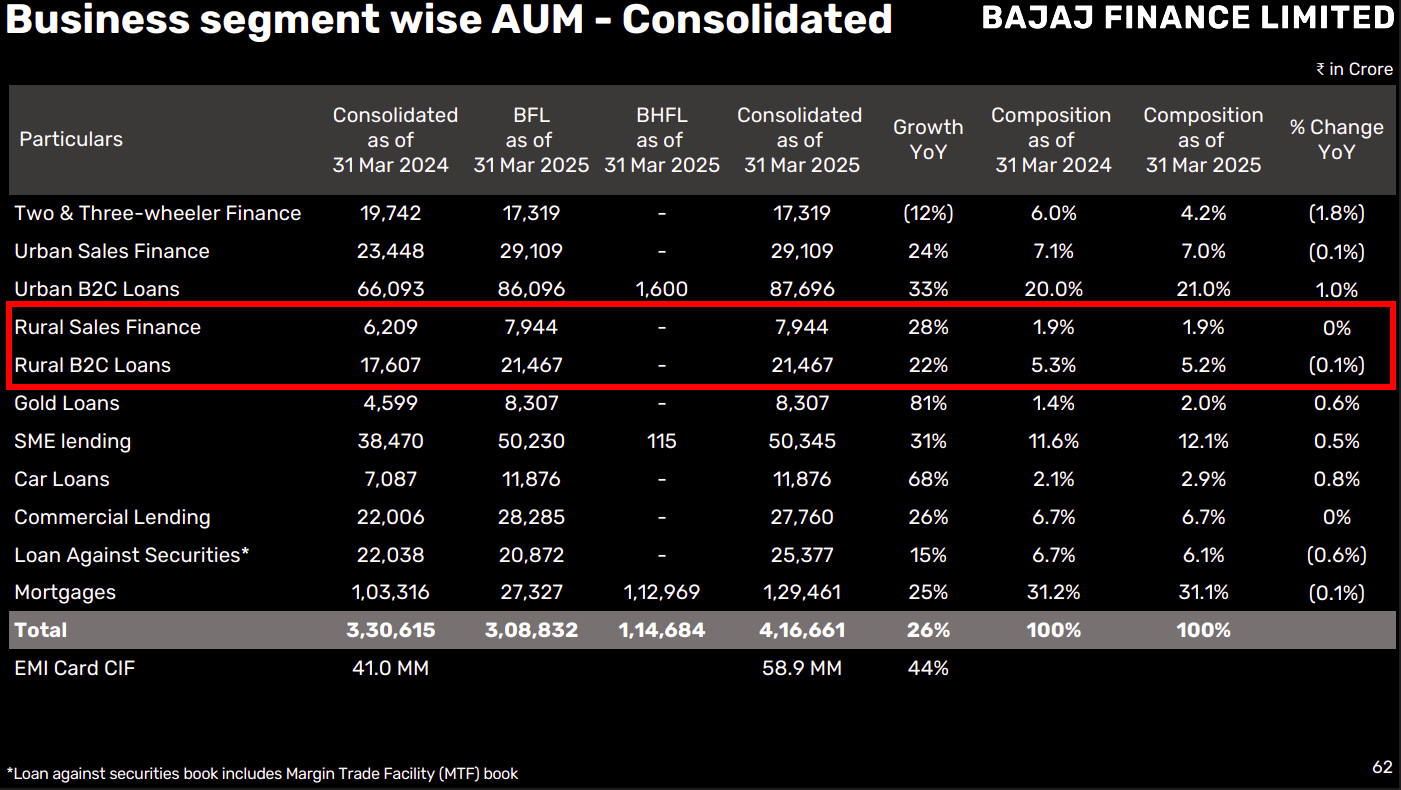

Essentially, Bajaj pre-emptively set aside a much larger buffer of cash for future credit losses — given all the warning signs it’s seeing. The root cause of this uptick was the stress in its rural and unsecured retail segments. The way we see it, though, this adjustment is a conservative step: the company is acknowledging risk before it erupts.

The company’s tone in its earnings call underscored that credit quality is paramount to it. As Anup Saha, its new MD, emphasized, Bajaj Finance would rather moderate growth than tolerate undue credit risk.

When a company puts money aside as provisions, that counts as an expense in its books — which makes its lending look more costly. The sudden hit drove the company’s Q4 credit cost up to 2.33% of average assets, compared to 2.1% in the previous quarter. But that doesn’t account for everything. Even excluding this change, the full-year FY25 credit cost for the company ended above its previous guidance at ~2.0%, missing the 1.75–1.85% range the company had hoped to stick to.

Not surprisingly, management expressed disappointment about this miss on the credit front. Saha candidly noted:

“Credit cost we said 175 to 185 bps – this is where we are not happy about it… we are in a business of credit, so if we miss on credit, we don’t like it.”

Now, this isn’t permanent. The management expects credit costs to gradually trend down hereafter. But it did dent the company’s FY25 bottom line, and hurt confidence.

Second, rural lending may have bottomed

But things are not all doom-and-gloom. The troubled pockets the company pointed to – especially rural lending – are showing early signs of stabilization.

In fact, its rural B2C (business-to-consumer) loans grew 9% QoQ in Q4. That’s a solid rebound after a couple of soft quarters. Bajaj had deliberately slowed growth in the rural segment earlier in the year due to higher defaults, but demand seems to be recovering.

People are paying these loans off more readily too. As the company noted, its 6-month-on-book delinquency metrics are now better than they were back in late FY24. That is, the loans that began more recently in rural areas are performing well.

Even in more turbulent times, the company’s rural B2B (business-to-business) portfolio held up strongly. So, as things recover, Bajaj is confident about its franchise in smaller towns.

All this leads Bajaj’s team to believe the worst is over in rural India. As Vice Chairman Rajeev Jain said in its earnings call:

“Rural B2C is improving… we remain very confident from here to grow the rural B2C business”

Hopefully, the company’s rural book will resume healthy growth. Jain highlighted that the in qcompany improved its debt management and collections in rural areas, which is yielding results.

On top of that, the growing network of small businesses in rural areas that the company has lent to, gives it the opportunity to cross sell other products to them. The company is also looking to pace up the growth of retail lending in rural areas towards the 20-25% range going forward.

Third, the margins are under pressure, but rate cuts could help

Another area where the company “failed to match expectations,” as some analysts put it, was its ‘net interest margin’ (NIM). Bajaj’s NIM fell by about 49 basis points in FY25, which was steeper than the ~30–40 bps dip management had initially expected. Essentially, while the company had to spend more to arrange for funding, it couldn’t pass nearly as much of that cost to its borrowers.

The reason isn’t hard to find: the RBI held interest rates high throughout the year, holding off on rate cuts until late this January. As a result, Bajaj’s cost of funds in Q4 climbed to 7.99%, slightly up from Q3.

From what we can tell, its margins will improve in FY26. Bajaj expects its funding cost to fall by 10–15 bps in FY26. In fact, the management expects three repo rate cuts (~75 bps total) over the next year, which should make borrowing much cheaper for it.

About 75% of Bajaj’s borrowings are on fixed rates, so the costs on those borrowings would not go down drastically. But, new borrowing rates have already started to soften. The company raised a healthy amount of deposits as well — its deposit book was up ~19% from last year — which diversified its funding. All told, Bajaj is guiding for stable NIM in FY26 – the slight dip in cost of funds should offset any pressure on the rates that it gives out loans.

Fourth, non-interest income also faces headwinds

Bajaj Finance doesn’t just care about its interest income – fees and other charges are an important part of its revenue. In Q4, however, these other streams of income fell by ~8% from last quarter, which also crimped operating profit growth.

One big reason was a strategic shift: Bajaj stopped sourcing new co-branded credit cards (with RBL Bank and DBS Bank) in late 2024. Until then, it used to help originate and service cards issued by partner banks — which created a steady stream of money as fees. In response to regulatory directions from RBI, though, Bajaj Finance had to exit the co-branded credit card business. This meant the company forewent the fees and commissions it used to earn from adding new credit card customers.

Moreover, Bajaj has generally been moderating certain fees and charges – for example, it reduced penal interest rates and certain origination fees – in order to align with regulatory expectations and enhance customer experience. These moves may be smarter for the company in the long run, but they put a near-term drag on fee income growth.

Despite these headwinds, though, Bajaj’s fee and other income isn’t expected to stagnate – they’ll just grow at a more modest pace. Management has guided for 13–15% growth in fee and other income in FY26. That’s healthy but lower than what it could bring in when its co-branded card business was active.

Finally, a few more nuggets from the quarter

Beyond the headline numbers, the Q4 report and commentary had a few notable nuggets that shed light on Bajaj Finance’s strategic priorities:

De-risking the Unsecured Book: Bajaj has deliberately curtailed lending to customers who are over-leveraged or simply borrowed more than their ability to pay back. In fact, it brought the share of its customers that have taken 3 or more unsecured loans at the same time — its riskiest customers — down to about 9–10% of its retail customers, from ~13% at its peak. It’s now back to pre-Covid levels (~8%).

By pruning exposure to borrowers who had stacked multiple personal loans/consumer loans, Bajaj likely sacrificed some short-term loan growth. However, this move has de-risked the book significantly, preventing an even larger blow-up in credit costs.

Investing in People and Control: In Q4, Bajaj Finance transitioned ~44,650 personnel from outsourced roles to fixed-term employment under the company. Most of them were front-line staff in sales and collections agents — people who were previously on third-party payrolls. With this move, total employee headcount swelled to ~64,000 as of March 2025.

Now that these people are directly employed by the company, it has a better hold on their training, and service quality. Critical functions, like collections in far-flung locations, should improve when workers feel part of the company and are better supervised.

Conclusion

Overall, Bajaj Finance’s Q4 FY25 story is one of a high-performing franchise making tactical adjustments in a more challenging environment. The company is still delivering robust growth and profitability – few lenders of its size are growing AUM 25%+ with sub-1% gross NPA.

But Bajaj is no longer in a zero-credit-cost, easy liquidity world, and it’s adapting accordingly. Its management is thinking long-term. It’s choosing to prioritize credit quality and operational resilience over breakneck growth. That may not be to everyone’s liking, but it’s not necessarily a bad thing.

The market’s expectations game can overshadow fundamentals in the short run. But if the company delivers on its recalibrated guidance, that lost confidence should return. Bajaj Finance remains a benchmark for what a well-run NBFC can achieve – even its “A instead of A+” results are far ahead of most peers.

Tidbits

IndusInd CEO Resigns Amid ₹1,960 Crore Derivatives Accounting Lapse

Source: Business Standard

Sumant Kathpalia, MD & CEO of IndusInd Bank, resigned citing moral responsibility after an investigation revealed accounting discrepancies in the bank’s internal derivatives portfolio amounting to ₹1,959.98 crore as of March 31, 2025. The lapses involved incorrect treatment of early-terminated internal derivative trades, which led to notional profits being recorded. Earlier, PwC had validated a similar adverse impact of ₹1,979 crore as on June 30, 2024. The resignation comes weeks after the RBI extended Kathpalia’s term by only one year despite the board recommending three. Deputy CEO Arun Khurana also resigned earlier in connection with the same issue. IndusInd’s market cap declined to ₹65,230 crore by April 29, from ₹74,808 crore reported in 9MFY25.

BPCL Q4 Profit Rises 8.3% YoY to ₹4,392 Cr, GRMs Improve to $9.2/Barrel

Source: Business Line

State-run Bharat Petroleum Corporation Ltd (BPCL) reported a consolidated net profit of ₹4,392 crore in Q4 FY25, marking an 8.3% year-on-year increase and a 15.4% rise sequentially. The growth was driven by improved gross refining margins (GRMs), which stood at $9.20 per barrel in Q4 compared to $5.60 in Q3. However, the average GRM for the full year declined sharply to $6.82 per barrel from $14.14 in FY24. Total income during the March quarter was ₹1.28 lakh crore, flat on a quarter-on-quarter basis and slightly lower than ₹1.33 lakh crore in the same quarter last year. Expenses were ₹1.22 lakh crore, marginally down from both Q3 and Q4 of the previous year. BPCL ended the fiscal with a cumulative under-recovery of ₹10,446.38 crore. Operationally, the company achieved its highest-ever annual throughput at 40.51 million tonnes and record market sales of 52.40 million tonnes, with Q4 throughput and sales growing to 10.58 mt and 13.42 mt, respectively.

Mother Dairy Hikes Milk Prices by ₹2/Litre Citing Rising Procurement Costs

Source: Business Line

Mother Dairy has announced an increase of up to ₹2 per litre in milk prices across Delhi-NCR, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, and Uttarakhand, effective April 30, 2025. The company cited a ₹4–₹5 per litre rise in procurement costs over recent months, attributing it to the early onset of summer and prevailing heatwave conditions. As a result, the price of a 500 ml pack of full cream milk will rise from ₹34 to ₹35, while toned milk will move from ₹28 to ₹29. The revision, according to Mother Dairy, represents only a partial pass-through of the increased input costs. The company stated that the move aims to balance farmer livelihoods with consumer affordability. This is the latest instance of input cost pressures affecting essential food categories. While Mother Dairy is not listed, the development may be closely watched by stakeholders across the dairy value chain.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Krishna.

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉