Understanding Shipbuilding Industry from scratch

ft. Ishmohit Arora

Hi folks, I am Kashish Kapoor and I went into this conversation with Ishmohit (SOIC Finance) thinking shipbuilding was one of those “important but uninvestable” sectors. Too slow, too bureaucratic, too government-heavy, too far from anything that resembles consumer demand.

And then he opened with a line that reframed the whole sector:

“he who controls the sea controls the world”

That’s the thing with shipbuilding. You can’t keep it “just industrial”. The moment you zoom out, it becomes strategy. Strategy becomes policy. Policy becomes capital allocation. And suddenly, this “boring” sector starts looking like a national capability.

This post is my synthesis of what I learned in that chat with him. I’ve kept it simple, practical and focused. If you like the write-up, you can always watch the full podcast here.

You can also listen to this on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

Geopolitics, trade, and the forex leak nobody talks about

Here’s a fact that’s both obvious and underappreciated: India’s trade lives on the sea. The government itself notes that nearly 95% of India’s trade by volume and around 70% by value moves through maritime routes.

Now ask the uncomfortable follow-up: if seas carry our trade, whose ships carry it?

A useful anchor number: in FY20, India paid about $85 billion in sea freight, and roughly $75 billion went to foreign shipping companies. That’s not just “cost” but recurring foreign-exchange outflow. And in a world where geopolitics can shut routes, jack up insurance, or make vessels scarce, shipping capacity becomes leverage.

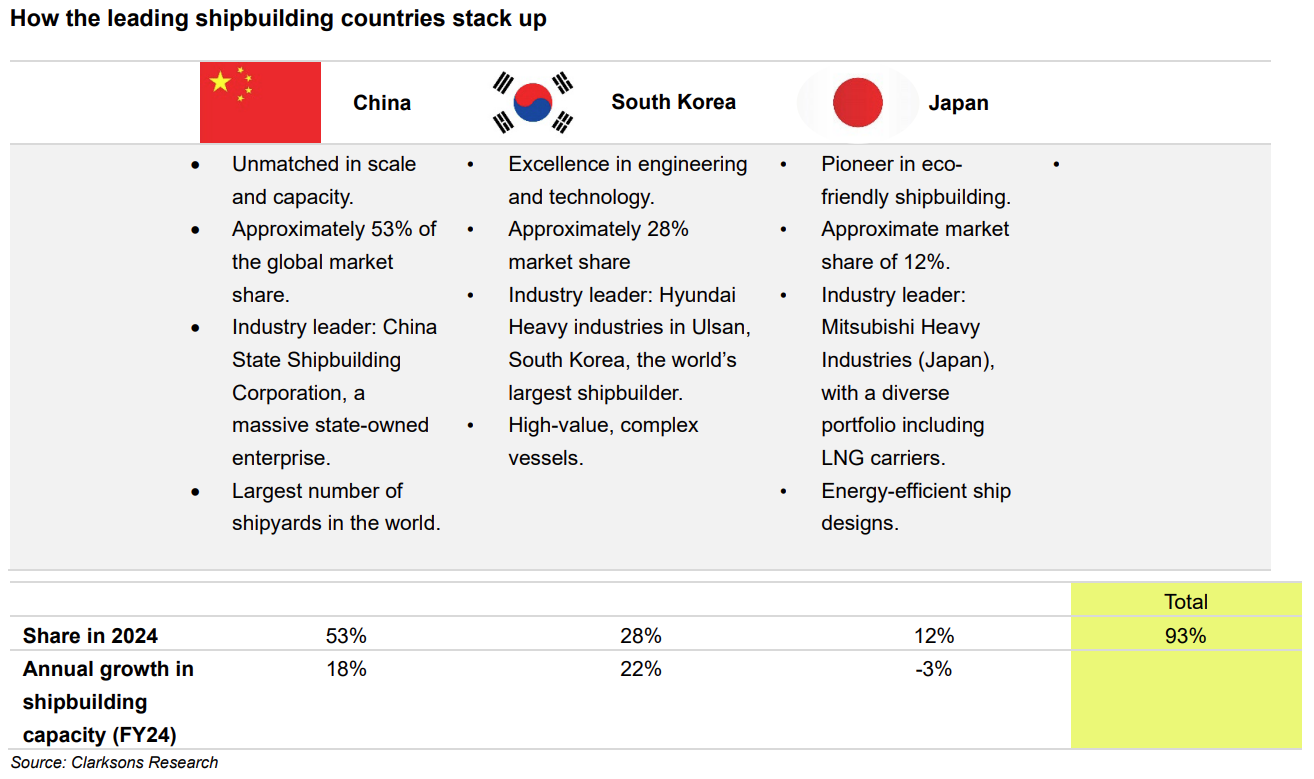

Then comes the neighbourhood reality. China’s navy is assessed by U.S. DoD as the largest in the world by number of battle force ships, with “over 370” platforms and projected growth ahead. Meanwhile, global commercial shipbuilding is heavily concentrated: in 2024, China, South Korea, and Japan produced about 95% of global shipbuilding output, and China delivered over half of the world’s capacity for the first time.

When a country can build ships at scale and deploy them at scale, shipbuilding stops being a sector and starts being leverage.

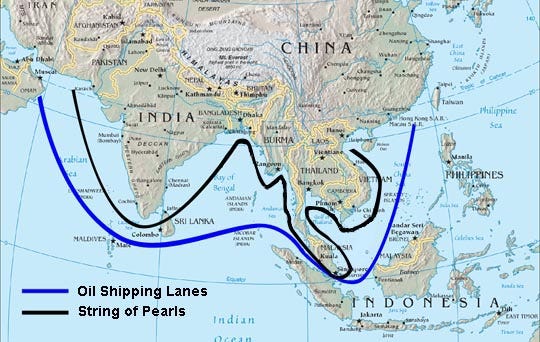

This is also where you hear phrases like the “String of Pearls” — the idea that China’s commercial port investments across the Indian Ocean can double as strategic footholds (think: military).

The concept itself is debated: some analysts treat it as a useful lens, others call it over-interpreted.The practical takeaway for India doesn’t depend on whether you love the phrase or hate it: sea lanes and ports are geopolitical assets now, not just trade infrastructure.

Even geography becomes part of this story. India’s Ministry of Ports/Shipping describes the planned International Container Transshipment Port (ICTP) at Galathea Bay (Great Nicobar) as strategically positioned near the Malacca Strait—one of the world’s key maritime corridors linking the Indian and Pacific Oceans. (And yes, estimates vary, but the Strait of Malacca is widely described as one of the world’s busiest and most critical trading lanes.)

I’m not starry-eyed about any of this. But if you want the clean investment takeaway: shipbuilding is where trade + defence + geography collide. Ignore one corner of that triangle and you’ll misunderstand the whole thing.

Shipbuilding isn’t one business

Most people say “shipbuilding” and imagine one thing: a shipyard.

Yes, the shipyard matters. And Ishmohit’s definition is the simplest one I’ve heard:

“shipyard is nothing but a huge factory for making ships”

That factory typically does four jobs: build, repair, maintain, and modify. And that matters because a yard’s revenue can be a mix of glamorous new-build projects and steady repair/maintenance work.

But the ecosystem is bigger than the yard.

There’s the asset-owner / charter model: you own vessels and rent them out. The catch is that “rent” (charter rates) can swing wildly with global supply-demand and commodity cycles. Ishmohit said it plainly:

“commercial shipping ki side pe charter rates track karne padenge”

In normal language: you can’t model this like a stable consumer business.

There’s the niche-builder model: instead of trying to build everything, you build capability in specific vessel categories and become hard to replace.

And there’s the unsexy plumbing: dredging, port-enabling services, and the jobs that make the water literally navigable for bigger ships. If India is serious about port expansion, dredging is an unavoidable bottleneck.

The key point: before you even think about “the shipbuilding theme”, decide which business you are actually talking about. Factory, fleet-owner, niche builder, or maritime infrastructure services—they behave differently.

Commercial vs military: two worlds, two contract logics

I used to lump commercial and defence shipbuilding together. That was lazy.

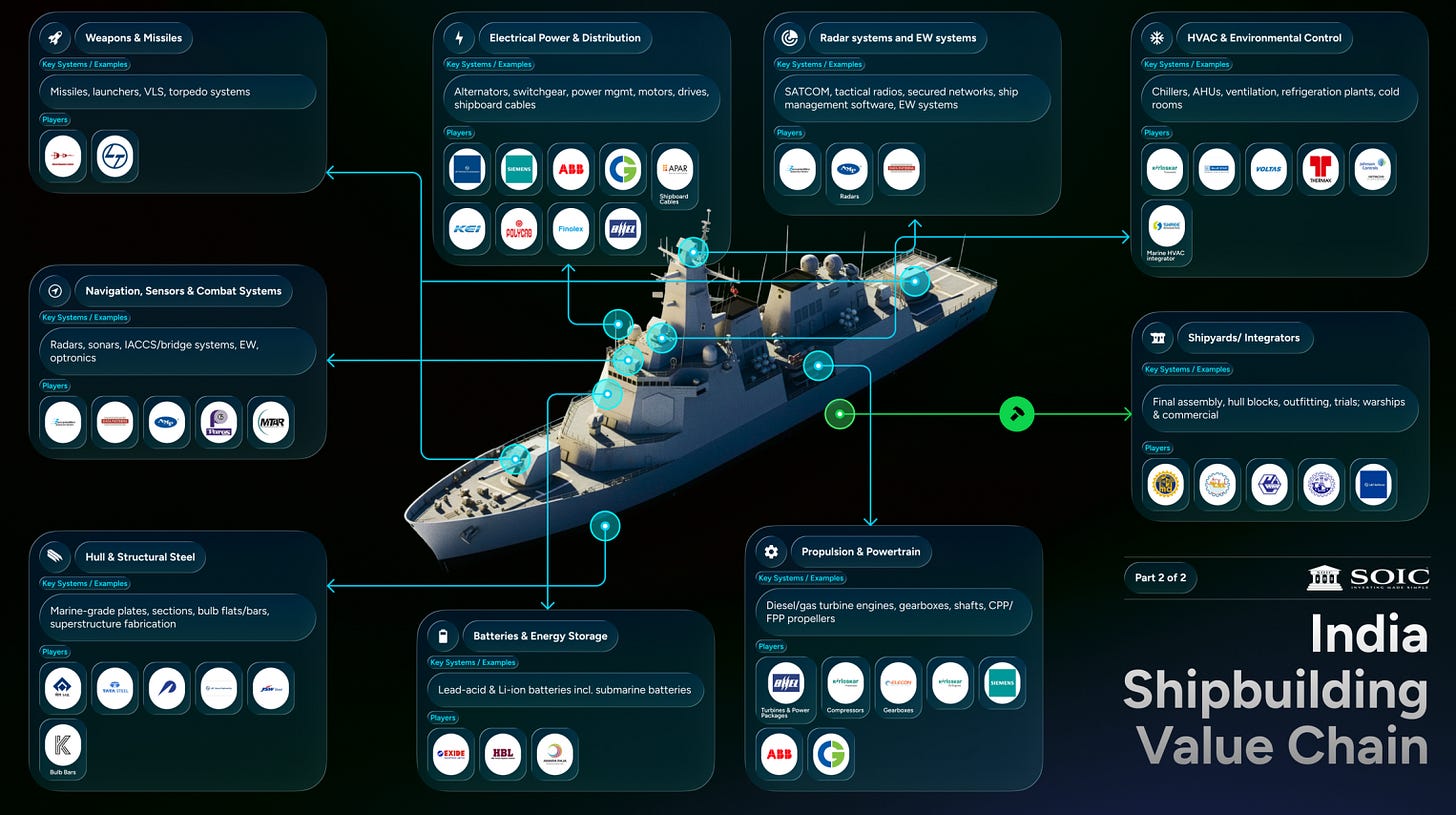

Commercial shipbuilding behaves like global manufacturing: cost, delivery time, financing, and cycles. Defence shipbuilding behaves like state capability: the buyer is the government, timelines are longer, and the “ship” is really a floating integration of complex systems.

That’s also why governments intervene here. Ishmohit summed up the dependency in one line:

“requires a very strong government and a political will”

India’s policy push is increasingly explicit: infrastructure status for large ships (to unlock better financing), a Maritime Development Fund, and shipbuilding development schemes aimed at clusters and capacity building.

And this “dual-use” idea matters. Defence-led innovation often spills into civilian markets. DARPA’s own history page describes how early ARPA/DARPA work on ARPANET fed into the conceptual basis for today’s internet. The lesson isn’t “shipbuilding will create the next internet.” The lesson is: some industries are treated as national capability first, commercial opportunity second.

Indigenization: what can be localized quickly, and what’s actually hard

We throw “Make in India” around like it’s a switch. It’s not. It’s a staircase.

This is the line from the podcast that captures the real transition:

“from import and operate; to becoming a system integrator”

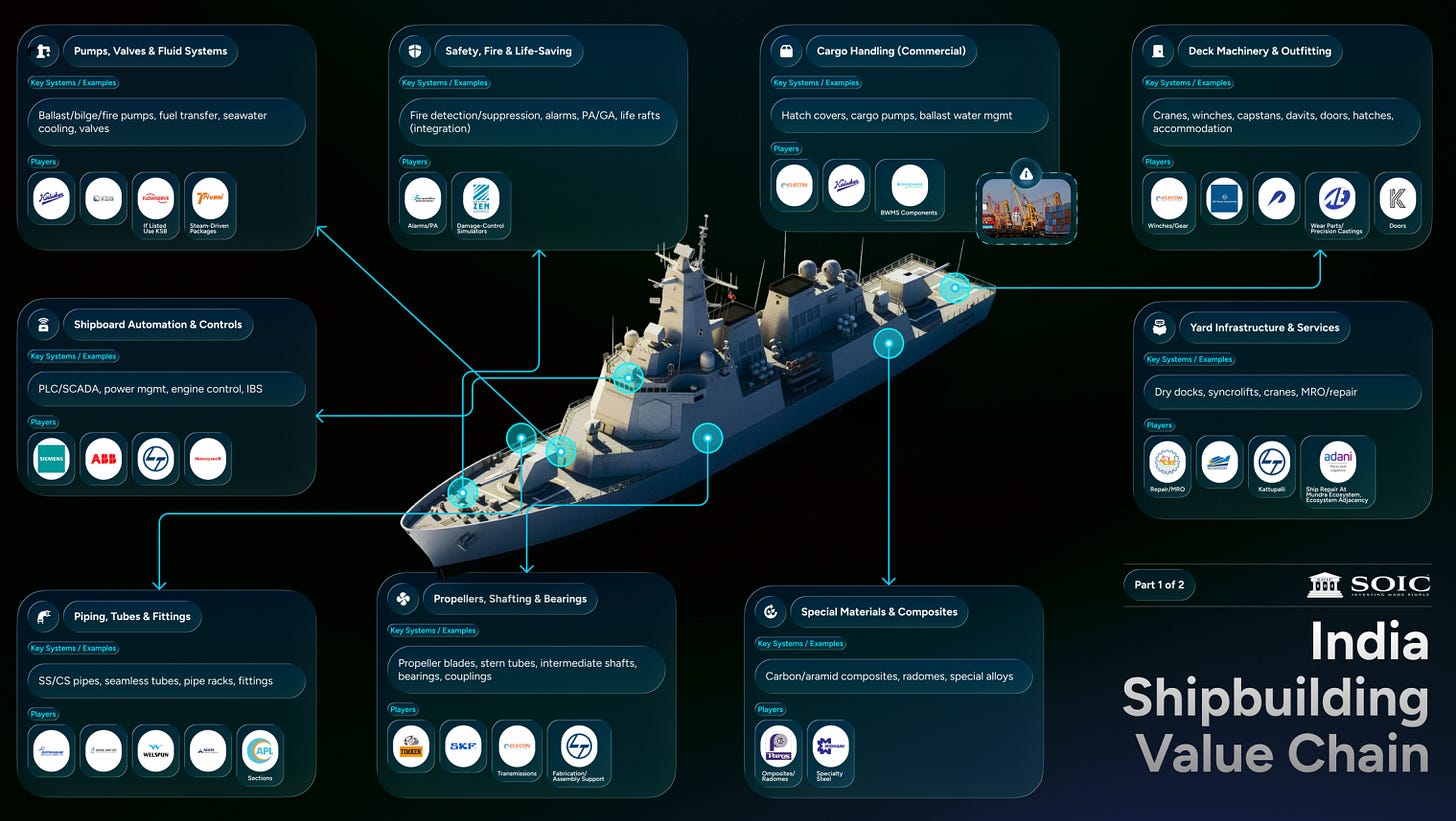

Becoming a “system integrator” means: even if you still import some high-end subsystems, you control the architecture, the assembly, the testing, the upgrades—and you gradually localize components as your ecosystem learns.

A practical way to think about indigenization in shipbuilding:

Some parts are heavy and difficult, but doable with skills + scale (fabrication, outfitting, many mechanical/electrical subsystems). Some parts are deep-tech hard (advanced propulsion and top-end sensors/electronics). Those take longer: R&D depth, export controls, and a supply chain that takes years to mature.

Why does this matter? Because indigenization isn’t just nationalist pride but also resilience. In a stressed world, “we can import it later” is not a plan.

How to shipbuilding financials without getting hypnotized

Now, I won’t dump company order-book numbers here. Now, that’s not to say that order-book numbers are not important, rather they are one of the most important figures to look at. But, numbers without context become a meme.

So here’s the framework I took away from Ishmohit’s explanation.

First, the warning line:

“you don’t want to be paying peak multiples at peak margin”

In long-cycle projects, profitability can look unusually high near the end of a contract. And revenue recognition for long-duration contracts often tracks progress over time, not only final delivery—meaning reported revenue/margins can shift depending on which stage of execution a company is in.

My simple checklist now looks like this:

[1] Execution cycle: How long does it take to build what they build? Shipbuilding is structurally long-cycle.

[2] Work mix: New-build vs repair vs upgrades. These aren’t the same cash-flow machine. It’s important to know, what part of the value chain is the company working towards.

[3] Margin quality: Are margins at a sustainable level, or are they peaking because certain high-margin milestones got recognized? Company conference calls are usually a great place to look for that.

[4] Cash conversion: Do profits turn into cash, or is cash stuck in working capital and milestone receivables?

If you only do one thing: normalize margins mentally and refuse to get excited about a single good year, while being on top of the order book pipeline for years to come.

Proxy plays

We ended the episode on “proxy plays”—and I like the concept, with one big caveat.

A proxy is when you don’t buy the shipyard; you buy the suppliers who benefit when shipbuilding activity rises: specialized metals, marine systems, gear systems, onboard power, sensors, HVAC, cranes, and so on.

This can be smart because suppliers can scale across multiple yards and even multiple industries.

But here’s the rule that saves you from self-deception: don’t buy a proxy unless shipbuilding is a meaningful chunk of its business. If it’s a tiny sliver, you’re basically buying a different company with a fashionable narrative attached.

My takeaway

Shipbuilding has a weird reputation: either it’s “boring government stuff” or it’s “the next multibagger theme”.

Both takes are lazy.

What I came away with is (hopefully) more grounded: shipbuilding is a bet on whether India can build a real maritime industrial base—yards, suppliers, skills, and financing—so we aren’t permanently outsourcing the pipes of our own trade. That’s a big if. Shipbuilding is brutally technical, and China didn’t stumble into dominance. It built it, patiently, over time. One comment on our video put it bluntly: “You will stop dreaming [building ships in India] if you visit even one shipyard in China.”

To be fair, we’re learning too, and we won’t pretend India isn’t far behind.

But the world isn’t getting calmer. Naval competition is rising, and shipping is getting greener (and more regulated). In that world, shipbuilding capability is less about pride and more about resilience.

If you want the full nuance—and the back-and-forth with Ishmohit—watch the podcast here.

Thank you for such a detailed article