Two indicators say the US is entering a recession

SEBI chair’s comments, How do you go from middle class to rich, Data that agrees with your beliefs, Now get bonus faster

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

Check out the audio here:

And, the video is here.

In today’s episode, we look at 4 big stories:

SEBI chair’s comments

How do you go from middle class to rich?

I just want data that agrees with my beliefs

You will now get bonus faster

SEBI chair’s comments

SEBI Chairperson, Mrs. Puri-Buch, recently spoke at a conference, shedding light on various stock market issues and SEBI's efforts to address them. One key topic she covered was SEBI's initiatives to improve the ease of doing business in India.

To tackle this, SEBI has set up 16 working groups, involving diverse market stakeholders like exchanges, clearing corporations, depositories, brokers, listed companies, AMCs, and alternative investment funds.

SEBI's larger goal is to help businesses by:

Reducing compliance burdens

Streamlining complicated processes

Improving investor protection

Facilitating faster access to capital

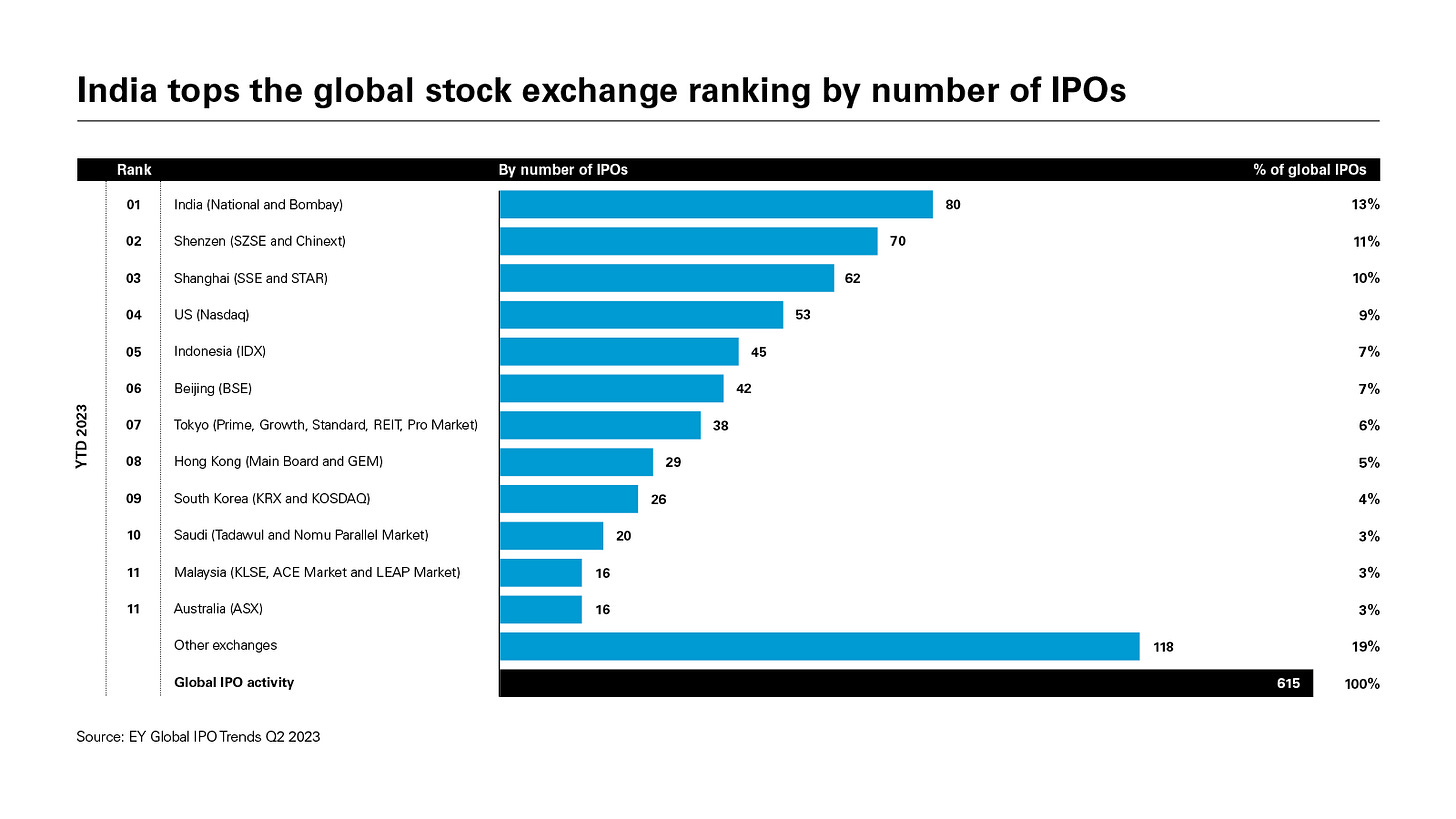

When it comes to faster access to capital, Mrs. Puri-Buch emphasized that while India leads globally in the number of IPOs and new issuances, our IPO processing time of 3-4 months is still relatively slow compared to global standards.

Source: EY

To address this, SEBI is focused on reducing IPO processing times by creating a "demystified IPO document." This document will be a template or fill-in-the-blank style format, covering all essential details of a company. The idea is to make the process less intimidating for companies and more informative for investors. The standardized format should also help reduce the processing time for IPOs.

Now, why is faster IPO processing important? A shorter timeline lowers the risk of market conditions changing between IPO filing and listing. Given the market's unpredictability, this is crucial.

More listings are essential because, as Mrs. Puri-Buch highlighted, there's currently a mismatch between the demand and supply of securities in the market. Over the last three years, about 3.1 lakh crore rupees have been invested annually in the secondary market by mutual funds, domestic institutional investors, and individual investors. However, only 2 lakh crore rupees worth of new stocks have been issued each year through IPOs and follow-on public offerings.

This means that the flows are chasing a limited number of securities, leading to an increase in existing stock prices without significant business growth to support it, which isn't healthy for market growth or the larger economy.

Ambit research echoed a similar sentiment, noting that the Availability Factor (AF) of Indian equities, which measures the ratio of available stocks to mutual fund demand, has been shrinking over the past seven years. The demand for Indian stocks from domestic mutual funds has grown faster than the supply of freely tradable shares. This effect is most pronounced in large-cap stocks, where the AF has decreased by 48%, compared to 33% for mid-caps and 27% for small-caps. In the last year alone, the large-cap AF dropped by about 9%. This trend has led to higher stock prices as more money chases a limited supply of shares, particularly in the large-cap segment of the Indian stock market.

How do you go from middle class to rich

The World Bank recently published a 276-page report on how developing economies can avoid the dreaded "middle-income trap." Instead of boring you with every detail, let me give you the gist of it.

So, what's the "middle-income trap"? Simply put, it’s when countries reach a certain income level and then get stuck, finding it hard to keep growing. Poor countries can grow quickly because they have lots of room to improve, starting with the easier problems. Rich countries keep growing because they’ve already solved many of their toughest economic issues. But middle-income countries have a tougher climb ahead.

Source: World Bank

Think of it like being stuck halfway up a mountain—you’ve come a long way, but there’s still a long way to go, and you’re already tired. Becoming a high-income country is a huge challenge and isn’t guaranteed. You need to get a lot of things right, and India is currently in this middle-income phase.

For countries like India, growth becomes tricky. We've made many obvious improvements, but we still have large, politically controversial problems to tackle. The simple solutions that worked when we were poorer don’t have the same impact anymore. To move forward, we need to compete with creative, technologically advanced businesses from around the world. This requires advanced technology, innovation, skills, money, and good policies.

Source: World Bank

The challenge is even harder because many opportunities that helped other countries in the past are now gone. Countries like China and Korea grew rapidly by exporting goods during a period of unprecedented globalization, when advanced economies encouraged them to become the world's factories. But that era has ended, and countries are becoming more protectionist. India doesn’t have the same opportunities as China and Korea did.

So, what's the solution? The World Bank recommends two key strategies for middle-income countries like India:

Infusion: Bring in and adapt technologies from advanced countries and spread them throughout the economy to improve technologically.

Innovation: Once countries reach technological parity with advanced economies, they need to innovate to gain an edge and push competitors out. This is tough and requires the right conditions to foster innovation.

Source: World Bank

Economist Joseph Schumpeter introduced the concept of ‘creative destruction,’ where an economy constantly experiences creation, preservation, and destruction. New businesses enter the market, successful ones grow, and failing ones are destroyed. Successful economies balance these three forces.

In middle-income countries, there are two main imbalances:

Fewer new businesses enter the market, slowing the creation of new ideas and technologies.

Incumbents are kept alive on life support, preventing bad companies from dying off. As a result, established businesses become complacent, relying on existing products without innovating.

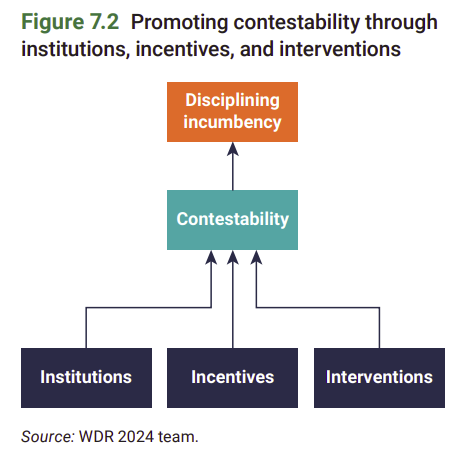

Source: World Bank

With fewer new businesses and less innovation, the economy gets stuck in the middle-income trap. So, how can countries get the balance right? Here’s what the World Bank suggests:

Discipline incumbents: Ensure big, established businesses don’t block new competitors or stifle innovation. This can be done by promoting fair competition and preventing monopolies.

Source: World Bank

Reward merit: Encourage and support talented people and good ideas, no matter where they come from. Give opportunities to those who show potential and have innovative ideas.

Make the best of crises: Use tough times, like economic or environmental crises, as opportunities to make important changes. These situations can help push through necessary reforms that might be difficult to implement otherwise.

Will India escape the middle-income trap? Only time will tell. But one thing's for sure—our generation will be the one to find out.

I just want data that agrees with my beliefs

We humans have all sorts of quirks, and one of the weirdest things we do is fall into the trap of confirmation bias. This means we look for or process information in a way that confirms our pre-existing beliefs.

Why am I bringing this up? Well, as I mentioned in yesterday’s episode, the global financial markets, including India, are looking quite bearish right now. We don’t really know why the markets are spooked, but one factor could be the increasing odds of a recession in the United States.

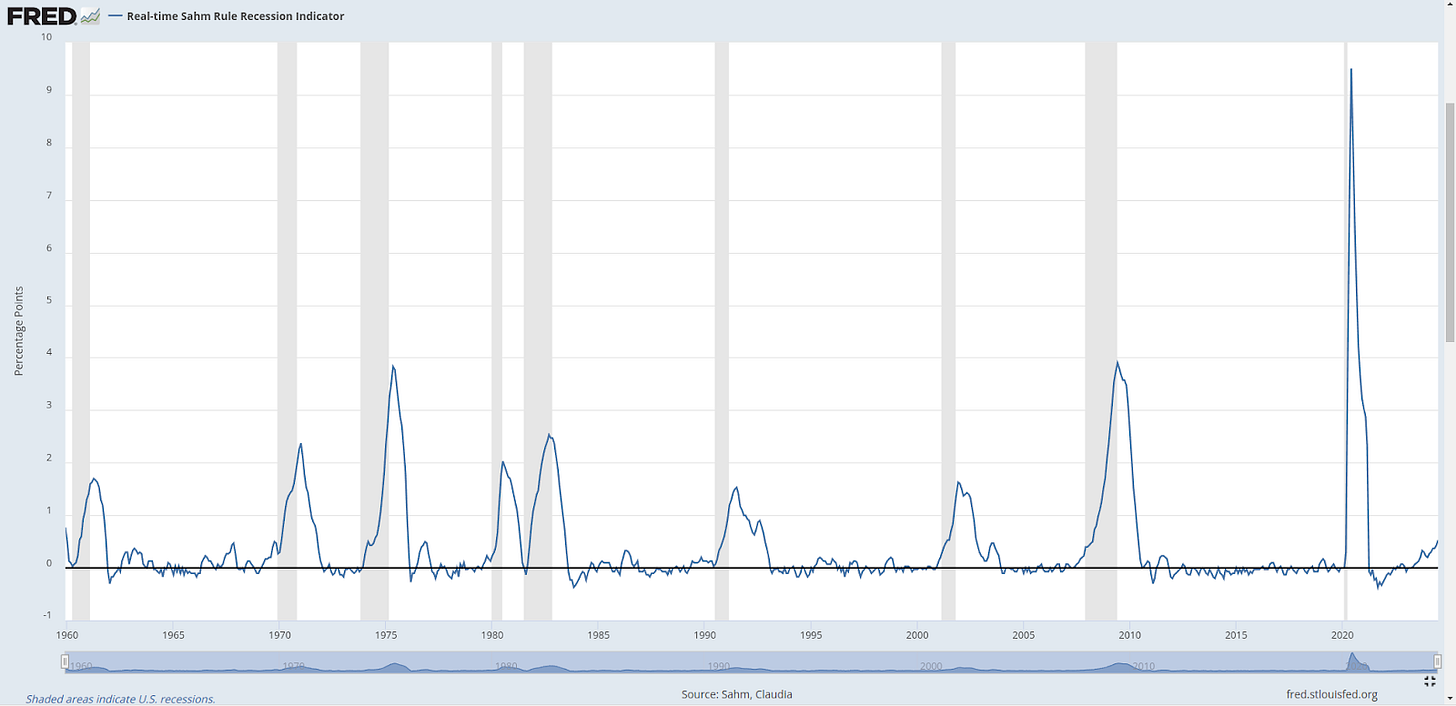

Last week, the US jobs data came in, and it was disappointing. The US unemployment report hit a high last seen in October 2021. This bad jobs report sparked fears that the US is at a high risk of recession if it’s not already in one. This report also triggered something called the “Sahm Rule.”

Let me explain. The Sahm Rule is a recession indicator created by Claudia Sahm, a former economist at the Federal Reserve. It says that the US economy will be in a recession when the three-month moving average of the national unemployment rate rises by 0.5 percentage points or more above its low during the previous 12 months. Sahm used the unemployment rate because once it starts rising, it tends to keep rising, as bad economic momentum feeds on itself. If the unemployment rate keeps climbing, it means the economy is in bad shape and likely in or entering a recession.

So why am I talking about this? When sentiment is bad, people expect the markets to stay bearish and often look for confirmation signals. The fact that the dominant sentiment is bearish right now means people are picking up on indicators like the Sahm Rule to confirm their bearish bias.

Source: FRED

But is the Sahm Rule wrong? Even Sahm herself wrote that “The Sahm Rule is a historical pattern, not a law of nature.” She also recently said that a recession is not imminent, even though the Sahm Rule is close to triggering. She pointed out that the rule is likely overstating the labor market's weakening due to unusual shifts in labor supply caused by the pandemic and immigration. While the risk of a substantial weakening or a recession in the next several months is elevated, this adds to the case for the Fed to begin cutting rates.

So, yeah, you can’t just take one indicator and predict a recession.

Another recession indicator that’s getting attention is the US yield curve. A yield curve is a graph showing the relationship between interest rates and the time to maturity of debt for a given borrower, usually a government. It plots the yields of bonds against their maturities, ranging from short-term to long-term. Changes in the yield curve shape give insights into investor expectations about future interest rates, economic growth, and potential changes in monetary policy.

Typically, a normal yield curve is upward sloping, meaning that longer-term bonds have higher yields compared to shorter-term ones. This suggests a healthy economy. But sometimes, a yield curve can invert, meaning short-term government bonds have higher interest rates than long-term bonds, which sounds weird, right?

Well, the US government bond yield curve has been inverted since 2022. A 10-year bond pays more than a 1-year bond. Why? Because the US Fed hiked rates massively, pushing short-term bond yields higher, while investors expected inflation to fall and the US to enter a recession, pushing down long-term bond yields.

Source: US Treasury

An inverted yield curve is seen as a recession indicator. Historically, recessions have occurred anywhere between 6-24 months after the yield curve inverts. It’s been 23 months since one part of the yield curve inverted, which probably explains why this indicator is in the news.

Interestingly, the yield curve inversion doesn't have the same predictive power for recessions everywhere. It’s stronger in advanced economies and weaker in emerging markets like India. In fact, the Indian government bond yield curve was inverted earlier this year, and we aren’t in a recession.

But back to the US yield curve. Some experts now say it’s not the inverted curve that predicts a recession but rather the curve un-inverting. This means when an inverted yield curve becomes normal again, it predicts a recession. One analysis suggests the time between a curve un-inverting and a recession is about 66 days. Right now, the US 10-year treasury bond minus the 2-year treasury bond is close to un-inverting. This means the 2-year bond has been yielding more than the 10-year bond, which is abnormal, but the situation is normalizing.

Source: FRED

This is causing worries that this disinversion predicts a recession, just as people are screaming that the US is entering or already in a recession. Economic indicators are never perfect. As a statistician famously said, “All models are wrong, some are useful.” That’s a perfect way to think about this. People who are bearish will use any available evidence to confirm their pre-existing biases. That’s what’s happening here. The bear wants bearish evidence.

This doesn’t mean the US economy isn’t in trouble. But if you’re a long-term investor, you don’t have to be spooked by this and sell everything.

You will now get bonus faster

SEBI recently put forward a new proposal to streamline the allotment of bonus shares for investors. The aim is to tackle current issues and introduce a standardized approach. But before diving into the details, let's set the stage with how things currently work.

Right now, when a company announces a bonus issue, it goes like this:

The board approves the bonus issue.

They set a record date to determine who gets the bonus shares.

The shares are then credited to the eligible shareholders' accounts.

Finally, the new shares start trading.

It sounds straightforward, but there's a catch—there’s no uniformity in the process. Some companies get everything done within 15 days, while others can take up to two months. This inconsistency exposes investors to unnecessary market volatility.

SEBI's new proposal is to introduce a T+2 day allotment timeline for bonus shares. Here’s how it breaks down:

On T day (record date): Bonus shares are allocated to those who are eligible.

On T+1 day: Shares are credited to the account of eligible shareholders.

On T+2 day: Trading begins with the revised price.

Additionally, companies will need to apply for in-principle approval from the stock exchange within five working days of their board’s approval. This will create consistent timelines for all companies, no matter what.

Why is SEBI doing this? It's pretty simple:

It cuts down the time between the record date and when trading starts, reducing investors' exposure to market volatility.

It makes the whole process more predictable for investors.

This proposal, if implemented, can have a positive impact on the markets. Let me explain with an example:

Imagine a company sets January 1st as the record date for a 9:1 bonus issue (9 shares for every 1 share held). You buy one stock of that company for 100 rupees on January 1st, making you eligible for the bonus shares.

Under the current system, on January 2nd, the stock would start trading at 10 rupees instead of 100 rupees because of the bonus issue. In theory, this is fine because you now have 10 shares instead of 1, so your total value remains the same. But here's the catch: the 9 bonus shares might take some time to appear in your demat account, and there's no clarity on how long this will take.

So, for a while, you're stuck with just 1 share out of the 10 you own, and you can’t sell the other 9 even if you wanted to. That’s not ideal.

SEBI’s proposal aims to fix this. With the T+2 days rule, the waiting period is reduced. So in our example, you'll get your remaining 9 shares by January 3rd—just 2 days after the record date.

If SEBI implements this rule, it will provide more protection and stability for investors, making the process smoother and more predictable. All in all, it’s a smart move to keep the market fair and efficient for everyone.

I want this job

Uesss