The world's new energy order, in five stories

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The world’s most critical energy stories

Emerging markets wade through a sea of Chinese EVs

The world’s most critical energy stories

If you want to understand the direction in which the world is headed, you should know what the International Energy Agency, or the IEA, is thinking. The body is, in a sense, the world’s energy watchdog — everyone from governments to businesses tune into its latest analysis on the world’s energy markets.

The body’s flagship yearly report is called World Energy Outlook, and it is arguably the world’s most authoritative breakdown of where its energy system is headed. The latest edition came out just a few days ago. It’s a 500-page behemoth, and we can’t possibly tell you everything it contains. But here are five critical trends that the report identifies.

The world is more energy-hungry than we hoped

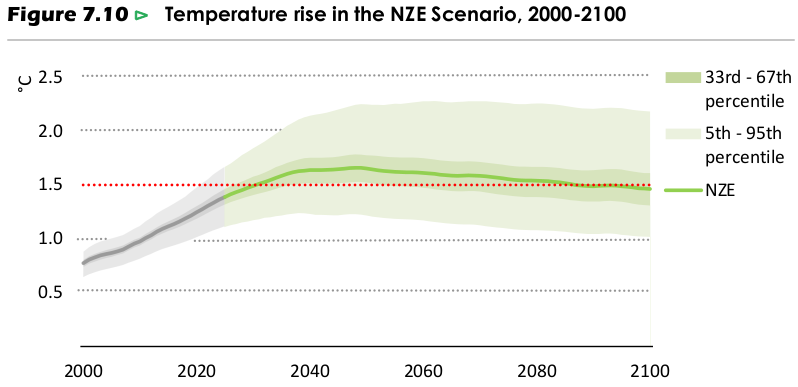

There’s a dark reality we need to come to terms with. We have no real hope of arresting global warming at 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

Frankly, all our hopes of doing so hinged on an ideal scenario: where our dependence on fossil fuels would peak soon, and then fall off, as we quickly moved to cleaner sources of energy. Every year since 2021, the IEA created scenarios that mapped what was needed to meet this goal. Each year, those scenarios were more drastic than the last. This year, to the IEA, that door has shut. Its best case scenario, now, we shall hold average temperatures down to 1.65°C.

The world, it seems, is more energy-hungry than we hoped. Global energy demand seems to have moved 4% higher than we expected a single year ago — from air conditioning to data centres, our energy demand has surged faster than we hoped. Meanwhile, neither have we ramped up our renewables capacity fast enough to meet this demand, nor is our energy efficiency growing as fast as we need. And Trump’s policy reversals, alone, have hurt our prospects significantly.

The result? Our use of fossil fuels will peak much later than we hoped.

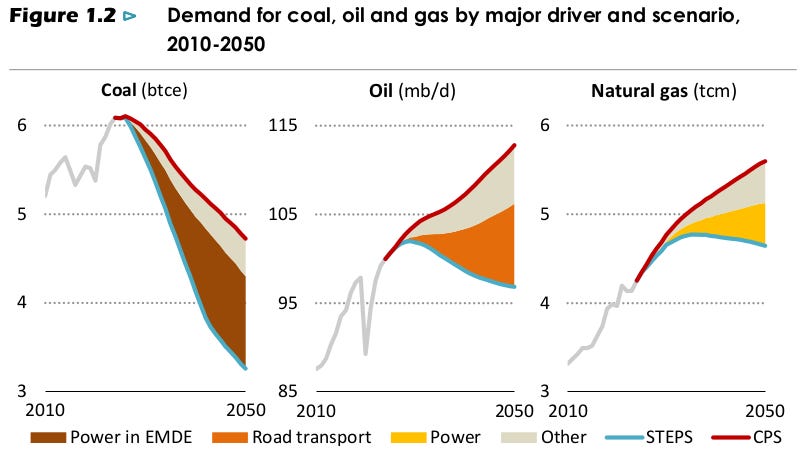

There are two scenarios that the IEA looks at to understand our trajectory. The first — called ‘STEPS’ — tries to predict what happens if countries follow through on all the announcements they’ve made. In that rather optimistic case, our use of coal now peaks before 2030, oil around 2030, and natural gas around the mid-2030s. This is all later than previous forecasts. The second scenario — ‘CPS’ — looks at what happens if we continue with our current policies. In this case, our use of oil and natural gas continues growing all the way to 2050.

Where does this leave us? By the year 2100, as things are going, average temperatures will be 2.9°C higher than pre-industrial levels. If all stated policies come through, and the ‘STEPS’ scenario comes to be, average temperatures rise by 2.5 °C.

If we hope to meet IEA’s best case scenarios, it’ll require brutal cuts — slashing global CO₂ by 3.5 gigatons annually, for a straight decade without pause. That is twice the amount that our emissions fell during the height of the COVID pandemic, for ten times as long. And even then, we have a 20% chance of over-shooting the 2°C threshold anyway.

We’ve locked ourselves into a less-than-ideal future: one where plant and animal populations are irreversibly harmed, while sea levels keep rising for centuries. All we can do is to mitigate the damage.

The paradox at the heart of the “age of electricity”

Despite our reliance on fossil fuels, though, we’re evidently entering an “age of electricity.” More than one-fifth of the energy we use comes from electricity, and that is slated to increase to 25% by 2035. And if you account for the efficiency that electricity brings, the actual share is even higher.

But electricity has a severe supply chain problem.

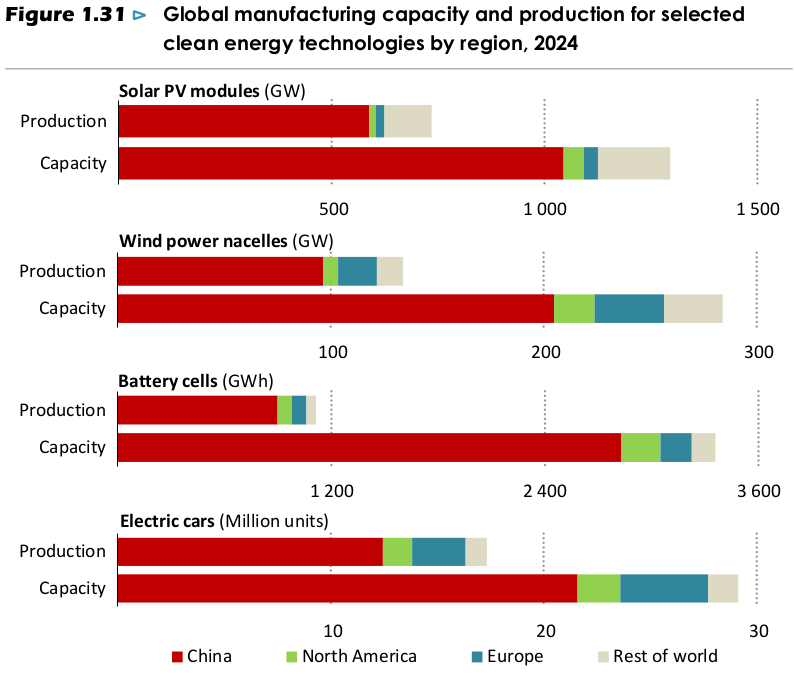

On one hand, we’ve built too much manufacturing capacity. Modern battery factories, for instance, are running at just 33% of their capacity. Solar panel makers, similarly, are stuck using half their capacity. A lot of this excess capacity is the result of China’s absurdly prolific build-out of green manufacturing.

Turns out, there’s such a thing as having “too much of a good thing”. While all this extra capacity drives prices down, it also crushes profit margins, pushing others out. While this overcapacity makes our green transition easier, it also concentrates the entire green industry in a single country.

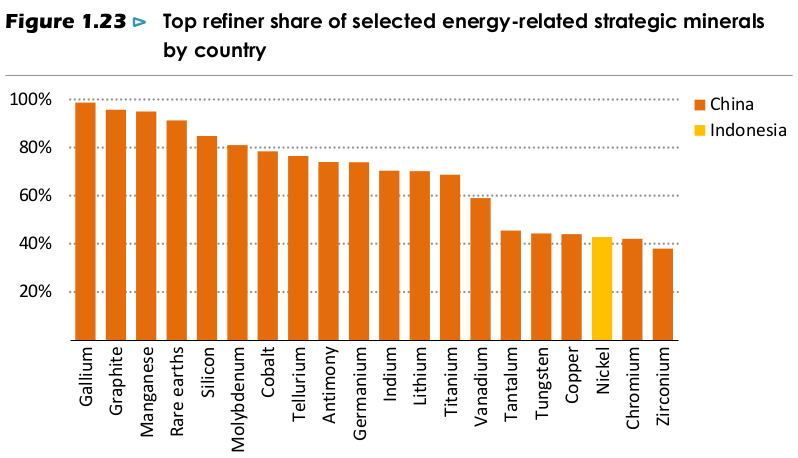

This dependence is even more dramatic higher up in the supply chain. Just three countries refine 86% of the world’s critical mineral supply. China is the unquestioned leader of this pack, with an average market share of over 70% in 19 of the world’s 20 most strategic energy minerals. For some, its dominance is total — like Gallium, where China refines 99% of the world’s supply.

This dominance, as we’re quickly learning, can easily be weaponised. When China put an end to its exports to its rare earth magnets, for instance, the entire world’s automotive industry — India’s included — came to a sudden halt.

This signals a profound shift. Not very long ago, countries viewed their “energy security” in terms of their ability to access fossil fuels. Energy-rich states would use energy exports as a weapon to browbeat others into submission — like Russia, which tried to gain political leverage over Europe by holding its gas exports hostage. India, similarly, has long defended its oil imports from Russia on grounds of energy security.

One would have imagined that things would change in the “age of electricity”. After all, there are now myriad ways of making your own electricity, that you can customise to your unique geography. This should have decentralised energy markets. As the IEA notes, however, the reality is the opposite. At least for now, all the minerals you need to harness this energy belong to a single country. The energy supply chain is more vulnerable to geopolitical pressure than ever.

Expect wild volatility ahead.

AI is a glutton for energy

One of the big reasons we’re more energy hungry than ever is the advent of artificial intelligence, and the infrastructure it requires.

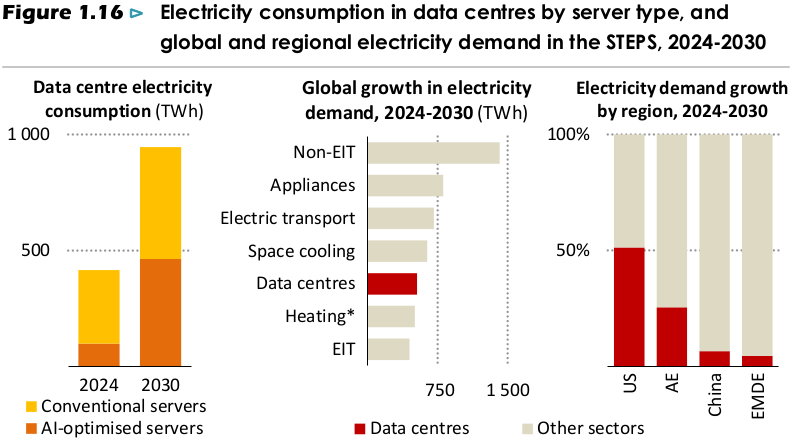

In 2025, global investment in data centers hit $580 billion. This exceeded the amount the world spent on oil — $540 billion — for the very first time. While data centres, in general, use heavy amounts of energy, AI-optimised ones are a different beast altogether. In just the next five years, these AI servers will increase their electricity consumption fivefold, which shall double the world’s total data center electricity.

But the amount of energy they consume, by itself, isn’t that big a problem. Over the next five years, globally, data centers will account for less than one-tenth of the extra electricity we need.

Then why are they so concerning?

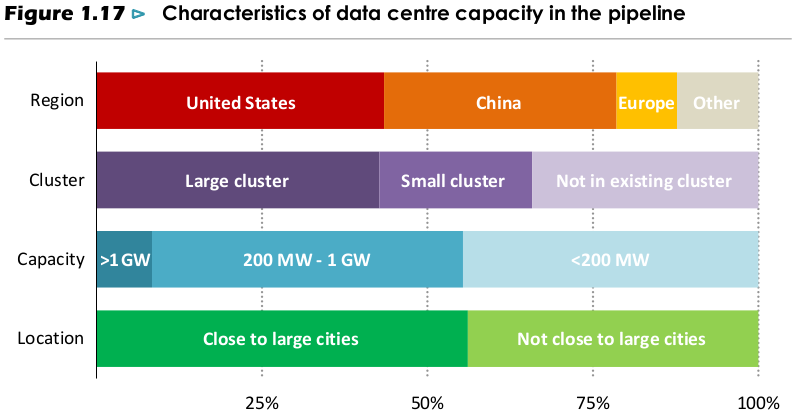

The real problem is geographical concentration. These data centres won’t be distributed equally across the world — they’ll cluster in small pockets. Currently, 82% of the world’s data centres are in the US, China, and Europe. Over 85% of the new additions over the next five years will be clustered in the same three regions. In the US, for instance, data centers will drive roughly half of the new demand for electricity until 2030.

Even in those regions, data centres won’t mushroom everywhere — they’ll only come up around a few select hubs. Consider the US state of Virginia, for instance. The state is currently home to ~35% of the world’s hyperscale data centres. And these drink up over a quarter of the state’s electricity. Residents of the state are already seeing their electricity bills sky-rocket, leading to severe political backlash.

So, while collectively, AI might only drive up a small part of the world’s energy demand, there are places where it could completely overwhelm energy needs. Half of the new AI data centres in the United States, for instance, need more than 200 MW — which is what 200,000 households need. In the clusters where these are coming up, they could easily overwhelm the grid, sparking a series of local energy crises.

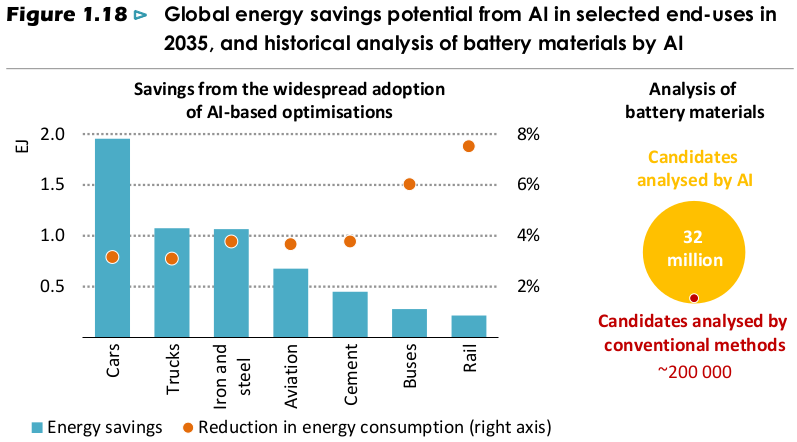

Interestingly, however, AI might eventually pay for itself — saving more energy than it consumes. IEA estimates that AI could eventually improve our efficiency in sectors ranging from transport to industry. By 2035, those energy savings could be as high as 13.5 exajoules, which is a little more than the entire power demand of Indonesia.

The grid is the bottleneck

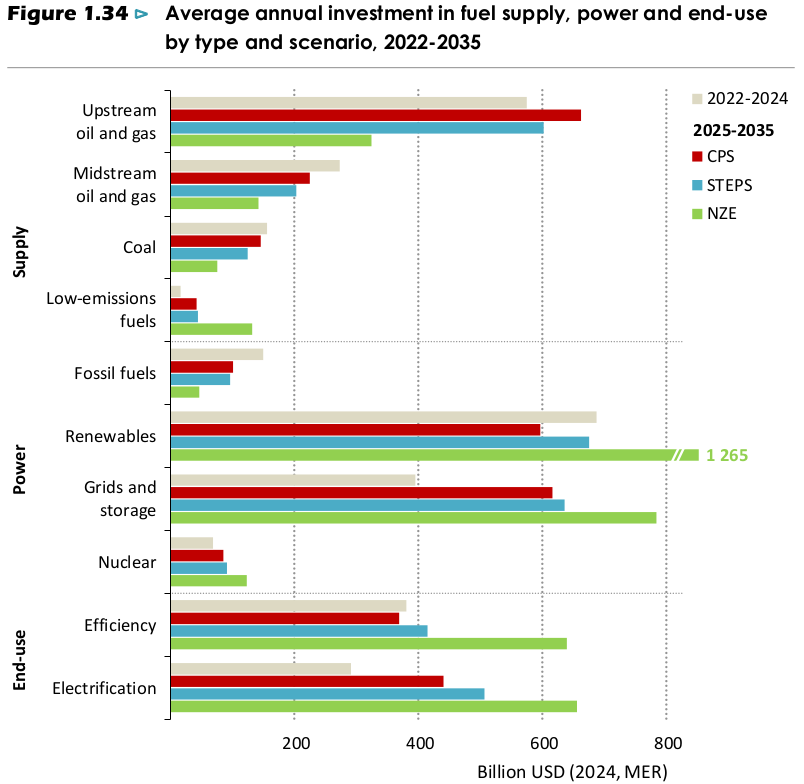

The world is generating power faster than it can produce the wires to carry it. Consider this: since 2015, global investment in electricity generation has surged 70%, reaching $1 trillion annually. Its spending on the grid, meanwhile, rose at less than half that pace — and now stands at just $400 billion per year.

This ratio is well below the historical norm. Ten years ago, utilities spent 60 paise on grids for every Rupee spent on generation. Today that figure is 40 paise.

There are clear consequences to this shortfall. Many renewables projects — roughly 2,800 GW of wind and solar projects, many in advanced stages — are stuck waiting for grid connections. Meanwhile, those that need power are facing major delays in getting connections. In parts of the United States, for instance, a new data centre can take as long as seven years to be connected to the grid. While there’s both demand and supply that’s waiting on the sidelines, we’re failing to link them together.

For those that are online, this grid congestion is driving up electricity prices. It’s also forcing the curtailment of clean energy, while we rely on dirtier, less efficient generators for our electricity needs.

If anything, we require a wholesale upgrade of our grid, to meet the demands of the “age of electricity”. To meet its imperatives, we need to grow the world’s grid to 110 million km — almost one-third longer than it is today — and replace another 20 million km of existing but aging lines. We also need electronic and digital grid management tools.This entails an investment of ~$650 billion every year until 2035.

But if anything, we’re struggling with the basics. The world is currently going through a severe shortage of transformers. High-voltage systems now come with wait times stretching into the 2030s. The prices of key metals like copper and aluminum are elevated. The workforce needed for this shift is thinning as well — for every young worker joining the grid sector, 1.4 are nearing retirement.

We’ve written about some of these problems before.

India could become the world’s new centre of gravity

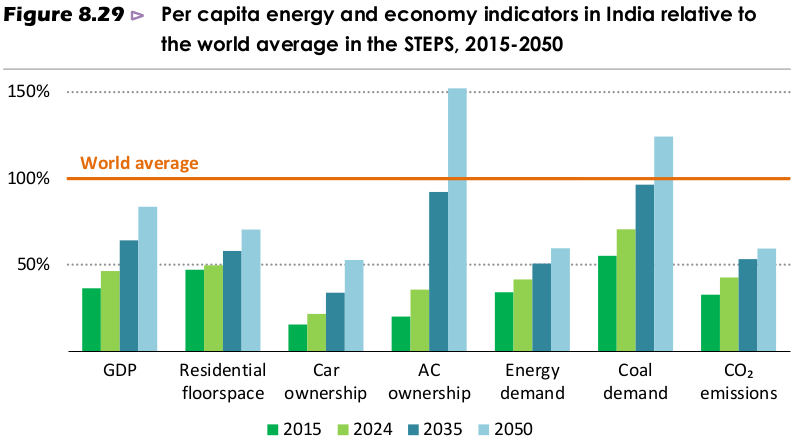

One aspect of the report caught our eye in particular: according to the IEA, India is quickly becoming the epicenter of the world’s new energy demand.

For decades, this role belonged to China. But its economy is starting to mature, and its energy appetite is stabilizing. Major drivers of new demand — such as the electrification of its vehicles — are beginning to plateau.

That baton is now passing to India, which has become the single largest source of new energy demand in the world. Over the next decade, the growth in India’s energy consumption will nearly equal that of China and all of Southeast Asia combined.

India leads the world in oil demand growth, driven by rising car ownership and expanding industry. We’re also the second-largest contributor to electricity demand growth globally. Coal use in Indian industry, alone, will jump 60% by 2035, as steel production nearly doubles.

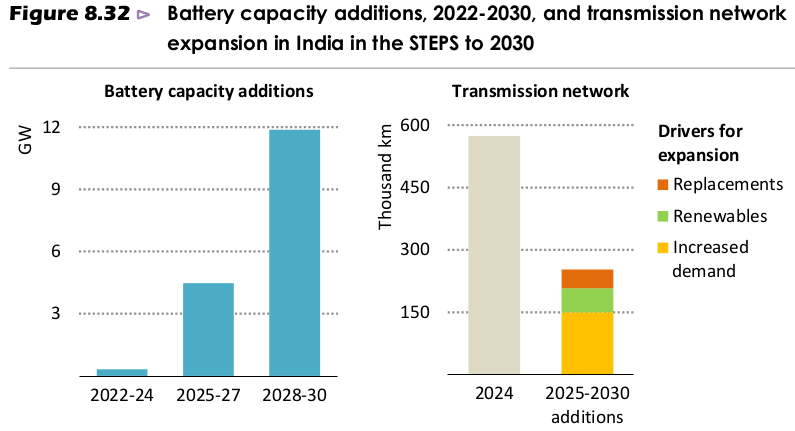

This surge in demand is sparking an infrastructure boom. We’re on track to build 200,000 kilometers of new transmission lines by 2030 — enough to circle Earth five times. We’re also adding massive battery storage facilities to manage our rapidly growing solar and wind power. By 2035, renewable energy will generate over half of India’s electricity, even as total demand grows 80%.

We’re not alone. Large parts of South-east Asia are also following this trajectory. Together, India and Southeast Asia could become the new epicenter of global energy consumption growth. The sheer scale of the build-out required to meet this demand will define energy markets for the next two decades.

Emerging markets wade through a sea of Chinese EVs

At Markets by Zerodha, some of the stories that excite us the most start with disruption.

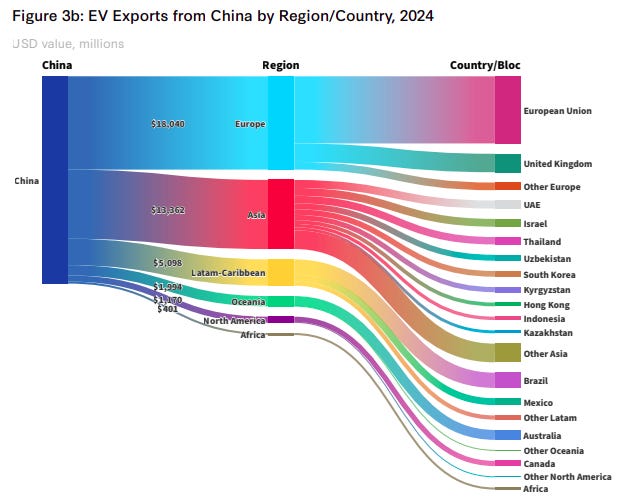

With EVs, the automobile industry is going through one of its most dramatic transformations since Henry Ford truly commercialized 4-wheelers. EVs are actively eating into the share of internal combustion engine (or ICE) cars, while also rewiring the entire supply chain of how cars are made and sold. At the center of this shift sits China, which now produces more EVs than the rest of the world combined.

But this shift, it seems, creates a dilemma for other developing, emerging markets. On one hand, Chinese EVs offer a shortcut to reaching net-zero climate goals. But on the other hand, this convenience comes with strings attached. What if, for instance, this creates a massive economic dependency on Chinese EVs, while also destroying domestic industries? This is a bigger problem for countries who have a tense history with China — like India.

This is what two researchers from CSIS, Ilaria Mazzocco and Ryan Featherston, explore in their latest report. They cover how multiple emerging markets — including India — are threading this needle. We’ll look into how these approaches differ, and how India is navigating this wave.

Let’s dive in.

The thesis

The core thesis of the CSIS report is that each country is using a unique mix of trade policy and industrial policy to increase EV adoption in their country.

What this means is that for EVs, each country has its own way of mixing tariffs on imports of Chinese EVs, and subsidies to increase domestic EV production. If you have zero tariffs on imports, then you can increase adoption a little faster, but it comes at the risk of destroying domestic capabilities. But subsidies for domestic production are an expensive affair, and can often lead to creating inefficient industries.

Neither tool is truly effective in isolation. In an earlier piece, we covered why this mix matters so much in the context of India’s solar industry. Each country wants to hit net-zero targets but on its own terms, without becoming entirely dependent on Chinese know-how. But they also would like to make use of China’s expertise to some degree.

What determines the right policy mix? See, if there’s anything true about policy, it’s that there really isn’t a one-size-fits-all answer to such problems. But the question you need to constantly ask is: what gives countries a bigger bargaining chip to make deals with China? That’s what determines their policy mix.

Through this report, we get a sense that there are three important factors. Let’s see what those are, and how India scores on each of them.

The charm of bigness

The first factor is size: how big is the domestic market for cars in the country?

CSIS finds that small countries that don’t really have a huge auto industrial base of their own lean way more on trade policy than subsidies. They are okay with not spending too much money to build their own industry. After all, it makes little sense to spend so much on having one’s own industry when the market itself is so small. Therefore, they’re okay with allowing imports at cheaper rates.

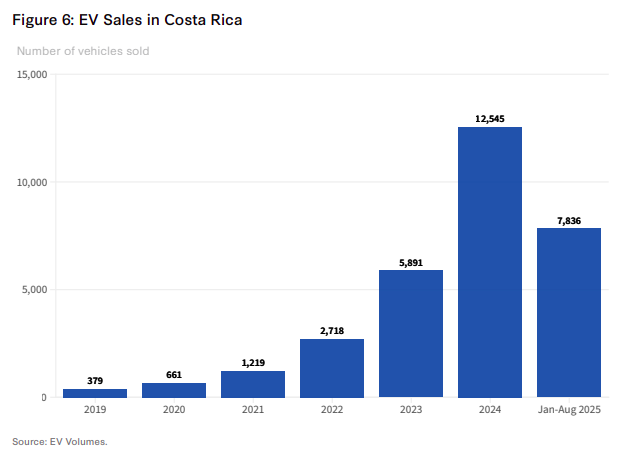

A key example of this is Costa Rica, whose population is just a little more than 5 million people — just about the population of the average Indian city. Not state, but city. The core city of Chennai, for comparison, is close to 7 million people.

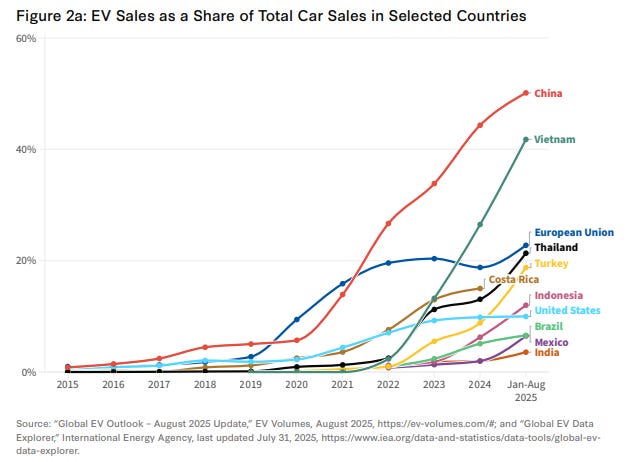

Costa Rica slashed import tariffs to near zero and watched EV sales jump 33x — from 379 vehicles in 2019 to over 12,500 in 2024. Or take Nepal, which saw EVs account for 76% of new car sales in 2024.

For both these countries, what CSIS also found is that their energy mix also mattered. Both countries want to reduce their reliance on importing oil, which can affect their foreign currency reserves. At the same time, they produce a lot of hydropower, a cheap and renewable source of energy which can be controlled better than solar or wind, and is therefore a reliable source of recharge for EV batteries. Costa Rica and Nepal see this as an opportunity to further phase out their oil imports.

But, once you zoom out from a small to a big country, the calculus flips. Countries like Brazil and Indonesia have the scale for domestic production. In these countries, auto manufacturing already accounts for 5-6% of GDP and employs millions. Opening the floodgates to Chinese imports could devastate existing industries and wipe out any advantages they already had.

So, they use this scale as a bargaining chip. Indonesia, for instance, temporarily removed import tariffs for companies that committed to establishing a factory within Indonesian borders. To ensure compliance, the government forces firms to put up the same amount of money waived as tariffs, which can be seized if they don’t follow through on their commitment.

Perhaps no country is a better example of this than the most populous country in the world — ours. India has a huge auto market, selling 43 lakh passenger vehicles last year. And the size of the market alone lends India a huge leg up when it comes to deals with China. This advantage allows us to put strong tariffs on their EVs, which is coupled with incentives for both domestic and foreign carmakers to invest within India.

Take India’s new EV policy — which we covered in our episode on Tesla’s entry into India. Much like Indonesia, we also demand commitments from foreign firms in lieu of lower tariffs, as well as a large deposit that can be seized if commitments are not met. Our commitments, however, are stricter than that of Indonesia — and being the most populous nation in the world certainly helps us call such shots.

But relying on size alone as a determinant of what kind of policy can lead you to weird places. Take Mexico, for instance. It is Latin America’s second-most populous country, and has a huge auto industrial base. But its own domestic market is really small — in fact, most of the cars it makes get exported to the US.

How does one explain this puzzle? For that, we should look at the second factor: how a country is currently integrated into the global auto supply chain.

Integration in global supply chains

The EV value chain sprawls from lithium mines to battery cells to final assembly to even the software required by EVs. It has a lot of overlap with the ICE supply chain, and no country truly controls it end-to-end. They all have their own specializations and structures that they could potentially use to get a leg up in the new EV wave.

Take Indonesia, for instance. As the world’s largest reserve of nickel — which is a key element in today’s EV batteries — Indonesia is a huge chokepoint for the world’s auto supply chain. In fact, it has used it to that degree by banning all raw nickel ore exports, so that it can develop its own capacity to refine nickel and also make batteries.

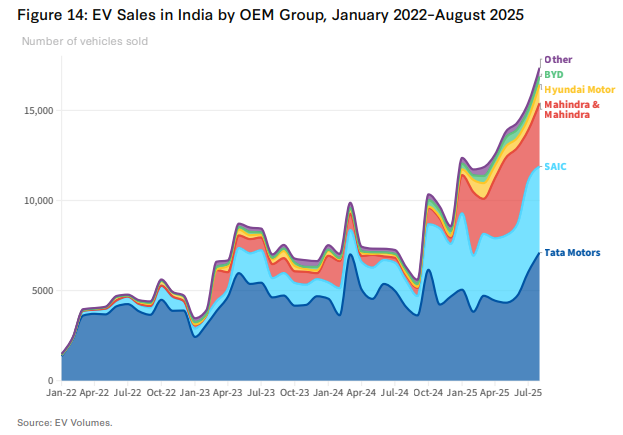

What about India? Our strategy is a bit similar to that of Indonesia — integrate into the global chain, but not at the cost of sovereignty. Indian brands like Tata and Mahindra hold most of the domestic EV sales. We’re also a world leader when it comes to making car software, with firms like Tata Elxsi and KPIT leading the way. We also export over $20 billion worth of car parts every year. India uses this strategic integration to also invite foreign auto investments — especially from friendly partners like Japan and South Korea.

However, how countries have chosen to integrate themselves in the chain comes with risks. And the trade-offs lie both in too much integration, as well as too little.

The CSIS highlights Mexico as a case of why high levels of integration isn’t always good. Its auto industry, CSIS highlights, was deliberately designed to mostly export to the US — on whom it’s highly dependent for auto investments. But it is barely able to supply to its domestic market and doesn’t have a strong car brand of its own. Additionally, Mexico mostly does car assembly, and hasn’t been able to move into higher-value tasks like auto R&D. In fact, because its auto industry can’t supply itself, Mexico has been importing a lot of Chinese EVs.

But on the other hand, insulating oneself heavily from the world is not such a good idea, either. The risks are high back home, too. India’s EV adoption rates have been really slow compared to Indonesia, Brazil, and even Costa Rica. And despite our tariffs, we still depend heavily on Chinese imports for batteries. We’ve covered why India’s import tariffs — some of the highest in the world — have often insulated us from the cutting edge across industries.

Or take Brazil as well. It is a pioneer in flex-fuel cars (or FFCs) that use lots of ethanol — of which it’s also the largest producer. However, its policy for net-zero cars, MOVER, doesn’t truly incentivize EV adoption much more than FFCs. The reason, it seems, is because EVs would wipe out FFCs, and as a result, a huge chunk of the ethanol industry, which employs millions of Brazilians. However, EVs today are far more efficient than FFCs.

That being said, India’s case is more complicated. We don’t just insulate from foreign competition to sustain our domestic industry. We have to because of who the competition is.

Entertainment, entertainment, and geopolitics

This leads us to the third factor: geopolitics. For several emerging markets, the Chinese EV surge collides with security concerns. And India faces the starkest such tension, having a long history of conflict with China.

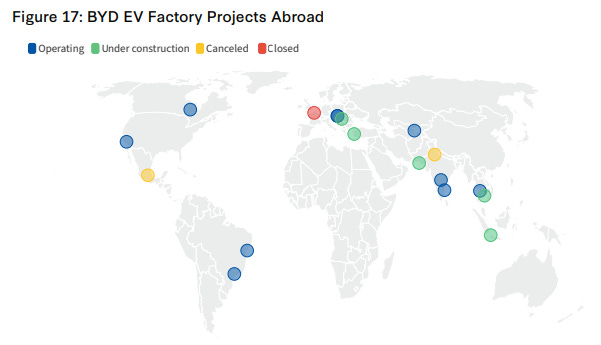

As a result, India has adopted an extremely-cautious approach to Chinese EV investments. For instance, India blocked BYD’s $1 billion factory proposal in 2023 on security grounds. SAIC’s joint venture with JSW Group is being restructured to dilute Chinese ownership under government pressure.

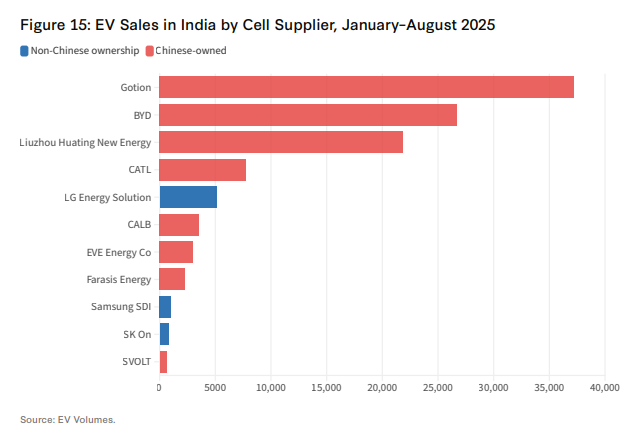

However, India is also finding it next-to-impossible to build a value chain that doesn’t depend on any kind of Chinese investment. Though BYD doesn’t sell a lot in India yet, it is the primary battery provider to Mahindra’s EVs. Tata, meanwhile, relies on Chinese firm Gotion for its batteries. In fact, India recently reduced tariffs on batteries imported from China.

Even Mexico is in a bind. Its closeness to the US means that the US is heavily concerned about the rise of Chinese EVs in Mexico — or even those EVs entering the US through Mexico. When BYD floated factory plans in Mexico, American political backlash was swift. By mid-2025, BYD shelved those plans, explicitly citing trade tensions.

Any discussion about collaborating with China in any capacity is not merely a question of economics — security takes up as much importance. Even Brazil and Indonesia, while not having any such active conflict, are worried about Chinese dominance, and try to gain leverage through their domestic strengths.

Mad, mad world

The rise of Chinese EVs has opened up new opportunities (and threats) for emerging markets who want to make use of this technology for themselves. And we’re still learning how many of them adapt to this new paradigm differently. But we do see some common themes emerge across the size and scope of various countries.

India’s strategy is complicated not just by its pursuit of a sovereign economy, but also its unique history with China. While we have size and presence across the auto value chain, our tariffs can insulate us from innovation. And while it is important to be on-guard with China, is it really wise to not make use of any Chinese know-how?

These are questions with answers that are neither easy nor static in time. But what does matter is continuous evaluation of what’s working, and changing tack accordingly.

Tidbits

India’s smartphone shipments hit 5-year high

India’s smartphone market rose 4.3% YoY in Q3 2025 to 48 million units, the highest in five years. Apple logged record shipments of 5 million iPhones, driven by strong demand for the iPhone 16 and 17 series. Premium models led growth, while mass-market sales stayed weak due to rising costs and inventory buildup.

Source: Economic TimesCanada, India restart trade talks

After a two-year diplomatic freeze, Canada and India are restarting trade negotiations under a “new process,” focusing on critical minerals, clean energy, AI, and agriculture. Canadian Trade Minister Maninder Sidhu said the thaw follows PM Modi’s meeting with PM Carney and that both sides aim to expand investment and cooperation.

Source: ReutersSEBI plans to ease pre-IPO lock-in rules

India’s market regulator SEBI proposed reducing lock-in restrictions for pre-IPO shareholders (excluding promoters and major investors). The move aims to simplify listings and speed up share releases. The plan follows a record $16.5 billion raised via IPOs this year amid growing concerns over inflated valuations.

Source: Economic Times

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Manie.

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉