The wires & cables industry is all charged up

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The wires & cables industry is all charged up

Indigo wants to fly higher — but can it?

The wires & cables industry is all charged up

A few months ago, we broke down how the wires and cables (W&C) industry works through its strong Q1 results. That solid streak, it seems, has continued into its latest Q2 results.

W&C is an industry that we rarely think about, but activity here tells us about what’s happening in many other sectors of the economy. More importantly, though, India’s W&C firms are bracing themselves for change. They’re preparing themselves for new sources of demand while deprioritizing other lines of business. At the same time, as we covered before, new blood backed by tons of capital is entering the industry.

Change, they say, is the only constant, and that’s the story that comes out to us through their Q2 results. So, let’s dive into the results of Polycab, KEI Industries, RR Kabel and Havells, to see how this industry is changing.

The numbers

All four players posted strong growth in Q2, both on an annual and quarterly basis.

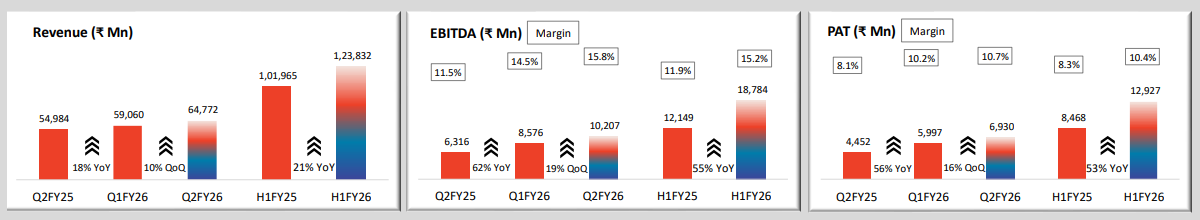

Polycab, the undisputed industry leader, has continued its impressive show-out. At ₹6,477 crore of revenue, it is up 18% from the same time last year. Its growth in profit-after-tax (PAT) was even more impressive, jumping by 56% from last year. With this performance, Polycab has recorded its best-ever second quarter, and its best first half of any year.

In other words, the biggest company in the sector took an even bigger lead in the race.

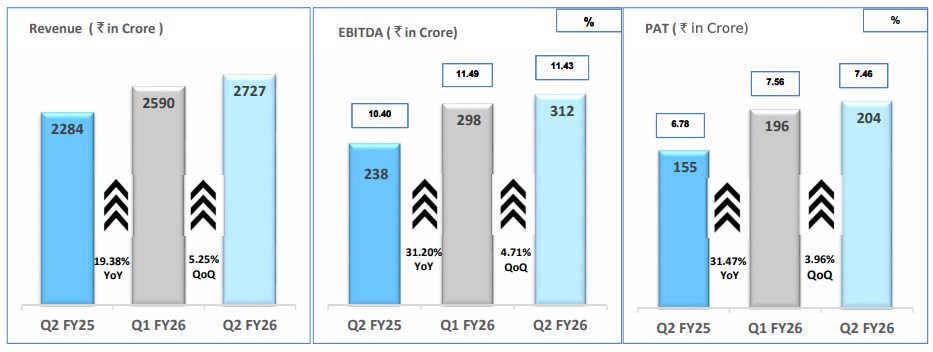

But KEI Industries was no slouch, either. Its revenue grew by 19% y-o-y to ₹2,726 crore, with PAT up 31% y-o-y. While its PAT margins are lower than that of Polycab, they have improved this quarter.

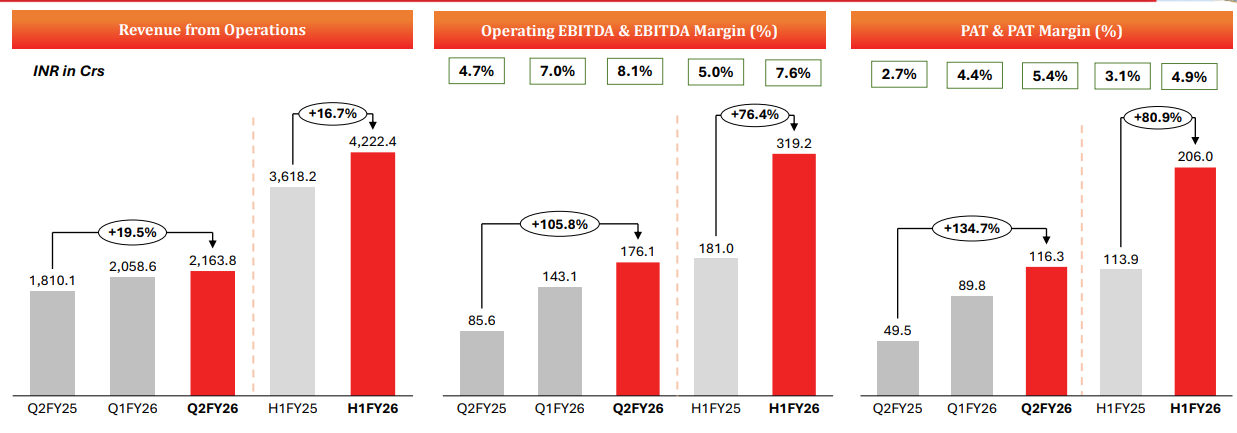

RR Kabel — the relative upstart that went public just 2 years ago — saw its revenue rise 19.5% y-o-y to ₹2,164 crore, while its profits more than doubled from last year. Its PAT margin, while thinner compared to KEI and Polycab, has also bounced back. This was also RR Kabel’s best first half of any year.

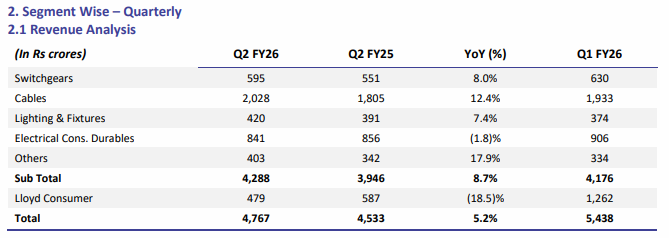

Havells, with its broader consumer portfolio, grew more modestly at 5.2% to ₹4,767 crore. But within its portfolio, the W&C business in particular grew 12% y-o-y to over ₹2,000 crore. It is one of their fastest-growing segments. For W&C alone, their PAT has grown ~1.8x from last year.

Remarkably, across the board, margins held steady despite volatility in the prices of copper — which is used to make wires and cables. Copper prices had spiked earlier in the year, but companies used various strategies to combat this risk. For instance, here’s Polycab talking about it…

…while KEI hedges against this with some extra copper inventory and clauses in their contracts to pass on higher costs:

Cables over wires?

The growth of the W&C industry has many nuances. The biggest of them is that lately, the C is taking a much bigger share of the space than the W.

If you’ve read our primer, you know this distinction matters a lot, but we’ll recap it again. “Wires” are used in simple, everyday applications like lights and fans. “Cables,” on the other hand, often mean higher-voltage products used for industrial uses, and therefore sold mostly to institutions, businesses and the government. Most importantly, though, cables command better profits per unit than wires.

This distinction tells us plenty — like what the new sources of demand are (or will be in future), how these products are evolving, and even which industries in India are among the fastest-growing.

Take KEI, for instance. Its extra-high voltage (EHV) power cables performed extremely impressively, jumping 76% year-on-year from ₹73 crore to ₹128 crore. They have an EHV order book of ₹636 crore. The demand is coming from the new-age renewable energy sector: think solar and wind farms.

And they do not expect renewable energy (which benefits plenty from government subsidies) to slow down anytime soon. If anything, it might go into overdrive.

Another new source of demand for KEI has lately been data centers, which obviously require tons of cables that can transmit data at nothing less than lightning speed. Cabling makes up 8-9% of the cost of a data center, and KEI fully intends to cash in on this opportunity.

Polycab’s premium cables business is playing a slightly different game. They have a special purpose cables (or SPC) division which caters to EVs, defense and railways — the latter two are dominated by government projects. Polycab’s SPC line benefits massively from the government ensuring demand for their products.

Even RR Kabel and Havells, which have traditionally been stronger in house-wires, are slowly making a pivot towards cables.

This shift towards cables is an interesting proxy for how India’s economic trajectory is shaping up. Be it new-age industries like renewables and data centers, or government-priority sectors like defense and railways, a whole space of opportunity has opened up for the W&C industry. Moreover, demand from the bread-and-butter sectors of the industry — like real estate (both residential and commercial) and infrastructure — is still going strong.

To meet all this demand, we’re increasingly installing new capacity to make them in-house. That’s where we begin to talk about the capex plans of the W&C industry.

No cap on capex

W&C companies are pouring money hand-over-fist into capacity expansion, much of which is dedicated to high-voltage and specialty cables. They’re moving up the value chain to produce more complex, higher-margin products.

Polycab has embarked on a massive five-year plan to invest anywhere between ₹6,000-8,000 crore in its W&C segment. In the first half of this year alone, it spent ₹750 crore on new factories and technology upgrades for EHV/high-voltage cable capabilities. As for how important this capex could be: the management expects it to yield 4-5x revenue on the capex figure once facilities stabilize.

4-5x of ₹6,000-8,000 crores worth of capex. Let that sink in. For context, Polycab made ~₹22,000 crore in revenue last year.

KEI, while limited in size, is just as aggressive. This year, it has fueled ₹1000 crores into its new plant in Gujarat, which is primarily meant to make EHV cables. While the completion of the plant is delayed, it’s still expected to yield ₹3,000 crores in additional revenue once its first phase is operational.

Both RR Kabel and Havells are less detailed about their plans. But RR Kabel has planned a capex of ₹1200 crores over the next few years, 80% of which is meant for low, medium and high-voltage cables. Meanwhile, Havells will be investing ~₹1450 crores this year alone.

Where growth took a hit

While the results of the top W&C companies have been fantastic, they have also been marked by business lines that didn’t grow as much. Within that, two trends came out this quarter.

First, the sunsetting of EPC business.

Earlier, we had mentioned how EPC projects were increasingly making a lower chunk of the W&C business. In EPC contracts, the amounts tend to be large, but the margins are very low. EPC projects can also suffer cost overruns and payment delays. That’s why the top players are deliberately de-prioritizing it.

KEI, for instance, has practically put a cap on it. This quarter, EPC sales fell from ₹80 crore last year to a measly ₹47 crore — not even making up 2% of revenues. In fact, an analyst straight up asked them whether they’ll quit the EPC business, to which their response was this:

Meanwhile, RR Kabel doesn’t even have an EPC line, sticking purely to product sales.

Polycab, though, has a much stronger EPC segment. Yet, it saw a 19% decline this quarter in EPC revenues, primarily because of project timing. But they have also mentioned before that there isn’t much left to pursue in the EPC business.

Second, FMEG gets a rain-check.

Recently, many of the W&C companies have diversified into selling fast-moving electrical goods (or FMEG) like fans, lights, and switches, quickly becoming a fast-growing segment for Polycab and RR Kabel. However, this quarter, the division has disappointed across the board. Even for Havells, that’s easily the best-known among the 4 companies.

The culprit behind this was an unusually long monsoon that killed summer sales. Havells reported weak fan and cooler sales from a poor summer season. Similarly, Polycab couldn’t sell enough fans for the same reason.

However, as the results show, the FMEG business is not big enough for most of these players to dampen their tide.

An export boom? In the age of tariffs?

Something in the results that took us by surprise was the surge in exports. Our first question, of course, was, “how did exports boom like this with such steep tariffs levied against India?” Turns out, our W&C companies have played the export game quite smartly, diversifying where they sell.

RR Kabel is an export-heavy business, with 27% of its revenues coming from exports. The US makes up 8% of those sales. In August, finance chief Rajesh Jain bluntly said:

“I will not take any extra hit on my P&L statement just to make supply to the US”.

Instead, they have redirected volumes to their biggest markets in Europe and the Middle East, which together make up 75-80% of all their exports.

KEI’s export business also did very well this quarter, doubling from last year to an all-time high of ₹472 crore. Their exports are primarily going to Australia and the Middle East, as well as some presence in Europe and the US. In fact, both RR Kabel and KEI are hopeful that eventually, exports to the US will also stabilize and grow.

In the first half of FY26, Polycab also saw its export revenue rise 25% to ₹420 crore. They’re diversified across regions, including Europe, Australia, Middle East and South America. However, the US makes up 20% of their exports.

Indian W&C firms are clearly quite adept at navigating trade disruptions while also riding new industrial waves taking place internationally. Europe, for instance, is working on upgrading its energy infrastructure to renewables. The Middle East is on a construction spree with multiple mega-projects. Even Africa is electrifying.

What it all means

For W&C, the second quarter of this year has been unmistakably upbeat.

They’re hoping to surf multiple waves that are currently in their favor. They’re ready to move up the value chain and are investing thousands of crores each year in service of that goal. All the while, they are actively pruning out the parts of their business (like EPC) that carry too much baggage without yielding much return. They’re combining ambition with discipline, and they’re doing it really well.

If their big bets pan out, we could see several more quarters of such electrifying performance from them.

Indigo wants to fly higher — but can it?

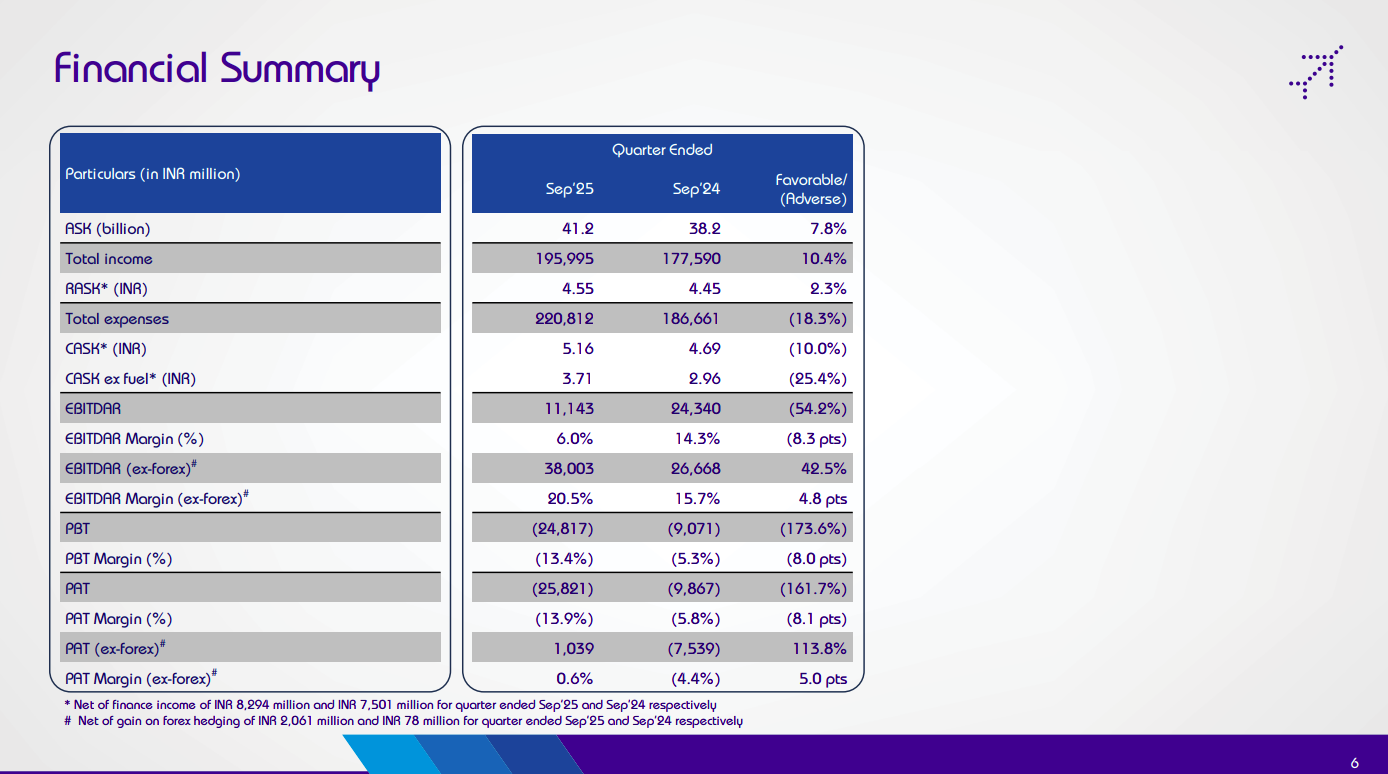

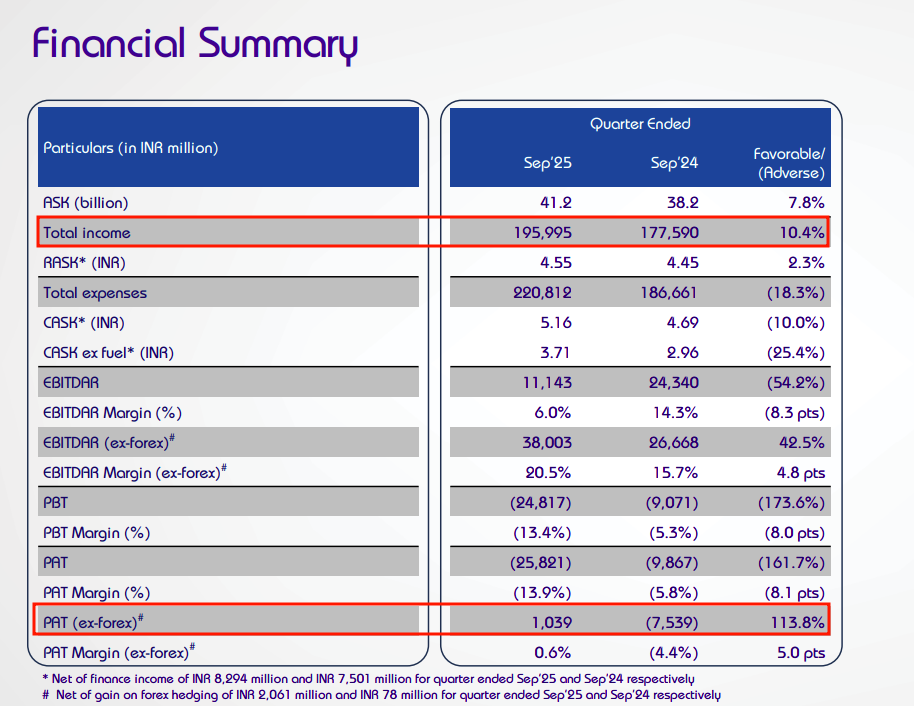

Indigo, by far the largest airline in India, recently released its 2nd quarter results. The results look….weird.

It delivered a ~10% revenue jump, but made a whopping ₹2,580-crore loss. On paper, this would normally spell disaster. But the reality, of course, is a little different.

Let’s dive into what Indigo’s results really say.

The profit paradox

For IndiGo, July-September is usually the soft quarter. This quarter, the rains get heavy, while also having fewer holidays and slower business travel. This year, though, the story flipped: the underlying business was healthy, but a sharp rupee fall turned an operating profit into a reported loss.

IndiGo earned ₹19,600 crore in revenue, ~10% more than last year, and actually managed to turn an operational profit of ₹104 crore. And if there’s anything true about the airline business, it’s that making bank is really hard — in the same quarter last year, Indigo recorded a ₹750-crore loss.

So, how did a profitable quarter become a headline loss?

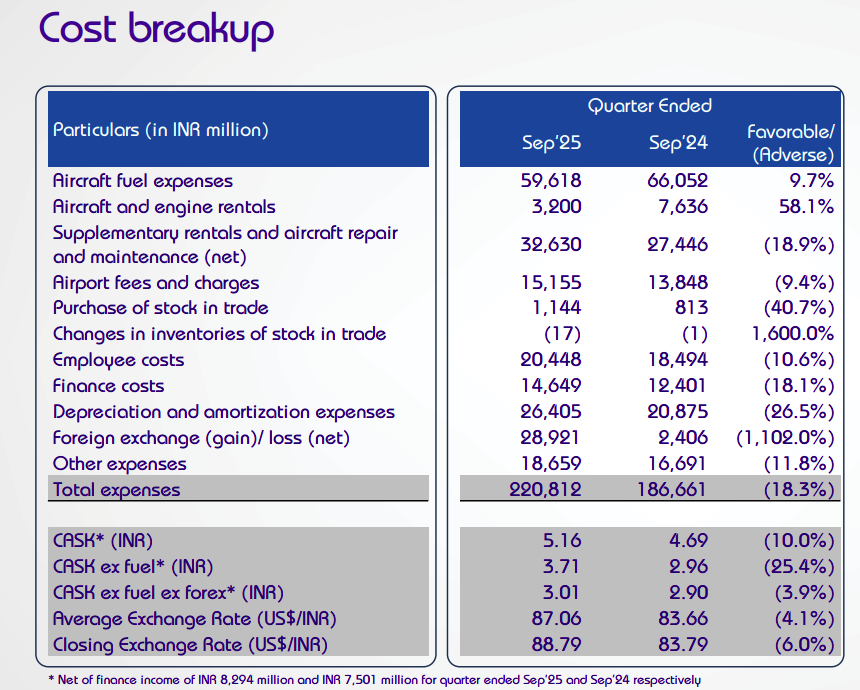

Well, because of accounting. More precisely, the rupee. IndiGo owes ~$9 billion in future payments for aircraft leases and maintenance contracts. These are dollar obligations spread over several years. Accounting rules require companies to “mark to market” these liabilities at the end of every quarter. What this means is that when the rupee weakens against the dollar, the math has to change. The currency fell by ₹3.18 against the dollar between June and September, so all those dollar obligations suddenly looked costlier in rupee terms.

“With a 3.18 rupee depreciation at the September quarter end as compared to the June quarter end, we ended up with around 29 billion rupees foreign-exchange loss under the foreign-exchange line item in the income statement.”

Nothing actually moved in cash. But on paper, IndiGo had to recognise a ₹2,900-crore foreign-exchange loss. The CFO explained it simply: every ₹1 that the rupee weakens wipes about ₹900 crore off IndiGo’s books. So this quarter, the airline lost money without spending a rupee more.

This is a reminder that in a dollar-denominated business like aviation, currency swings can decide whether you look like a success or a failure, even when the underlying business is fine.

The new playbook: from renting to owning

But what really made this quarter interesting wasn’t the forex loss. It was a major shift in how Indigo did business that was hidden in the fine print.

IndiGo has lived by the one motto: lease everything, own nothing. That’s what kept it nimble and scalable. But that model also left it deeply exposed to the dollar. Every rent cheque goes abroad, while every rupee of depreciation hits profit.

This quarter, like the past few quarters, management said they’re going to change that. By 2030, IndiGo wants to own or finance-lease 30–40% of its fleet — meaning more planes will sit on its balance sheet as assets, not just as rented equipment.

“Historically, we have operated with an operating-lease-heavy model. We are now actively transitioning towards a more balanced structure. By 2030, our goal is to have 30 to 40 percent of our total fleet held on our balance sheet, either in the form of owned or financed-lease structured.”

Right now, the airline has 417 aircraft, most of them leased from foreign lessors. But a growing number are now being financed through IndiGo’s own leasing arm in GIFT City, Gujarat’s financial hub. That structure lets IndiGo borrow in dollars at lower rates but still keep control — effectively paying rent to itself.

It’s not full ownership (yet), but it’s a step away from total dependency on foreign lessors — something we’ve covered before. The difference is simple: under a finance lease, IndiGo gradually pays off the aircraft, like an installment plan. At the end of the term, it owns the plane. That locks in lower long-term cost per aircraft and reduces the sting of currency volatility because more of the financing can be rupee-based.

As of September, IndiGo had 14 owned and 62 finance-leased aircraft, compared with virtually none a year ago. It’s a small start, but symbolically huge. The company that built its fortune on staying asset-light is now willing to take more on the balance sheet if it buys them stability later.

This shift doesn’t stop at ownership, though. IndiGo is also spending ₹1,000 crore to build a Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul (MRO) facility in Bengaluru. Right now, almost all of IndiGo’s heavy maintenance — the deep technical work that keeps planes airworthy — happens overseas. It’s costly and slow, and global MRO capacity has become stretched. Bringing that work home means shorter turnaround times, lower costs, and greater control.

It also fits the same logic as the fleet strategy: take more responsibility in-house, depend less on external suppliers, and build local capability.

Going long-haul

Indigo is also making an important addition to its arsenal: flying longer.

For nearly two decades, IndiGo has been the workhorse of Indian skies — short routes, high frequency, and on-time efficiency. It dominated domestic travel and operated in nearby international routes like Dubai, Singapore, and Bangkok. But its planes — the Airbus A320s and A321s — simply couldn’t fly much further.

But now, that’s changing. This quarter, IndiGo began its first-ever long-haul flights to Amsterdam, Manchester, Copenhagen, and London Heathrow, using leased Boeing 787 wide-body jets. These are its first twin-aisle aircraft — bigger, heavier, and capable of flying twice as far as the narrow-bodies that built the company.

And this isn’t a one-off experiment. The airline has ordered 60 Airbus A350 wide-bodies — double its earlier plan of 30 — with deliveries starting from 2028. Those planes can fly 12–15 hours nonstop routes (like Delhi–Tokyo, Mumbai–New York) that no Indian low-cost carrier has ever operated sustainably.

In the meantime, before the order arrives, IndiGo will use the Airbus A321XLR, a new long-range version of its familiar single-aisle workhorse. The XLR can fly up to eight hours, enough to reach Athens, Istanbul, East Africa, or Central Asia nonstop. That bridges the gap between short regional routes and the ultra-long ones that the A350s will eventually handle.

This is a huge strategic leap. For years, the company defined itself by discipline: fly short, fast, and cheap. Now it’s stepping into a long-haul market crowded with global giants like Emirates, Qatar Airways, and Singapore Airlines, who have spent decades perfecting the hub model. And even without the competition, long-haul flying is tough: as fuel is a bigger share of cost and crew duty times are longer.

But this leap also opens up something IndiGo never had: cargo capacity and dollar revenue.

Right now, more than 90% of India’s international cargo — like electronics, pharmaceuticals, textiles and so on — flies on foreign carriers. IndiGo’s narrow-bodies barely have space for baggage, let alone freight. A Boeing 787 or Airbus A350, on the other hand, can carry several tonnes of cargo under its passenger deck. Even a small slice of that market gives IndiGo new income in dollars, helping offset the same currency risk that hit profits this quarter.

Interestingly, while IndiGo was busy adding flights to London and Amsterdam, its domestic capacity barely moved this quarter. The airline faced multiple constraints: Delhi airport’s runway closure for maintenance, and delays in new airports like Navi Mumbai and Jewar.

Squeeze the most out of a seat

The easiest way to see whether the airline’s business model is sound is by zooming in on the economics of a single seat.

Passenger revenue per kilometre — or yield — rose 3% year-on-year. Planes were about as full as last year, with load factors around 83%. That means pricing held firm despite capacity additions across the industry.

On the cost side, fuel costs per seat dropped 16%, thanks to lower oil prices and the retirement of older, less-efficient leased aircraft. But non-fuel costs rose about 4%, largely because of rupee depreciation and lower domestic flying hours. When planes fly fewer hours, fixed costs — salaries, leases, maintenance — are spread over fewer kilometres, pushing unit cost up.

IndiGo now expects a low single-digit increase in unit cost for the year, instead of keeping it flat as earlier hoped. It’s not alarming, but it shows how much currency and operational hiccups can ripple through even the most efficient airline model.

Looking ahead

Indigo is expecting high-teens capacity growth in both Q3 and Q4 — one of its sharpest quarter-on-quarter jumps ever. Most of that expansion will come internationally, as new long-haul routes ramp up and China flights return. Domestically, growth will pick up once delayed airports open.

In fact, Q3 has already opened well, helped by an early Diwali and a surge in festival travel in October. IndiGo expects passenger revenue per seat in Q3 to be roughly flat or slightly higher than last year’s record high, which, given the heavy capacity additions, is effectively a positive signal for demand.

Indigo is not merely satisfied with being a low-cost carrier. It wants a global network, its own assets, maintenance capabilities, premium cabins, and long-haul reach. All ideally built on the same operational discipline that made it dominant at home.

The risk of such an ambitious bet, of course, is that margins don’t deliver in long-haul, or that exchange rate volatility keeps wrecking profits. But the opportunity is just as massive: to capture outbound travel, cargo, and connect India directly to the world. And IndiGo has the balance sheet, the cash, and the scale to try.

Tidbits

India’s inflation likely hits 10-year low: Consumer inflation in India is expected to have fallen to 0.48% in October, the lowest in at least a decade, driven by falling food prices and base effects from last year. Economists say the decline may be temporary, with risks of supply shocks from unseasonal rain and higher pulse import duties.

Source: Reuters

Hindalco injects $750 mn into US arm Novelis: Hindalco will invest $750 million in equity and raise debt for its US subsidiary Novelis to manage cash flow after a fire at its Oswego plant and rising costs at its $5 billion Bay Minette project. A second $1.5 billion phase is planned to double capacity to 1.2 million tonnes.

Source: Economic Times

Swiggy clears ₹10,000 cr fundraising plan: Food delivery giant Swiggy approved plans to raise up to ₹10,000 crore ($1.14 bn) via a Qualified Institutional Placement (QIP) to boost growth and fund new ventures in quick commerce. The firm has also sold its Rapido stake for $270 million and slowed warehouse expansion to improve margins.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Krishna.

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉