The new H1B rules take a hit at Indian IT

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

H-1B rules come for India’s IT industry

France's Debt Crisis: A nation at crossroads

H-1B rules come for India’s IT industry

For the last couple of decades, Indians have had their own version of the American Dream. If you learnt your way around a computer and worked hard enough, someone would lay a path for you to American shores. It was the dream — finding an employer that would fund your visa, letting you live a life that only the world’s richest country could offer.

Last week, that dream took a terrible dent. The US just hiked the one-time fee for all new petitions (but not renewals) of its most popular visa — the H-1B — from about $2,000-$5,000 to a staggering $100,000. Suddenly, simply trying to get to the US costs almost a crore.

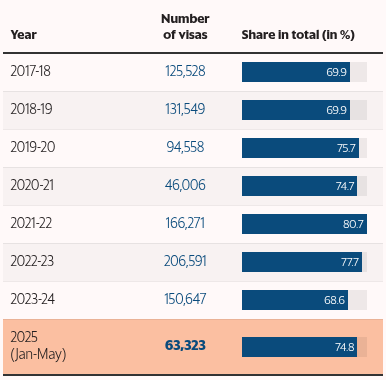

Nobody is as badly hit by this as Indians: we make for roughly three of every four H1-B visas that are granted.

But this doesn’t just hit Indians’ dreams of a better life. They might hurt our domestic IT services firms. They are, after all, some of the biggest recipients of H-1Bs in the world, with business models that rely heavily on these visas.

This is hardly the first time that Indians have suffered a shock from US visa rules, though — and Indian IT knows this all too well. This is, more than anything, a story of how businesses adapt to geopolitical uncertainty.

Let’s dive in.

The onsite-offshore model

Why do our IT companies rely so much on the H-1B visa?

Well, companies like Wipro, Infosys and TCS make most of their revenue from American clients. Most of what they do can be done from anywhere in the world — but there are a few tasks, from understanding client workflows to maintaining critical systems, that require their physical presence. And so, these firms deploy a few software engineers to client sites in America.

For many Indians, this was one of the biggest perks of joining such a company. An Indian software engineer that earned ~$30,000 annually in Bengaluru could, perhaps, find the opportunity of being embedded at a Fortune 500 company in New York. Apart from the experience, it would also net them a salary bump for the higher cost of living.

The IT firm, meanwhile, would bill $150,000-200,000 per year to their client — a good profit on each employee they sent.

This is called the “onsite-offshore” model, and it brought fat margins for Indian IT firms. The onsite team made up only 20-30% of the project team, while the rest were based out of India. This lets firms charge their clients hefty sums while paying relatively low labour costs for their Indian employees. Infosys, for instance, only has 3.3% of its employees on H-1B, but they generated 11.5% of the company’s revenue.

However, with the $100,000 fee, the economics of H-1B are completely broken. Unless you can see a profit per worker that is substantially above $100,000, there’s simply no point in attempting this route any more. This weakens the very foundation of the onsite-offsite model.

The Visa Maze

What made the H1-B so critical?

After all, the H1-B had its problems. Your visa had to be sponsored by an employer, who would have to pay as much as $5,000 to get you through. There was a cap on how many of them could be given out — and if there were more applicants than the limit, you’d have to win a lottery to get one.

But as we shall see, it’s better than the alternatives.

The first alternative is the L-1 visa, which allows for transfers within a company. It has no cap or lottery, unlike the H1-B. However, there's a catch: the visa only allows staff that have specialized knowledge of how their company works, and should be directly supervised by the US arm of their employer.

By the very nature of their work, Indian IT onsite employees don’t fulfil either condition. Indian IT firms have tried to illicitly use the L-1 as a substitute for the H-1B — a strategy called “body-shopping”, where generic programmers were tried to be passed off as having specialized knowledge. But that backfired spectacularly. Between 2012-14, for instance, 56% of all Indian L-1 visa petitions were declined to clamp down on body-shopping.

Then, there’s B-1 visas for business visitors. These are supposed to be temporary, meant for attending conferences or meetings that last a few days. Indian IT tried using B-1 visas to circumvent the caps of H-1B visas as well — only to learn, the hard way, that this was considered fraud. In 2013, for instance, Infosys paid a whopping $34 million settlement after being found they'd illegally used B-1 visas for onsite workers.

Lastly, there are O-1 visas, which actually have high approval rates and no annual cap. But they're reserved for genuine stars — think acclaimed researchers or award-winners. The average Indian software engineer hardly fits here.

The H1-B was the only legitimate visa that, until now, allowed for skilled immigration to the US at scale. You could relocate a generic worker, without special knowledge or genius, for up to six years. It was the only way the labour arbitrage model of an IT company made sense. They could sponsor thousands of H-1Bs every year while yielding good returns.

The Great Pivot

But does this simply rip apart the business of our IT industry? Not really. This isn’t their first rodeo. They’ve been here before, and are prepared.

US immigration policy, after all, has often been volatile. After 9/11, for instance, US visa issuance slowed down because of heightened security concerns. In 2009, the US implemented the “Employ American Workers Act”, which cracked down on outsourcing by making H-1Bs stricter. Under Trump’s first presidency in 2017, H-1B denial rates skyrocketed from 6% in 2015 to 24% in 2018. Then, after the COVID-19 pandemic, Indians would regularly have to wait for more than two years just to secure a visa appointment.

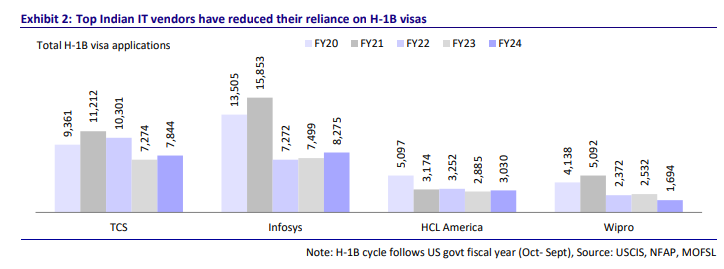

Which is why, over the last few years, Indian IT firms have consciously decided to decrease reliance on staffing Indians on-site. Instead, they either hire locals in the US, or convince the client to offshore more of their work to India.

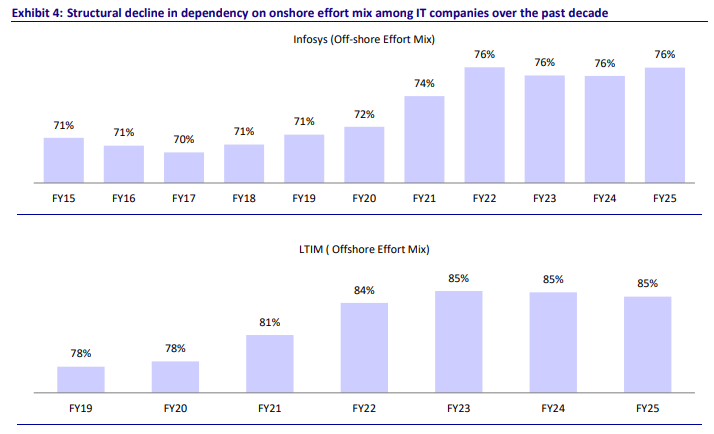

This strategy has yielded solid results. Infosys’s onsite staff on H-1B visas dropped from 30% a few years ago to 24% in FY25. 80% of HCL’s US workforce is now local hires — up from 70% a few years ago. Industry-wide, H-1B holders now make up just 3-5% of total headcount, versus well above 10% a decade ago.

Meanwhile, more client work is also being moved offshore. For some companies, what used to be a 70:30 offshore-to-onsite split has shifted closer to 80:20 — even higher.

And finally, India’s IT industry is also trying to diversify into regions other than the US — where their business model might have more stability.

Potential impact on margins

That said, what does this mean for the companies’ numbers?

Obviously, Indian IT won’t continue making the same number of applications, bearing a full cost burden of all of them. They’ll begin rationing visa applications for where it really makes sense. Because of this, many analysts expect the margin hit from new visa applications (due FY27) to be fairly low — 0.5-6% of the projected profit-after-tax in FY27. Companies may have to incur slightly higher costs for future visas, but it shouldn’t be something they can’t bear.

In fact, this could even be a net positive, primarily owing to offshoring more of the client work. CP Gurnani, the former CEO of Tech Mahindra, has said:

"We will do more offshoring, there will be more global capability centres (GCCs), and there will be more automation."

But there will be some companies who’ll have to seriously rethink how they do business. Analysts from CLSA, for instance, point out that mid-cap companies like LTIMindtree and Persistent Systems are more exposed than the largest IT companies, as they’re more reliant on earnings from H-1B staff than large firms. While those workers who already have a visa will be unaffected, it’ll be hard to send new workers to the United States. These companies will have to plan accordingly.

GCCs to the rescue

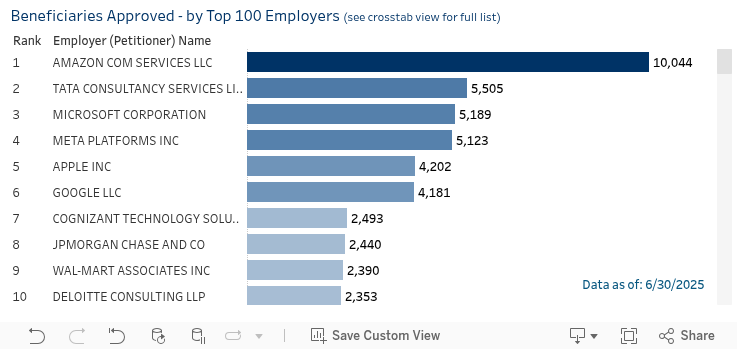

There’s another side to India’s outsourcing story: global capability centres (GCCs). Indian IT companies aren't actually the biggest H-1B users anymore. In FY24, US Big Tech companies got more H-1B approvals than the top 7 Indian IT firms combined. They, more than IT companies, might see their operations disrupted by Trump’s new policy.

But there’s a difference.

Unlike Indian IT firms, the Indian arms of GCCs don’t work for third-party clients — they build products of their own. MNCs create GCCs in countries like India to take advantage of lower labor costs and have them do low-value work. However, over time, these GCCs are increasingly doing more high-value tasks like R&D, becoming key hubs for MNCs.

Now, here’s the thing: US-based firms use H-1Bs to transfer talent from their Indian GCCs to headquarters. This lets them source top performers from a large pool of solid, cost efficient tech talent. What does the $100,000 fee do to this?

There’s no way to know for sure. But as a recent Times of India article argues, the $100,000 fee might just accelerate this boom. If it costs six figures to bring a talented engineer from Bengaluru to Seattle, might it make better sense to hire more engineers in Bengaluru and move all the work there instead? Unlike Indian IT, there are no contracts on the line. An inability to export people doesn’t put contracts at risk. To them, it’s purely a cost proposition. And if it becomes much harder to bring workers to the US, the economics might just favour a new India office.

The irony is palpable: policies aimed at protecting American jobs might end up pushing more high-value work out of the US.

The New Reality

Maybe the new H-1B rules may not make much of a difference to the survival of the Indian IT industry.

It does, however, point to a darker geo-economic direction the United States wants to take — one where it tries clamping down on services exports to the US altogether. At the same time as this clamp-down, the United States is also debating the HIRE Act, which, if implemented, will put a 25% duty on US companies that outsource jobs in tech. The US is, in a sense, trying to reverse the process of globalisation, keeping as much business as it can within its borders.

Can it succeed? We’re not sure. But it can do plenty of damage even if it fails.

That said, every crisis presents a hidden opportunity, and for all we know, this might be one for us. Indian IT knows, it seems, is already prepared for any eventuality — including changing its business model. Meanwhile, the government is already taking steps to ensure further support for our GCC ecosystem. The H-1B's new price tag may have priced out the Indian dream of reaching America, but it might just bring America's work to India instead.

France's Debt Crisis: A nation at crossroads

Another prime minister has fallen in France. Less than a fortnight ago, François Bayrou became the country's second prime minister to resign in less than a year.

This wouldn’t be so worrying if what we were seeing was just a political drama. But the world’s seventh-largest economy is caught in a cycle of utter misery. Its unending political paralysis is holding it back from pursuing much needed reform, fuelling ever-greater levels of economic deterioration, which make its political problems even worse.

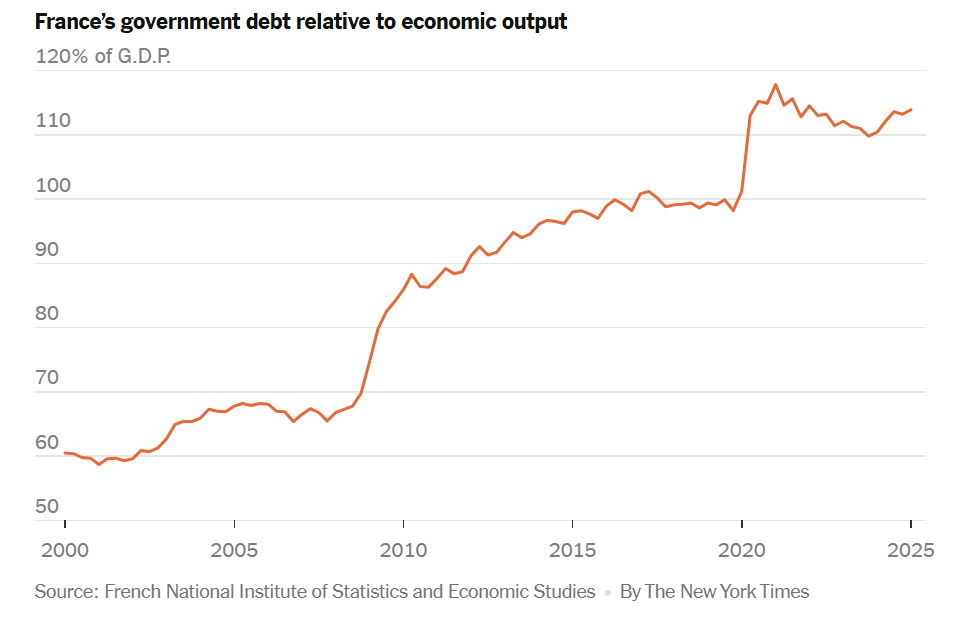

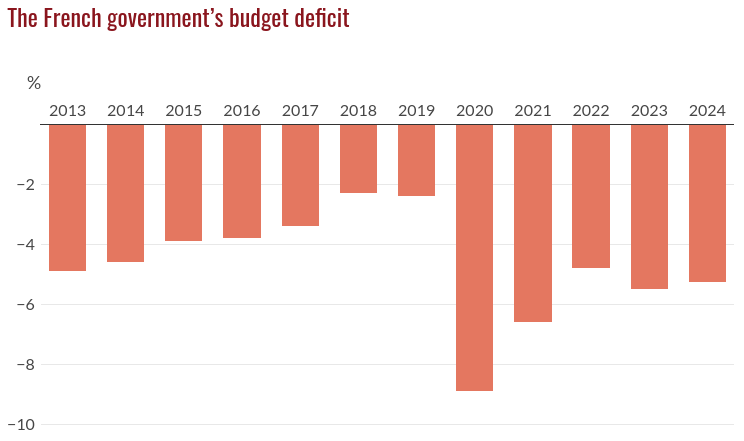

This deadlock cannot carry on indefinitely. The country is already spending well beyond its means. Its fiscal deficit touched 5.8% last year — almost double Europe’s prescribed 3% limit — while its overall public debt is accelerating rapidly, slated to reach 116% of GDP this year.

Investors haven’t taken kindly to this. The crisis has become so bad that France's biggest corporations are now considered safer bets than the French government itself, with the bonds of companies like L'Oréal, Airbus, and Axa trading at lower yields than French sovereign debt. Fitch recently downgraded its credit rating from AA- to A+.

This is the story of how France, one of the biggest industrial powerhouses of the modern era, found itself in a moment of reckoning. Let’s dive in.

Spending without earning: France’s impossible dilemma

The problems of today’s France, arguably, lie in a “social contract” it formed in a very different era: in the glorious decades that followed the Second World War. This was a period of profound change. After losing many decades to sub-par growth between two horrible wars, France’s economy finally took off, growing at over 5% a year for nearly three decades.

Within a single generation, the country urbanised, modernised, and became almost universally affluent.

This created a society where workers gained immense power. And as they gained a political voice, they set out on a grand mission to create a more just society. Those choices secured an exceptional standard of living for the French people. It also, however, locked the country on a path of unsustainably high public spending, combined with a sharp loss in economic competitiveness.

French solidarity

France evolved a social model called l'État-providence, or “the provider state”. The state, it was believed, had a duty to protect all citizens against the primary risks of life: sickness, old age, family-related costs, and unemployment.

It began in the late 1960s. Until then, the country’s focus had been on setting up massive, state-owned “national champions” across sectors — often run at the expense of workers. By the end of the 1960s, however, French workers embarked on a series of massive, nation-wide protests that the state didn’t like. Over the 1970s, it enacted an ambitious set of worker-centric labour reforms, which included: a high minimum wage, extensive unemployment insurance, restrictions on firing, and more.

But, by the 1980s, France was beginning to stagnate. The limits of its state-led economy were becoming clear; the government could create industry, but surviving an increasingly global marketplace was beyond its ability. They had run into a dilemma — with workers becoming all-powerful, they couldn’t risk reforms that would hurt them. But they had little choice; the country had to privatise its industry, even though it could have meant political suicide.

And so, they struck a compromise that scholars have called “social anaesthesia”. Even as it closed down factories and deregulated markets, the government floated a series of policies — like massive pensions and income guarantees that would pacify the worst-hit. More bargains were struck over the years; by the 2000s, the French government promised people everything from universal health coverage to 35-hour work weeks.

This was, arguably, a success. France liberalised with relatively little social upheaval. Over time, these choices secured an exceptionally good quality of life for the French people — who enjoy a lot of leisure time, along with exceptionally low levels of inequality. This ambitious program, however, came with major trade-offs.

The trade-offs

France’s “social anaesthesia” era set expectations for how the government was to act — de-risk people from shocks of all kinds, or the people would protest. And that has proved to be a hard compromise to keep alive.

For one, this has locked France into a cycle of endless spending. France spends 57.2% of GDP through government channels — one of the highest rates of spending in the entire world. The money for this comes from exceptionally high taxes. That includes sky-high payroll taxes; for every €100 that a French employer pays out, only ~€53 actually reaches the worker. This makes French workers exceptionally expensive — and prices them out of most competitive markets.

Its policies also sucked away the vitality of French industry, pushing the French economy into a state of deindustrialisation. In 1975, for instance, France’s manufacturing sector made up ~19% of its economy. Today, that has nearly halved to 10.3%, with 2.2 million industrial jobs lost in the process. Germany, in comparison, has maintained its manufacturing base at roughly a quarter of its GDP.

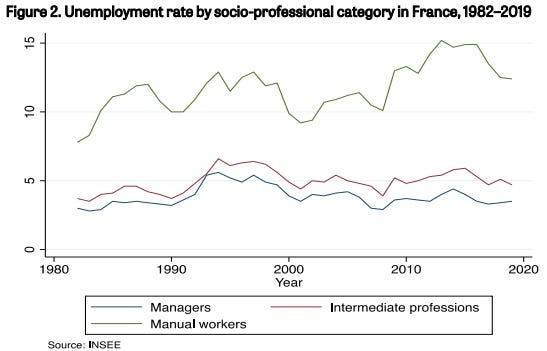

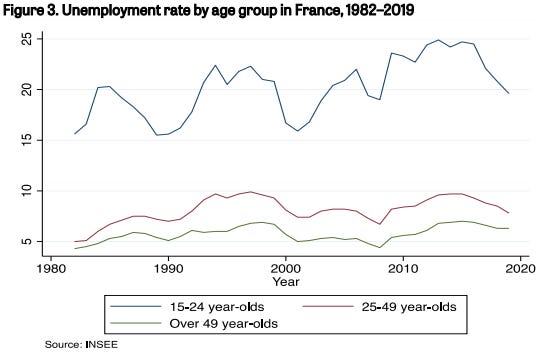

France’s extensive labour protections have also made it exceptionally hard for regular people to land a job. While they clearly benefit those with relatively stable, well-paying jobs, for those on the fringes of France’s labour force, they’re a barrier to employment — like those working menial jobs….

… or young people just entering the workforce:

The French labour force is now in a dual market — much like in India, many French workers are only hired for temporary or contract roles, and find it incredibly hard to land permanent jobs.

And that is the irony of France’s current situation: despite heavy social spending, an increasing number of French workers — especially blue collar workers — are in deep distress, feeling left out of the French economy.

The public debt keeps rising

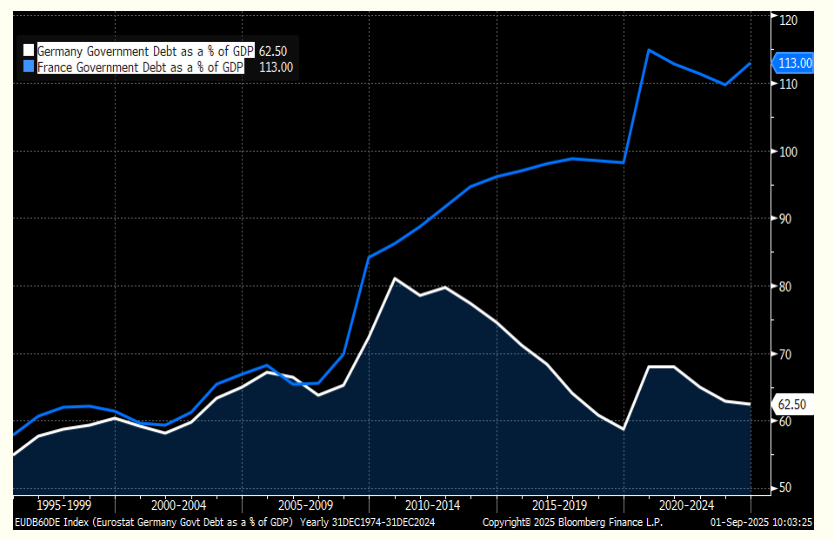

Until the 2000s, France’s model seemed sustainable. In a world that was experiencing incredible economic growth, combined with low interest rates, its level of spending seemed sustainable — and even desirable. Before 2008, France's debt stood at a manageable 60% of GDP — below most of Europe, and about the same as the eternally-conservative Germany.

The global financial crisis of 2008 marked a turning point. When the contagion first spread from America to Europe, most of Europe was caught in a prolonged economic nightmare. But the choices each country made over that time sealed their fate in the years to come.

France kept spending its way through much of the “Eurozone crisis”. Its public spending, as a share of GDP, regularly exceeded the rest of Europe by as much as 7-10%. Most of this was fuelled by debt, and the country’s public deficits crossed the 3% European limit almost every single year. This expansion of debt set an unsustainable baseline for the country.

Despite this spending, however, by 2017-18, it still felt like the French economy was refusing to take off. Unemployment was chronically high, investment was sluggish, and its GDP growth had fallen behind its OECD peers. And so, President Macron introduced a package of pro-business economic reforms. These were broadly targeted at two things: one, easing labour laws and boosting hiring, and two, reducing taxes.

Politically, these reforms were tough to sell. The French working class had just seen a decade of economic malaise and deindustrialisation, and this seemed like an unacceptable pro-rich turn. People took to the streets, in what were called the “yellow vest” protests.

Fiscally, too, it was a gamble. All these tax cuts would, at least in the short term, add to France’s public debt problem.

Perhaps the government hoped that both problems would eventually take care of themselves. The reforms, they believed, would eventually bring more investment and growth. The jobs it created would calm public anger, and the taxes it generated could solve the public debt problem.

But fate — rather, CoVID-19 — had other ideas.

When the pandemic rolled around, the French government publicly committed to do “whatever it takes” to counteract its impact. The French public was already angry, and more hardship was politically unacceptable. And so, the government committed to even high public spending, even as its economy was being crushed. In 2020, the country’s deficit touched 9% of GDP — thrice the European limit.

As France spent freely, it opened a massive divergence between the public finances of France and the rest of the EU. In 2020 alone, France’s debt load went up by ~17%, to 114.6%. Suddenly, France’s debt was well over its annual GDP, and has remained there ever since. The rest of the Euro area, meanwhile, has maintained a more manageable debt-to-GDP ratio of ~90%, with Germany at ~60%.

Those problems didn’t end with the pandemic. Back when pandemic-era inflation had sent prices skyrocketing, France used tax cuts and price caps to try to keep energy prices stable, while the state paid for the short-fall. But even as the disease subsided, those energy bills simply kept climbing. The Russia-Ukraine war cut off Europe’s access to cheap Russian energy, and France’s commitment to stable energy prices became increasingly hard to keep up. In 2 years by the end of 2023, it ended up spending another €100 billion just to cover rising energy costs.

Where France stands

This is where France is stuck.

Its debt burden is exceptionally high, and most of that borrowed money is going into social benefits like pensions. Consider this: 14% of the country’s GDP goes into servicing its pension program. The social contributions France receives for pensions is much less than what it spends on them — creating an annual shortfall of ~€ 70 billion a year. Politically, rolling back that spending is impossible.

Its debt burden, meanwhile, is only increasing. As per government forecasts, interest payments on France's debt are projected to reach €75 billion by 2026 – making debt service the second-largest item in the national budget.

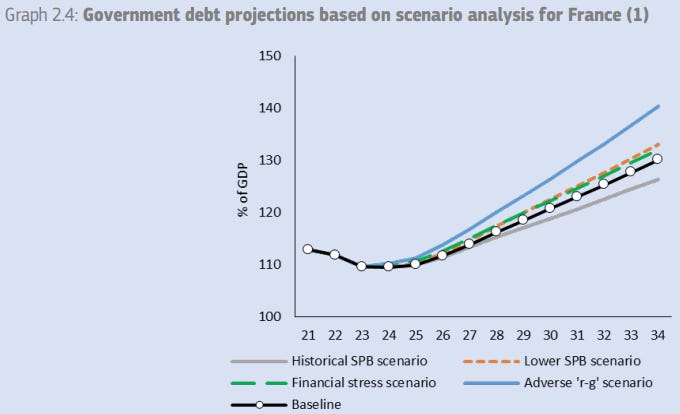

In fact, France has to take on new debt simply to pay back its old debt back while keeping the lights on. As per the European Commission, France’s “Gross Financing Needs” — the amount it will have to borrow each year — will be ~24% of its annual GDP. At that rate, its debt will touch 130% of its GDP by 2034.

In an ideal world, France would grow its way out of its public finance problems. At least in the short term, however, that is unlikely. After a couple of years of middle-of-the-road growth — hovering around ~1% — the country is now seeing a sharp deceleration in GDP growth. The French Central Bank, for instance, expects the country’s GDP growth to slow down to just 0.6% over 2025.

There is, currently, a sense of pessimism across all quarters of the economy.

The French public is holding back on spending. At the same time, with all the uncertainty and weakness we’re seeing in global trade, France’s exports are likely to contract sharply this year — pulling the country’s GDP down by 0.5%. Its world-famous lifestyle businesses — from its wine and spirits makers to its fashion industry — are hurting under the doom-and-gloom across the world economy. And in the face of these many problems, its private sector isn’t confident enough to invest into its economy either.

There is no economic engine, it appears, that’s rushing in to save France.

The political storm

And that brings us to the ouster of François Bayrou. Because, on top of its profound economic challenge, France faces a political challenge which makes it difficult to break out of this situation.

It began in 2022, when President Emmanuel Macron, after winning the Presidency, immediately lost his parliamentary majority. His centrist coalition was forced to govern without a clear mandate, relying on opposition support. The limits of this arrangement became clear the very next year. With deficits running out of control, Macron tried to raise the retirement age from 62 to 64 — and the country erupted in another round of strikes and protests.

Macron's government was forced to push the reforms through without a parliamentary vote, but that only eroded his political capital, deepening public anger. By 2024, things had deteriorated dramatically, with the far-right National Rally (RN) — once considered a fringe political outfit — emerging on top at the European Parliament elections.

This is when Macron made a high-stakes gamble, dissolving the National Assembly and calling snap elections. It backfired. The country elected a hung parliament, split between three blocs that refuse to see eye-to-eye —- the left-wing New Popular Front alliance, the centrist Ensemble coalition, and Marine Le Pen's far-right RN. None of them are close to a majority, while their ideological differences make it impossible to work together.

The country has been cycling through prime ministers and struggling to implement reforms. When Prime Minister Michel Barnier proposed austerity measures late last year, his government fell after France’s first successful no-confidence motion since 1962. And while Prime Minister Bayrou survived a series of no-confidence votes earlier this year, he’s now on his way out as well.

An impossible trilemma

France has always prided itself on being different — as a third way between capitalism and state socialism. But now, it’s caught in an impossible trilemma: a steadily worsening fiscal picture, a social contract that passed its expiry date, and deep political paralysis.

The country remains one of the world’s pre-eminent economies, and we don’t expect it to collapse anytime soon. It does, however, face a grinding decade of compromise and decline.

Their predicament, however, is not unique. Countries across the world have made promises over the last few decades that increasingly look impossible to keep today. How France navigates this collision, perhaps, may set the template for everyone else.

Tidbits

KKR has acquired a majority stake in Meitra Hospital in Kozhikode, its third healthcare buy in Kerala after Baby Memorial Hospital. The deal will help expand Meitra’s services, including a new oncology centre, and increase its bed and ICU capacity under KKR’s India healthcare platform.

Yes Bank, backed by Japan’s SMBC which just acquired a 20% stake, is preparing to enter India’s $1 trillion wealth management market to tap the growing ranks of high-net-worth individuals. The bank plans a joint strategy with SMBC over the next three years, while also expanding loans, branches, and services as India’s affluent population surges.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Pranav

So, we're now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what's a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here's the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Have you checked out Points and Figures?

Points and Figures is our new way of cutting through the noise of corporate slideshows. Instead of drowning in 50-page investor decks, we pull out the charts and data points that actually matter—and explain what they really signal about a company’s growth, margins, risks, or future bets.

Think of it as a visual extension of The Chatter. While The Chatter tracks what management says on earnings calls, Points and Figures digs into what companies are showing investors—and soon, even what they quietly bury in annual reports.

We go through every major investor presentation so you don’t have to, surfacing the sharpest takeaways that reveal not just the story a company wants to tell, but the reality behind it.

You can check it out here.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

A good article highlighting risks from changes to H1B visa rules faced by our IT industry and by implication our economy and national security. Govt should do whatever it can to help IT Industry to meet this threat, but the main work here will be done by the industry itself.

Where the government can play decisve role is by putting meat in its talk of 'atam nirbhar' india and encourage IT companies, new or existing, to develop fundamental IT Products e.g. databases like oracle, development tools, compilers, browsers, search engines, office suites, video hosting and all type social and other platforms and encourage indian companies to use these. Over the long run these will Crete millions of IT jobs in india and also allow us to strengthen our security and sovereignty.