The industry that keeps India's lights on

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Down to the wires: inside the wires & cables industry

Did parcel delivery companies deliver this quarter?

Down to the wires: inside the wires & cables industry

One of the most fun things about writing the Daily Brief is that you get to see just how many everyday, banal things you take for granted have entire industries and ecosystems behind them.

One such industry is that of Wires and Cables (W&C).

W&C companies make the wiring that goes everywhere — buildings, electrical lines, trains and metros, electrical goods like fans and mixers, and so on. And we know, that sounds like an uninteresting space. But the industry itself is far from boring. Right now, the industry is churning out cash — with a strong quarter behind it, and more expected ahead. It’s doing so well, in fact, that it has caught the attention of some of India’s biggest conglomerates, who are all planning their own entry into this space.

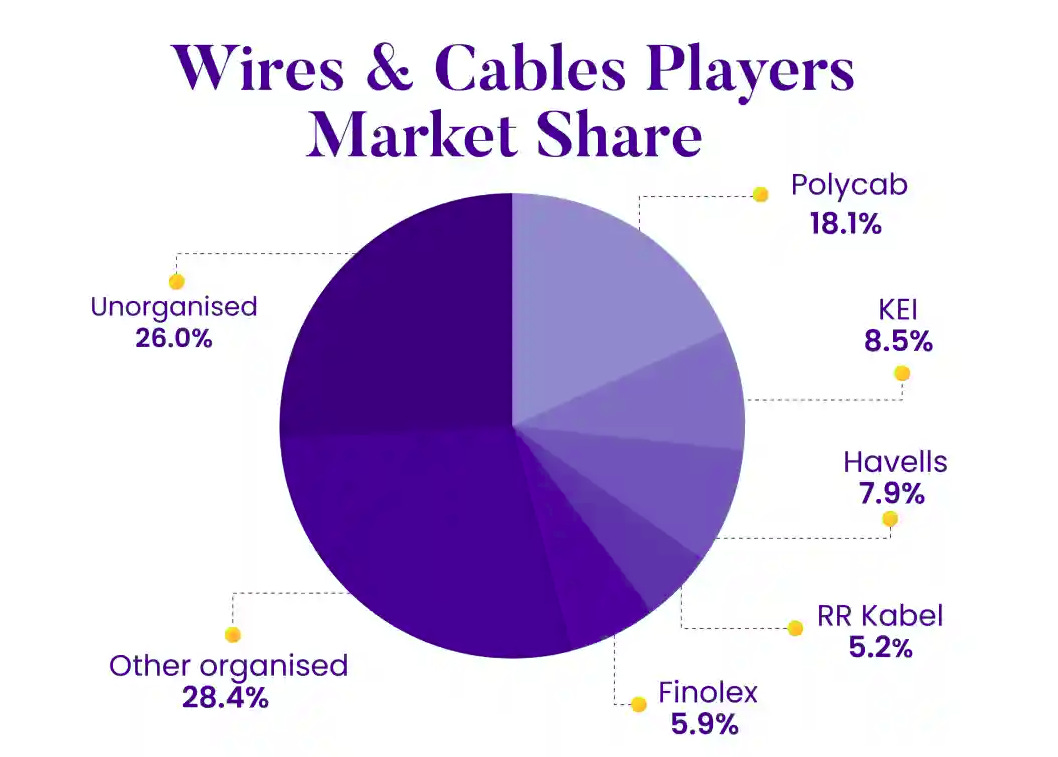

So, what’s happening here? What’s driving this industry’s growth, and why are so many others interested? We’re going to try and understand the industry’s electric quarter through the results of three companies: Polycab, KEI Industries, and RR Kabel.

An electric quarter

For W&C companies, the first quarter of the year is usually the off-season, when revenues dip from the previous quarter. This is because of multiple reasons: governments plan fresh budgets, the rainy weather slows down projects, and dealers run down inventories at the year-end. This year, however, the industry saw a great first quarter

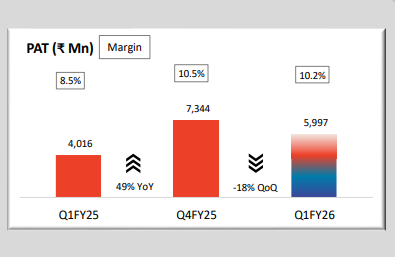

Polycab, India’s biggest listed W&C company, marked its highest-ever first-quarter revenue this year, growing 26% annually to ₹5,906 crore. Its post-tax profits, meanwhile, increased by a whopping 49% to nearly ₹600 crore — pushing its PAT Margin above 10%.

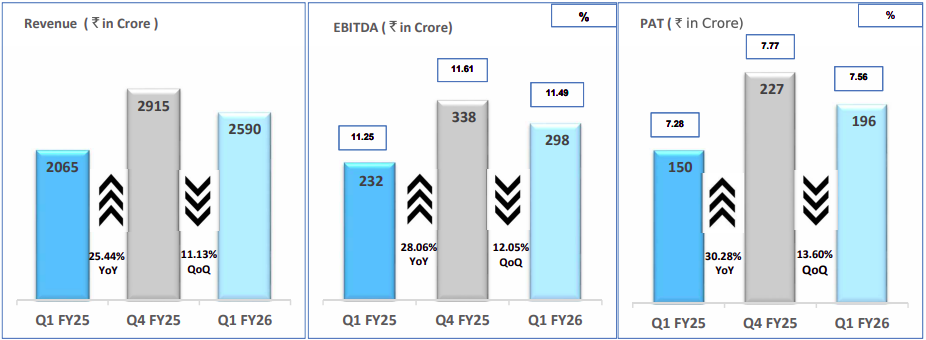

Polycab’s closest (but much smaller) peer, KEI Industries, hasn’t fared too badly either. Its revenue grew by 25.4% from last year to ₹2,590 crore — around the same scale as Polycab. Its net profit also jumped 30%, to nearly ₹196 crore. But at 7.56% of its revenue, its margins are much lower than Polycab in both absolute and relative terms.

Then there’s RR Kabel, the smallest of the three, which was listed just two years ago. This June quarter followed the best quarter in the company’s history, which is why its ₹2,058 crore revenue marked a quarter-on-quarter dip. This was still 13.8% higher than last year, however. Net margins grew by 39.5% from last year to ₹89.7 crore, but only make up 4.5% of the revenue — a much lower ratio than Polycab or KEI.

How to decode these numbers

Where’s all this growth coming from? To decode that, let’s follow the money.

W&C companies usually have three business-lines. One, they make actual wires and cables. Two, they put a few more components together and make ‘Fast-Moving Electrical Goods’ (FMEG) — things like fans, lights, etc. Three, they supply wires to massive Engineering–Procurement-Construction (EPC) projects.

Wires and cables

The heart of their business, though, are wires and cables. And that’s where a lot of their growth came from — Polycab’s W&C division grew 31%; KEI grew 32%; and RR Kabel grew 16%.

Here’s something we didn’t know when we started this piece: wires and cables aren’t the same thing!

Wires are usually single-core — that is, that usually just have one conductor. They’re used for simple, consumer-use applications, like fans or lights.

Cables, though, are multi-core, with many conductors tied together. They’re custom-designed for complex systems like industrial automation or telecom lines — often with very specific requirements in mind. A lot of investment goes into making them, and they have to meet the Bureau of Indian Standards’ (BIS) requirements.

This makes cables harder to make — and deploy — than wires. It also makes wires more profitable than cables. Polycab’s management said as much:

FMEG

Of late, W&C companies have been venturing beyond wiring, to make more complex electrical products — like fans or table lamps. While wires and cables make for a commoditised business, by adding extra value, these companies can push up their margins.

Polycab has the most advanced FMEG business of the three — with 7.5% of last year’s revenue coming from the segment. This partly explains why Polycab’s margins are so much better than its peers. The segment grew by 18% year-on-year in the June quarter.

The company made a deliberate push towards premiumisation, in fact — better looking fans, feature-rich lights etc. — which seem to be what many customers wanted.

In contrast, RR Kabel’s FMEG business — 12-13% of its revenue — has remained flat over the quarter. KEI doesn’t have a FMEG line yet.

EPC

Customers rarely know which company they want wires from. And so, if you’re trying to reach regular consumers, dealer networks are everything. If you have wide dealer networks, and good relationships with them, you’re likely to make more money. Good networks can also win you higher margins.

In contrast, W&C companies also make large B2B sales for giant EPC projects. These can bring you huge volumes. That said, these are very competitive, and tenders usually go to the lowest bidder — pushing margins down.

That’s probably why it isn’t anyone’s focus — averaging less than 6% of the revenue of W&C players. Polycab and KEI, in fact, are deprioritizing EPC in favor of the other two divisions because of its low margins.

Where companies spend

That’s what these companies sell. But what do they spend on making wires and cables?

Well, raw material — copper and aluminium — is the largest expense for these companies by far, making up over 70% of their costs.

Both are commodities, and their prices can fluctuate considerably. And it isn’t always possible to pass those costs on to buyers. Imagine, for instance, that you’re a W&C company that’s bought a lot of copper supplies — only for prices to fall unexpectedly. Your costs are high. But others might be willing to offer your dealers better prices, and they might expect you to do the same. You might have no choice but to stomach lower margins.

This isn’t an imaginary situation, by the way — it happened with Finolex last year.

This is even harder if you’ve signed a lot of EPC contracts. There, your prices are fixed irrespective of future increases in costs, and a bad patch of volatility can make a project unprofitable.

Unstoppable growth

While this may have been a good quarter for the W&C industry, this isn’t the only one by far. The industry has grown at an impressive 19% annually from FY19 to FY24, and future projections look promising too.

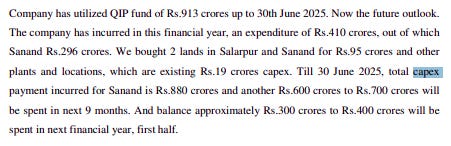

These companies certainly believe in the industry’s growth prospects, and they’re willing to funnel serious amounts of money to back that belief. Polycab, for instance, plans to spend ₹6000-8000 crores on new capacity over the next 5 years. KEI has already spent ₹880 crores on a new plant in Gujarat and plans to spend at least ₹600 crores more.

Why are they so confident? What’s driving the industry’s incredible growth? There are two reasons that stood out to us.

Real estate boom

Indian real estate is booming, growing over 3.5x in the last five years, reaching nearly 1 billion square feet of space. And they’re only expected to grow further.

All of those buildings need extensive electrical wiring. Here’s what another wiring major, Havells’ India said:

Government spending

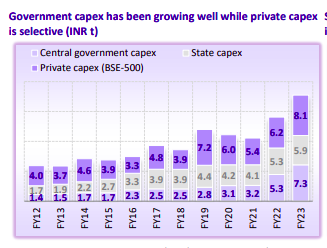

A lot of money is also coming from government spending, however.

Some of it is direct, from infrastructure projects. The government has put serious sums of money into all sorts of projects — railways, utilities, defense, housing, and so on — and its spending is only growing. The wiring for all these projects comes from private W&C companies.

More importantly, however, a lot of that spending reaches these companies indirectly. Consider its Production-Linked Incentives (PLIs), meant to boost manufacturing in India. Not only do those incentives help manufacturers; when they set up or expand factories, they also spend heavily on wiring and cabling. The same is true for other projects that crowd in investment.

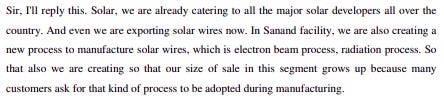

The rise of renewable energy, in particular, is very interesting for this space. The government is currently funding massive solar and wind projects — which need huge amounts of specialised cabling that few players can make.

Companies like Polycab and KEI have jumped in early to the opportunity, and have been making incredible gains. KEI, for instance, is doubling down on solar projects:

Can they survive the Goliaths?

The industry’s bright long-term prospects have not gone unnoticed. Some of India’s biggest conglomerates now want in on the fortunes it promises. Which is why, earlier this year, both the Adani and Aditya Birla groups announced their entry into the space.

Both conglomerates have arms that can feed the segment, and that need the segment.

Both are involved in many downstream businesses, which need wires and cables. For example, Adani has massive investments in power transmission, solar projects, real estate and infrastructure. Such projects are often driven by government tenders, and having an in-house W&C division could help them cut costs and bid lower.

Both conglomerates also have massive cement arms — and most projects that require cement also require wires and cables. Those businesses, and their supply chains, could complement this expansion.

At the other end, both Adani (in Kutch Copper) and Birla (with Hindalco) own some of the largest copper miners in India. That allows them to supply cheap copper to a W&C arm, and ensure that supplies are a lot more predictable.

There are no structural hurdles that can keep them out either.

The W&C industry is still fragmented, with a quarter of all business captured by unorganized, non-branded players. There’s space for new entrants to make a splash. Basic wires aren’t too hard to make, requiring little machinery and capex. Nor do you need to spend years creating a trusted brand — as long as dealers and electricians endorse you, you can get your product out there.

When the two conglomerates announced their entry into the space, the stock markets were rattled. Polycab, for instance, fell almost 20% in late February after UltraTech’s announcement.

KEI, similarly, fell 14% on the day of Adani’s announcement, the next month.

Were the markets over-reacting, though? Or are these companies in genuine danger?

From what we can tell, the incumbents aren’t sitting silently, nor are they too nervous about new competition.

They’re doubling down; strengthening their already-robust distribution network and brand. They still have advantages — including the loyalty and networks they’ve built over time. The new entrants may have experience with government projects, but they don’t have an inherent advantage in the high margin retail segment. Finances alone don’t give Adani or Birla a right to win.

Cables, specifically, also follow strict BIS certification standards — and approvals can take a long time. The more complex a project, in fact, the harder it is to get approval for your cables. The incumbents all have lots of experience and patience, here, and new entrants could take time getting there.

In fact, incumbents believe it will take at least 3-4 years for them to set up production and distribution.

Meanwhile, the incumbents aren’t sitting still. They’re moving into new product lines rapidly, while deprioritizing those with low margins. Take UV-resistant solar cables, for example — very few companies have the expertise to make such cables, allowing the incumbents to draw a large premium. It is in such products that the battle between the two may be fought.

The entry of Adani and Birla might put some of the unorganized players out of business. But the battle with organized incumbents will be far harder. And more exciting, too.

Did parcel delivery companies deliver this quarter?

Delhivery and Blue Dart have both announced their Q1 FY26 results, and we figured we haven’t talked much about such businesses in our newsletter. Logistics is a fairly simple sector — companies help you move things from one place to another. Everyone needs it — from your favourite e-commerce site getting your brand-new phone to your doorstep, to companies sending spare parts to their dealers.

And it doesn’t just include the transportation of these goods through either road, railway, or air. It’s much more than that. It includes warehousing, where goods are stored before being shipped. Or sorting—figuring out which parcels go where. Sometimes even reverse logistics—for example, returning goods if they’re broken, or recycling.

So we thought: let’s break down how these two companies performed this quarter. But more importantly, these results revealed to us how differently they go about doing the same thing. Even though they both move parcels, their playbooks couldn’t be more different.

Let’s start with some numbers

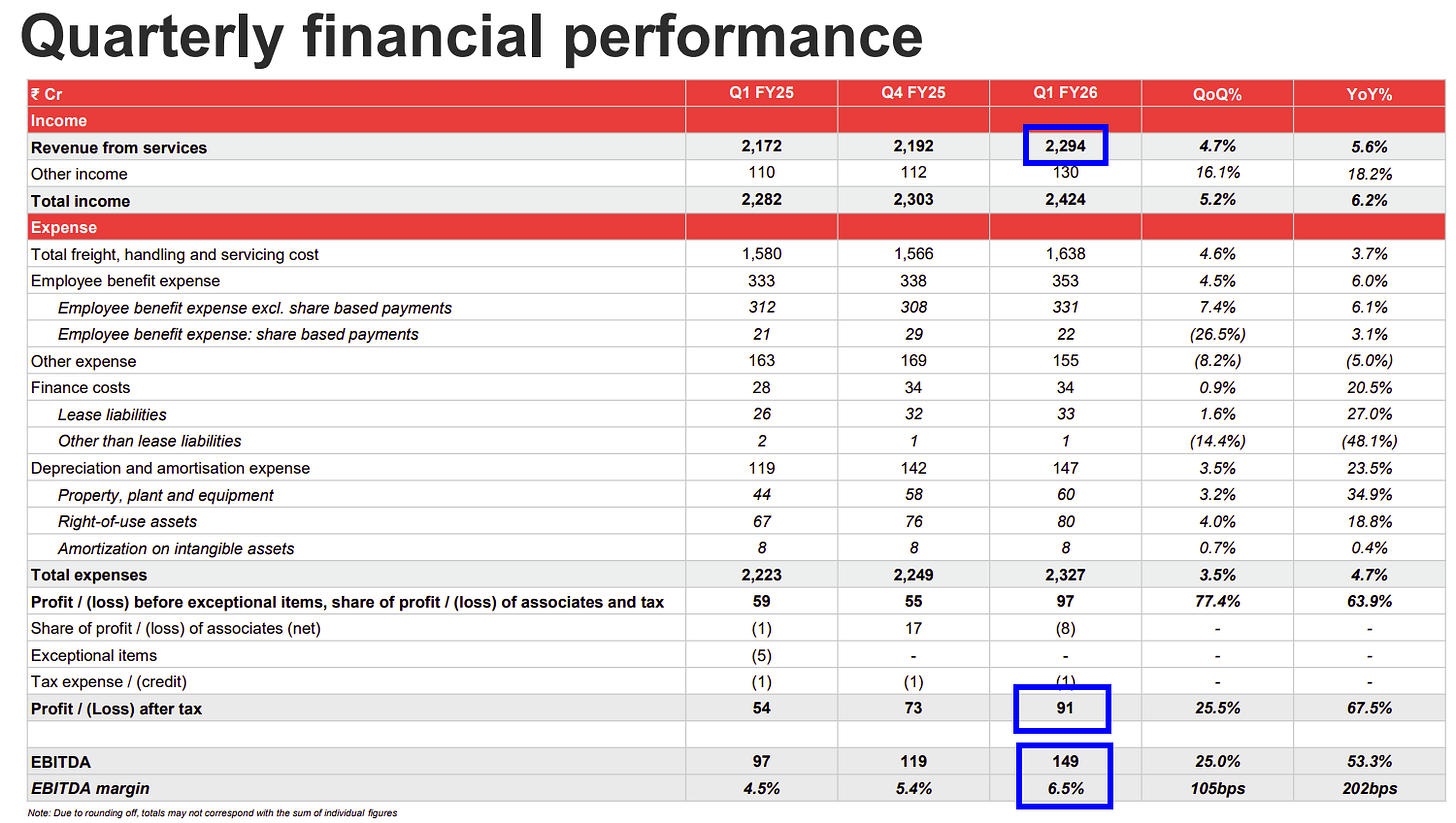

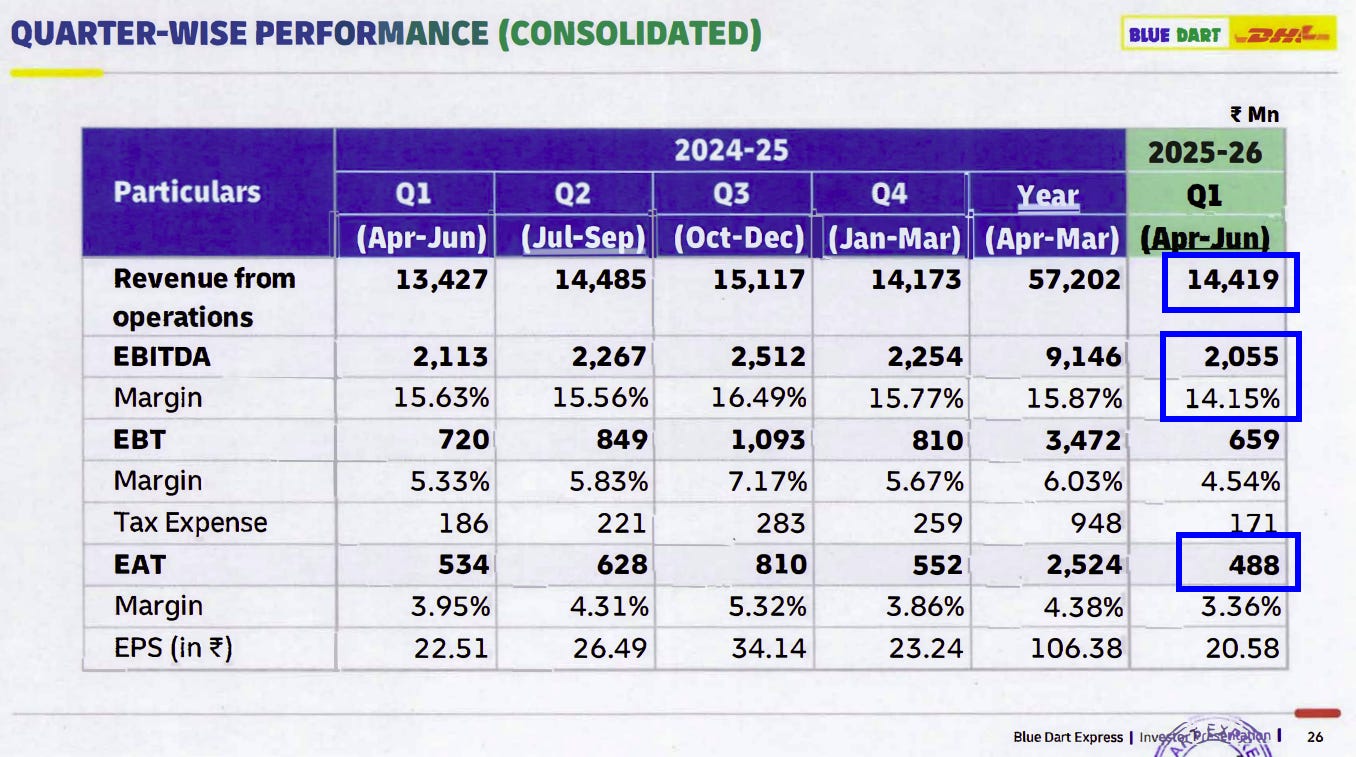

Delhivery’s revenue for the quarter was about ₹2,294 crore, significantly higher than Blue Dart’s ₹1,442 crore. Yet, Blue Dart clings to its edge in profitability – it managed an EBITDA margin of 14.5% versus Delhivery’s 6.5%.

In relative terms, Blue Dart’s margins beat Delhivery. But in absolute terms, the new-age upstart Delhivery actually earned almost double the net profit of the old guard Blue Dart this quarter (₹91 crore vs ₹48 crore). We’ll eventually get to why that is. But in essence, Delhivery is playing a volume game (even at the expense of margins), while Blue Dart is squeezing more value out of each rupee.

This is a recurring theme that echoes throughout their differences in way of approaching business. Here are three of those that stood out to us

First, B2B or B2C

The first divergence lies in the customer type that each company serves.

So far, Blue Dart has built its name on serving businesses (B2B) and high-value customers. B2B has historically made up over 70% of their business — corporate packages and critical documents are their bread and butter. Delhivery, though, made its mark hauling millions of online shopping orders to regular consumers (B2C).

However, Q1 FY26 saw a flip in this equation. Most of Blue Dart’s growth this quarter actually came from B2C e-commerce parcels: its revenue from consumer shipments surged 20.2%, while revenue from its traditional B2B clients barely grew 2.4%. The share of B2C in Blue Dart’s increased from 26% last quarter to 29% in Q1 FY26. But relying on B2C is a double-edged sword for Blue Dart: those consumer shipments bring in volume but at thinner margins than its typical corporate express deliveries.

Delhivery, for its part, has e-commerce in its DNA — after all, they began as a hyperlocal food delivery service. Where it’s now branching out is B2B and freight. After acquiring a freight company called Spoton a couple of years ago, Delhivery has been aggressively growing the B2B segment.

We’re essentially watching a role reversal in slow motion. Delhivery, born in B2C e-commerce, doesn’t just deliver your fashion parcel from Myntra; it also wants to handle a manufacturer’s 200 kg pallet shipment to a distributor. Blue Dart, conversely, seems to be reiterating the reverse: while quality B2B service is its turf, it can no longer ignore the e-commerce flood.

However, even within the e-commerce boom, both are playing their hand very differently.

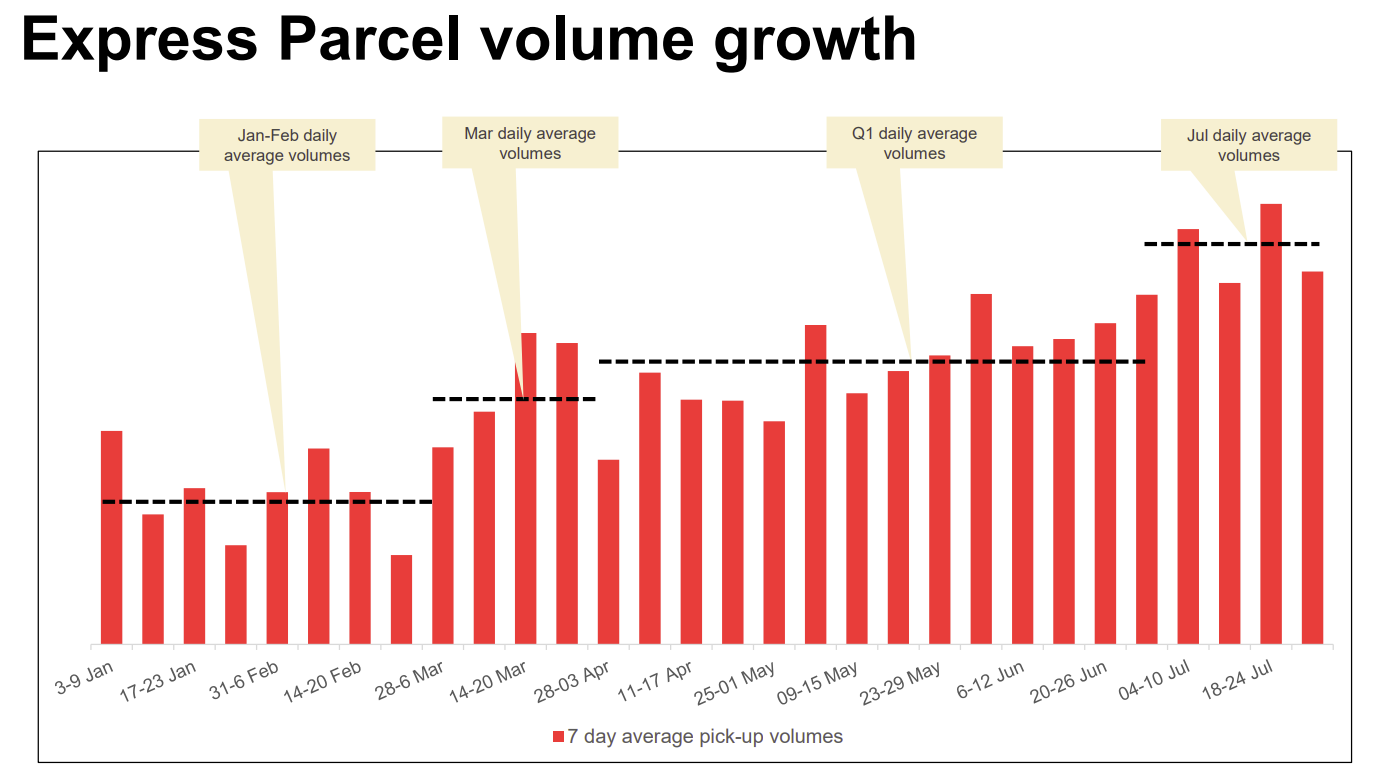

E-commerce is a huge driver of growth in the express delivery business for these companies, expected to grow~25% CAGR till 2030 as per a RedSeer estimate. Express delivery is the delivery of parcels weighing less than 40 kilograms with a typical delivery time of 3-4 business days.

Delhivery is doubling down on e-commerce. In fact, it just acquired rival Ecom Express, a major e-commerce delivery firm, in a ₹1,407 crore deal this April. This move beefs up Delhivery’s volume — its parcel volumes jumped 14% from last year to 21 crore shipments in the first quarter of FY26 — and extends its reach among online sellers.

Delhivery is even venturing into the latest trend in town: quick commerce. In Q1, it invested about ₹14 crore to launch a 2-hour delivery service (“Rapid Commerce”) and an on-demand intra-city delivery service. They want to work with quick commerce platforms and help offer them high precision appointment based deliveries between dark stores and mother warehouses.

CEO Sahil Barua noted that while this foray is just 100 days old, it’s already an “exciting growth driver” for their part-truckload business.

Blue Dart, on the other hand, hasn’t jumped into hyperlocal 10-minute deliveries at all – its focus is firmly on its core strengths, like express deliveries. Blue Dart’s management has even signaled a renewed focus on B2B shipments as a “broader opportunity” beyond e-commerce. Essentially, Blue Dart would rather use their profits to further invest in doing what they already do best.

Second, How They Deliver

The difference between Delhivery and Blue Dart isn’t just in who they serve, what they charge or how they position themselves. It’s also in how their delivery networks are built, and that affects their business economics.

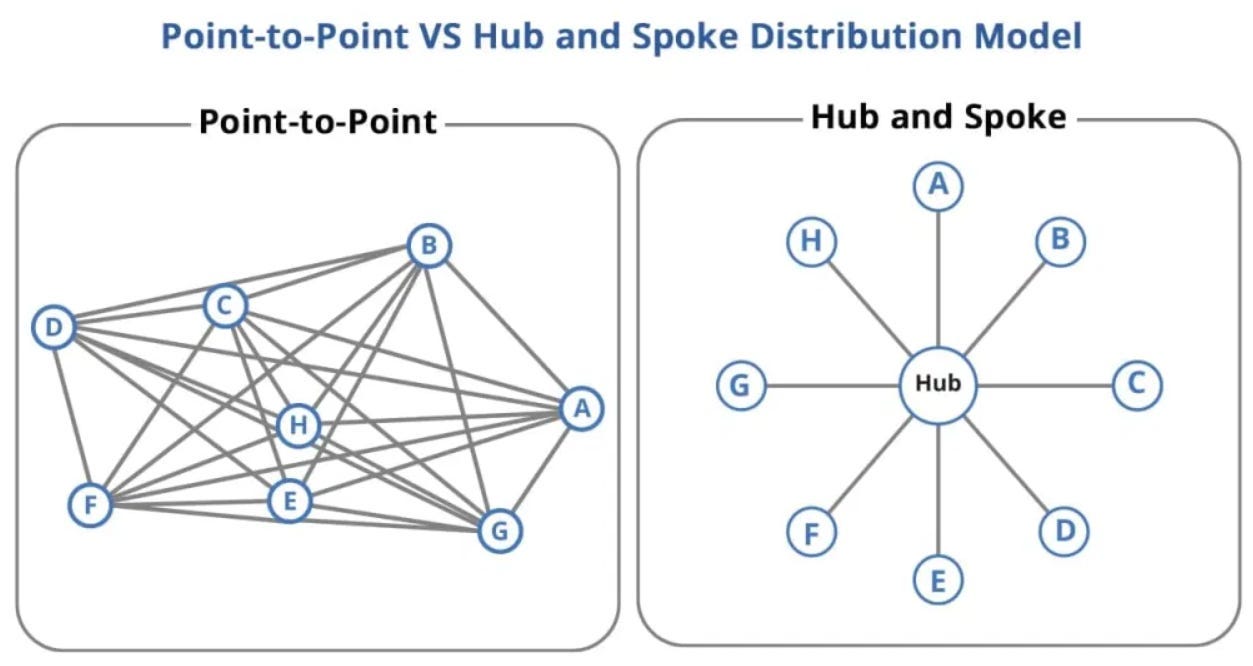

Blue Dart primarily follows a hub-and-spoke model. Think of it like a wheel—parcels from smaller locations are first collected and sent to big central hubs, sorted there, and then sent out again toward their destination. This system gives them tight control and is suited for scheduled, high-value deliveries. Adding an extra spoke for one hub is also much less expensive.

But it also requires huge upfront investment in your own physical infrastructure, massive sorting centres, and your own airline fleet — all of which Blue Dart has. So when volumes drop, profits can take a hit. But when volumes rise, profits do very well.

Delhivery, on the other hand, runs a point-to-point network. There’s no single “hub” that everything flows through — each point is connected to others and parcels move directly between connected nodes. It’s more dynamic and lets Delhivery optimize routes on the fly. This reduced their fixed costs, giving them a more flexible, variable cost structure. They can easily ramp up or down based on demand, without being stuck with large, idle facilities or expensive aircraft leases. This gives them the benefit of higher volumes.

However, this also means that they don’t enjoy heavy economies of scale like Blue Dart does. With scale, connecting all points with each other can be a far more complicated and expensive task that requires a lot of technology and analytics (something Delhivery has lots of expertise in). Moreover, each point has to maintain its own inventory, unlike the hub-and-spoke model where only the hub needs to manage that.

Blue Dart has higher operating leverage, while Delhivery has better downside protection. Both models have merit—but they’re clearly playing very different games.

Third, Brand Positioning

Blue Dart markets itself as the premium express logistics provider, whereas Delhivery is all about being the accessible, mass-market logistics platform. This philosophy shows up in their operations.

Blue Dart, for example, runs its own airline fleet – six Boeing 757 freighters flying India every night, giving it the ability to guarantee overnight deliveries. It even offers niche services like “Domestic Priority 1030”, which promises delivery by 10:30 AM the next day for urgent shipments. Its couriers are famously professional (uniformed, ID cards and all) and it has a 42-year legacy of trust to uphold. All of this is why companies and people pay a hefty premium to ship via Blue Dart.

Delhivery takes a different route – it focuses on reach and efficiency over luxury. Delhivery doesn’t own planes; instead, it relies on a vast ground network and partners. It serves 18,700+ pin codes across India, using tech-driven routing to handle high package volumes at low cost. Blue Dart might ensure your parcel arrives in perfect condition at a guaranteed time, but Delhivery’s promise is to cover everywhere at an affordable price.

For example, shipping a small 500g package with Blue Dart can cost 2-4 times more than sending the same parcel via Delhivery. Blue Dart’s customers willingly pay that premium for reliability and speed, akin to buying a first-class ticket for their parcel, while Delhivery’s customers prioritize cost savings and accept that service might be a bit more economy-class.

Blue Dart is the trusted Mercedes of the logistics world, and Delhivery is the WagonR that’s ready to go anywhere. Neither approach is “better” universally; they cater to different customer priorities. And that premium positioning is also why Blue Dart’s EBITDA margins are double those of Delhivery.

Conclusion: Miles Apart in Strategy

In the end, although both Delhivery and Blue Dart are in the same sport of moving packages, the games they’re playing couldn’t be more different.

One runs an air fleet; the other runs on sheer ground network scale. One courts price-sensitive online sellers and buyers; the other courts time-sensitive corporates and high-value clients. The only thing they truly have in common is that they deliver parcels from point A to point B. Everything else – the how, the whom, and the why of their business – couldn’t be more different.

And that makes watching their quarterly results all the more interesting: it’s not just about who wins, but how they’re running.

Tidbits

India is planning new measures to boost the economy as the US prepares to slap steep tariffs on exports. The government wants to cut red tape, support local manufacturing, and keep growth steady despite global pressure.

According to Reuters sources, India's tax authorities are investigating whether Jane Street violated tax laws by booking profits via its Singapore entities on its derivative trades in the Indian market. Searches at the U.S. trading firm's India offices by the income tax department have been underway since last week.

SEBI wants mutual funds, ULIPs, and pension funds to get a bigger share in IPOs. It's planning to raise their quota and cut retail allotment to boost long-term investor participation.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Kashish

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

I like how you have written everyday banal things have entire industries. Interesting read.

This is good work I love reading this whenever I am at work traveling great source of knowledge keep it up you guys