The Hidden Barriers Keeping Poor Nations Poor

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The Poverty Trap: Why Nations Can’t Escape

$1 Trillion in FDI? The Story of India’s Growth

The Poverty Trap: Why Nations Can’t Escape

Let’s start today with something that’s both important and worrying. It’s an issue that affects millions of people and, in turn, the future of our world.

A recent report from the World Bank has revealed a troubling trend: the poorest countries in the world are struggling to climb the economic ladder. In simple terms, they’re stuck while others continue to move ahead.

But what does this really mean, and why should we care?

Let’s break it down.

Countries around the world are grouped based on income levels—basically, how much the average person earns in a year. The poorest of these are called low-income countries. People living in these places often survive on less than $3 a day. That’s just enough to cover the basics like food and shelter.

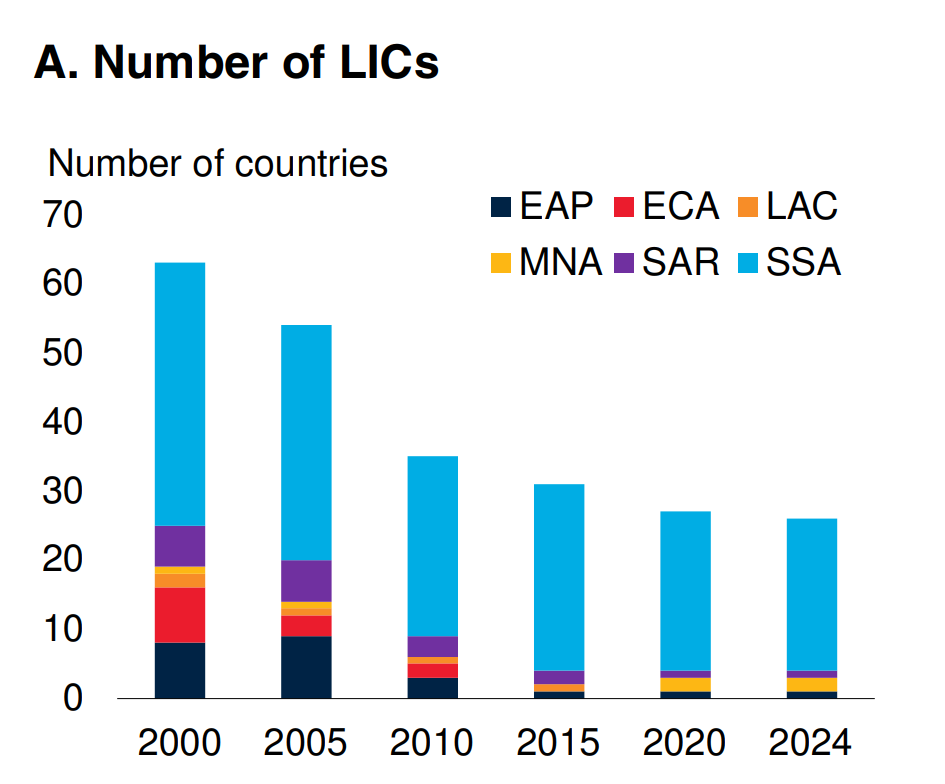

Countries like Ethiopia, Madagascar, Yemen, Afghanistan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo are examples of low-income nations. Right now, there are 26 countries in the world still in this category.

To give you a sense of how tough that is, think about this: a cup of coffee at Starbucks often costs more than what people in these countries have to live on for an entire day.

To understand what’s happening, we need to look back at the early 2000s. Back then, something hopeful was happening. Many poor countries were breaking out of poverty at an incredible pace.

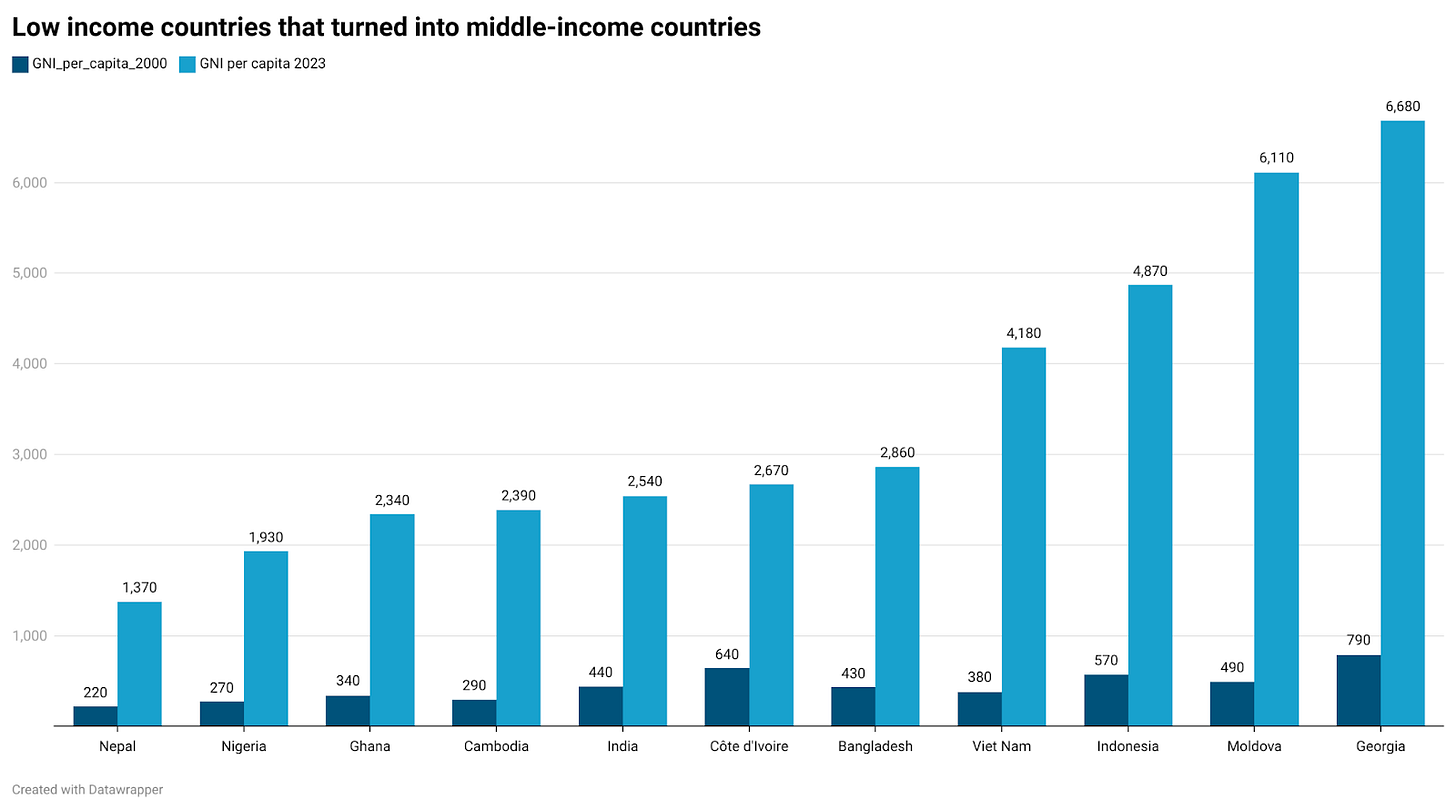

Between 2000 and 2010, dozens of nations managed to transform their economies, moving from low-income to middle-income status.

Let’s look at a few examples:

India went from being a struggling economy to becoming the fifth-largest in the world.

Bangladesh, once almost synonymous with poverty, transformed into a key manufacturing hub.

And Vietnam, despite enduring years of war, became one of Asia’s fastest-growing economies.

Back then, it felt like the world had figured out a formula for progress. Out of 63 low-income countries in 2000, 39 managed to move up to middle-income status. It was seen as proof that even the poorest nations could rise with the right support, policies, and circumstances.

But here’s the worrying part: that momentum has slowed down significantly.

Today, 26 countries remain stuck as low-income nations. What’s even more concerning is that only six of them are expected to make it to middle-income status by 2050. Just six out of 26.

Let’s look at some numbers to understand the situation in these countries better:

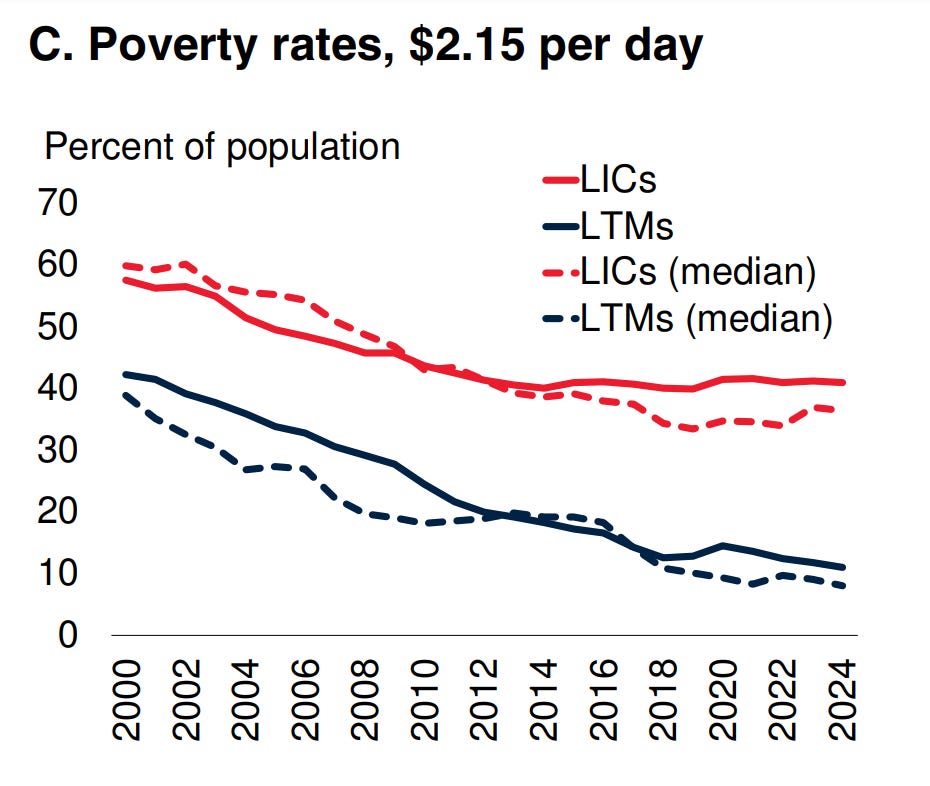

Four out of ten people live on less than $2.15 a day—that’s barely enough to survive.

Only about one-third of the population has access to electricity. Many people live without lights, fans, or even the internet.

For every 10,000 people, there’s just one doctor. That’s a dangerously low number.

And the reasons behind this are not tied to just one issue—it’s a mix of many challenges coming together.

Conflict and Fragility

Two-thirds of these low-income nations are stuck in fragile or war-torn situations. Wars destroy infrastructure, disrupt education, and force millions to flee their homes. Over the past 20 years, deaths from conflict in these countries have been 20 times higher than in other developing nations.

Take South Sudan, for example. Without ongoing conflicts, its GDP per person could be three times higher. Think about the countless opportunities lost because of war.

Lack of Infrastructure

Every economy needs basics like roads, power plants, schools, and hospitals to grow. On average, people in low-income countries have access to just one-fifth of the infrastructure available in countries that recently moved to middle-income status.

For perspective, when India was a low-income country in 2000, it already had better infrastructure than most low-income countries today. That gave it a head start.

Climate Change

These countries are being hit hardest by climate change. A drought or flood in a wealthy country like the U.S. might slightly lower economic growth. But in low-income nations, a single drought can slash growth by 1%—three times as much.

The problem? These nations don’t have the resources to recover or adapt.

Debt Burden

More than half of these countries are buried in debt. Many spend more on paying back loans than on healthcare. Imagine having to choose between repaying creditors and saving lives.

Source: World Bank Declining International Aid

And here’s the twist: just when these countries need the most help, global support is shrinking. Official development aid has dropped to its lowest level in 20 years.Right now, these nations receive about the same amount of aid per person as middle-income countries did back in 2000—despite facing much bigger challenges.

But despite these challenges, there’s also hope. These countries have untapped resources and opportunities that could completely change their futures. Let’s look at a few examples:

Natural Resources

Take the Democratic Republic of Congo. It holds more than 50% of the world’s cobalt reserves—a mineral that’s critical for making electric vehicle batteries. Many of these nations also have large reserves of graphite and other minerals essential for green energy. If managed well, these resources could become the backbone of their economies.Solar Energy

Most of these countries are located in what’s known as the “solar belt,” the region with the highest solar energy potential on Earth. With proper investment, they could use solar power to build industries and process their minerals locally, creating jobs and driving growth.Tourism

Rwanda shows what’s possible with tourism. By making mountain gorillas a premium attraction, the country has turned tourism into a major part of its economy. Other nations could follow this example by leveraging their unique landscapes and wildlife.Young Population

While much of the world is aging, these countries have a very young population. About 40% of their people are under 15. This could be a huge advantage—more workers, more energy, and more innovation—if they are given access to education and opportunities.

Now, let’s step back and see the big picture. Over 40% of the world’s extreme poor live in these countries. If these nations succeed, global poverty could drop significantly.

What’s more, their mineral resources are essential for the world’s green transition. Without their success, efforts to fight climate change could face serious delays.

To meet basic development goals, these countries need massive investments—about 8% of their GDP every year. That’s a big number, but the potential rewards are even bigger.

This isn’t just about lifting millions out of poverty. It’s about unlocking opportunities that could benefit the entire world. With the right policies, investments, and support, these countries have the potential to become the economic powerhouses of the future.

$1 Trillion in FDI? The Story of India’s Growth

India recently crossed an incredible milestone in foreign direct investment (FDI). Since April 2000, the country has attracted a total of $1 trillion in FDI. At first glance, this sounds like a huge achievement. A trillion dollars flowing in to support or establish businesses in India seems like a big win for the economy.

But what does this number really mean? Where is the money coming from? Where is it going? And most importantly, is it enough to meet the needs of a growing economy like India’s?

To understand this better, let’s take a step back and look at how foreign investments in India have evolved over time.

Before independence in 1947, foreign investments were heavily focused on industries like tea, railways, and mining. These investments were designed to serve colonial interests, benefiting the British far more than India.

After independence, India adopted socialist policies, including strict limits on foreign ownership. By the 1970s, foreign companies could only own up to 40% equity in Indian businesses. This discouraged global players, leading companies like IBM and Coca-Cola to leave the Indian market.

Things changed dramatically in 1991. India faced a serious balance of payments crisis—the country was running out of money to pay for imports. This forced the government to open up the economy to foreign investments. For the first time, 100% foreign ownership was allowed in certain sectors, and global companies started paying attention.

Over the years, sectors like automobiles, telecom, and consumer goods attracted significant foreign interest. The momentum picked up even more after 2000. Starting in 2014, under the Modi government, FDI rules were further relaxed. Campaigns like “Make in India” and “Digital India” also helped draw global investments.

What’s even more impressive is that about 70% of India’s total FDI inflows since 2000 have come after 2014.

So far, this might sound like a success story. More money coming into the country should be good news, right? Well, not entirely. The headline figure of $1 trillion doesn’t tell the full story. While gross inflows have grown, the money flowing out of the country has also increased. This means the net FDI—the amount that actually stays in India—isn’t as impressive as it seems.

There’s another perspective to consider. When we compare FDI to the size of India’s economy, the numbers aren’t as flattering. Today, FDI makes up just 1.1% of India’s nominal GDP, one of the lowest ratios in the past decade. As India’s economy grows, it’s not attracting enough foreign investment to keep up with that growth. While this isn’t necessarily a cause for alarm, it’s something worth keeping an eye on.

Another issue is where this investment is going within India. Geographically, it’s highly concentrated. Just three states—Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Gujarat—together attract about 70% of all FDI inflows. That leaves the rest of the country with just 30%, creating an uneven distribution of benefits.

On the positive side, the sectoral distribution of FDI is more balanced. Investments are spread across industries like services, software, trading, telecom, and manufacturing, which is a good sign for diverse growth.

Now, let’s talk about where this money is coming from. Globally, the biggest sources of FDI include the United States, the Netherlands, and China. But in India’s case, two countries dominate: Mauritius and Singapore. Together, they account for nearly half of all FDI inflows into India.

This might seem surprising at first. Mauritius and Singapore don’t have massive economies themselves. Mauritius, in particular, is known as a tax haven, often used as a channel for investments originating from other countries. Singapore, however, has shown genuine interest in India’s potential, with its sovereign wealth funds playing a major role.

China, on the other hand, ranks far lower than expected. Globally, it’s the third-largest source of FDI, but in India, it’s only 22nd, contributing just 0.37% of India’s total FDI equity inflows.

Why is China’s contribution so low? The answer lies in trust and geopolitics. India and China have a complicated relationship. While they are major trading partners, they’ve also faced tensions and conflicts.

In 2020, after clashes at the border, India became more cautious about Chinese investments. The government introduced “Press Note 3,” a rule requiring approval for any investment coming from countries that share a land border with India. This rule effectively slowed down Chinese FDI. India also started scrutinizing Chinese companies more closely, banning hundreds of Chinese apps and keeping a watchful eye on sectors like 5G and consumer electronics.

This cautious approach is rooted in security concerns. No country wants foreign investors it doesn’t fully trust to control critical parts of its economy. However, this approach may need some rethinking. Other countries, like Vietnam and South Korea, have found ways to balance their relationships with China. They’ve benefited from Chinese investments while diversifying their supply chains and reducing over-dependence on China. By allowing Chinese capital into specific industries, they’ve boosted their exports and integrated more deeply into global supply chains.

For India, this presents both a challenge and an opportunity. If India wants to become a global manufacturing powerhouse and fully leverage the “China+1” strategy—where companies reduce dependence on China by investing in other countries—it might need to reconsider its stance on Chinese FDI.

Right now, India relies heavily on Chinese imports but doesn’t add much value to these products before exporting them again. Allowing more Chinese investment, especially in areas like renewable energy, semiconductors, and heavy engineering, could help India build its own capabilities and reduce its trade deficit.

Chinese funding could also complement India’s Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes, which aim to boost domestic manufacturing. With access to advanced Chinese technology and expertise, India’s local industries could grow significantly. That said, this doesn’t mean opening the doors wide. India would need to carefully regulate which sectors are open to Chinese investment and ensure that sensitive industries remain protected.

In conclusion, India’s $1 trillion FDI milestone is a major achievement, but it’s only part of a larger story. While the numbers are impressive, there are important challenges to address—from the uneven distribution of investments within the country to geopolitical complexities with key players like China.

If India can navigate these challenges wisely, it has the potential to attract even more investment and strengthen its position in the global economy. Striking the right balance between security and growth will be key, especially as the world works to diversify supply chains and reduce reliance on any one country. With the right policies, India can turn FDI into a powerful engine for achieving its economic ambitions.

Tidbits

Bharti Airtel has prepaid ₹3,626 crore to the Department of Telecommunications (DoT), clearing all its dues from the 2016 spectrum auction. This adds to the ₹28,320 crore the company has already prepaid in 2024. That includes ₹7,904 crore for the 2012 and 2015 spectrum auctions (paid in June) and ₹8,465 crore for 2016 dues (paid in September).

Bangladesh’s interim government has accused Adani Power of breaking a 2017 energy deal by not passing on tax benefits from India. The deal, which was signed without a tender, has faced criticism for being much more expensive than Bangladesh’s other coal power agreements. Since power supply began in July 2023, Bangladesh has struggled to pay its bills, with pending dues running into hundreds of millions of dollars. While some of Adani’s payments remain overdue, Bangladesh now claims it has enough domestic capacity to manage without Adani’s power—though not all its power plants are currently operational.

Accenture secured $1.2 billion in generative AI orders last quarter, bringing its total bookings to $4.2 billion since September 2023. This single-quarter figure is almost equal to LTIMindtree’s entire annual revenue, showing just how disruptive AI is becoming in the IT sector. Even with flat IT budgets, businesses are reallocating funds to generative AI, highlighting its growing importance in their strategies.

-This edition of the newsletter was written by Bhuvan and Kashish

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉 Join the discussion on today’s edition here.

There's only one reason why countries that are poor remain poor: lack of morality in society. No morality --> little widespread trust --> corruption --> weak institutions --> no development. It takes serious social reform in order to civilise the heathens and make a country develop.