The govt wants to make housing affordable for all

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

Check out the audio here:

Spotify:

Apple Podcasts:

And the video is here:

In today’s episode, we look at 3 big stories:

The govt wants to make housing affordable for all

China is getting rid of its oil addiction

Today's youth is stressed and anxious

The govt wants to make housing affordable for all

Let’s talk about how the government is trying to make housing more affordable for everyone.

In India, owning a home is a big deal. It’s not just a place to live; for many, it’s the most important asset they own. In fact, over half of all household wealth in India is tied up in property. And it’s not just an Indian thing—governments all over the world push for homeownership because it gives people a sense of financial stability. But India has a huge housing shortage, with some estimates saying we’re short by 5 to 10 crore homes. Plus, not many people here take out home loans compared to other countries.

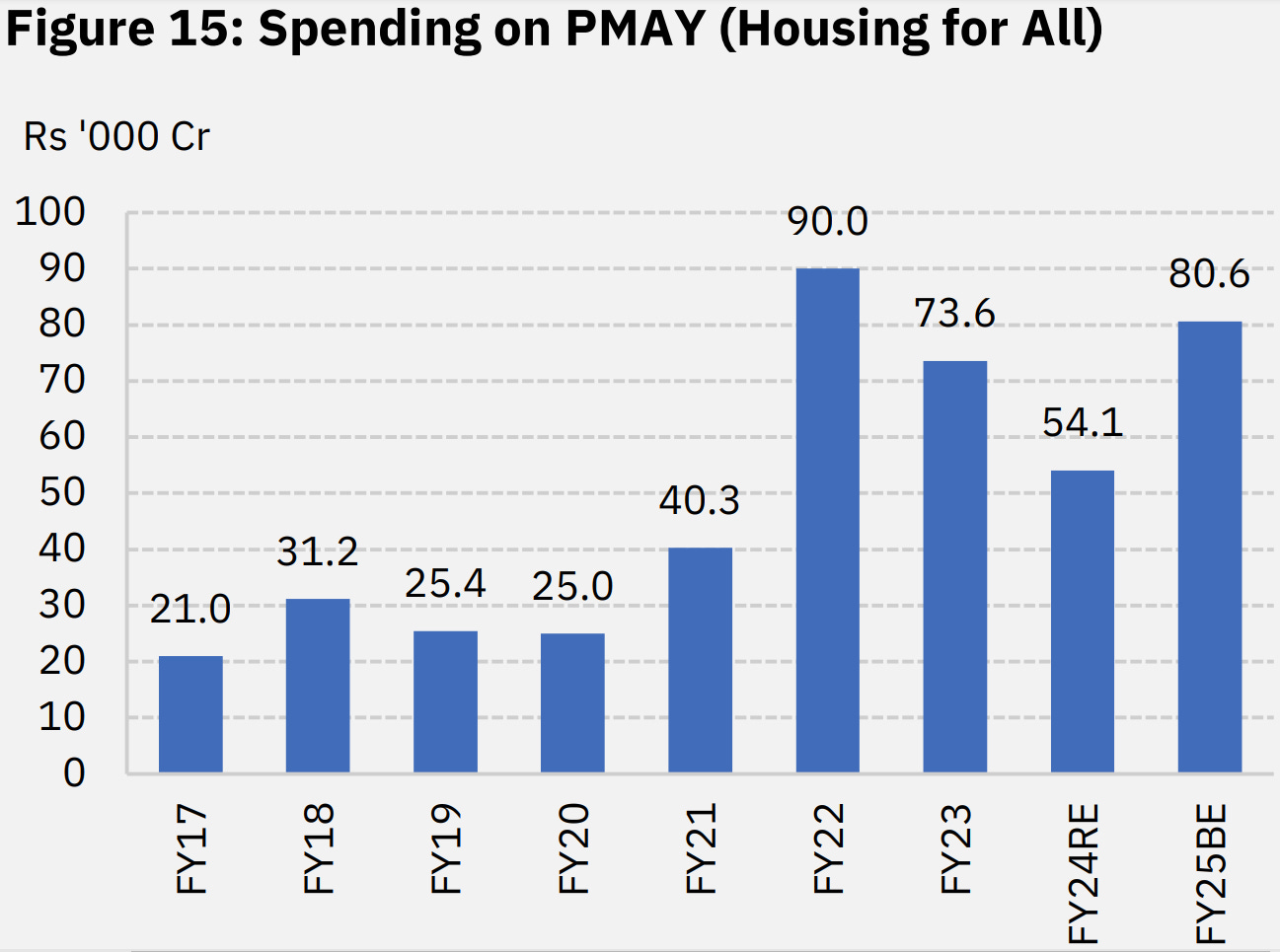

Back in 2015, the Indian government launched the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) to tackle this issue. The goal? To make housing affordable for the poorer sections of society through things like subsidies, financial help, and encouraging the construction of affordable homes, whether by the government or private companies.

The scheme has two parts: one for urban areas and one for rural areas. By June 2024, around 80% of the houses targeted under the urban scheme were built, while the rural part hit most of its goals. Sure, there have been some complaints about the quality of the houses or whether the right people got them, but we’ll dive into that in another episode.

The first version of the scheme was supposed to wrap up in 2022, but it got extended to 2024. In the recent budget, the government rolled out a new version to build 3 crore more homes in urban and rural areas. The cabinet just approved the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana-Urban, so here’s what you need to know:

Over the next five years, the government plans to help 1 crore urban poor and middle-class families either rent, build, or buy a home at an affordable price. They’ve set aside ₹10 lakh crores for this. To make sure banks and housing finance companies don’t get burned by defaults, the Credit Risk Guarantee Fund has been boosted from ₹1,000 crore to ₹3,000 crore.

The government is also offering incentives to developers to build affordable homes, and for buyers, they’re providing interest subsidies.

But here’s the catch: the new scheme isn’t as generous as the old one. They’ve capped or reduced the maximum subsidy, the interest subsidy, the loan amount, and the property value.

Even though the new scheme is a bit more restrictive, Jeffries research suggests it still covers about 60–70% of the loans given under the old scheme. For the housing market, this is good news, especially for housing finance companies that focus on affordable housing.

China is getting rid of its oil addiction

Let’s dive into something intriguing happening in the oil markets—China seems to be kicking its oil habit. Last week, OPEC made a slight adjustment to their global oil demand forecast for 2024, trimming it down to 2.1 million barrels a day. And guess what? A big part of this drop is due to falling demand in China.

If the global economy slows even further, we might see oil prices dropping even more. But there's more to the story—while OPEC is trying hard to keep prices up by cutting production, non-OPEC countries like the U.S., Canada, Guyana, and Brazil are ramping up their oil output. This creates a fascinating push and pull in the market right now.

To give you some context, even though OPEC+ agreed to a production cut amounting to about 5% of global demand, their forecast remains pretty optimistic compared to others. The Energy Information Administration and the International Energy Agency are predicting a demand increase of only about one million barrels a day.

Now, let’s zoom in on China. Something’s definitely going on with their economy, and it’s showing up in their oil imports:

China’s growth has been sluggish lately, and the outlook doesn’t seem much brighter. The ongoing property crisis is dragging on, and household spending is still weak. To keep things steady, China’s trying to export as much as possible, but other countries are starting to push back with tariffs.

China seems to be transitioning to LNG-powered trucks, which is cutting down their diesel demand.

Here’s a surprising stat—half of all vehicles sold in China in July were either pure electric vehicles or hybrids. Just three years ago, that number was a mere 7%.

Looking ahead to 2025, oil forecasts are a mixed bag, leaning slightly positive. But everything hinges on how the global economy shapes up and whether geopolitical tensions flare up. There’s a lot more going on in the oil world, and we’ll be digging into those details in upcoming episodes.

Today's youth is stressed and anxious

Let’s talk about something that’s been a hot topic lately—global youth unemployment. The International Labor Organization (ILO) just released a new report on Global Employment Trends for Youth 2024, and it has some pretty eye-opening findings. Now, we’ve covered jobs quite a bit on the podcast, mainly because the job market, not just in India but globally, is in a tough spot.

The report is a hefty 116 pages, so I’ll boil it down to nine key points that really stood out.

In 2023, the unemployment rate for young people worldwide was 13%. That might sound high, but believe it or not, it’s the lowest it’s been in 15 years. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it spiked to 15.6%. But here’s the thing—this number only reflects those who are actively looking for work. About 20.4% of young people aren’t just unemployed—they’re not even in school or getting any kind of training. So, the picture is a bit bleaker than the numbers suggest.

The ILO predicts that the global youth unemployment rate will dip slightly to 12.8% by 2025. But in regions like the Arab States and parts of Asia, unemployment rates are expected to remain stubbornly high.

In high-income countries, 76% of young adults have secure jobs. But there’s a growing trend towards temporary and unstable work. The rise of gig work and short-term positions is creating a lot of anxiety among the youth, and for good reason. This generation has seen the fallout from the 2008 financial crisis and lived through the pandemic—economic instability is all they’ve known. In India, gig work has become a new form of informal employment, but it comes with its own set of problems—like no healthcare, insurance, or retirement benefits.

Globally, about 64% of young people are worried about losing their jobs. This fear is even more pronounced in regions like Africa and the Arab States, where over 30% of youth are “extremely” or “very concerned” about job stability.

Here’s a shocking stat—South Asia is missing 45.3 million young women from its workforce. In places like the Arab States and North Africa, young women would need to increase their employment rate by six times just to match that of young men.

In 2023, a lot more young women were out of work and not in school compared to young men. Globally, about 28.1% of young women are in this situation, more than double the rate for young men, which stands at 13.1%.

Nearly half of the global youth population—48%—was in school or training in 2023, up from 38% in 2000. While more education is generally a good thing, it’s leading to a mismatch between the skills young people have and the jobs available, especially in developing countries.

Back in 2001, agriculture was the biggest employer of young people globally. But by 2008, services like retail, hospitality, and food services had taken over. In India, we’ve seen a similar shift. The share of agriculture in total employment fell from 60% in 2010 to 42% in 2019, while construction and services rose. Manufacturing employment, on the other hand, has stayed flat.

Asia still has the highest share of young workers in manufacturing, but this is changing. In China, rising labor costs and a shift away from factory jobs among youth are causing workforce shortages. As a result, manufacturing hubs are moving to regions like Southeast Asia and even parts of Africa.

All in all, today’s youth are facing a lot of stress and uncertainty, and this is before we even consider the potential impact of artificial intelligence and the future of work. The job landscape is changing fast, and it’s clear that this generation is dealing with challenges unlike any before.

Thank you for reading, if you have any feedback do let us know in the comments.