The age of electricity

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The age of electricity

How are roads built in India?

The age of electricity

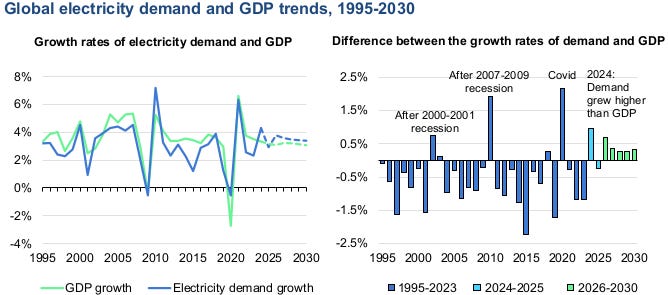

For most of modern history, the world’s hunger for electricity has moved in lockstep with its economic growth. If an economy expanded, its power demand grew roughly in proportion. The relationship was so consistent that it became an unspoken assumption — electricity was a mirror of the broader economy.

That assumption is now broken. According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) latest electricity outlook report, 2024 was the first “normal” year in three decades — that is, the first year without a major global crisis — in which the world’s electricity demand grew significantly faster than its economy. The IEA doesn’t think this was a blip. Through 2030, in fact, it projects electricity consumption to grow at least 2.5 times faster than overall energy demand. Something fundamental has shifted.

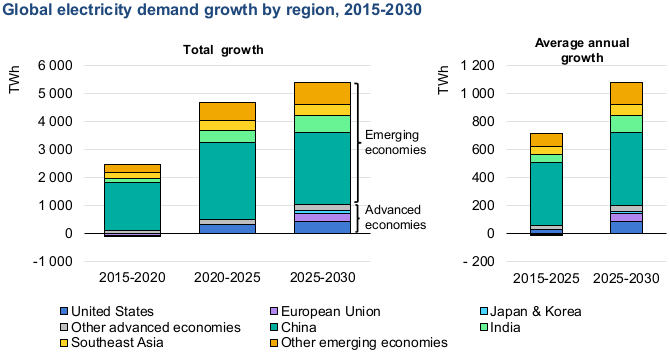

The world, it appears, is entering what the report calls an “Age of Electricity” — a period in which power demand is breaking away from the economy that was supposed to govern it. This de-coupling is already underway. Global electricity demand is expected to grow at an average of 3.6% a year through the end of the decade — almost 50% higher than its ~2.8% growth rate over the previous ten years. In absolute terms, the world will add about 1,100 terawatt-hours (TWh) of new demand every year — roughly half of India’s entire annual electricity consumption, piled on top of existing demand every single year.

We’re living through a phase shift. Understanding why this is happening, what will power it, and what stands in the way tells you a great deal about where the global economy is headed.

Why demand is decoupling

Think of what it means for electricity demand to outpace economic growth. Effectively, every year, every bit of economic activity we carry out is a little more electricity-intensive than a year ago.

This is the outcome of two trends.

The first is electrification — the replacement of other energy sources with electricity. There are things we’re doing that create the same output as before, but we’re turning to electrical power to do it. Activities that once ran on diesel, gas, or coal are increasingly powered by the grid. Transportation is the most visible example of this, with electrical vehicles steadily pushing out their ICE counterparts. We’re making the same switch with industrial processes. This doesn’t necessarily make the economy bigger; but it makes it more electrified.

The second is subtler: we’re using electricity in ways that don’t map neatly to productive output. Air conditioning is the clearest case. As incomes rise and temperatures climb across the developing world, hundreds of millions of people are plugging in cooling systems for the first time. This represents a massive improvement in quality of life, but it doesn’t show up directly in GDP figures: other than as demand for a single product.

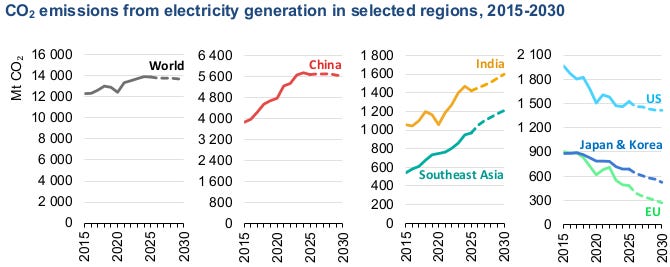

Predictably, over 80% of the world’s new electricity consumption comes from the developing world. China alone accounts for nearly half of this growth — in the next five years alone, it will add demand equal to the European Union’s entire current consumption.

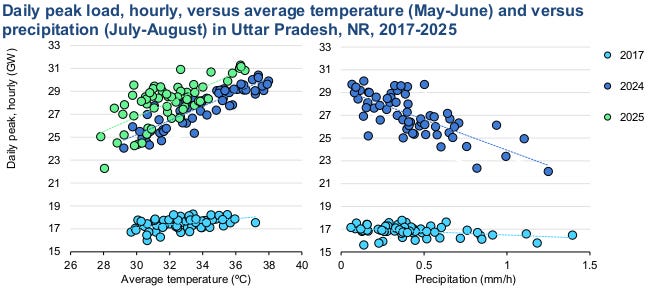

But India and Southeast Asia are growing rapidly too. And as they grow, there’s a visible surge in air-conditioning. Consider Uttar Pradesh. Whenever temperatures rise, you’d naturally expect some uptick in electricity demand as people try to cool down. But the sensitivity of demand to temperature — the surge in power consumed every time temperatures are up by one degree — has increased fivefold since 2017. The use of air conditioners in the state, clearly, has exploded over the last decade.

Interestingly, however, the developing world is no longer alone in driving consumption upward. After roughly fifteen years of stagnation, electricity demand in advanced economies is accelerating as well. The catalyst, here, is computation. AI, data centres, and advanced manufacturing are pulling power demand upward across the United States and Europe. In the US alone, demand is projected to grow nearly 2% annually — with roughly half of that increase coming from data centres.

Where the power comes from

If the world’s electricity consumption is taking off at this rate, the obvious question is: how do we match it with supply?

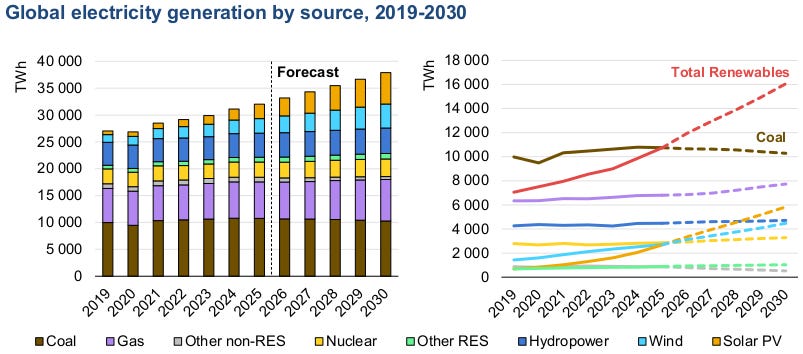

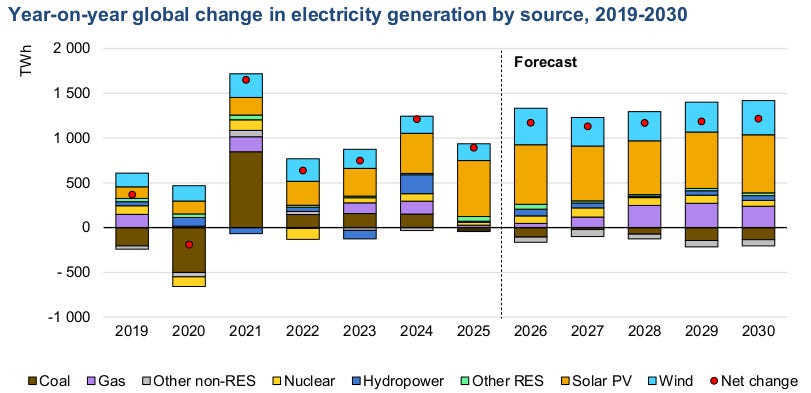

The answer, at least according to the IEA, is surprisingly optimistic. Low-emission sources — renewables and nuclear — are growing fast enough not just to meet all additional global demand, but to chip away at fossil fuels as well. By 2030, these are projected to account for half of all global electricity generation, up from around 42% today. The world is slated to add roughly 1,050 TWh of renewable electricity alone for every remaining year of this decade — which is almost exactly how much new demand it expects to add.

This is powered, in great measure, by a dramatic surge in solar energy. In 2025, the world added 620 TWh of solar electricity in a single year. It’s on track to surpass both wind and nuclear generation by 2026, and hydropower by 2029 — despite being the last of these sources to be deployed at any meaningful scale. In a decade, solar energy has gone from niche to dominant.

There’s also a less appreciated shift in nuclear energy. After years of sluggish growth, nuclear generation has suddenly taken off; and is now projected to expand at 2.8% annually through 2030 — more than double the pace of the preceding five years. As with so many energy trends, the engine here is China. Chinese nuclear generation is expected to grow at 6% per year. And given that the country consumes roughly one-third of the world’s energy, that ramp up is enough to lift the world’s nuclear supply.

On the other side of the ledger, meanwhile, fossil fuels are clearly losing ground. That doesn’t mean they’re irrelevant. Coal will remain the single largest source of electricity globally in 2030. Natural gas, meanwhile, is positioned for an even longer runway: gas-fired electricity generation is set to grow at 2.6% annually. It has become the world’s preferred transitional source, complementing, rather than competing with, the intermittent output of renewables.

In the aggregate, though, we’re turning away from carbon-intensive energy sources. That is a quiet but historic development: because carbon emissions, now, have de-coupled from energy demand.

Despite power demand growing by nearly 4% in 2025, the world’s carbon emissions from electricity production practically didn’t increase at all. For every unit of electricity generated, we’re emitting a little less carbon each year. The IEA projects what it calls a “great plateau” — until 2030, carbon emissions from our power sector will remain flat, even as demand ramps up.

The bottleneck in between

Here’s the upshot of all this: the world is seeing an explosion in its demand for electricity, matched by a historic surge in supply, at least on paper. But there’s a problem. Between the power plants producing electricity and the factories, homes, and data centres consuming it, there’s a vast, creaking network of transmission and distribution infrastructure.

And this is turning out to be a terrible choke-point.

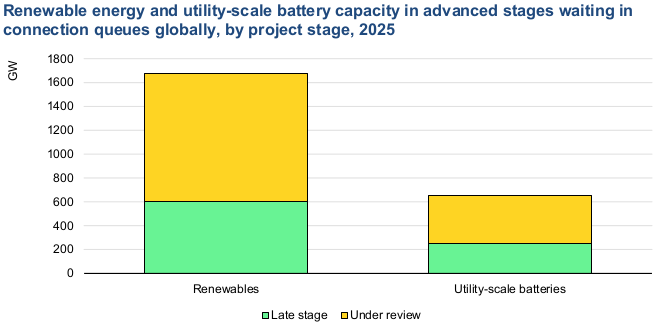

The world’s power grids were not built for the energy system now taking shape. There is currently a backlog of over 2,500 gigawatts of projects — renewable generators, battery storage systems, data centres, and more — that are simply stuck in grid connection queues, waiting to be plugged in. Among these, 1,700 GW of completed renewable projects sit in advanced stages of approval. Another 600 GW of batteries are lined up behind them. And 150 GW of data centres are waiting for connections — putting roughly a fifth of the world’s planned data centre build-out at risk of delay.

This is a self-reinforcing problem. Because getting a connection is so uncertain and slow, many developers submit speculative requests for projects that may never materialise, clogging the queue further. The IEA estimates that only about one in five data centres currently seeking a grid connection will actually be built. But every speculative application takes up space in a line that real projects also need to join.

This all hangs on a simple problem: grids take ages to build; far longer than anything else in the energy system. Planning and constructing new transmission infrastructure takes anywhere from five to fifteen years. Renewable power plants, by contrast, take one to five years. Data centres take one to three. The grid, in other words, is the slowest-moving piece in a system where everything else is accelerating. To meet projected 2030 demand, annual investment in grid infrastructure would need to rise by roughly 50% from current levels.

What options do we then have, if it isn’t feasible to build power lines?

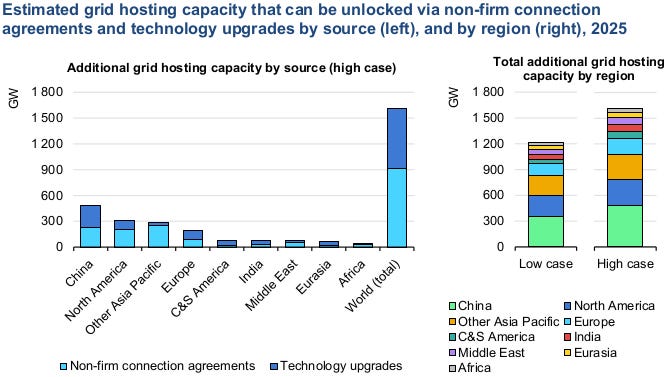

The IEA thinks 1,200 to 1,600 GW of projects currently stuck in queues can be unlocked without major new transmission lines. Part of the answer lies in regulatory innovation. Some countries have introduced ideas like “non-firm” connection agreements, where projects can connect to the grid on the condition that they’ll be cut off if the load exceeds what the system can handle. This kind of flexible arrangement could free up around 900 GW of capacity globally.

Another answer lies in what the industry calls “grid-enhancing technologies” — upgrades to existing infrastructure that help it carry more power without being rebuilt from scratch. These alone could unlock a further 900 GW.

That said, our grid challenge isn’t just about moving enough electricity through. As we transition to renewables, we’re coming upon a new class of engineering problems.

Fossil fuel plants are controllable. You can ramp them up and down to match demand in real time. Renewables, by their nature, are not. Solar output, for instance, surges at midday and vanishes at sunset. As these variable sources grow, the grid has to absorb far larger swings in supply — and it has to do so without losing stability.

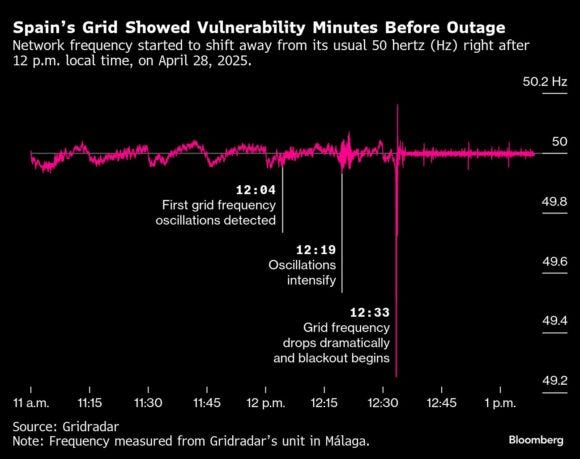

That doesn’t happen automatically, and the cost of a failure can be catastrophic. In April 2025, for instance, the entire electrical grid serving Spain and Portugal collapsed. There were severe oscillations in supply which overwhelmed the region’s grid infrastructure, and within half an hour, the entire system went dark. It took more than twelve hours to restore power.

Failures like this become much more likely as the share of variable renewables grows.

This new generation of problems can be solved. Our current build-out of battery storage, for instance, is an engineering response to a key problem with renewables. This transition will need a suite of new engineering solutions — from better forecasting to smarter demand management to grid architectures that can absorb volatility without breaking.

What it all means

In all, the IEA’s report is a sketch of a world caught in an inflection point — in the middle of a generational boom in both energy demand and supply. We’re setting up new energy infrastructure at a blistering pace, while at the very same time, we’re creating the most energy hungry technology we’ve ever seen. The world is moving faster than most people imagine.

But a shift this big is never easy. Between supply and demand sits the grid — an ageing, slow-to-build infrastructure layer that was designed for a different era. The coming decade will be shaped less by whether we can generate enough clean electricity, and more by whether we can move it to where it’s needed, when it’s needed, without the whole system coming apart.

The age of electricity has arrived. The infrastructure to support it has not.

How are roads built in india?

We recently saw a headline that forced us to stop mid-scroll: NHAI Accepts RIIT’s Rs 9,500 Cr Offer To Monetise Five Highway Sections. We could tell it was about road assets and “monetising” them… but that’s pretty much where our understanding ended.

So we did what any self-respecting geek would do, and went digging. There was a lot of ground we had to first cover to understand that single sentence: how does India build roads? Where does the money come from? Who’s responsible for what? And crucially: how do people make money in this whole chain?

If you’ve read even a little about this, treat this as a quick revision. If you’re like us and had no clue how this world works, consider this a 101 primer.

Meet the cast

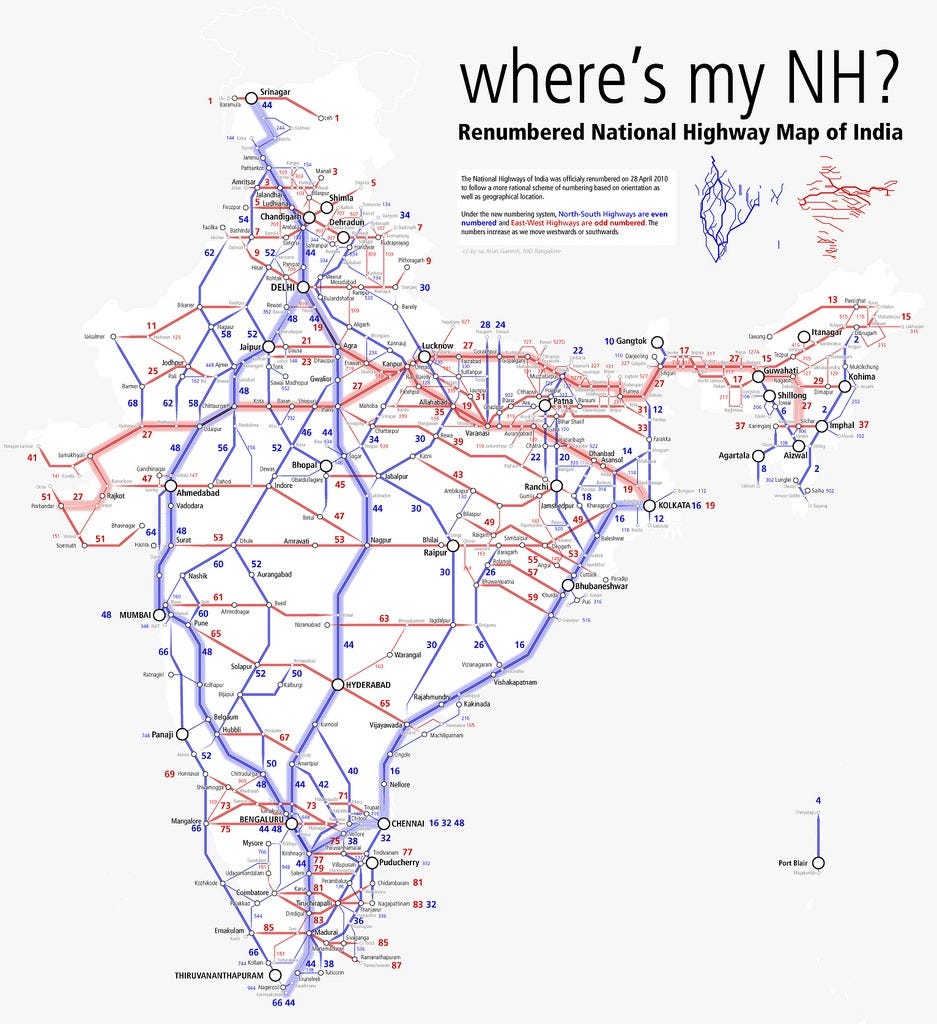

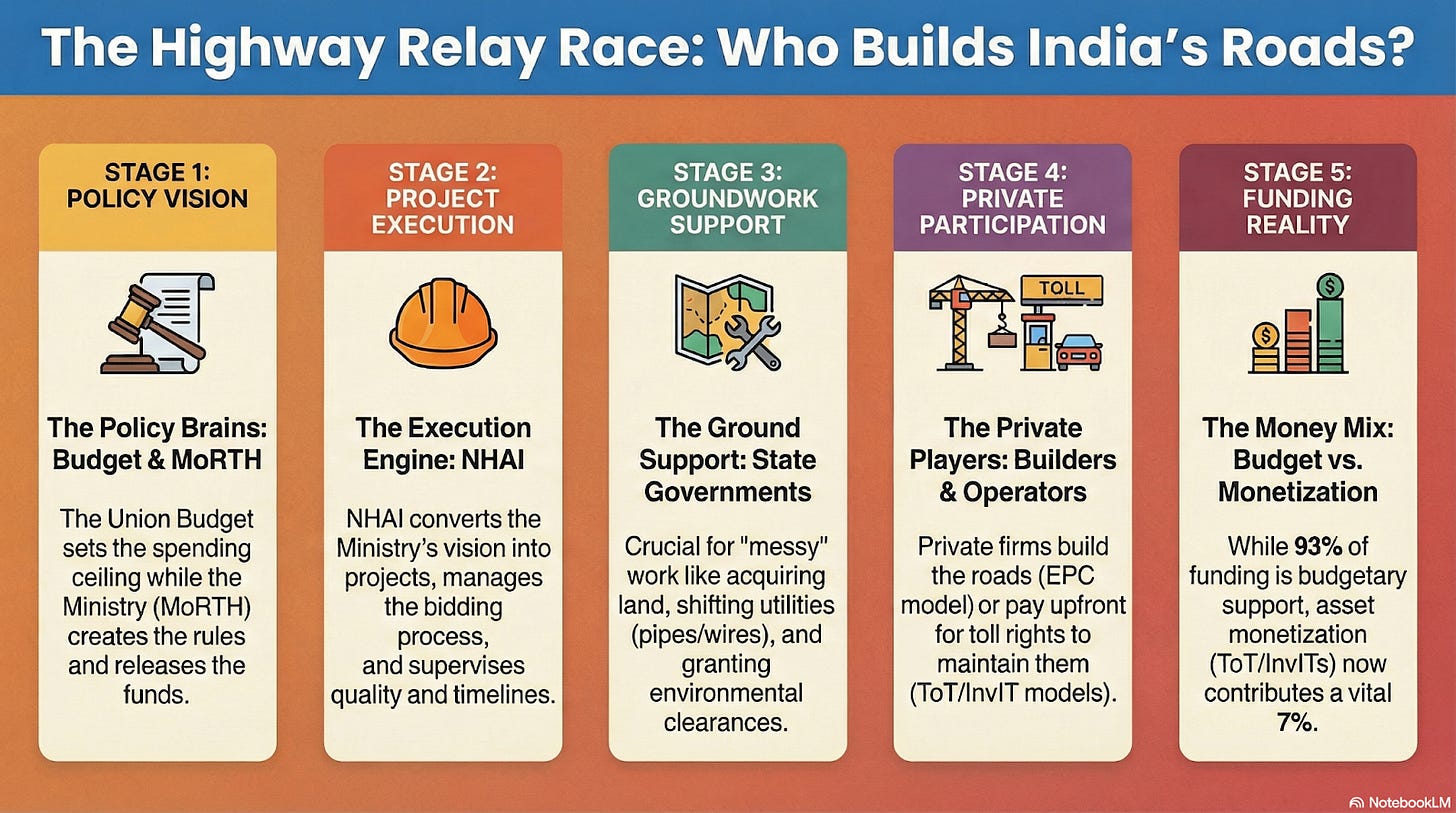

When you hear about the government building roads, behind the scenes, there’s a relay race: money, permissions, and responsibility keep getting passed from one hand to another. To keep it simple, let’s stick to National Highways (NH) — the big inter-state corridors you see with “NH” numbers. These are managed by the central government, even though they physically run through states.

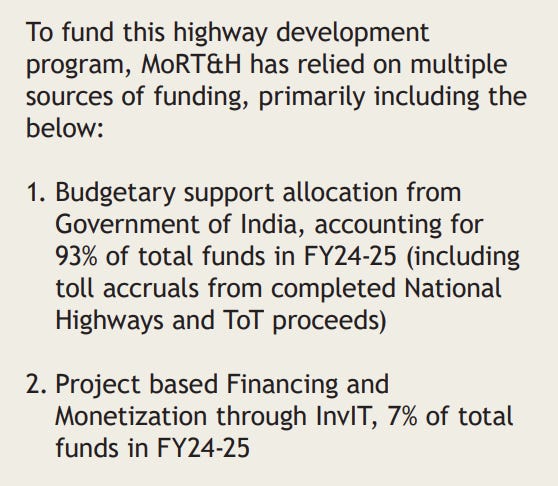

The story kicks off, every year, with the Union Budget. This sets the overall outlay for roads and highways: what will be spent on new roads, and for maintaining existing ones. That number, in practice, becomes the ceiling for how much fresh construction can be pushed.

Now, the Budget isn’t the only source of money. There are tolls, obviously — though most of that is used for either maintaining existing roads, or servicing debt. Government agencies like NHAI can also theoretically take loans, but that stopped in 2023.

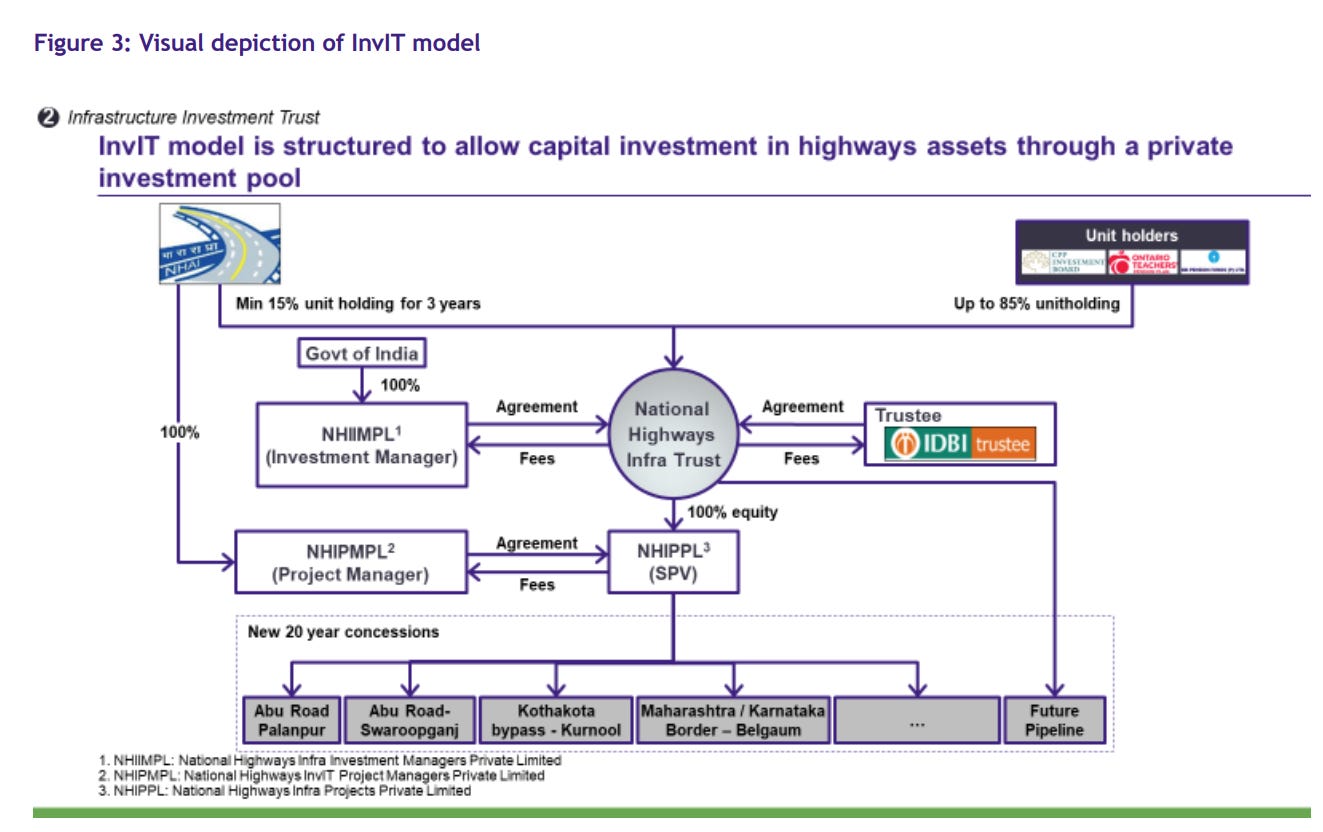

So, if you want to go beyond what the budget permits, the only other route left is project-based financing and monetisation, through InvITs. Over time, such monetisation has become a major part of the government’s plan, making up roughly 7% of the funds going into road development. It’s a sleeping giant: never enough on its own, but important support if India wants to build more roads within its budget.

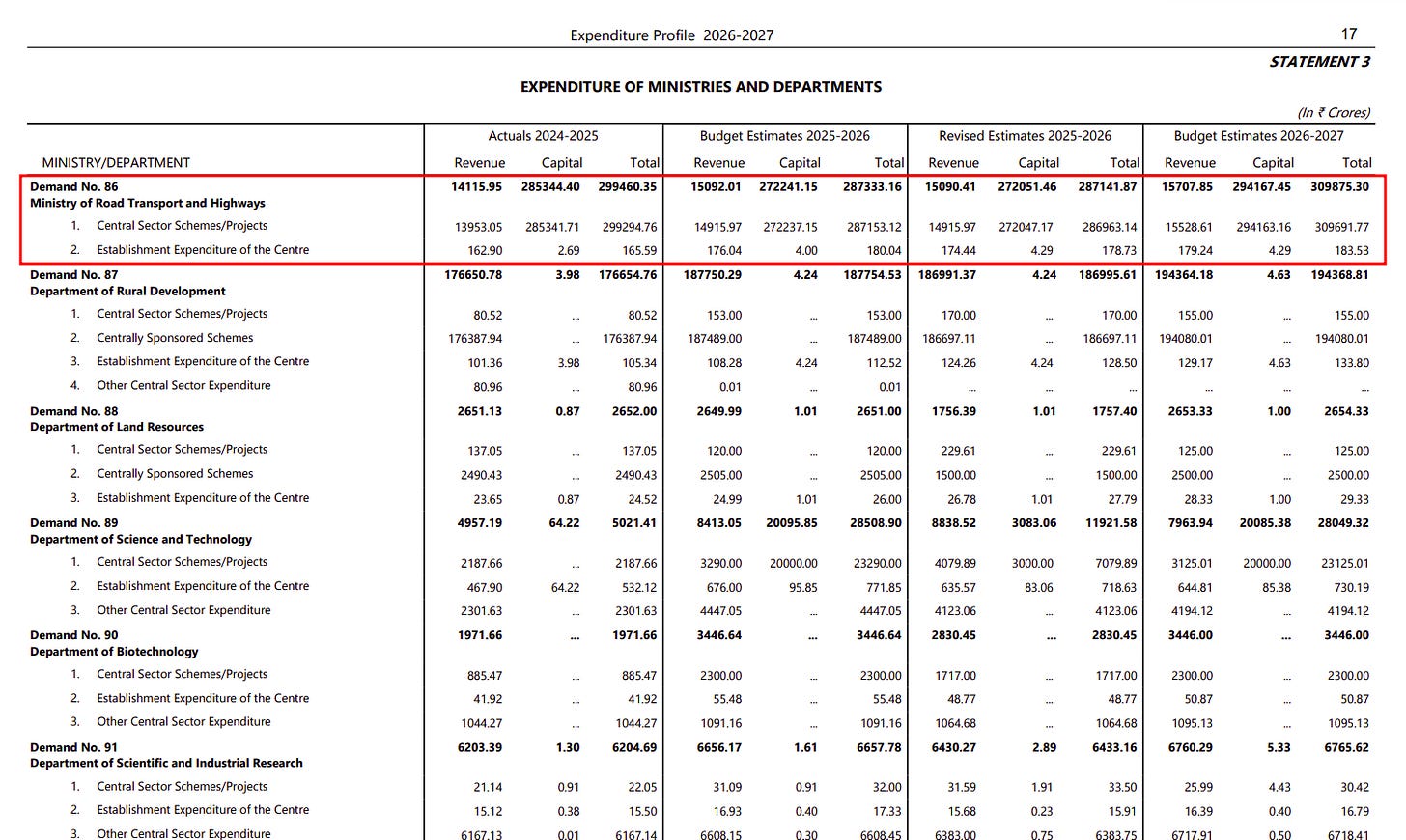

The budget sets broad expectations. The actual cheque-writing happens at the ministry. The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH) is the policy boss — the parent ministry responsible for the whole machine. When you hear big claims in the budget speech about thousands of crores being set aside for roads, look closer and you’ll see that money being allocated to MoRTH.

There’s a lot that MoRTH does. At a high level, it decides which corridors matter, and what projects get fast-tracked. Then, it approves specific projects and the framework around them — the contracting model being used, the broad rules of tolling and concessions, and so on. And finally, it controls how the money promised is actually released and spent.

MoRTH, in short, is the policy brain taking key decisions. But it doesn’t actually build roads. The job of execution goes to the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI).

NHAI takes the ministry’s vision and turns it into actual projects, packaging them into tenders. What begins as a big highway plan is broken, now, into smaller stretches, with granular plans and clear timelines. Then, NHAI runs a bidding process to select contractors. And as the road is built, it supervises the work — checking quality, monitoring milestones, and making payments.

Now, while National Highways are a central subject, state governments have power over the physical land they pass through. They inevitably get pulled into the process, handling land acquisition, and permissions for shifting utilities — power lines, water pipes, telecom, and other messy stuff. And there is a mountain of other coordination: environment and forest clearances, railway crossing approvals, permissions around water bodies or coastal zones, and so on. Nothing moves without all of this being handled.

Finally comes the actual physical construction work — which is often handled by a private contractor. Often, at least for national highways, infrastructure companies take up “EPC” (engineering, procurement, construction) contracts — or contracts of other sorts. We’ll get to those soon.

Even once the road is built, the job isn’t over. It needs maintenance, and a solid command over operations, like toll collection. That’s why multiple models exist. That’s where the monetisation question we began with shows up.

How a national highway actually gets built

You could think of every new highway project as one blunt question: who puts money in first, and who earns later? That decides the model under which the road is built (and later, maintained).

EPC = Engineering, Procurement, Construction.

Let’s start with the simplest — where the government, via NHAI, says, “we want this road built.” It then invites bids from contractors. The contractor builds it, gets paid for reaching milestones, and then exits once the ”defect liability” period is over.

All this while, the road is fully under NHAI / government control. It’s convenient, with fewer moving parts. And with control, quality is easier to enforce.

But there’s a brutal downside. In such contracts, the government / NHAI takes the money risk upfront. It shells money out regardless of what future traffic and toll collections look like. That’s fine in theory; roads aren’t businesses meant for toll revenue. They’re public goods. But that shrinks how much the government can do. A large chunk of cash gets locked up upfront. As a result, you end up building fewer roads with the same budget because money becomes the bottleneck. That money only comes back later, from tolls, and more broadly, from its wider economic spillover.

At the other end, the contractor takes on execution risk: can they build the road on time, to spec, without messing up? Their payments depend on hitting those milestones. The cheaper they can do so, the better the margin they can earn. Companies like Larsen & Toubro (L&T), Dilip Buildcon (DBL) and G R Infraprojects have built big businesses around this.

BOT = Build–Operate–Transfer.

If NHAI doesn’t want to lock all that money up, it can ask private developers to build a road with their own money, and then operate and maintain it for some time — usually 15–20 years. As compensation, the developer gets the right to collect tolls for that time. The road is only handed to the government after that.

In short: the private player takes both, the money risk and the execution risk, and earns it back through tolls over a period.

This is convenient for a government, because it avoids heavy spending — so you can build more roads faster, without the budget choking the system. But on the flip side, it’s a tricky deal for a private player. Their revenue is tied to future traffic and tolls — which aren’t guaranteed. If traffic doesn’t show up as expected, those toll collections don’t show up either.

Those risks could appear for any reason: alternate roads or expressways opening nearby; changes in toll rules; an expansion of exemptions; and so on. Since the government isn’t taking toll-collection risk here, it doesn’t feel the pain of shifting policy. The private player does.

HAM = Hybrid Annuity Model.

Neither option is perfect. The government doesn’t want to spend large sums of money, but private players think very hard before taking on government-scale risk. And so, in between, is the “HAM” model — which splits the burden.

In this mode, the government, through NHAI, pays a portion (40%) during construction, while the developer funds the rest. That is, both put money in upfront. Once the road is built, tolls are collected by the NHAI / government. The developer gets paid back through fixed annuity payments from NHAI over many years — while operating and maintaining the road during that period. The payment is guaranteed by NHAI, subject to performance.

Here, the developer’s return isn’t a bet on traffic. If they can build the road properly, without delays, and maintain it well, they keep getting a predictable cheque from NHAI.

To the government, this has some of the downsides of standard EPC contracts, even if in dilute form. It pays some money upfront. In exchange, it does get a “live asset” which throws off cash for decades through tolls. But the cash comes in slowly over time. Until then, that is capital which is locked up, and can’t be put into more roads.

So the government gets creative. It tries to pull future toll cash forward into today’s money. That’s basically the backbone of its asset monetisation plan.

ToT = Toll-operate-transfer

In the ToT model, an operator pays NHAI a lump sum upfront, and in exchange gets the right to collect tolls for 20-30 years. They also take on full maintenance obligations for that period.

Unlike everything we’ve spoken about so far, these contracts draw private capital into managing completed assets, not building them. The road already exists. It’s only being monetised. That gives the government money upfront, to redeploy elsewhere, while the operator gets a stream of future cash flows.

Here, the operator bears the risk of both maintaining the road and collecting tolls. It can subcontract the work, sure — but in the end, the operator is on the hook for the road staying in shape and the numbers working out.

Another is doing the same thing through InvITs (Infrastructure Investment Trusts). That’s basically the same idea, but in a fancier wrapper. In an InvIT transaction, the project company holding the tolling rights to road assets are transferred into a trust. The trust raises money by issuing units to investors. From that point on, the toll income belongs to the trust — and to its unitholders.

Essentially, in such a construct, future toll cash flows are packaged and sold to investors. That’s where the government gets its liquidity.

And that’s basically what’s happening with the RIIT deal.

Back to the headline

NHAI sponsored an InvIT called RIIT. RIIT won the right to collect tolls on — and maintain — five highway stretches. In return, it agreed to pay NHAI ₹9,500 crore. Now RIIT gets those tolling rights for the five stretches. To pay for this, RIIT is raising money — some equity, some debt. It also plans to IPO in February. So NHAI gets cash today; investors get a claim on toll cashflows tomorrow.

RIIT functionally becomes a financing vehicle for NHAI, while tolling and maintenance continue without NHAI needing to run the asset directly.

It’s a win-win-win for everyone.

Tidbits

India retail inflation at 2.75% in January under new CPI series

India’s retail inflation stood at 2.75% in January 2026 under the new 2024-base CPI series. Food inflation rose 2.13%, ending months of decline, mainly due to a sharp jump in tomato prices, while core inflation eased to 3.4%. Economists expect inflation to rise slightly in coming months but remain within RBI’s 2–6% target band.

Source: Business StandardRolls-Royce plans expansion, engine co-development in India

Rolls-Royce said it will scale up operations in India, exploring co-development of a next-generation 120 kN combat jet engine with full technology transfer and IP ownership for India. The company is also looking at partnerships to localise engine manufacturing for the Army, Navy and Coast Guard, aiming to boost jobs and domestic capabilities.

Source: The Hindu BusinessLine

Govt switches ₹75,500 crore FY27 bonds with 2040 security

The government conducted a bond switch with the RBI, buying back over ₹75,500 crore of securities maturing in FY27 and issuing a longer-term 8.30% GS 2040 bond instead. The move helps spread out repayments, reduce rollover risk, and smoothen the Centre’s debt maturity profile amid heavy upcoming redemptions.

Source: Business Standard

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Kashish

We’re now on WhatsApp!

We've started a WhatsApp channel for The Daily Brief where we'll share interesting soundbites from concalls, articles, and everything else we come across throughout the day. You'll also get notified the moment a new video or article drops, so you can read or watch it right away. Here’s the link.

See you there!

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Do the level of corruptions commonly encountered in building city roads (Banglore's infamous craters) also exist in these National Highways? can you write more about these aspects as well?