Tata Power's big ambitions, quick commerce, no BRICS currency and more | Who said what?

This post might break in your email inbox. Read the full post in web browser by clicking here.

Have you ever wondered what industry leaders or policymakers really mean when they say something? Their words often carry hidden layers of meaning, hinting at things that aren’t immediately obvious. That’s exactly what we aim to uncover here on "Who Said What."

Today, we’ve got 6 interesting comments to share with you.

Prefer video? you can watch it here:

Tata Power’s big ambitions

Praveer Sinha, the CEO of Tata Power, recently said, “We are looking at a profit after tax of over ₹10,000 crore by 2030 from a profit of ₹4,200 crore last year.”

That’s more than double their current profits. Naturally, this made us wonder—why would he make such a bold statement? What’s the plan to achieve such massive growth in a relatively short time? And most importantly, is it even realistic?

So, we did a little digging to find some answers.

Let’s start with some context. Tata Power, India’s largest vertically integrated power company, works across the entire electricity value chain. They’re involved in everything—generating electricity, transmitting it across the country, distributing it to homes and businesses, and even trading power. In short, they play a major role in ensuring electricity reaches us, from start to finish.

The real engine behind their future growth, though, is their big shift towards renewable energy. Right now, Tata Power generates 6.7 gigawatts (GW) from renewables. By 2030, they’re aiming to more than triple this, ramping it up to 23 GW.

This shift isn’t just about going green—it’s a smart business move too. Unlike coal plants, renewable energy projects are much cheaper to run once they’re up and running since there’s no need to keep buying fuel. Add to that the growing pressure from global and national policies to cut carbon emissions, and renewables aren’t just the environmentally friendly choice anymore—they’re becoming the more cost-effective one as well.

To pull off this massive renewable energy expansion, Tata Power is pouring significant investments into building new solar and wind farms. But generating renewable energy is just one piece of the puzzle. Many of these projects are in remote areas, far from the cities and industries that need the electricity. That’s why Tata Power is also focused on upgrading its transmission and distribution networks to ensure the power reaches where it’s needed most.

Right now, Tata Power operates 4,633 kilometers of transmission lines, which carry electricity from power plants to regional hubs. By 2030, they plan to more than double this, expanding to 10,500 kilometers. This upgrade is crucial to ensure that electricity from their new renewable energy projects can reliably reach cities and towns where it’s needed.

Distribution, which involves delivering electricity from regional hubs to individual homes, businesses, and factories, is also a big part of Tata Power’s growth plan. They aim to triple their customer base from 12.5 million to 40 million by expanding into states like Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. Each new customer adds steady, long-term revenue from electricity bills.

Of course, this ambitious growth comes with a hefty price tag. Tata Power plans to invest ₹1.46 lakh crore by 2030 to hit these targets. The lion’s share—₹87,600 crore—will go into renewable energy projects, while ₹29,200 crore will be used to upgrade their transmission lines.

The rest of Tata Power’s investment will go toward improving distribution networks and developing technologies like pumped storage, which works like a giant battery, storing and releasing electricity as needed. To fund these projects, Tata Power plans to use a mix of loans, equity, and the sale of non-core assets, such as overseas coal and hydro plants.

This aggressive shift toward renewables isn’t happening in isolation—it’s part of a larger global trend driven by government policies and market incentives. At COP29, global leaders discussed phasing out fossil fuels and set ambitious renewable energy targets. India, for instance, has committed to achieving 500 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2030. Tata Power clearly aims to position itself as a major player in this transformation.

There’s also a strong financial upside. Renewable energy projects often come with long-term Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) that lock in stable revenue for 20-25 years. For instance, Tata Power can supply electricity to governments or large industries at fixed rates, ensuring predictable income over the project’s lifespan. This is far more stable compared to coal plants, where profits can fluctuate wildly due to volatile fuel prices. Plus, as mentioned earlier, solar and wind farms don’t need constant fuel purchases, making them much cheaper to run in the long term—especially with coal and gas prices rising unpredictably.

But Tata Power isn’t the only one pushing hard into renewables. Competitors like Adani Green Energy, NTPC, and Reliance Industries are also making bold moves. Adani Green Energy is targeting 45 GW of renewable capacity by 2030, backed by a $100 billion investment in renewables, including a massive 50 GW energy park in Gujarat.

NTPC Limited, India’s largest power producer, has its own ambitious plans, aiming to install 60 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2032, with half of its total capacity coming from non-fossil sources.

Tata Power is also exploring cutting-edge solutions like green hydrogen, waste-to-energy projects, battery storage, and even nuclear energy to diversify its portfolio further.

Meanwhile, Reliance Industries has its sights set on establishing 100 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2030, with a strong focus on solar. They’re building a complete solar manufacturing ecosystem—from polysilicon and wafers to solar cells and modules. This not only supports their own projects but also positions them to dominate the supply chain for other players in the industry.

Recently, Reliance has already spent more than half of its committed ₹75,000 crore in its new energy business.

Amidst this fierce competition, Tata Power’s strength lies in its integrated model. The company isn’t just generating power—it’s also building the infrastructure to deliver it and manufacturing the solar panels it uses, giving it greater control over the entire process.

Tata Power’s ambition to more than double its profits by 2030 is deeply connected to India’s broader energy transition—and the global push toward clean energy as well.

Dabur’s worry

Dabur’s chairman, Mohit Burman, recently told Economic Times, “We have witnessed a marked shift in consumer-buying patterns in favour of emerging channels like quick commerce. While this has resulted in the emerging channels growing at a higher pace, it has also put general trade under stress.”

In simpler terms, he’s pointing out that more people are turning to quick commerce apps like Blinkit and Zepto, which is putting pressure on traditional kirana stores.

Let’s set the scene for a moment. Ten years ago, quick commerce wasn’t even a thing. It barely existed.

Quick commerce really took off during COVID, transforming from a “last-minute savior” to an everyday essential. These platforms have become so fast and efficient that even Amazon’s one-day delivery feels slow in comparison. They’ve completely changed how we shop—whether it’s for groceries (raashaan) or gadgets like the latest iPhone.

But it got me thinking—are these platforms killing kirana stores? It’s a question that sparks some pretty intense opinions.

One report suggests that 59% of kirana stores have been impacted by quick commerce. On the other hand, Aadit Palicha, the CEO of Zepto, says this idea is flat-out wrong.

Here’s his take: Between FY23 and FY24, India’s grocery and household essentials market grew by $46 billion. Quick commerce accounted for less than $5 billion of that growth. The remaining $41 billion? It went to kirana stores.

Palicha argues that this proves the narrative about quick commerce hurting kiranas doesn’t match the data. In fact, he says kiranas are actually growing alongside quick commerce, thanks to India’s booming consumption.

But honestly, it’s hard to say what the real impact is because we just don’t have enough data. Most of the retail market—especially kirana stores—is unorganized, which makes it tricky to measure accurately. If I had to take a few educated guesses, here’s what I’d say:

Quick commerce is definitely a game-changer, and sure, it might have cut down on those small grocery runs we all used to make. But let’s not forget, quick commerce is only available in a handful of cities. So, claiming it’s affecting all kirana stores across the country feels like a stretch.

On the flip side, you could argue that most high-value purchases happen in top-tier cities, which could mean there’s some truth to the idea that quick commerce is eating into kirana store revenues. But again, without solid data, it’s tough to confirm.

What’s undeniable is the massive amount of money flowing into quick commerce platforms in the last couple of years—especially recently. It’s clear that something big is brewing here. Maybe quick commerce is affecting kiranas a little right now, but it doesn’t seem to be on a massive scale yet. As for the future? It’s anyone’s guess, but it’ll definitely be interesting to watch how this unfolds.

Speaking of quick commerce, Dinshaw Irani, the CEO of Helios Capital, had an interesting take during a recent interview with Economic Times. Let’s dive into that.

Dinshaw Irani, CEO of Helios Capital, recently shared an interesting perspective during an interview with Economic Times. He said, “The compression in margins for most of these established brick-and-mortar players in the consumer space has been because of the consumer tech companies. Quick commerce, food delivery, all these spaces are going to look very exciting. In fact, quick commerce is something which is really homegrown. Globally, there are not many proponents of this kind of business, so it has done phenomenally well in India.”

These quick commerce platforms are tapping into the growing demand for convenience, letting people buy what they need without planning ahead or even stepping outside their homes. But this convenience comes at a cost for traditional retailers, whose business models rely on consumers physically visiting their stores, buying in bulk, and benefiting from value pricing. Quick commerce, with its speed and hyperlocal focus, has tightened margins and reduced footfalls for these brick-and-mortar players.

Deepak Shenoy, founder of Capitalmind, had also tweeted about the broader impact of internet companies on competition. To paraphrase, he mentioned how these internet-driven businesses have made it easier to compete with and even outpace large incumbents. The shift to tech-based solutions like quick commerce seems to embody this idea perfectly, as they’ve managed to disrupt well-established retail giants in a remarkably short span of time.

The first name that comes to mind when we talk about quick commerce disrupting traditional retail is DMart. As the undisputed king of offline grocery retail in India, DMart is now feeling the heat from platforms like Blinkit and Zepto.

During DMart’s first quarterly earnings call this year, CEO Neville Noronha openly acknowledged the growing influence of quick commerce. He said, “We don’t intend to do any quick commerce. Our model is pretty robust… But will I say there’s no impact? Maybe a 1%-1.5% same-store sales growth impact in some metro locations.”

In their second quarter press release, DMart doubled down on this point, stating, “We clearly see the impact of online grocery formats, including DMart Ready, in large metro DMart stores which operate at a very high turnover per square feet of revenue.”

This acknowledgment is significant. It highlights how even a giant like DMart, with its highly efficient model, isn’t entirely immune to the effects of online grocery platforms. While the impact might seem minor for now, the fact that it’s being acknowledged at all speaks volumes about the shifting dynamics in India’s retail landscape.

Pretty interesting, right? What do you think—Is quick commerce really eating into kiranas, or is it just another layer in India’s evolving retail landscape? Let us know your thoughts in the comments!

Dr. S. Jaishankar on BRICS currency

When India’s External Affairs Minister, Dr. S. Jaishankar, said, “We have no interest in weakening the dollar at all,” it probably flew over most people’s heads. Why would anyone even bring up the idea of “weakening the dollar”? And what does it mean for India—or for anyone else? Let’s break it down step by step.

First, let’s understand why the dollar is such a big deal.

The U.S. dollar isn’t just America’s currency—it’s the world’s default currency. This means that most international trade—whether it’s for oil, wheat, or iPhones—is conducted in dollars. To put it in perspective:

About 88% of global forex transactions involve the dollar.

Around 60% of central bank reserves worldwide are held in dollars.

More than 50% of global trade is invoiced in dollars.

In short, the dollar isn’t just another currency—it’s the backbone of the global economy.

Banks around the world hold dollars in their reserves to settle international trades, and central banks stockpile dollars to stabilize their currencies. So, when Jaishankar says India has no interest in weakening the dollar, he’s essentially saying that India benefits from the dollar staying stable and strong.

Let’s flip the situation to understand why some countries might want to weaken the dollar.

Countries like Russia and China have long criticized the dollar’s dominance, arguing that it gives the U.S. too much power. Because the global financial system revolves around the dollar, the U.S. can impose sanctions that cut countries off from trading. For instance, when Russia faced sanctions, $300 billion of its central bank reserves were frozen by Europe and the U.S. A weaker dollar—or the rise of an alternative currency—would reduce America’s financial leverage.

But India doesn’t face those issues. On the contrary, a stable dollar is vital for India’s trade and economy. That’s why Jaishankar is quick to clarify that India has no plans to weaken the dollar or challenge its role.

His comment ties into a broader global conversation about “de-dollarization,” a term used to describe efforts to reduce reliance on the U.S. dollar for trade and financial transactions. Countries in the BRICS group, for example, have floated the idea of creating an alternative currency for trade among member nations.

Russia, heavily impacted by U.S. sanctions, is keen on finding alternatives to the dollar. Similarly, China has been promoting its currency, the yuan, for global trade—though with limited success. However, Jaishankar’s statement makes it clear that India is not on board with destabilizing the dollar.

There are several reasons for this:

India’s Trade Ties with the U.S.

The U.S. is India’s largest trade partner, with bilateral trade exceeding $128 billion. Most of this trade is settled in dollars. An unstable dollar could disrupt this system, making trade more expensive and unpredictable.

Energy Imports

India imports over 85% of its oil, with payments almost exclusively made in dollars. If the dollar’s value were to fluctuate, oil prices could become volatile, potentially leading to inflation back home. Since energy costs directly impact transportation and food prices, this could spell disaster for the economy.

Remittances

India receives over $100 billion annually from Indians working abroad, a significant portion of which comes in dollars. A weaker dollar would mean less value for these remittances, directly affecting millions of families.

Dollar-Denominated Debt

Indian companies and banks borrow extensively in dollars. If the dollar’s value became unstable, it would create uncertainty in repayment schedules and financial planning, adding to economic stress.

Bond markets

India’s corporate bond market is surprisingly underdeveloped for an economy of its size. SBI Chairman C.S. Setty pointed this out recently, highlighting how companies struggle to raise long-term funds through bonds, despite India being one of Asia’s largest economies.

Let’s break it down.

Banks like SBI primarily rely on short-term deposits, which makes it difficult for them to lend money for long-term needs, like 10-20 year loans for infrastructure projects or large-scale business expansions. Bonds offer an alternative. They’re essentially loans that companies take from investors, promising to pay regular interest and return the principal at maturity.

Despite this need, India’s corporate bond market isn’t growing as fast as it should. Even though SBI issued ₹50,000 crore in bonds this year, the overall market remains underdeveloped.

What’s Holding the Market Back?

Bias Toward High-Rated Bonds

Bonds in India are mostly issued by AAA or AA-rated companies, which are considered extremely safe. In FY22, 80% of bonds were AAA-rated, and 15% were AA-rated. That leaves out many companies with lower ratings but reliable track records, as investors perceive them as too risky.

Private Placements Dominate

Around 98% of corporate bonds in India are sold through private placements—offered directly to select investors rather than the public. While this is faster, it lacks transparency and makes fair market pricing difficult. Globally, public bond issuances are more common, encouraging better price discovery and wider participation.

Limited Investor Base

In India, corporate bonds are mainly bought by banks, insurance companies, and mutual funds. Retail investors—regular folks like us—rarely participate. This contrasts sharply with markets like the U.S., where individual investors actively buy corporate bonds, adding to the market’s dynamism.

Lack of Risk Management Tools

India lacks instruments like credit default swaps (CDS), which act as insurance for bonds. A CDS compensates investors if a company defaults on payments. Without tools like these, investors hesitate to take on bonds with lower ratings, shrinking the market further.

Despite these challenges, there are some bright spots:

Total outstanding corporate bonds have grown to ₹50 lakh crore by FY24.

Platforms like the Electronic Bidding Platform (EBP) streamline private placements.

Systems like the Request for Quote (RFQ) are improving transparency in bond trading.

New products like Tri-Party Repo agreements, allowing short-term borrowing with bonds as collateral, are gaining traction.

India’s secondary bond market—where bonds are traded after being issued—is lackluster. Most bonds are held to maturity, meaning they aren’t traded. This stifles market growth, and the average daily trading volume, at ₹5,722 crore in FY24, is tiny for a market of this size.

Regulators are stepping in with initiatives:

Allowing banks to hold corporate bonds under the Held-To-Maturity (HTM) category to reduce market fluctuation risks.

Lowering bond face values to attract smaller investors.

Why It Matters

India has ambitious goals, like becoming a $30 trillion economy by 2047. Achieving this requires massive infrastructure investments, which need a robust corporate bond market. While trading platforms and processes have improved, the key lies in creating a vibrant secondary market with diverse investors and active trading.

The corporate bond market is making progress, but there’s still a long way to go before it can fully support India’s economic aspirations.

Wage growth

V. Anantha Nageswaran, India’s Chief Economic Advisor, recently voiced concerns about how private sector companies are handling employee compensation. He said, “The staff cost of private-listed companies, whether it is information technology firms or general, has been coming down. In other words, compensation growth has become weaker and weaker.”

Nageswaran emphasized that while companies are posting record profits, they need to focus more on supporting their employees and making investments. He added, “Now it is time to engage in a good combination of capital formation and employment growth as well.”

In simpler terms, Nageswaran is saying that despite doing well financially, companies aren’t investing enough in their workers—a trend that could hurt both employees and the economy in the long run. He suggested a more balanced approach where businesses prioritize growth alongside job creation.

Ramani, CFO of TeamLease, offered a different perspective during a CNBC TV18 interview. She pushed back against the idea of widespread wage stagnation, saying, “For us, the salary inflation for the 3 lakh employees on our rolls has been consistently between 6% and 8% year-on-year. Only in IT, over the last one and a half years, has it slowed down to 2% to 3%, and that’s more of a correction after the COVID-era hikes.”

According to Ramani, the slowdown in IT sector salaries is more of an adjustment following the unusually high pay raises during the pandemic. Outside of IT, she noted, wage growth in most sectors has been steady. She also highlighted a positive trend—formal job creation is growing, with more jobs moving from the informal to formal sector. This shift ensures employees gain access to benefits like provident fund contributions and other social security perks.

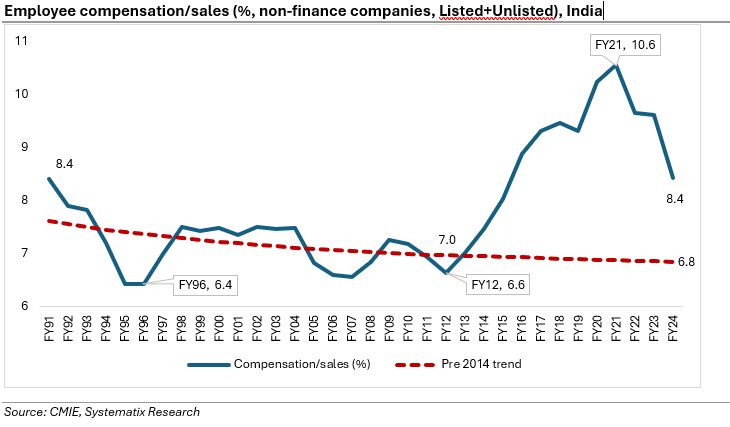

Dhananjay Sinha, Head of Research at Systematix Group, weighed in with a LinkedIn post, offering a historical perspective on the link between employee pay and company sales. He wrote, “Contrary to common understanding, compensation growth lags sales, rising slower in an up-cycle and falling less during the down-cycle.”

In simple terms, this means that during economic booms, employee wages don’t grow as quickly as company sales. On the flip side, during downturns, wages don’t drop as sharply as sales.

Sinha also pointed out that the slower wage growth isn’t the only factor behind weak urban demand. He cited automation and digitization as significant trends reducing the need for workers in certain areas, further impacting wage growth and job opportunities.

Sinha also pointed out an interesting trend: during the pandemic, when sales slowed down, the share of employee pay compared to sales actually increased. However, as sales recovered in FY24, this share dropped. He suggested that this isn’t necessarily because companies are suppressing wages but rather because they’re becoming more efficient.

Sinha concluded that weak urban demand likely has deeper causes beyond just employee pay. He pointed to larger economic challenges, such as structural shifts in the economy and the ongoing impact of automation and digitization, which are reshaping how businesses operate and reducing the need for certain types of jobs.

That’s it for this edition, do let us know what you think in the comments and share with your friends to make them smarter as well.