SEBI isn't a big fan of digital gold

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

What do you buy when you buy digital gold?

From stone to gas: India’s coal gasification gambit

What do you buy when you buy digital gold?

Through the last decade, there’s been a wave of new financial products: one-tap SIPs, “round-up” investing, and rewards for paying rent by card. One part of this wave was “digital gold.” It came with a nice, shiny pitch (much like gold itself): why keep your savings in a bank when you can buy pure, 24-karat gold on an app in under a minute? Just tap the “₹100” button and that amount of gold will sit in a vault “in your name.”

In a country that loves gold, this was hugely attractive. Look at this year alone — according to ET Wealth, UPI transactions in digital gold ballooned from ~₹760 crore in January to nearly ₹1,180 crore by August 2025.

But as they say, not all that glitters is gold. These deals might gleam on the surface, but their insides are murky. See, at its heart, digital gold is not a regulated product. There’s nobody policing those apps to ensure that they play fair by you. And yet, because it was sold so aggressively across apps, many unsuspecting customers jumped in without questioning the offer.

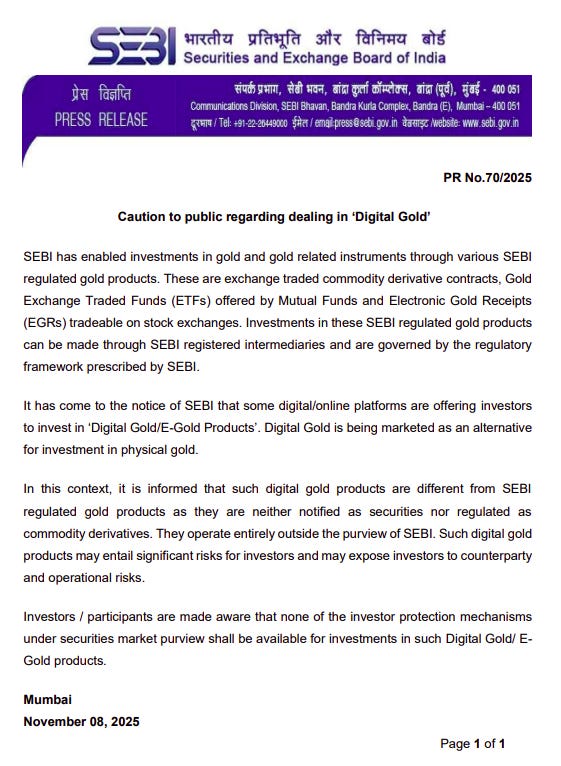

That’s why SEBI recently put out a caution note regarding Digital Gold.

The note was a reminder to everyone: India already has regulated ways to invest in gold — from gold ETFs by mutual funds, to electronic gold receipts (EGRs) you can trade on exchanges, to even gold derivatives on commodity exchanges. The “digital gold” you see on many apps, however, is not one of them. It sits outside SEBI’s rulebook.

In fact, back in the Union Budget for FY 2021-22, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman had announced that SEBI would be made the regulator for a dedicated gold exchange. That announcement signalled that the government was thinking seriously about bringing order and transparency to gold trading. So far, that project hasn’t gone anywhere. But the need for one very much remains.

So, what exactly is the problem with digital gold? Let’s dive in.

Regulation

When you buy a stock through a broker like us, your shares don’t actually sit with us. They’re in a demat account that’s maintained with government-backed depositories — CDSL or NSDL. If we were to go down some day, by some misfortune, your shares would stay safe. They would remain in a completely separate system, with legal protections and audits. Your assets aren’t mixed with our balance sheet.

Gold ETFs work in the same way. While you see your units of such an ETF on your broking app, there’s a whole regulatory backend underneath — trustees, custodians, auditors, daily NAV calculations, expense ratios — all of which have to be disclosed. This is all governed by SEBI. You aren’t just trusting one company’s word; you’re buying into a system bound by clear regulations.

On the surface, digital gold looks and feels the same. A digital gold app might tell you that they’re buying physical gold against every Rupee you give them, and are storing it in a vault somewhere, with a private contract marking the transaction. Maybe there’s even a trustee involved. Your account will tell you exactly how much gold you own. Sounds legitimate, right?

Well, it might look that way — but your own that gold under the terms and conditions that the company sets. Anyone can start an app and sell digital gold to you. There’s nobody checking after them. They don’t come under any SEBI framework, nor are they vetted by any other verified legal institution. If that company is running well, it might not make a difference. But if it fails, you’re unprotected. You can’t recover “your” gold. All you have is a private contract, and the very specific terms it contains. There’s no wider framework to fall back on.

In other words, you’re taking on a counter-party risk. You’re betting all that money purely on the trust you have in an app.

Even if you trust a digital gold seller, there are major questions that you might not know the answer to. For instance: is your gold actually segregated, or is it pooled with everyone else’s? Are you a beneficial owner of specific bars with serial numbers, or just a general claimant on a big pile? Without a legal backstop, there are no standards to any of this.

The pricing problem

See, regulated markets force transparency. An ETF must publish a daily NAV. You see buy and sell prices on the exchange. The expense ratio is well documented. Dig around, and you’ll know exactly what you’re buying.

But without regulation, this outside push for transparency doesn’t exist with digital gold.

Consider this: the moment you tap “buy” on an app, you’re treated as if you’re purchasing physical gold — just that you’ve deputed someone else to do so and keep it on your behalf. Physical gold, under Indian tax law, attracts 3% GST at the point of purchase. There’s no way around that. Whether you ever see a bar or coin or not, you have to pay that tax because, legally, it’s a sale of goods, not an investment transaction.

And so, if you put ₹10,000 into digital gold, ₹300 of that immediately goes in GST. In a sense, you start your investment with your portfolio 3% down.

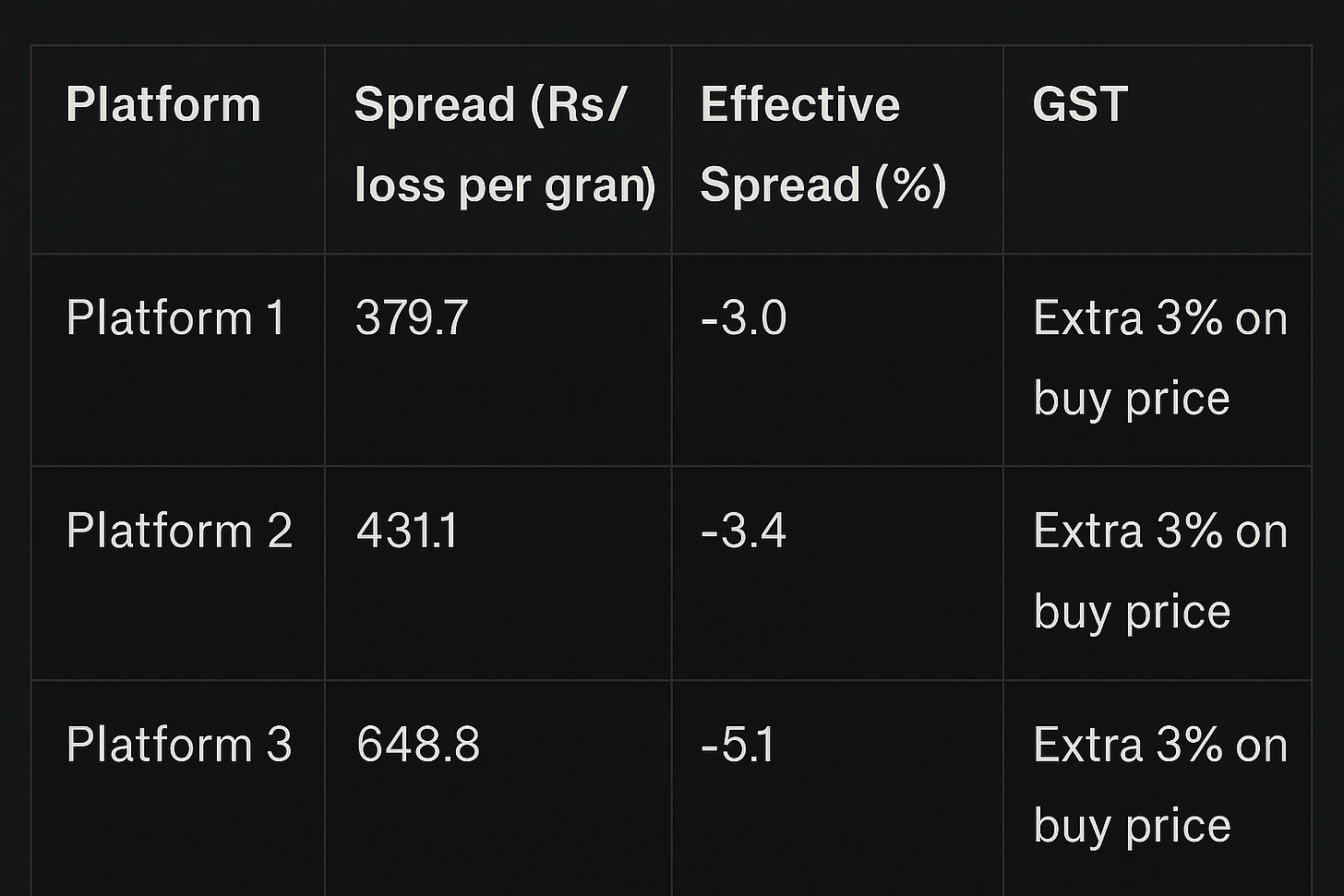

On top of that, add the spread. Since there’s no exchange or common price feed, each platform sets its own buy and sell quotes. They might say that they’re taking this to cover hedging, vaulting, insurance, and logistics, but in practice, if you buy gold and try to sell it back immediately, you’ll still get about 2–3% less than what you paid. That spread is how the platform earns.

Put that together. If you put in ₹10,000, ₹300 is gone in tax, and another ₹200–₹300 goes to the platform. You’re instantly looking at a ₹500–₹600 loss, as soon as you invest. In other words, your ₹10,000 “investment” only buys you ₹9,400–₹9,500 of gold.

Conclusion

SEBI’s note is a reminder that while digital gold might sound sleek and modern, underneath, it’s an unregulated product. You might choose to trust it anyway, but at the very least, you should understand the risk you’re taking on. If something were to happen to the platform selling that goal, there’s no safety net. There’s no SEBI or stock exchange to bail you out. Your only real recourse is to go through the normal court system, seeking the very same assets that all of the company’s creditors will be after.

If you’re looking for an exposure to gold, a ready alternative might be a Gold ETF. Just like digital gold, they give you a claim on a certain amount’s worth of gold. Unlike digital gold, however, they’re regulated, transparent, and liquid. You can buy them through any broker at a public price, and your holdings sit safely with the depository — far from the control of the broker that you bought them from.

From stone to gas: India’s coal gasification gambit

Throughout October, we had seen a series of headlines that, at first glance, barely made sense to us. The government was making a strong push for the “gasification of coal”. To this end, it recently opened auctions for sites where this could happen underground.

This made little sense to us. Coal was, as far as we knew, clearly solid. How would it become a gas? Why would you even try? Those questions launched us into a deep and fascinating rabbit hole.

Some of this, we realised, was intuitive. If you’ve ever tried to light a bonfire or start a barbecue, you’ve probably realised how unpredictable and messy burning something solid can be. Gases, in comparison, are relatively simple. They create an even flame that you can literally control with a knob — just look at your kitchen stove.

That is what India is leaning into. We’re trying to convert solid coal into a gas, called “synthesis gas,” or “syngas”: a mix of carbon monoxide and hydrogen. Not only is this potentially a better fuel source, it can also lend itself to a range of other industrial applications. This is, however, a challenging and controversial project, and success is not guaranteed.

How does coal turn into a gas?

Turning coal into a gas isn’t a new idea; we’ve been doing so since the 19th century. Ever noticed those old-timey gas-powered street lamps? These were all run on coal gas, or what was called “town gas”.

In fact, in large parts of the developed world, right until the 1970s, most homes and businesses would be connected to town gas pipelines — using it for lighting, heating, and cooking. In fact, it was only when we discovered large reserves of cheap natural gas that entire countries chose to switch over.

Suffocating fire

When something “burns”, at a molecular level, the heat is pushing it to react with any oxygen it can find nearby. To make coal gas, we take it half-way there. In a process called “partial oxidation”, we heat coal to very high temperatures — 700-1,600°C — but starve it of oxygen, so that it can’t burn well. The unburnt gasses this creates, once processed, are the “syngas” we want.

Here’s how it works.

Coal isn’t just carbon. It naturally contains a lot of water, and several volatile compounds — tars, methane and more. So, to begin with, we devolatilise coal. We heat coal up to 350-700°C, letting all of this escape.

This leaves us with a carbon-rich “char”. From there, to get to syngas, we need a lot of heat. And so, we start burning some of this char under limited oxygen —- between one-fifth to one-third the oxygen you would need to burn it completely. In this suffocated state, the coal only burns partly, creating a lot of carbon monoxide. But that’s enough to heat the mix up to extremely high temperatures.

Through this hot, oxygen-starved environment, you finally run a “gasifying agent” — a carefully controlled stream with small amounts of oxygen (or air) and steam. In a series of chemical reactions, the carbon in that char practically snatches away the little oxygen available, leaving behind a mix of hydrogen gas and carbon monoxide — both of which burn easily when exposed to more oxygen. Once cleaned, you get a gas that can burn cleanly.

Industrialising coal gas

Traditionally, most coal gasification happened in large industrial facilities, once it had already been dug out of the ground. This required large set ups, built around high-temperature, high-pressure steel “gasifiers”. Establishing such a set up could cost as much as $300-500 million.

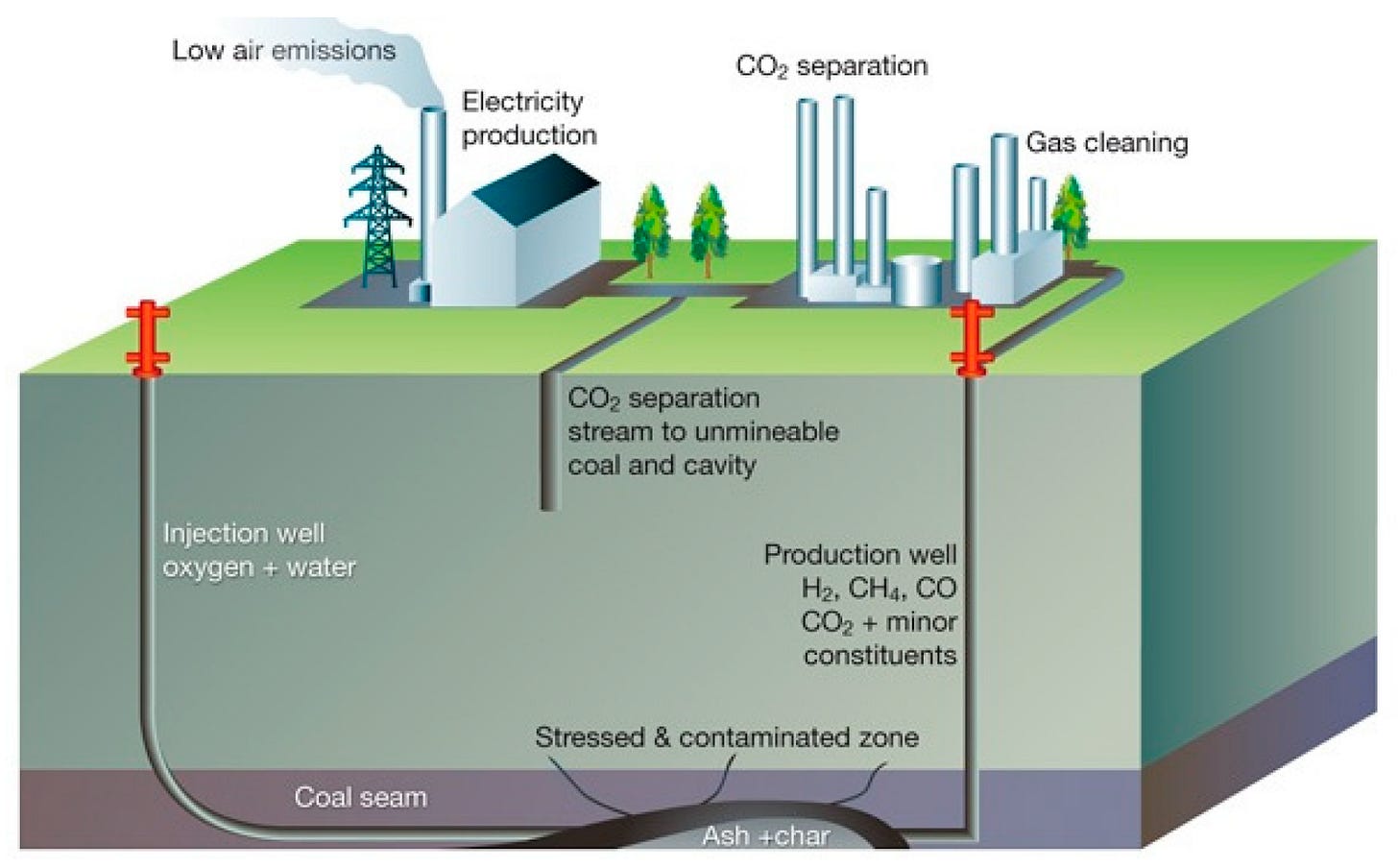

But we’ve also been experimenting with another possibility — one that eliminates the need to mine coal altogether. Instead of digging coal, bringing it to the surface and running it through sophisticated industrial machinery, one can gasify it inside the coal mine itself. You bore “wells” right into the coal seam deep underground, inject your gasifying agent straight in, and pump out syngas to the surface.

To be clear, this is far from easy. You’re basically lighting a large fire deep underground, where nobody can observe it directly, and trying to control how it spreads. This is exactly as hard as it sounds.

But it has a big advantage, which makes the method transformative: it unlocks “unminable” coal blocks. Something between one-sixth and one-eighth of the world’s coal reserves can be mined economically, using conventional methods. The rest are, for all intents and purposes, just geographical curiosities. They’re too deep or hard to access by a mining crew, or are in geologically sensitive zones that could easily cave in. Government estimates say that large parts of India’s coal — at least 40% — is currently unminable.

Gasification allows us to make those reserves useful.

Why should one gasify coal?

Coal is a dirty, bulky solid. Gasification turns it into a clean, versatile gas. It takes the same, finite carbon resource, and allows you to use it more intelligently — extracting energy and value, controlling pollutants, and more. Here is the promise:

Environmental friendliness

We’re in an era where climate change and escalating pollution levels are forcing us to rethink our use of coal-based power plants. And yet, coal is India’s only abundant energy reserve. We have ~378 billion tonnes of coal — enough to last us for ~147 years, at our current rate of extraction. Gasification gives us an alternative.

Syngas isn’t a clean fuel. It is made from coal, and contains all the pollutants that coal does — compounds of sulphur, nitrogen, mercury, and the like. But crucially, those pollutants are easier to deal with. Coal releases those pollutants upon burning, as a heavily diluted exhaust gas. At these low levels of concentration, it’s all but impossible to scrub out those pollutants.

In contrast, in syngas, you can remove the same pollutants before it is burnt. They’re still highly concentrated at this point, and are easier to separate out. Some, like Sulphur, can actually be sold as a by-product.

There’s a caveat, however. Burning syngas creates ~2.5 times as much carbon dioxide as you would by simply burning coal. Those environmental benefits only show up when you combine it with a carbon capture and storage program — which has never been deployed at any scale in India.

Industrial applications

Syngas can be burnt, but it’s more than a fuel — it’s a concentrated stream of carbon monoxide and hydrogen, the composition of which can be controlled — which makes it tremendously useful in industrial applications. In fact, the name “synthesis gas” comes from its ability to synthesise things.

For one, syngas can be an intermediate towards cleaner fuels — from simple gases like methane or hydrogen, to complex liquid fuels, like jet fuel or synthetic diesel.

It can also be used as a precursor for various chemicals. For instance, its hydrogen can be separated out, and used to make ammonia for fertilisers. Consider this: 40% of the world’s urea is made in China, though coal gasification. India, meanwhile, imports 7-8 tonnes of the fertiliser every year. Similarly, syngas can also be used to make methanol, which goes into plastics, resins and other products.

Since syn gas is oxygen-starved, it’s also a great “reducing agent”, which suck oxygen out of a product. This has major uses, for instance, in the steel industry.

The short point is this: right now, our coal is at best used to create electricity, and that too at low levels of efficiency. Those same reserves, however, can be made more flexible, and then used in creating a range of high value industrial products.

India’s coal gasification plans

In 2021, India came up with an ambitious plan: we would invest a total of ₹4 lakh crore by 2030, to set up enough capacity to gasify 100 MT of coal a year.

This promised to solve serious problems for us. We’re deeply energy starved — and rely on imports for most of our energy needs. We also spend heavily on importing urea, methanol, and other industrial products. Collectively, this amounts to billions in annual import exposure, as well as a deep strategic vulnerability. Gasification would solve all those problems in one go.

To a private investor, though, making investments in gasification would be a daunting affair. Gasification plants require a tremendous amount of upfront capital expenditure, with no expectation of return. Most modern gasification technologies are designed to work with much higher grades of coal than are available in India — leaving no easy plug-and-play solution that you could purchase. And any cheap source of natural gas can quickly run you out of business — as had happened in the United States, once it discovered shale gas.

This is why the government is offering major sops to anyone willing to enter the space.

National Coal Gasification Mission

The National Coal Gasification Mission tried to solve the many uncertainties of the gasification business comprehensively.

To make the upfront capital expenditure less daunting, it announced financial incentives of more than ₹8,500 crore. Half of that would go to PSUs, but the other half was earmarked for private players. The government is also offering a 50% rebate in the revenue it would otherwise take for those coal blocks.

That makes for the costs. But there was also a technological challenge: the quality of Indian coal is poor — with 30-45% ash content. This makes gasification dramatically harder: you have to spend much more per unit of syngas, and once you’re done, you’re left with large amounts of slag that you have to dispose of. Some countries, like South Africa, have been successful in working with poorer coal qualities. But ultimately, India probably required specialised technologies for our own grades of coal. We haven’t quite cracked this problem yet, but the government is sponsoring major projects to develop an indigenous gasifier.

Finally, it’s trying to remove the uncertainty around finding a buyer, by creating guaranteed demand. To this end, it has set up joint ventures between Coal India Limited and a series of PSUs — GAIL, SAIL, BHEL, and more — all of which will use coal gas in industrial applications. These could become guaranteed marketers of any syngas you could sell them.

The underground auctions

That brings us to the headlines we started with, which mark a major step ahead.

At the 14th round of India’s commercial coal mine auctions, which started late this October, the government auctioned 21 blocks that, for the very first time, were identified as having the “potential” for underground coal gasification. Before this, our gasification mission focused on surface gasification projects. The newest round, however, opens the door to underground gasification. In a sense, this marks a new frontier on what “mining” even means.

For anyone willing to try this new approach, the government is offering massive sops. Any bidder would get a discount on upfront payments, to be adjustable against future royalties. “Efficiency” parameters would be liberalised, and regulatory approvals fast-tracked.

The most critical, and controversial, component of this new policy, however, was that pilot underground gasification projects were exempted from environmental clearances. Normally, all coal mining projects in India must go through an environmental impact assessment, after which they must seek government clearance. This is a lengthy process. But for the first stage of a new underground gasification projects, the government did away with this completely.

This would strip away the biggest source of red tape and bureaucratic delays from the process. To the government, this was essential to simply get the experiment off the ground. At the same time, however, this made many environmental experts uneasy. This is an unproven technology, and could create major issues.

The biggest problem, perhaps, is the possibility of groundwater contamination. This has happened before. Underground gasification tests in the United States, for instance, started contaminating the surrounding groundwater from the pilot stage itself — as carcinogens like Benzene, phenols, heavy metals and other tars started entering surrounding aquifers. Similarly, in Queensland, Australia, such efforts were banned entirely in April 2016, after a pilot project caused serious environmental damage.

There are also other problems — from the possibility of land collapsing, to a high chance that one can lose control of the reaction process. With such risks, some consider it deeply dangerous to do away with environmental checks.

To be fair, however, the government isn’t creating a free for all. In its draft guidelines on underground gasification, it tried to ringfence against those dangers — requiring a pilot feasibility study, comprehensive monitoring of groundwater, and setting up online sensors to track any contamination in real time. This, hopefully, could limit some of the danger.

A fundamental reinvention

Will these auctions be successful? Will we actually gasify our coal?

On paper, coal gasification promises to make India’s dirtiest fuel more versatile, and to unlock reserves that would otherwise stay buried. If this experiment succeeds, we could create serious value out of our coal endowments, fuelling everything from power plants to chemical refineries. But that promise isn’t a guarantee. There are serious challenges still — environmental challenges, engineering challenges, economic challenges, and more.

Either way, this moment marks a turning point; a complete reinvention of how the dirty, bulky energy source works.

TIDBITS

India’s joblessness eases to 5.2% in Q2 FY26

Unemployment fell to 5.2% in July–September from 5.4% in the previous quarter, with rural joblessness at 4.4%. Self-employment rose to 55.8% of total workers, but youth unemployment climbed to 14.8%. The share of salaried jobs dipped slightly, showing continued stress in formal hiring.

Source: Business Standard

India proposes ‘country of origin’ filter for e-commerce

The government has proposed new rules requiring online platforms to add a ‘country of origin’ filter, allowing buyers to identify Indian-made goods easily. The move aims to give local manufacturers more visibility and boost the ‘Make in India’ initiative amid rising global tariff tensions.

Source: ReutersSEBI uncovers ₹100 cr fund diversion in SME IPOs

SEBI has found evidence of up to ₹100 crore siphoned from around 20 SME IPOs managed by First Overseas Capital Ltd (FOCL). Funds meant for business expansion were allegedly routed to promoter-linked entities. More enforcement orders are expected in the coming months.

Source:The Hindu BusinessLine

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Pranav.

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Have you checked out Points and Figures?

Points and Figures is our new way of cutting through the noise of corporate slideshows. Instead of drowning in 50-page investor decks, we pull out the charts and data points that actually matter—and explain what they really signal about a company’s growth, margins, risks, or future bets.

Think of it as a visual extension of The Chatter. While The Chatter tracks what management says on earnings calls, Points and Figures digs into what companies are showing investors—and soon, even what they quietly bury in annual reports.

We go through every major investor presentation so you don’t have to, surfacing the sharpest takeaways that reveal not just the story a company wants to tell, but the reality behind it.

You can check it out here.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Nice article, I started with digital gold yesterday but now will focus on it more....

Nice snippet, but the title does seem clickbait-y.

Digital gold can easily be mistaken to also include etfs

Eta:does*