SEBI has something to say about algo trading

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

SEBI wants to protect retail investors

Is debt good or bad?

SEBI wants to protect retail investors

SEBI has proposed a new framework to make algo trading more accessible for retail investors while keeping the market safe and fair. This move comes as more retail investors are starting to use algo trading, and several unregulated algo platforms have popped up, often promising unrealistic returns.

To give you a quick idea, Algo Trading uses computer programs to automatically buy and sell stocks based on set rules. For example, an algorithm might be set to buy a stock if its price goes above ₹100 and sell it if it drops below ₹95. This removes the need to watch the markets constantly and ensures trades happen quickly. In reality, though, these algorithms can get very complex.

The big advantages of algorithmic trading are speed and discipline. Algorithms can process huge amounts of data and place trades in milliseconds—much faster than any human could. Plus, they follow the rules without letting emotions get in the way.

In India, algo trading makes up about 70% of the total market volume. That sounds like a lot, right? But most of this comes from big players, like high-frequency traders, not retail investors.

Here’s what the latest SEBI draft circular says:

Brokers must get approval from stock exchanges for every algorithm before deployment. Once approved, each algorithm will be given a unique ID for easier tracking and auditing.

SEBI has categorized algorithms into two types:

White Box Algos: These are fully transparent. Users can see the logic behind them and replicate it.

Black Box Algos: These are proprietary and opaque, mostly used by institutions. These will face stricter rules. Algo providers will need to register as research analysts and keep detailed records of their operations.

Retail investors who create their own trading algorithms and use broker APIs must register these algorithms with the exchange through their broker. These APIs follow the same risk management rules and rate limits as broker's trading platforms, ensuring that a large number of orders won’t compromise market integrity. One of the biggest hurdles in the past was the need to register every strategy and change in strategy to be able to automate trades. With this gone, automated trading becomes more accessible to the public.

Brokers offering APIs (which connect traders to the stock market) must ensure strong security measures, like two-factor authentication. They also need to limit API access to authorized users with unique keys.

Stock exchanges will monitor algo trades after they are executed. If they spot any malfunctioning algos, they will have the authority to stop them immediately using a "kill switch." Exchanges will also ensure that brokers clearly differentiate between algo orders and non-algo orders.

To understand why SEBI is focusing so much on algo trading, let’s take a look at its history in India.

Algo trading started in 2008 when SEBI introduced Direct Market Access (DMA). This allowed institutional investors to place orders directly into exchange systems, skipping brokers. It gave them faster trade execution and better control. Later, exchanges like NSE started offering co-location services, where traders could place their servers close to the exchange’s systems, reducing delays even further.

In the beginning, algo trading was limited to big institutions like mutual funds, hedge funds, and proprietary trading desks. By 2012, SEBI released its first set of guidelines for algo trading, focusing on managing risks and preventing market manipulation.

In recent years, algo trading has moved beyond institutions. Brokers started offering APIs, which allowed tech-savvy retail traders to connect their own algorithms to trading systems. Platforms also emerged, making it easier for retail investors to create and test algo strategies, even without coding skills.

In 2021, SEBI released a consultation paper to address the growing retail interest in algo trading and the risks from unregulated platforms. The paper proposed that all algos be pre-approved by exchanges and placed the responsibility of compliance on brokers. It was one of SEBI’s first major steps to regulate algo trading for retail investors.

By 2022, SEBI issued a circular banning brokers from partnering with unregulated algo platforms. These platforms had become popular for offering pre-built strategies while making misleading claims about guaranteed profits. The circular also prohibited performance claims for algorithms and pushed for greater transparency to stop mis-selling. These actions set the stage for the latest draft circular.

This broader access to algo trading has drawn significant interest from retail investors. However, it has also raised concerns about misuse. Many unregulated platforms offered pre-built strategies with unrealistic promises of high returns. Retail traders, often unaware of the risks, could deploy poorly designed or manipulative algos, leading to losses or disruptions in the market.

While algo trading brings speed and efficiency, it also carries risks. Some algos have been misused for manipulative practices like spoofing, where fake orders are placed to manipulate prices. Poorly designed algos can also malfunction, triggering flash crashes or other market disruptions. These risks highlight why strong oversight is so important—something SEBI has been working to address over the years.

Is debt good or bad?

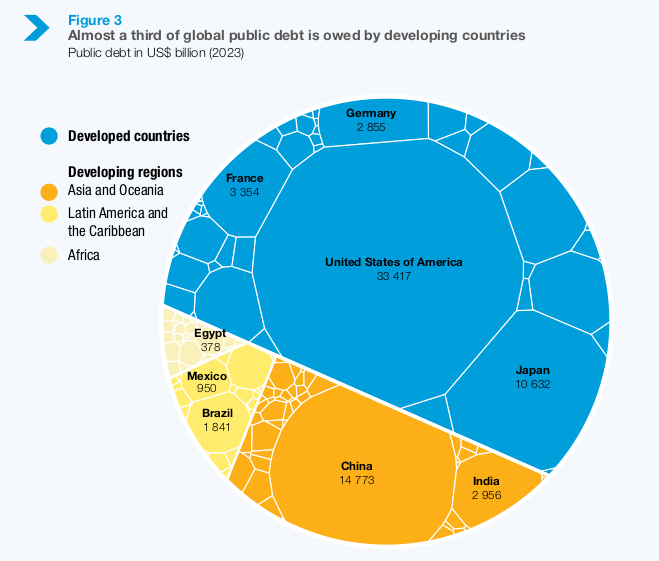

Emerging markets are buried under $29 trillion of debt, with a staggering $850 billion going toward interest payments every year. What’s even more worrying is that public debt in developing countries is growing twice as fast as in developed ones. That’s not just a big number—it’s the kind of figure that makes your calculator flash “error.”

But before we point fingers and label debt as the villain here, let’s take a step back and add some perspective. Because, like most things in life, debt isn’t simply good or bad—it’s all about how it’s used.

Think of debt like coffee. In moderation, it’s great—it keeps you going and helps you get things done. But too much of it? That’s when you end up restless, anxious, and unable to sleep.

The truth is, that debt can be both helpful and harmful. Developed countries like the US and Japan use debt to fund productive investments—things like building infrastructure, boosting innovation, and expanding economic capacity. These investments create growth and make their economies stronger over time.

As long as their economies grow faster than their interest payments, they’re in the clear. Take the US, for example—it has over $33 trillion in debt. Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio? A jaw-dropping 250%. Yet, investors aren’t panicking. Why? Because these economies are large, stable, and have a long history of managing their debt responsibly.

But that’s not the case everywhere.

For emerging economies, debt isn’t just a number on a balance sheet—it’s a heavy burden. Despite being home to nearly 80% of the world’s population, developing countries hold only 30% of global public debt. That imbalance shows just how tough the situation is for these nations.

While debt levels in developing countries may seem small compared to global giants, the burden they carry is disproportionately heavy. Take this: 54 developing countries spend more than 10% of their revenues just on interest payments. More than half of these countries are in Africa.

Here’s a strange but telling comparison: Sri Lanka vs. the US. The US has 330 times more debt than Sri Lanka, yet Sri Lanka is seen as the riskier bet. Why? Because most of Sri Lanka’s debt is used to repay old loans instead of funding new infrastructure or boosting its economy.

The impact of this is devastating. Many developing countries spend more on debt payments than they do on healthcare and education combined. In Africa, for example, the average per-person spend on debt interest is $70, while spending on health is just $39.

That’s not just unsustainable—it’s a human tragedy.

So, why does debt hit developing nations so much harder? A big part of the problem lies in the flawed international financial system.

1. Sky-High Borrowing Costs:

Developing countries pay 2 to 12 times higher interest rates than developed nations. Why? Because they’re seen as risky. Investors demand higher returns for taking on that risk—ironically, from economies that are already struggling.

2. Heavy Reliance on Foreign Creditors:

With limited domestic savings, these countries depend heavily on foreign lenders. But here’s the catch: this debt must be repaid in hard currencies like the US dollar.

The result? Half of developing countries spend at least 6.3% of their export revenues just to service their debt.

3. Private Creditors Don’t Play Fair:

Around 61% of external debt in developing nations is owed to private creditors—banks, hedge funds, and financial institutions. These lenders charge higher interest rates and are notoriously tough when it comes to renegotiating debt. They’re not interested in economic recovery—they’re in it for the money.

So, what’s the way forward?

The UN’s 2024 World of Debt report doesn’t just highlight the problem—it offers solutions. The report lays out a roadmap to finance sustainable development, focusing on three key actions:

Reduce the cost of debt by providing affordable financing options.

Scale up long-term investments, especially in critical areas like infrastructure and climate action.

Fix the global financial system to ensure developing nations have a seat at the decision-making table.

Here’s the thing: debt, when used the right way, can be a powerful tool for growth. But without meaningful reforms, the current system will continue draining resources from where they’re needed most—hospitals, schools, and climate initiatives.

So, the next time someone says, “Debt is bad,” ask them: “Whose debt?” For the US, it’s a flex of economic power. But for countries like Sri Lanka or Nigeria, it’s a full-blown crisis.

And if global leaders don’t step up to fix this imbalance soon, we might be left asking an even scarier question: What happens when the debt finally becomes too much to handle?

Tidbits

IndusInd International Holdings Ltd is set to complete its ₹9,861 crore acquisition of Reliance Capital by January 2025, marking the resolution of one of India’s major IBC cases. The deal includes plans to repay the debt by 2026-27 and strategically list subsidiaries, further strengthening IndusInd’s position in the financial sector.

Apollo Tyres is tackling the challenges of natural rubber shortages and price volatility by shifting to recycled rubber and bio-based materials. The company aims to achieve 40% sustainable sourcing by 2030, reducing its dependence on natural rubber, cutting costs, and aligning with global sustainability goals.

India’s private sector PMI jumped to 60.7 in December 2024, driven by strong growth in services and manufacturing. Employment hit record highs, and easing inflation improved economic outlooks, pointing to strong momentum heading into 2025.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Kashish

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉 Join the discussion on today’s edition here.

Hi,

Referring to point ‘Retail investors can now automate trades.. One of the biggest hurdles in the past was the need to register every strategy and change in strategy to be able to automate trades. With this gone, automated trading becomes more accessible to the public.’

Please refer to the circular page 5 point (c). The requirement of registration of algo by individuals (retail investors) has not gone. It is still there..

Can you please check ..

So we can expect that we can use Kite connect as usual even after these rules come into force