SEBI doesn't like SME IPOs?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

Things might soon change for SME IPOs

SEBI is making big changes in the SME IPO space. The regulator has proposed a set of new rules to tighten how small and medium enterprises (SMEs) list on the stock exchange, raise money, and handle governance after going public. The focus is on stricter rules for the Offer for Sale (OFS) mechanism, better monitoring of how IPO funds are used, and stronger protections for investors.

This isn’t just a small update—it’s SEBI’s way of addressing concerns that the SME platform, which was originally created to help smaller businesses access public markets, is being misused. Promoters are cashing out, funds are being diverted, and retail investors are losing out. SEBI wants to put an end to that.

So, what’s changing, and why now? Let’s break it down.

The SME platform was launched in 2008 to help smaller businesses raise money more easily. Unlike the Main Board, it was designed to be more flexible and less complex. And it worked—over the past couple of years, the SME segment has grown rapidly.

As of October 2024, 745 companies are listed on SME exchanges with a combined market cap of ₹2 lakh crore.

In FY23-24, 196 SME IPOs raised over ₹6,000 crore, and FY24-25 is close behind, with 159 IPOs raising ₹5,700 crore by October.

SME IPOs have come a long way since the COVID-19 years—activity has nearly quadrupled. These aren’t small numbers anymore.

But this rapid growth has also exposed some serious cracks in the system:

Promoters cashing out: The Offer for Sale (OFS) mechanism has turned into a way for promoters to exit rather than raise funds to grow the business.

Misuse of IPO proceeds: Funds meant for expansion are often being funneled into related-party transactions or vague categories like “general corporate purposes.”

Retail investor risks: Small investors are piling into high-risk IPOs, drawn by speculative returns.

Poor liquidity: Once the IPO buzz dies down, many SME stocks become illiquid, leaving investors stuck.

SEBI has noticed and is stepping in to fix these issues. The regulator has proposed several reforms to bring the SME platform closer to the standards of the Main Board.

Let’s take a closer look at SEBI’s key proposals and why they matter:

1. Tightening the rules around Offer for Sale (OFS)

OFS allows existing shareholders—like promoters or early investors—to sell their shares during an IPO. It’s a legitimate way for them to exit, but lately, it’s been overused. Instead of raising fresh funds for companies, a big chunk of IPO money has been going straight to promoters.

Between FY21 and FY23, OFS accounted for:

30% of IPO proceeds in FY21

35% in FY22

40% in FY23

This over-reliance on OFS has hurt the credibility of SME IPOs.

SEBI’s fix:

Cap the OFS portion at 20% of the total issue size or 20% of pre-issue shareholding, whichever is lower.

Limit individual shareholders to selling no more than 20% of their pre-IPO holdings.

These caps ensure most of the funds raised go toward growing the business, not just giving promoters a cash-out option.

2. Stricter monitoring of IPO proceeds

Many SMEs raise funds without a clear plan for how they’ll use the money. SEBI found that a significant chunk of IPO proceeds often vanish into vague categories or get funneled into related-party transactions.

Here’s what SEBI discovered:

50% of SMEs had related-party transactions (RPTs) exceeding ₹10 crore.

20% of SMEs depended on RPTs for more than half their revenue.

SEBI’s fix:

Lower the threshold for mandatory monitoring of IPO proceeds from ₹100 crore to ₹20 crore.

Ban fundraising for “unidentified acquisitions.”

Cap “general corporate purposes” (GCP) allocations at 10% of the issue size (down from 25%).

These changes bring most SME IPOs under tighter scrutiny and ensure that funds are used for measurable, legitimate purposes.

3. Increasing the minimum application size

Right now, the ₹1 lakh minimum application size has attracted a flood of retail investors chasing speculative gains. In FY24, the applicant-to-allottee ratio skyrocketed to 245X.

SEBI’s fix:

Raise the minimum application size to ₹2 lakh or even ₹4 lakh.

This move will reduce speculative participation and keep the SME platform focused on investors who understand and can handle the risks.

4. Extending promoter lock-in periods

Promoters are required to lock in their minimum contributions for three years, but any extra holdings are locked for just one year. Once the lock-ins expire, promoters often sell their shares, destabilizing the stock.

SEBI’s fix:

Extend the lock-in period for minimum contributions to five years.

Phase out excess holdings gradually: 50% after one year, the rest after two years.

This ensures promoters stay invested in the company’s success for longer, aligning their interests with the business.

5. Making the SME platform more liquid

Low trading volumes are a big problem for SME stocks. SEBI found that:

On NSE, 27 companies had no trades between September and October 2024.

On BSE, 63 recently listed companies saw negligible trading activity.

SEBI’s fix:

Increase the minimum number of IPO allottees from 50 to 200.

This broader investor base should improve liquidity, making SME stocks easier to trade.

The SME platform was created to help smaller businesses raise public funds, but it’s become a victim of its own success. Promoters are gaming the system, funds are being misused, and retail investors are getting hurt.

SEBI’s proposals aim to restore trust by:

Ensuring IPO proceeds are used for business growth.

Curbing fund diversion and governance lapses.

Protecting investors from unnecessary risks.

If implemented, these changes could make the SME platform more transparent and reliable—a place where businesses can genuinely grow and investors feel secure. For promoters looking for an easy exit, though, the message is clear: those days are over.

SEBI wants the SME platform to go back to its roots—helping businesses grow, not just offering a shortcut for promoters to cash out.

What does SEBI's recent analysis about royalties tell us?

SEBI recently analyzed royalty payments made by Indian listed companies to their related parties (RPs). These payments are fees that companies pay to their parent firms or affiliates for using intellectual property like trademarks, technology, or brand names. In just one year—FY23—233 companies paid a massive ₹10,779 crore in royalties.

While most payments stayed within the regulatory limit of 5% of turnover, SEBI found that many were disproportionately high when compared to profits. In fact, some companies paid more in royalties than they distributed as dividends to shareholders.

What are royalty payments, anyway?

Think of a company like Nestlé India. It uses the brand name, recipes, and marketing expertise of its Swiss parent company. For this, Nestlé India pays a royalty fee, which is usually a percentage of its sales or profits. The logic is that the parent company’s global expertise helps its Indian subsidiary thrive.

But here’s the problem: if Nestlé India pays too much in royalties, it has less money to reinvest in its business or share as dividends with its Indian shareholders. SEBI’s study found that some companies paid such high royalties to their parent companies that there was little or nothing left for shareholders.

For instance, one in four royalty transactions exceeded 20% of a company’s net profit. In extreme cases, companies paid more in royalties than they earned in profits, leaving no room for shareholders to benefit.

How did we get here?

In the 1970s and 1980s, India’s socialist policies forced foreign multinationals to reduce their stakes in Indian subsidiaries. To protect these local companies, the government capped royalty payments at 5% of domestic sales and 8% of exports.

However, these restrictions were lifted in 2009 to attract foreign investment. What happened next? A sharp spike in royalty payments. Between 2012 and 2019, these payments doubled to over ₹8,300 crore, with just five companies accounting for 80% of the total.

Despite SEBI’s efforts to regulate this—like requiring shareholder approval for royalty payments exceeding 5% of turnover—the issue remains a hot topic.

Key findings from SEBI’s study

SEBI’s analysis uncovered some troubling trends:

Excessive payments:

Many companies spent over 20% of their net profit on royalties.

In some cases, royalty payments exceeded total profits, leaving no money for shareholders.

Source: SEBI

Payments by loss-making companies:

Even companies with losses paid significant royalties. SEBI found 97 instances where these payments exceeded 5% of the company’s absolute losses, amounting to ₹1,355 crore over the study period.

Lack of transparency:

Many companies didn’t disclose why royalties were being paid or how they benefited. Proxy advisory firms flagged these payments for lacking clear justifications.

Fast-growing royalties:

SEBI identified 79 companies that paid royalties every year for a decade. Among these, 18 saw royalty payments grow faster than both turnover and profits, with royalties increasing at a CAGR of 14.6% compared to just 6% for profits.

What does this mean for investors?

For investors, high royalty payments are a big red flag. They hurt profitability, lower shareholder returns, and raise concerns about governance. For parent companies, on the other hand, royalties are a way to monetize their expertise. This creates a tricky balance: how can companies justify these payments while still protecting shareholder interests?

SEBI’s study raises important questions:

Should royalty limits be tied to profits instead of turnover?

Should companies provide detailed disclosures about why these payments are made and how they benefit the business?

Should royalty agreements come with expiry dates to prevent perpetual payouts?

Is the Indian economy doing well?

India's economy is at an intriguing crossroads. On the surface, the numbers tell a success story—steady GDP growth, strong services exports, and bustling infrastructure projects. But dig a little deeper, and you’ll find a tale of contrasts. Some sectors are racing ahead, while others are struggling to keep pace. Let’s take a closer look at what’s thriving, what’s faltering, and how the landscape is shifting.

Consumption: The backbone of India’s economy

Consumption drives nearly 60% of India’s GDP, making it the engine of economic growth. But right now, it’s as uneven as the economy itself.

Urban consumption

Urban India has been leading the charge in consumption recovery, particularly among high-income households. The festive season of late 2024 brought a temporary surge in spending on luxury cars, premium electronics, and designer goods. But there’s another side to this story. Inflation and rising food prices are putting a strain on middle-income households, and the impact is starting to show.

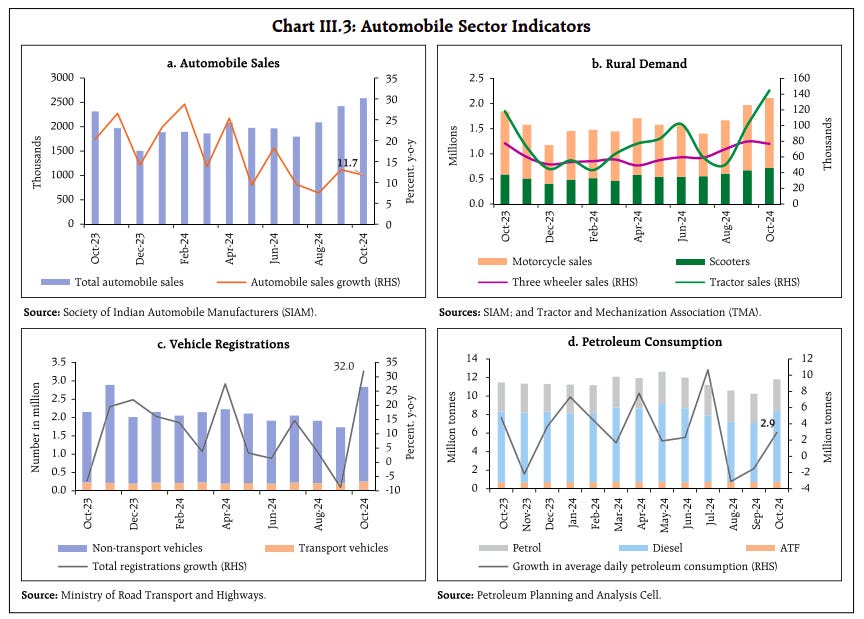

Automobiles: Luxury car sales are booming, but mid-range vehicles saw only a modest 3% year-on-year growth in October 2024—a clear sign of sluggish demand from middle-class buyers.

Source: RBI FMCG: Demand for everyday goods has softened. Value growth is outpacing volume growth, meaning higher prices—not increased consumption—are driving sales.

Services: Travel, dining, and leisure spending remain strong, fueled by pent-up demand. Hotel occupancy rates hit 72% during Diwali, the highest since 2019.

Urban consumption paints a polarized picture: the wealthy continue to spend freely, while middle-income households are feeling the pinch.

Rural consumption

Rural India, home to 65% of the population, is starting to show signs of life, but the recovery remains delicate. A favorable monsoon has boosted agricultural incomes, and government investments in rural infrastructure are beginning to have an impact. Even so, progress is cautious:

Two-wheelers: Sales rose 14% year-on-year in October 2024 but are still below pre-pandemic levels.

FMCG: Rural volumes have outpaced urban growth for the first time in three years, but the improvement comes from a low base.

Discretionary spending: Non-essential purchases remain muted, reflecting lingering uncertainty in rural areas.

India’s consumption story feels unbalanced. Urban aspirations and rural necessities are holding things together, but the middle ground—the core of economic activity—is struggling. Middle-income households, which should be driving growth, are under significant pressure from inflation and uneven job creation.

For sustained economic growth, this imbalance needs attention. Structural fixes—like creating more equitable job opportunities and addressing inflation—are critical to unlocking the full potential of India’s consumption engine.

Demand: The split between private and corporate

When it comes to demand, the picture is split—private consumption is driving recovery, but corporate investment remains hesitant.

Private demand

Private consumption, especially in services, is holding strong. Domestic tourism has made a comeback, nearing pre-pandemic levels, and e-commerce platforms saw record sales during the festive season, fueled by urban millennials and Gen Z shoppers. But it’s not all smooth sailing. Inflation is biting into purchasing power, and rural demand, though recovering, still has a long way to go.

Corporate demand

Corporate India tells a different story. While balance sheets are healthier than ever—thanks to years of debt reduction—demand from businesses remains muted.

Muted Earnings: Key sectors like FMCG and automobiles reported only single-digit revenue growth in Q2 FY25, with rising input costs squeezing margins. Even sectors like cement and steel, which usually benefit from infrastructure spending, saw lackluster growth due to weak downstream demand.

Capacity Utilization: Manufacturing capacity utilization is at 75%, still shy of the 80-85% needed to trigger fresh investments.

Private Capex: Despite government policies like the PLI scheme, large-scale private investments are mostly limited to supported sectors like electronics and renewables.

This mismatch between strong private consumption and cautious corporate spending highlights an imbalance that could weigh on long-term growth.

Exports: A dual reality

India’s export performance is a mix of highs and lows, with resilient services exports overshadowing weak merchandise trade.

Merchandise exports

Goods exports showed modest growth in October 2024, led by engineering goods and textiles. However, broader challenges persist:

Gems and Jewelry: Traditionally a strong performer, this sector is struggling with weak global demand and regulatory hurdles in key markets.

Petroleum Exports: Volatility in global oil prices has slowed export growth, dragging down overall performance.

Export Composition: A reliance on low-value-added goods leaves India vulnerable to global shocks and trade changes.

Services exports

On the flip side, services exports are thriving. IT and digital services grew over 11% in H1 FY25, driven by demand for cloud computing, AI, and cybersecurity. This resilience is a stabilizing force for the economy, even as merchandise trade falters.

Corporate India: Strong, yet hesitant

Indian companies are in solid financial shape, with low debt and stable profit margins. But that hasn’t translated into aggressive investment.

Earnings Under Pressure: Rising costs and inflation are hitting profitability in domestic-focused sectors like FMCG and automobiles. Export-driven sectors like IT and pharma, however, are performing better.

Source: RBI Selective Investments: Corporate investments remain concentrated in government-supported sectors like renewables and electronics, leaving the broader industrial landscape hesitant.

What’s working?

Services Exports: IT and digital transformation services are driving growth.

Government Spending: Investments in infrastructure—roads, railways, and green energy—are providing a solid boost.

Digital Economy: Innovations like UPI are reshaping consumption and access across income groups.

Banking Stability: With low NPAs and ample liquidity, banks are well-positioned to support growth.

What’s not working?

Muted Corporate Earnings: Rising costs and inflation are squeezing margins.

Private Capex: Large-scale investments are still limited despite policy incentives.

Rural Recovery: While improving, rural demand remains fragile.

Export Composition: Over-reliance on low-value goods makes the economy vulnerable.

Emerging trends

Premiumization: Urban consumers are shifting toward higher-value goods.

Manufacturing Push: Growth in electronics and renewables is promising, but broader industrial expansion is needed.

Green Transition: Investments in renewable energy are accelerating, positioning India as a global leader in the green economy.

Conclusion

India’s economy is a paradox—resilient yet vulnerable, dynamic yet cautious. Services exports, government spending, and digital innovation are creating opportunities, but challenges, like muted corporate earnings, inflation, and rural fragility, remain. The road ahead requires balancing these strengths and vulnerabilities to unlock India’s full potential.

The big question is: Can India bridge these gaps and solidify its position as a global economic powerhouse? The answer will define its future trajectory.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉 Join the discussion on today’s edition here.