Rock-solid quarter for the cement sector

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

How did the cement companies perform this quarter?

The global insurance industry might have a problem

How did the cement companies perform this quarter?

The 3 largest cement companies of India just reported their Q2 FY26 results.

Cement is one of those industries that says a lot about the economy. And the 3 companies — UltraTech (Birla Group’s cement arm), Ambuja (owned by the Adani Group), and Shree Cements represent over 45% of India’s cement capacity combined. Their strategies offer an interesting lens into the state of India’s infrastructure, housing, and, to some extent, even industry.

We’ve written before about how India’s cement industry works — we highly recommend reading any of them (here and here) to get a sense of the main drivers of the industry.

The Numbers

See, Q2 is historically softer than Q1 due to monsoons disrupting construction activity across much of India. But even then, compared to the same time last year, Q2 this year has been an improvement.

Birla’s UltraTech reported consolidated revenue of ₹19,371 crore, up 21% year-on-year, with unit volumes growing 7%. EBITDA margins grew from ~14% to 17%. Net profit came in at ₹1,238 crore, up 75% from ₹708 crore last year, but 45% down from last quarter.

Even with seasonal cycles, such a fall is a little unexpected. But the reason for this decline is one-off costs: like higher spends on maintenance, advertising, and employee benefits.

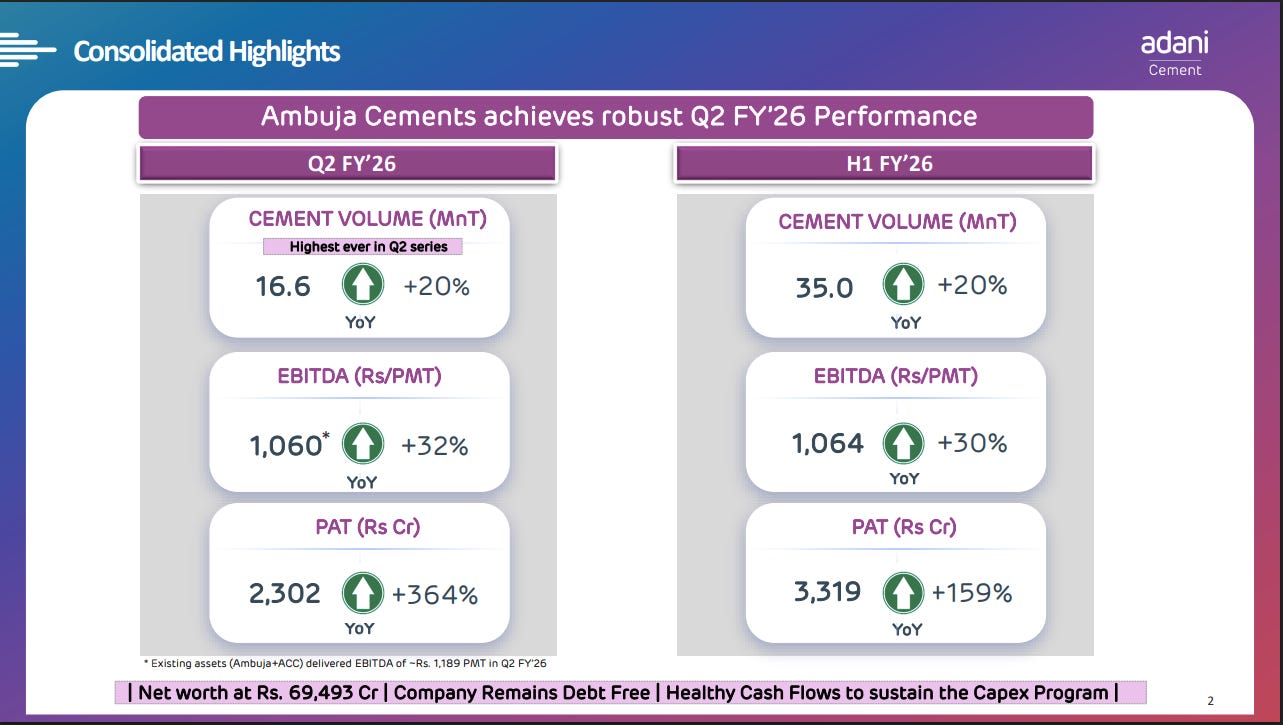

Adani (Ambuja) Cements had a stellar Q2. It posted revenue of ₹9,174 crore, up 21% year-on-year. Volumes surged 20% to 16.6 million tonnes—the best Q2 ever for the company. This lifted their all-India market share to 16.6%, which is ~1 percentage point higher than last year.

Ambuja’s EBITDA margin increased from 14.2% last year to 19.2%. The EBITDA per ton — a key metric in cement — improved to ~₹1,060, up 32% year-on-year.

Shree Cement reported revenue of ₹4,761 crore, up 17% y-o-y. Volumes grew more modestly at ~7% to 7.9 million tonnes. Unlike its peers, Shree emphasized pricing and product mix over sheer volume growth, and this strategy paid off: EBITDA surged 45% to ₹1,153 crore, implying an EBITDA margin of 24.2%. EBITDA per tonne jumped 43% to about ₹1,105—the highest among the three.

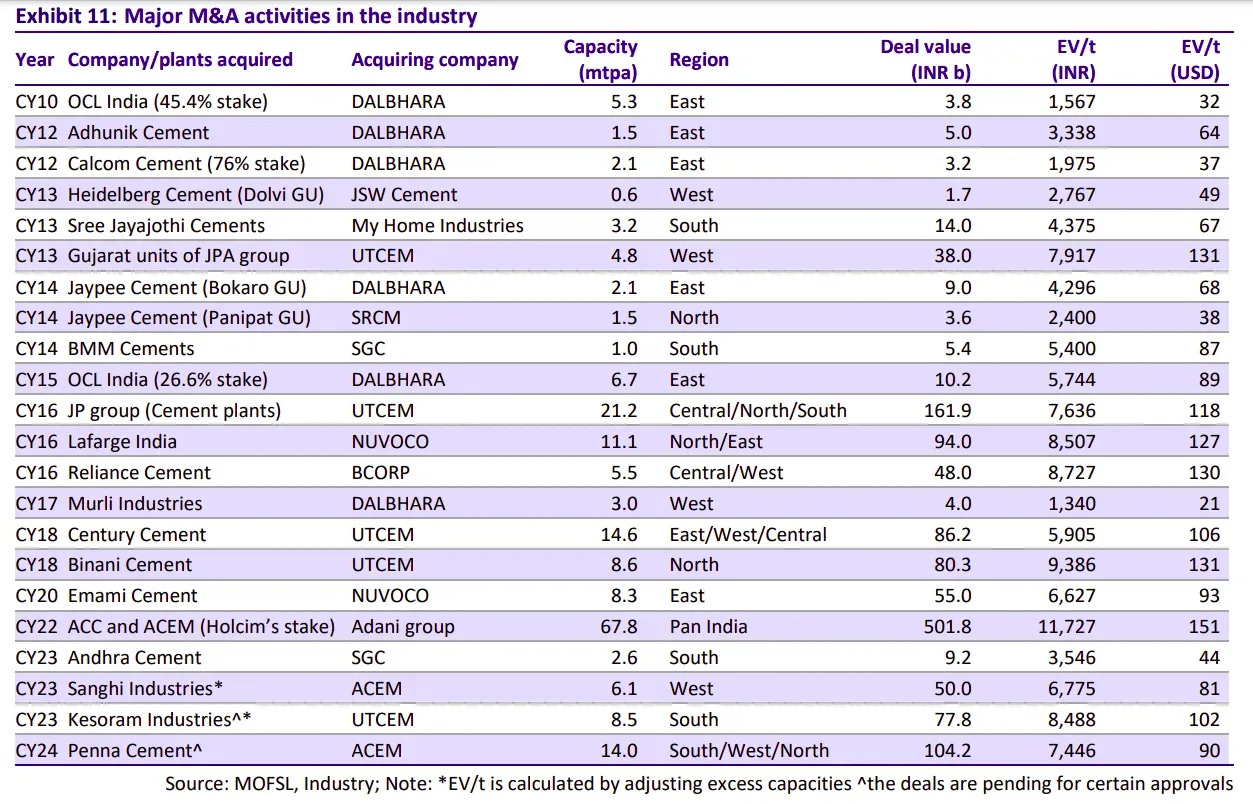

The entire industry is going through a massive wave of consolidation. UltraTech acquired Kesoram’s clinker assets and took a majority stake in India Cements. Ambuja has bought ACC, Sanghi, and stakes in Penna Cement and Orient Cement. Both of them are in the process of fully integrating these acquisitions into their business.

Aggressive cost reduction

If there’s one theme that dominates Q2 results, it’s cost optimization. Cement prices have been under pressure all year. The industry is notoriously cyclical, with limited pricing power except in pockets. So when margins improve despite flat or slightly declining prices, it means companies squeeze the most out of what they spend — especially since cement is a capital-intensive sector with huge fixed costs.

Three cost drivers dominate cement economics: fuel and power, logistics, and raw materials to make cement — like limestone and gypsum.

Fuel and power costs

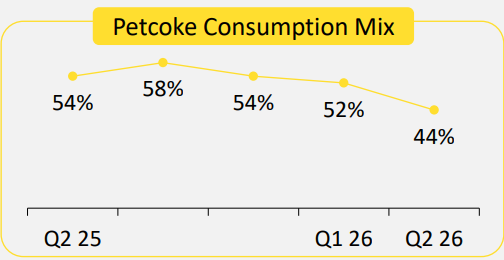

Take fuel, for instance. Sequentially, from the last quarter, fuel costs have increased for everyone. This is because pet-coke, the primary fuel used in cement kilns, became more expensive globally. And pet-coke inflation might continue further in the year.

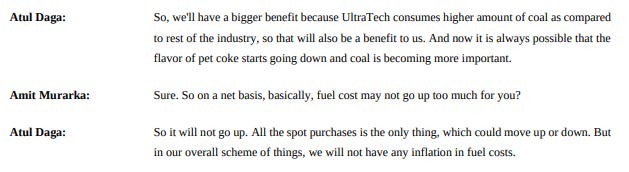

Different companies react to it differently. UltraTech uses a fairly equal mix of coal and pet coke in its kilns. Their high use of coal compared to peers has helped them keep fuel costs 6% lower than the same time last year.

Ambuja, on the other hand, cut kiln fuel costs from ₹1.65 per 1,000 kilo-calories to ₹1.60 — primarily due to the use of alternative fuels. They’re also using the Adani Group’s own coal mining expertise to secure captive coal.

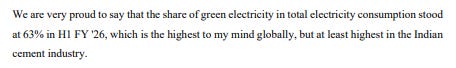

To help offset these fuel costs, these companies rely a lot on generating their own electricity. Using the Adani Group’s synergies, Ambuja has increased its share of green power in the total energy mix by 14.3 percentage points to 32.9%. UltraTech’s green power share is at 42%. Shree Cements, which operates its own thermal power plants and has invested heavily in waste-heat recovery, meets 63% of its power requirements from green energy—the highest share in the industry.

Logistics costs

Logistics optimization also matters enormously. Cement is a bulky, low value-to-weight product, so its freight costs are significant. And cement producers constantly try to optimize for it.

This quarter, both sequentially and on a y-o-y basis, logistics costs have improved.

Ambuja reduced its average transport distance by 2 km this quarter, with logistics cost per tonne falling ~7% year-on-year. UltraTech’s logistics costs have also declined 6% from last year. Shree is expanding rail’s share of transport from 11% to 20%, which can lead to additional savings. The company is constructing multiple new railway sidings to facilitate this.

Clinkerisation

Then, there’s optimising costs through clinkerisation.

Cement isn’t made directly from limestone, but an intermediate product called clinker, which is created by heating limestone to a high degree in massive rotary kilns. How much clinker goes into cement makes an impact on cement quality. So companies also invest significantly in making clinker — especially since having your own clinker capacity provides a hedge against rising raw material costs, too.

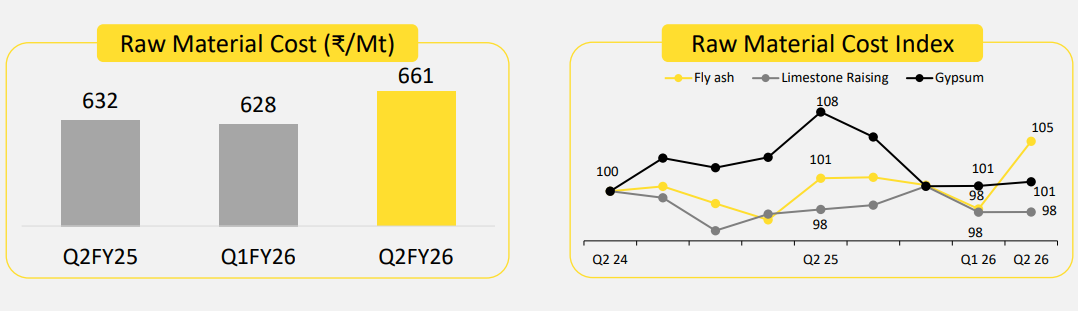

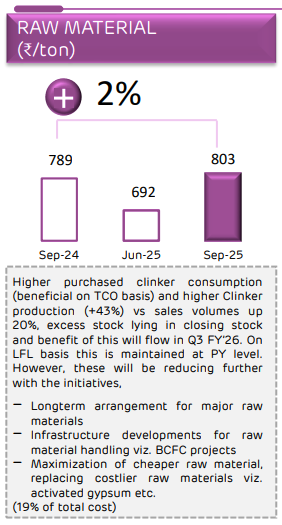

And you can see that play out this quarter, as raw material costs have spiked for all players now.

But each of them is heavily focused on improving their clinker capacity, and how quickly they can convert clinker into cement.

Ambuja currently has ~65 MTPA clinker capacity for ~107 MTPA cement capacity, and plans to raise clinker capacity to 96 MTPA by FY28. Similarly, Shree Cement has just commissioned a new 3.65 MTPA clinker line in Rajasthan. Along with plans to expand cement capacity over the next 2-3 years, UltraTech is also prioritizing expanding clinker capacity by 148 million tons.

Debottlenecking

Lastly, there’s debottlenecking. This is nothing but a fancy term for small, incremental upgrades to existing plants: like widening conveyors, upgrading kiln burners, and so on. Unlike building new plants, debottlenecking is a cheap and fast way to reduce costs without incurring too much capex.

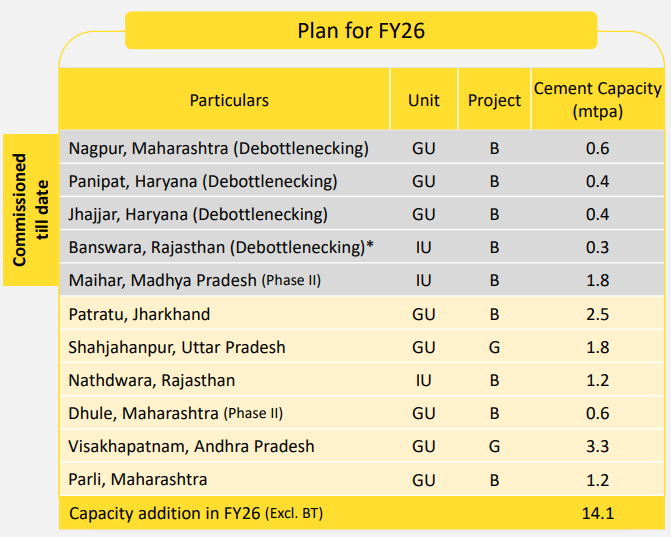

Take a look at UltraTech, for instance. In its FY26 plan, it is adding ~1.7 MTPA of capacity just through debottlenecking — at a fraction of the cost of new kilns.

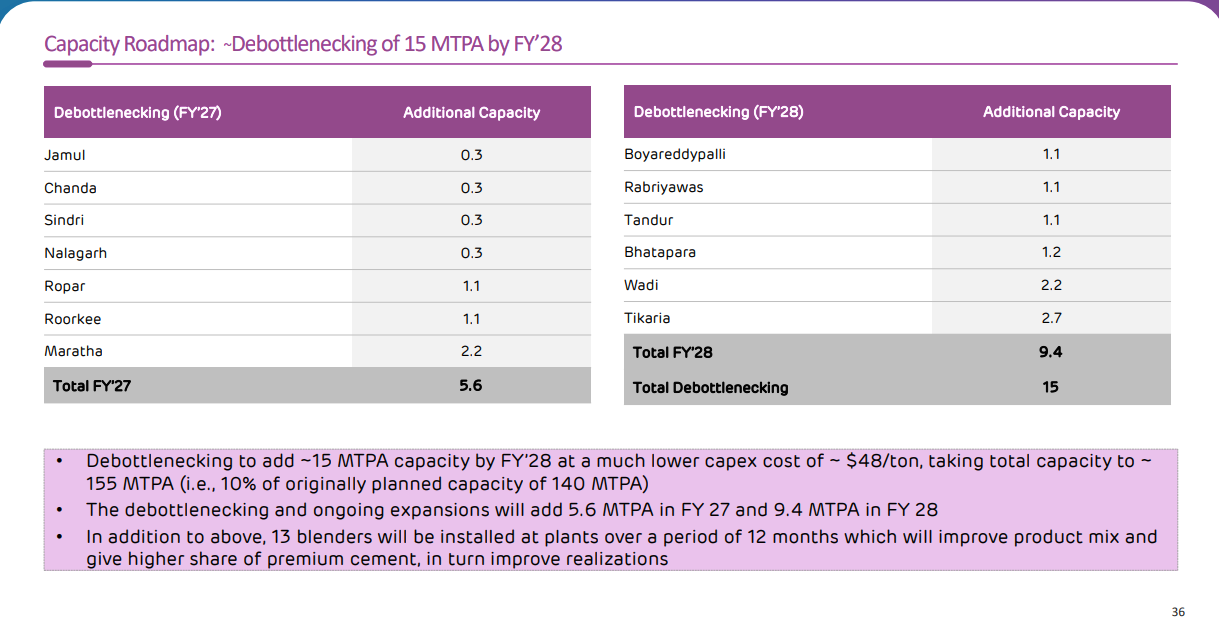

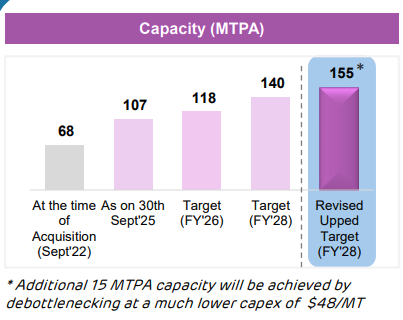

For Ambuja, the efficiency opportunity is even larger through synergies with the larger Adani Group. By FY28, through debottlenecking, it plans to add 15 MTPA of capacity at much lower capex.

Shree Cement is also undertaking a debottlenecking program to add 0.5 MTPA of additional output.

Ambitious expansions

Now, let’s move on to the sales side, and first see where the business is coming from.

Geography and sector mix

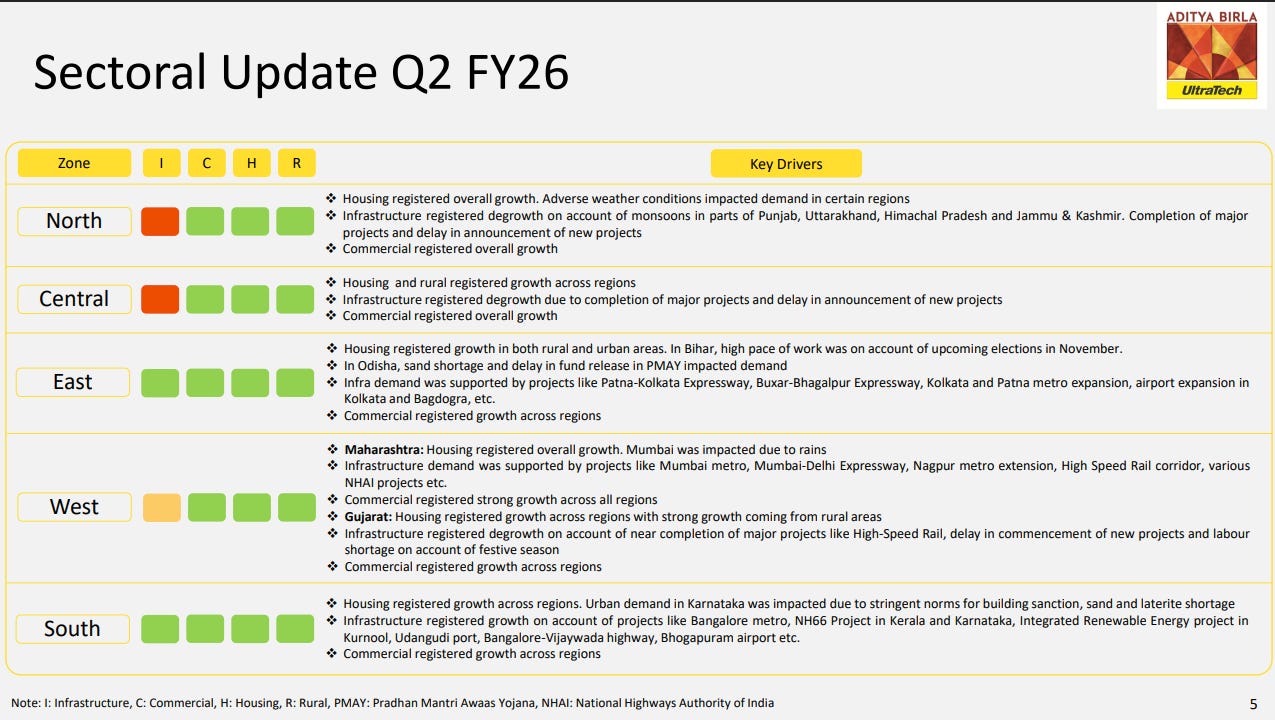

Geography matters enormously in cement. Since cement’s freight costs make it uneconomical to transport cement over long distances, regional market shares look quite different from national shares. Shree Cements dominates Rajasthan, while Gujarat is Ambuja’s territory. In Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, regional players like Dalmia Bharat and Ramco are strong. The consolidation wave partly reflects bigger players wanting to expand their footprint by acquiring smaller ones.

That’s how UltraTech and Ambuja built a sizable pan-India presence. On the other hand, though, Shree Cement finds itself mostly concentrated in north India, where heavy monsoon rains hit harder and competition has also intensified. They find it harder to hedge weaker performance in North India against stronger performance elsewhere.

Within sectors, housing and infrastructure are the growth engines. All three players have highlighted government schemes for affordable housing as a major tailwind. And this tailwind isn’t just restricted to urban areas — rural seems to be just as important a focus. For UltraTech, their rural markets have grown 13%; here’s what they say about rural housing:

Infrastructure has taken a bit of a hit this quarter, owing to monsoons and the completion of existing projects. But, it is well expected to rebound next quarter, with multiple mega-projects in India underway.

And in anticipation of growing infra and housing needs, cement companies are doubling down on expanding capacity aggressively. All three companies are in the middle of massive capacity expansion cycles. UltraTech will be investing at least ₹10,000 crore each year until FY28 to bring up total capacity to 240.8 MTPA. Shree Cement is targeting about 80 MTPA by FY28, up from ~50 MTPA now. Ambuja, while at 107 MTPA now, wants to get to 155 MTPA by FY28.

A premiumization trend?

A common talking point in the cement results was that of premiumization. At Markets, we’ve covered premiumization multiple times — as recently as 2 days ago.

All three cement firms are pushing higher-margin products, like specialty cements and ready-mix concrete (RMC). A higher share of these premium products in the mix has helped realizations to some degree. Shree grew the premium share to 21% from 15% a year ago. Ambuja’s premium volumes, which are growing 28% y-o-y, formed 35% of trade sales.

That being said, cement still largely remains a commodity. The pricing power from premiumization seems fairly limited.

The impact of GST 2.0

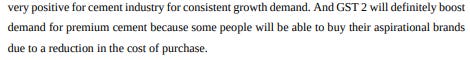

A huge talking point this quarter was how GST would affect the cement business. The government cut GST on cement from 28% to 18%. And the industry is very happy about this.

All three firms will fully pass on the entire 10 percentage point reduction to end customers.

But, while they get none of the benefits in the short-term, the long-term benefits are much more powerful. Lower GST could stimulate demand in various consumer sectors, like affordable housing. All the players also expect that lower GST will make it far easier to sell more of their premium products.

The GST reform also removed the Clean Energy Cess of ₹400/ton on coal, directly lowering fuel costs. Over time, this structural shift is expected to enhance EBITDA per ton.

Conclusion

India’s cement industry is continuing to expand aggressively. All the major players are buoyed by India’s increased spending on mega infrastructure and housing projects all over India. And in turn, they are all fueling money into expanding capacity ferociously.

However, cement is also a business where cost spikes — especially in raw materials and fuel — are all too common. And going forward, these will still be risks that require fighting another battle to reduce costs wherever possible. At the same time, the cement industry itself is in a turbulent situation, as bigger companies try to swallow up and integrate smaller ones.

These are very interesting times for one of the most important industries in India.

The global insurance industry might have a problem

In an ideal world, life insurance companies would all be terribly boring. For a long time, they were.

They operated on a simple promise: collect small premiums, place them in safe securities like government bonds, and pay out claims decades later when they came due. This simplicity allowed them to stand firm during the 2008 financial crisis, when banks collapsed like dominoes. Back then, AIG was the only insurer that saw serious problems — and was generally considered an exception.

But the crisis changed the industry.

In the “easy money” era that followed the crisis, the safest investments — government bonds — yielded little. At the same time, insurers’ promises to their policyholders were already locked in, and they simply didn’t have the option to reduce what they owed. A German life insurer, for instance, might have promised a retiree 4% returns in 1995. But by 2015, they would actually have to pay to hold German government bonds, as negative interest rates took hold.

In much of the developed world, insurance companies had to choose: lose money on every policy, or abandon everything that made them safe businesses and go for higher returns. They chose the latter.

While this helped the industry navigate a particularly treacherous time, it has also allowed massive risks to build up within the system. The last financial crisis, it appears, might have sown the seeds for the next one. And a recent paper from the Bank for International Settlements lays those risks out in devastating detail.

Let’s dive in.

The Transformation

In our new, post-GFC financial environment, the life insurance industry has turned riskier, more speculative, and more complex than ever before. To be fair, it has also become more profitable. But if things go wrong (especially when you least expect it), the business will be caught off guard.

This new vulnerability is the outcome of many major shifts.

Changing investment landscape

The first change came directly from the easy money era that followed the crisis.

Will rates at all-time lows, government bonds barely yielded any interest. To this point, insurers had traditionally sold policies that yielded a fixed return. But as the interest dried up, these became hard to service. Insurers would eventually respond by shifting to more flexible securities. Meanwhile, to meet their obligations, they began looking for assets that brought higher returns.

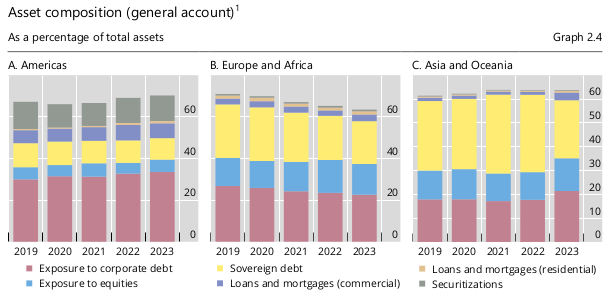

In the US, where this shift was the most prominent, as much as 18% of life insurers’ assets were in these structured securities. In Europe and Asia, insurers loaded up on foreign bonds (like US Treasuries), taking on new risks that came with fluctuating forex rates. Japanese life insurers alone, for instance, hold $530 billion in foreign bonds, most of which are American.

Private equity

The worst of this risk can be seen in one cohort of insurers: those linked to private equity (or PE).

Post-GFC, insurance companies were desperate for higher returns and new capital. To PE firms like Apollo or Blackstone, this was an opportunity. Since 2010, PE has increased its investment in insurance sevenfold, well outpacing other segments.

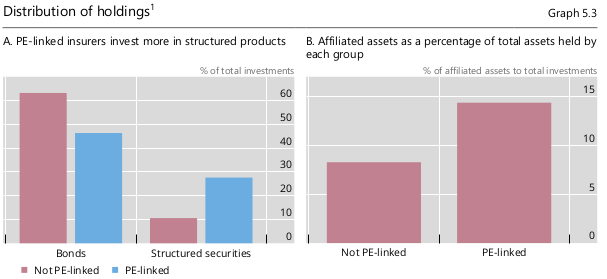

This injected fresh money into the industry, sending valuations higher. But that has come with risks. PE-linked insurers are driven to riskier bets — they’re twice as likely to buy structured securities, including the mortgage-backed securities that were at the centre of the 2008 crisis. Worse still is the sheer conflict of interest within these companies. PE firms don’t just own insurance companies; they create the investments those companies buy. As BIS found, PE-linked firms are much more likely to buy “affiliated assets” than other insurers.

The echoes of 2008 don’t stop there. In many countries, an insurer’s capital requirements depend on the credit rating of what they invest in. Only, as insurance companies take to investing in more obscure instruments, getting accurate credit ratings has become harder. Almost a quarter of the investments PE-linked insurers make aren’t rated publicly, but rely on secretive “private letters” — given out by small agencies. A lot of the real risk, then, is hidden from everyone.

Reinsurance

Perhaps the most audacious change comes in how readily insurers have ceded away their risk to re-insurers.

In a way, reinsurance has emerged as a means of regulatory arbitrage. In much of the world, insurance is regulated heavily, with strict rules around how much capital a company must have and the investments it’s allowed to make. But insurers have discovered that they can lighten that burden by buying insurance on their insurance. This takes risk off their books, freeing up their capital to do more.

Only, it isn’t clear if any of that risk actually goes away. Many of these reinsurers are based in lax, tax-haven jurisdictions like Bermuda or the Cayman Islands. Insurers are entering into increasingly opaque, complex relationships with them — think lots of shell entities — bringing asset managers, sovereign wealth funds and others into the mix. These arrangements have a distinctly pro-cyclical nature: they’re doing well while things look good, but could turn into junk when a shock arrives.

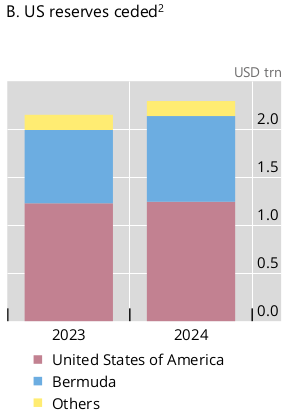

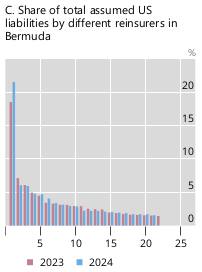

In 2024, for instance, American life insurers had ceded away $2.1 trillion in liabilities — four times as much as they had in 2017. 40% of this risk had been pushed offshore, often to risky countries. In fact, they’ve pushed off $1 trillion in liabilities to reinsurers in Bermuda alone.

There’s a possibility that, in effect, companies aren’t reducing their risk, but are simply hiding it away from the eyes of regulators.

The risks are massive

Now, the fact that risks exist isn’t the problem. Risk, and the ability to manage it, is a feature of financial systems. The problem lies in the size and immediacy of the risks.

BIS looks at two measures of risk.

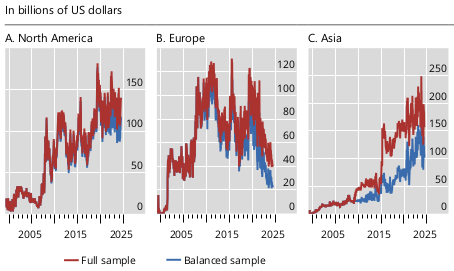

The first, SRISK, looks at what insurers themselves stand to lose in case things go wrong — and the amount of money it would take to bail them out. This stands at ~$400 billion globally, which is large, but an entire order of magnitude lower than that for banks. This has, however, been rising rapidly. The SRISK of insurers in North America and Asia has doubled over the last decade.

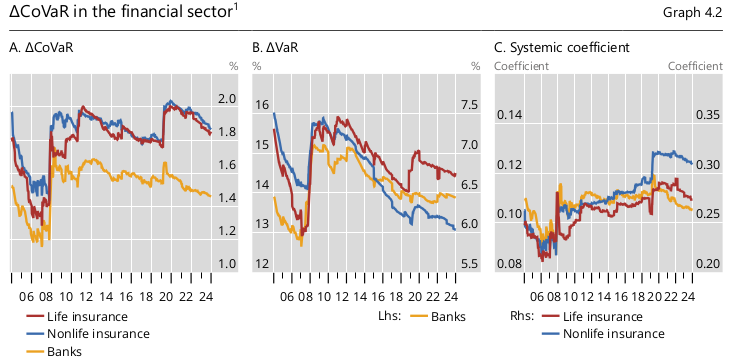

The real danger, however, lies in the second measure of risk: ΔCoVaR. This measures how much a shock to the insurance industry could hurt the broader financial system. Since the GFC, the insurance industry has become increasingly interwoven with the rest of the financial system.

These linkages come in all shapes and forms. Increasingly, insurance firms are owned by the same entities as the rest of the sector; they’re investing in the same assets, and are going for the same hedging mechanisms. A failure, then, could send ripples much further across the financial system. The “systemic coefficient” — the exposure of the financial sector to the insurance industry — is now well higher than it was during the GFC.

Think of how ruinous the catastrophic bets of AIG were to the wider financial system, back in 2008. If such an event occurs today, it’ll be felt far more dearly than then.

The time bomb

If BIS is to be believed, the global insurance industry is sitting on a time bomb with many fuses.

The first is that an insurer might come under a liquidity crunch. In recent years, insurers have increased their short-term borrowing, which tends to dry up at exactly the wrong time. They’ve also changed the structure of their insurance products — American insurers, for instance, have increasingly made it easier for policyholders to “surrender” their policies, and ask for cash in return. This opens the door for moments where insurers suddenly find themselves having to pay out a lot of money.

That’s what happened with Italy’s Eurovita in 2023. Until 2021, the company seemed reasonably healthy, with its solvency ratio at 230%. But as interest rates rose in 2022, its portfolio of fixed interest bonds started losing value. Soon, its solvency ratio had fallen to ~130%. Meanwhile, its own policyholders saw higher-interest instruments that were more attractive and started redeeming their policies. The company had to sell its investments at a loss just to get cash to meet those redemptions. As the pressure increased, it threatened to spark a system-wide panic, forcing regulators to step in and freeze all redemptions.

Simultaneously, insurers are making riskier, less liquid investments — which become hard to sell exactly when you need to do so.

Currency movements, meanwhile, can hurt an insurer’s solvency, as we’ve written about recently. In May 2025, Trump’s tariff announcements sent Taiwan’s currency up 8% against the dollar in a week. The country’s life insurers suddenly saw their unhedged U.S. investments tank in value, losing billions.

Insurers usually hedge themselves against risks of this sort. For instance, to protect against interest rate changes, insurers usually buy “interest rate swaps”. Similarly, to protect themselves against sudden changes in forex rates, they’re also buying “currency derivatives”. In fact, between 2019-2023, the median value of insurers’ derivative contracts went from 25% of their assets to 35%.

These derivatives are basically side bets on where interest or forex rates may go, and they help protect against the naked solvency risk sitting on many insurers’ balance sheets. But they also create a new sort of liquidity risk. Perhaps, they’re the second possible “fuse” that could take down the system. If those bets sour and rates move in the opposite direction, insurers might suddenly be hit by a margin call and must put up more cash. In 2022, for instance, American insurers had to put up an estimated $15 billion — a tenth of their total cash reserves — to meet margin calls.

And the industry’s practices are creating singular points of failure.

Consider this, for instance: 20% of all the liabilities reinsured by American insurers sit with a single company in Bermuda. It’s hard to imagine how it can handle all that risk — given that Bermuda’s insurance industry is 150 times as big as its GDP.

There are many other such points of failure — many of which come from PE. These link the industry’s fortunes together. Any of these could trigger industry-wide distress.

And finally, as the insurance industry grows more connected to the rest of the financial sector, it creates new pathways for a general financial crisis. For instance, insurers are the largest holders of corporate bonds in many markets. If they’re forced to sell their assets in a hurry, borrowing costs could spike across the economy. The flow of credit would freeze, and an insurance problem could suddenly become everyone’s problem.

Is a reckoning inevitable?

In the years after 2008, the global life insurance industry was forced to adapt to a decade of new rules and near-zero rates. And by most accounts, it was successful. Profitability recovered, solvency improved, and the sector carried on as usual. But that period is now unwinding, and with it, new worries have materialised.

This paper draws out that nightmare scenario: one fine day, a seemingly small change suddenly triggers something ugly. Margin calls and redemptions erupt. Insurers suddenly find themselves bleeding cash. They’re forced to dump their investments in the market, and in those few days, it suddenly turns out that many of those were completely hollow. Losses cascade. One insurer is hit by a solvency crisis, and then another, and before you know it, the global economy is in crisis.

But this isn’t destined to be, and can be avoided. The BIS’s own recommendations are not rocket science — more transparency, better governance, smarter risk management. But that’s the point. They can return the industry to its boring role as the economy’s shock absorber, rather than the source of a crisis.

Tidbits

The CEO of Birla Opus Paints under Grasim Industries, Rakshit Hargave, has resigned and is joining Britannia as the CEO.

Source: Livemint

Hindalco Industries expects a $550–650 million cash flow impact following a fire at Novelis’ Oswego plant in the US, which disrupted production in September. The company said insurance will cover 70–80% of the losses, and operations are expected to restart by December.

Source: Businessline

India’s services sector growth eased to a five-month low in October, with the HSBC India Services PMI slipping to 58.9 from 60.9 in September.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Pranav

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉