Recap: Trade wars, bullish private sector, past, present and future of the Indian economy and more

This is the eighth weekly brief. We publish a new episode every day to help you understand the biggest stories in the Indian markets. But we understand that you may be busy and don't have the time to listen to the daily episodes. So don't worry; we've got you covered.

Every week, we'll publish a new episode simplifying the biggest stories of the week so that you can still look smart in front of your friends.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts and video on YouTube.

If you have already listened to daily episodes of The Daily Brief, do check out our other shows, The Big Perspective and Please help me understand!

In this week's episode, we look at these stories:

Trade wars

Private sector is hot for India again

The past present and future of the Indian economy

Is India open for business?

Will Zomato pull another Blinkit?

Trade wars

India recently launched an anti-dumping investigation into imports of steel products from Vietnam. The concern is that Vietnam has been dumping cheap steel into the Indian market, which has alarmed domestic players like JSW Steel and ArcelorMittal Nippon Steel. These companies are worried that these low-cost imports are hurting their business by making it difficult to compete, as they can't match the prices set by Vietnamese steel makers.

Source: CRISIL

Specifically, India’s investigation targets Hot Rolled Coil (HRC) steel imports from Vietnam. HRC steel is widely used in manufacturing car parts, building structures, and machinery. On the surface, this might seem like a step in the right direction, but the reality is that India doesn't import much of its steel from Vietnam. The bigger issue is China.

China is a major supplier of steel to India, as it is to many other countries. According to S&P Global, in July alone, Chinese steel was expected to make up 73% of India's total steel imports.

Source: S&P Global

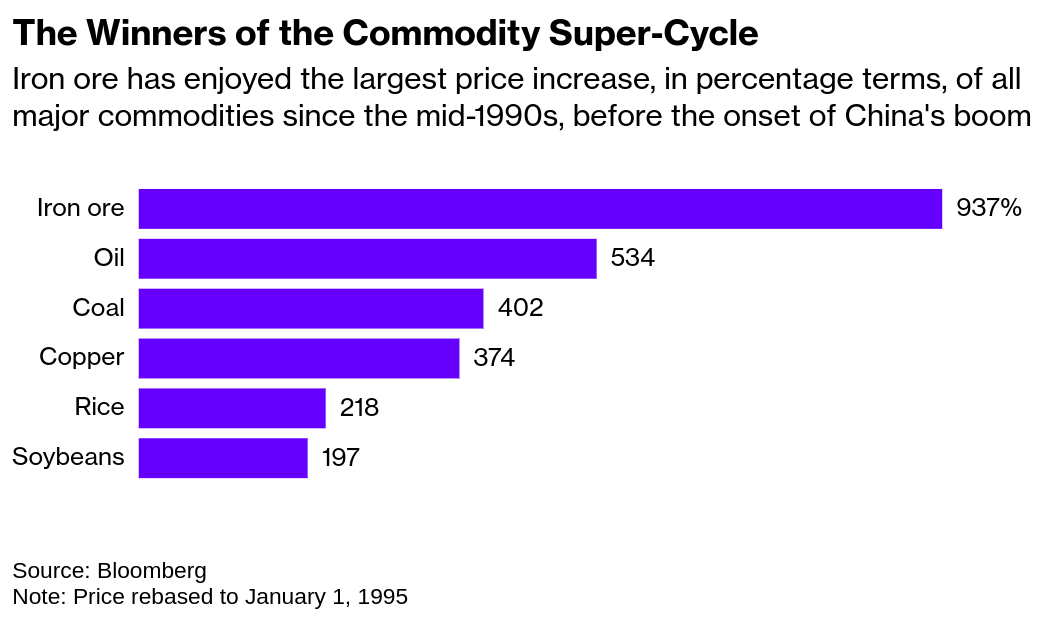

Over the past few decades, China transformed into an economic powerhouse largely due to massive government investments in infrastructure. China poured enormous sums into building highways, railways, power plants, heavy industries, and vast urban housing projects. This rapid industrialization turned China into an export giant and the "world's factory." To fuel this growth, China required vast amounts of steel, which in turn drove up global iron ore prices over the last 25 years.

Source: Bloomberg

However, the situation in China is shifting. The Chinese economy is no longer expanding at the breakneck pace it once did, which means the country doesn't need as much steel as before. This has led to excess steel production, and China now needs to find ways to offload this surplus.

The world’s largest steel producer, based in China, has even described the current conditions in China's steel sector as a "harsh winter," one that will be "longer, colder, and more difficult to endure than expected." This is deeply concerning. So, where does all this extra steel go? As we mentioned earlier, they dump it in other countries.

The problem with dumping is that it can lead to global dependency on a single country. This could give China even more power in global trade, which poses significant risks. Why? Because China’s dominance in global trade means it could start using its power to pressure other countries. For instance, if China decided to stop exporting certain materials or products, countries that heavily rely on these imports would face serious challenges. Additionally, because China can produce more than it needs, it can sell products at low prices, potentially driving domestic companies out of business because they can’t compete.

We’re already seeing the impact of Chinese steel imports on prices. In mid-July, Chinese Cold Rolled Coil (CRC), used in making home appliances, car body panels, and furniture, was sold to Indian importers at $610 per metric ton. Even after adding a 7.5% import tax, Chinese steel was still over ₹4,000 per metric ton cheaper than the same type of steel made in India.

It’s not just India feeling the pressure; other countries are reacting too. Brazil, for instance, has set limits on how much steel can be imported from China. If more steel is imported than allowed, the extra steel will be taxed at a higher rate. Brazil is doing this to protect its local steel industry from being overwhelmed by cheap Chinese steel.

Source: Rhodium

This trend isn't confined to the steel industry. The U.S. and Europe have been imposing tariffs on Chinese goods, especially in sectors like electric vehicles, to shield their own industries from being flooded with cheap imports.

For example, in the U.S., President Biden recently announced a 100% tariff on electric vehicles, a 50% tariff on semiconductors, and a 25% tariff on EV batteries imported from China. Europe has followed suit, imposing extra temporary tariffs of up to 38% on electric vehicles imported from China.

This is a fascinating trend, and we’ll be diving deeper into it in the future.

Private sector is hot for India once again!

Most of us hear the term 'GDP' almost every day, but not many of us really know what it means. Simply put, GDP measures the amount of economic activity in a country. It's made up of a few key components:

1. What the country’s people spend.

2. What its government spends.

3. What people from abroad spend in the country.

4. And finally, investments.

A big part of this GDP calculation is investment. Investments are crucial because they act as a leading indicator of the economy. Essentially, the higher the investment, the more growth we can expect in the future.

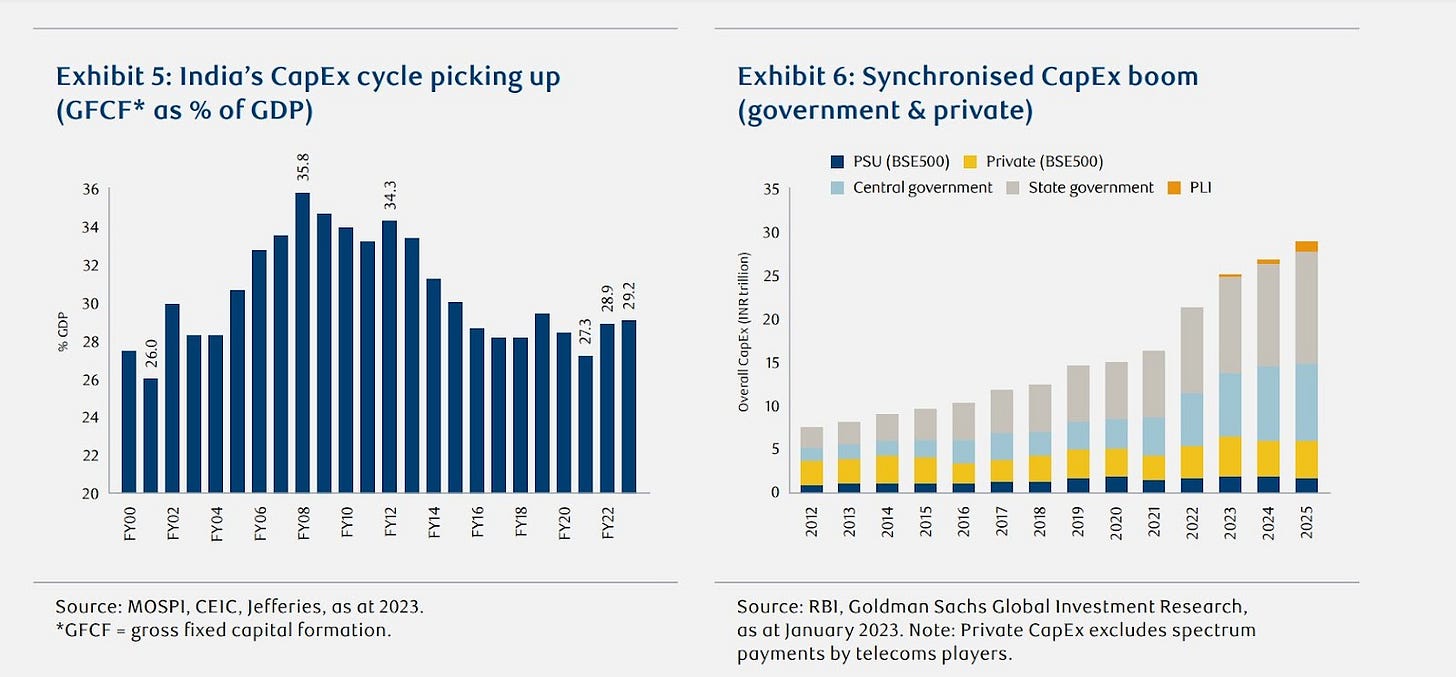

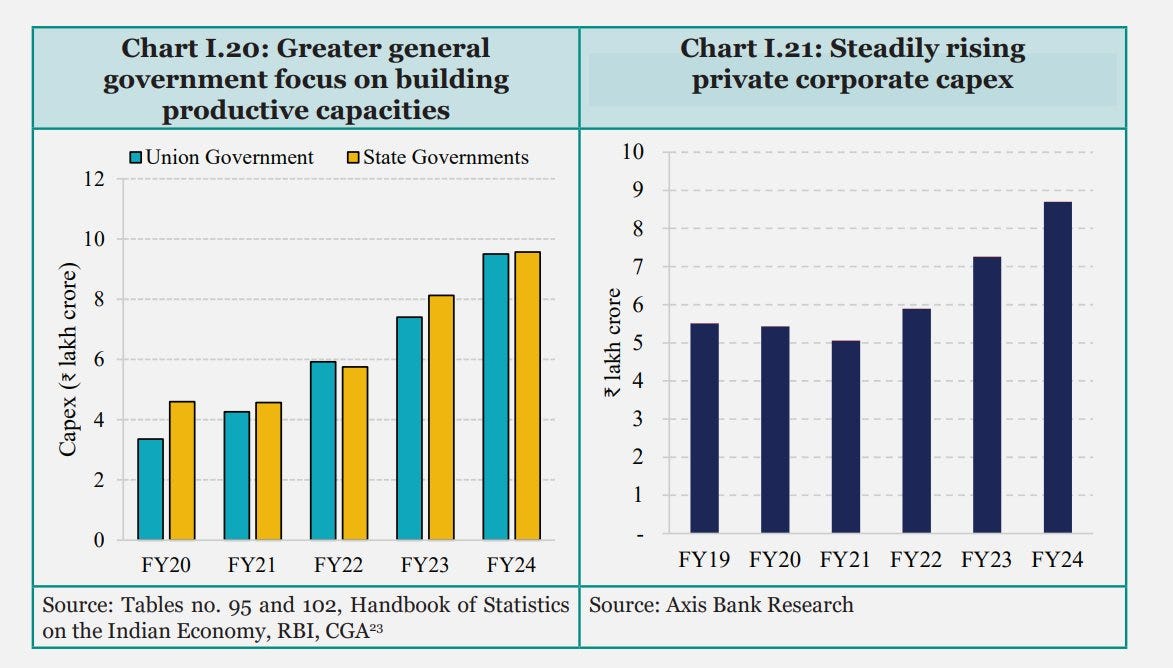

Now, these investments can come from either the private sector or the government. One thing the current NDA government has done well is ramping up infrastructure-related investments across the country. In fact, over the past few years, government capital expenditure (capex) has been a major driver of our economic growth, while private investments have barely budged.

But there's an interesting shift happening. Even though government investments are increasing, there's some reallocation going on. If we break it down, while direct investments by the government are on the rise, Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) or public sector companies are cutting back on their capital expenditure—the money they spend on expanding capacity, building new plants, etc.

According to a report by Motilal Oswal, PSU investments have dropped from about 2.3% of the country’s GDP in FY2020 to just 1.2% in FY2023. To put it in perspective, PSU capex was only 40% of the central government's capex in FY24, whereas about 10 years ago, it was almost 150%.

Source: Motilal Oswal

This suggests that a lot of government investment is now being made directly, instead of being funneled through PSUs. This could be intentional, possibly because PSUs are largely inefficient, or maybe there’s another reason—we can’t be entirely sure.

In an ideal scenario, government infrastructure investments should be followed by private investments. Think about it: if the government builds a road from point A to point B, it’s only truly beneficial for the economy if people on the A side can start trading more easily with people on the B side. So, you’d expect that after the government’s investment, a lot of private investment would follow to facilitate this trade. But strangely, since 2011, that hasn't been happening.

Until 2011, private investments in India were quite strong and consistently rising. They grew from around 10% of GDP in the 1980s to around 27% in 2007-08. But after 2011-12, they started dropping almost in a straight line. By 2020-21, private investments had fallen to just 19.6% of GDP.

Source: USMutual funds

Some economists suggest that this drop in investments could be due to low private consumption expenditures in India. But there might be another reason at play. In one of our older episodes, we referred to an editorial by economists Josh Felman and Arvind Subramanian. To give you a quick summary, they argued that while investing in India can yield great returns, it also comes with unique risks.

They pointed out that in India, there’s always a chance that your investment could suddenly lose value because government policies might shift against you. Even worse, this risk isn’t just for the future; it could also apply retrospectively! Something similar happened with Vodafone and a few other companies in 2011, and that very possibility might be scaring private investors away from putting their money into India.

But there’s some good news. According to a recent report from the RBI, private investments in the country seem to be picking up again. In FY23-24, private companies managed to raise ₹5.6 lakh crores from banks, IPOs, and external borrowings for 1,505 projects, compared to ₹3.5 lakh crores in FY22-23 for 982 projects. That’s pretty encouraging, especially considering how much people have been lamenting the lack of private investment.

Now, it’s important to note that not all of this ₹5.6 lakh crores will be spent in the same financial year. These investments typically happen in phases over multiple years. Of this total amount, the expected capex for this financial year is set to increase significantly from ₹1.59 lakh crores in 2023-24 to ₹2.45 lakh crores in 2024-25.

But remember, these are just investment intentions, not final investments. That means some of these investments might not materialize. There’s also the fact that project estimates can be revised up or down, or there could be significant delays—this is India, after all.

Still, investment intentions are an important early indicator. They give us a directional sense of whether the private sector is even thinking about investing. So, fingers crossed.

Source: Economic Survey

The past, present and future of the Indian economy

He pointed out that the recent increase in the investment rate has been driven by government expenditure, which has also led to a rise in fiscal deficits. However, he stressed that government investment alone is not the answer. Instead, the government must create an environment that encourages the private sector to invest heavily and become the dominant source of investment.

2. On the broader topic of development, Dr. Rangarajan emphasized the need for a multi-dimensional strategy. He explained that the Asian Tiger economies—Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and South Korea—had adopted a one-dimensional growth model focused solely on export-led growth. But, he noted that this model is no longer viable in today’s world, as advanced economies are not growing as rapidly as they were in the 1960s. Moreover, these same advanced economies, including the U.S. and Europe, which had championed free trade for over half a century, are now ironically becoming more protectionist. This means an export-first strategy won't work for India.

3. Perhaps the most significant point he made, in our view, was about India’s monumental challenge with employment. He highlighted that employment in India isn't growing as fast as income. While "jobless growth" is a concern, he also warned that jobs without growth are not sustainable. He further added that new technologies will only exacerbate the problem and that government jobs are not the solution.

Dr. Rangarajan's insights offer a sobering yet insightful perspective on India's economic journey and the road ahead. These are crucial issues that we'll need to consider as we continue to chart our path towards becoming a developed nation.

Watch the full interview here:

Is India open for business?

India's at a critical juncture right now. If we want to achieve our full potential, we've got a lot to do. We need to build and manage world-class businesses, embrace cutting-edge technology, and produce products and services that can compete in the best markets globally. And, perhaps most importantly, we need a significant amount of investment to fuel this growth. When you look at today’s advanced Western countries, it took them over two centuries to get where they are. But in the last fifty years or so, there's been a shortcut.

That shortcut is foreign investment. Foreign investors bring in the necessary funds to build factories, set up logistics networks, and invest in research and development—essentially everything India needs for its development. But they also bring in invaluable knowledge, teaching Indians the best ways to do business, drawn from their global experiences. Many of Asia’s most successful economies, like South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore, owe a lot of their spectacular growth to massive foreign investments.

India’s been trying to follow this playbook, but the journey has been anything but straightforward.

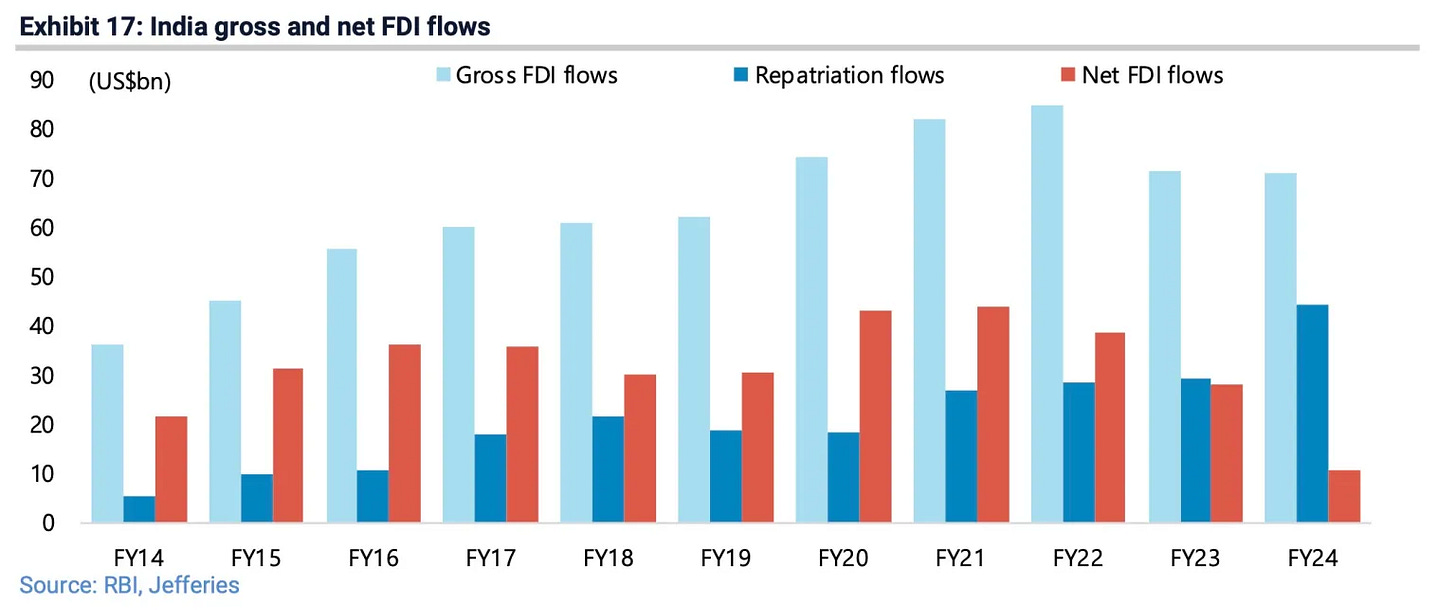

Before the Global Financial Crisis, India was seeing a sharp and steady increase in foreign investment. But after 2009, this trend reversed. FDI as a share of the Indian economy has never quite recovered to those pre-crisis levels.

While foreign investment hasn’t kept up with India’s growing economy, in absolute terms, investment into India was still on the rise. Gross investment inflows hit a high of US$ 84.8 billion in FY 2022. But then things took a turn. Last year, direct investment into India dropped to US$ 26.6 billion—the lowest we’ve seen since FY 2007. This happened for two main reasons. First, the money coming into India fell significantly, to US$ 71 billion. Second, investors pulled out a massive US$ 44.4 billion from the country—almost twice as much as they ever had before.

There are several reasons for this decline. For one, the global economy has shifted. Globalization is retreating in many parts of the world, and there have been serious economic headwinds in recent years. But that doesn’t explain everything. While global FDI fell by just 2% in 2023, investment into India plummeted by 43% over the same period. In 2022, India was the 8th most attractive destination for investment worldwide. By 2023, we’d dropped to 15th place, with our share of global investment shrinking significantly over the past couple of years.

Source: The Print

Here’s the challenge India faces: we can’t force foreign investors to do anything. They don’t live here, and we aren’t entitled to their money. The only way to attract them is to make India a great place to do business. It’s not enough to just showcase how large our market is. Investors need to believe that India’s regulatory policies will allow them to operate stably and flourish, without the government creating unnecessary obstacles.

Unfortunately, the Indian government has a reputation for making things difficult for businesses. Despite the economic liberalization we saw a few decades ago, businesses still have to navigate miles of red tape to get anything done. Just in the last couple of months, tax officials have gone after numerous companies for trivial issues, like sister companies in a conglomerate using the same name. India also hasn’t been too keen on investment treaties that protect foreign investors. In 2016, we canceled 76 out of 83 bilateral investment treaties.

But there’s some good news. So far, in FY 24–25, things have been looking up compared to FY 23–24. In the June quarter of this year, gross investment inflows into India were at US$ 22.5 billion, up from US$ 17.8 billion in the same quarter last year. Net FDI as a whole jumped from US$ 4.7 billion to US$ 6.9 billion. However, it’s worth noting that in June 2024 alone, investors withdrew US$ 6.7 billion from Indian markets—the highest amount ever recorded in a single month.

So, are we finally heading toward more investment, or are we scaring investors away? It’s tough to say for sure, but one thing’s clear: we need a lot more investment than we’re currently getting.

Will Zomato pull another Blinkit?

Let's break down Zomato's latest move.

Zomato just made a big splash by acquiring Paytm’s entertainment and ticketing business for over ₹2,400 crores. And yes, this is an all-cash deal. But this isn't just some random purchase—it’s a calculated, strategic step that could bring benefits to both Zomato and Paytm in different ways.

For Paytm, offloading this part of their business allows them to focus more on what they do best—financial services. Plus, with regulatory pressures mounting, this influx of cash will help them keep their shareholders satisfied, at least for a while.

For Zomato, it’s not just about adding another business to their portfolio. They’ve already ventured into new markets like quick commerce with Blinkit. Now, by acquiring Paytm’s movie and event ticketing business, Zomato is positioning itself to become the go-to app for all kinds of “going-out” experiences, complementing their existing dining-out unit, which, while a smaller part of their revenue, is still profitable.

In their recent quarterly results, Zomato’s management talked about the potential they see in the “going-out” space. They highlighted that their dining-out business, which helps people discover restaurants, is already profitable, with a run-rate of over $500 million in annualized gross order value (GOV). But they’re not stopping there. They’re planning to expand into other areas like movie tickets, sports events, live performances, shopping, and even staycations.

To bring this vision to life, Zomato is planning to launch a separate app called District by Zomato, focusing solely on these going-out experiences. They’re borrowing a page from the Blinkit playbook—creating a separate brand and app while still leveraging the traffic they already have on the Zomato platform to keep customer acquisition costs low.

According to Motilal Oswal, the take rate for this new business could be around 12%, although it might vary depending on the offering. For instance, movie tickets might have lower commissions, while exclusive rights to major sports or live music events could command much higher fees.

So, will this move be another home run like Blinkit, or could it fizzle out like the Zomato Legends venture, where people could order iconic dishes from other cities? Only time will tell.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

If you have any feedback do let us know in the comments.

You are doing Extraordinary research on our Economy