Pedal to the metal for India’s auto ancillaries

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Pedal to the metal for India’s auto ancillaries

Is Shiprocket a platform or a broker?

Pedal to the metal for India’s auto ancillaries

Recently, we broke down the business model behind auto ancillaries. It is rife with hazards: from razor-thin margins, to tight delivery obligations, to years of capex before earning anything.

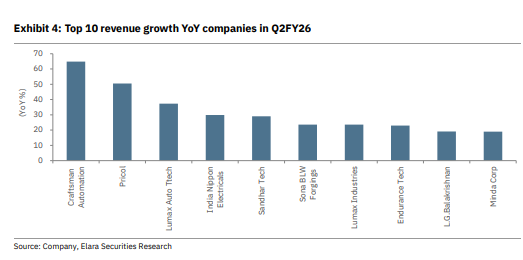

But, over the last few years, Indian auto ancillaries have been growing incredibly fast. Between FY22-23, the industry grew by a whopping 33% to ₹5.59 lakh crore — the fastest yearly growth ever. Since 2020, the industry has nearly doubled its revenue to ~₹6.7 lakh crore. In fact, in Q2 this year, two companies — Uno Minda and Sona Comstar — actually had their best quarter by revenue.

That kind of growth rarely happens without a structural cause. And right now, Indian auto ancillaries are going through multiple such changes, which are changing the landscape of the global auto industry. Those changes pose both opportunities and risks, and Indian suppliers are trying to position themselves in the best places possible to take advantage.

What’s driving this transformation? And what risks come bundled with the opportunity? Let’s dive into the major trends shaping this industry.

China +1

The first tailwind is one that we’re probably quite familiar with: the “China+1” strategy.

In the last 5 years, global trade has been completely ruptured by multiple factors. For one, there is an active US-China trade war, and secondly, the pandemic brought entire supply chains to a halt. Western automakers decided they’d had enough of putting all their eggs in the China basket, and began actively diversifying away from them. India emerged as a preferred alternative: cheaper labor, a large domestic auto market, and most importantly, an already-established ancillary ecosystem.

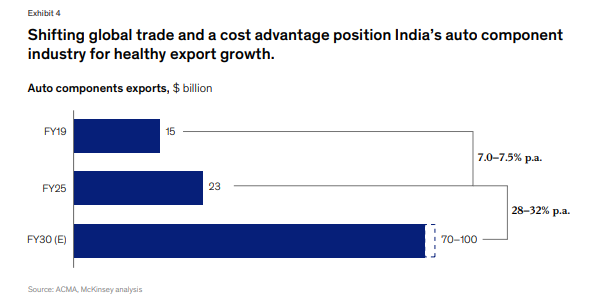

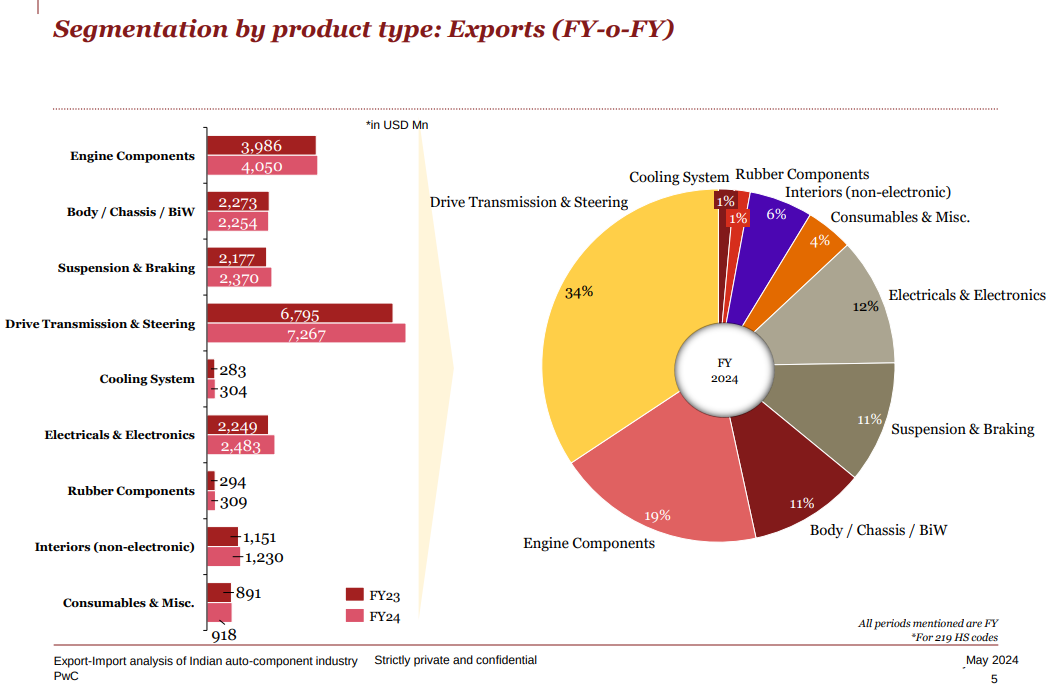

This shift has put India’s auto parts industry, which has always been domestic-heavy, into overdrive. Exports have risen significantly since the pandemic, reaching ~₹2.1 lakh crores now. The biggest source of demand comes from the US, but Europe and Asia also account for substantial shares. Because of this, India has flipped what has historically been a trade deficit in auto components into a trade surplus.

For a long time, this export boom was mostly driven not by breakthrough product innovations, but cost advantages in labor and other processes. India won orders because it’s cheaper and had dependable processes, not because it’s inventing new technologies.

However, that is also changing, and that’s where the second trend — of premiumization — comes in.

Premiumization

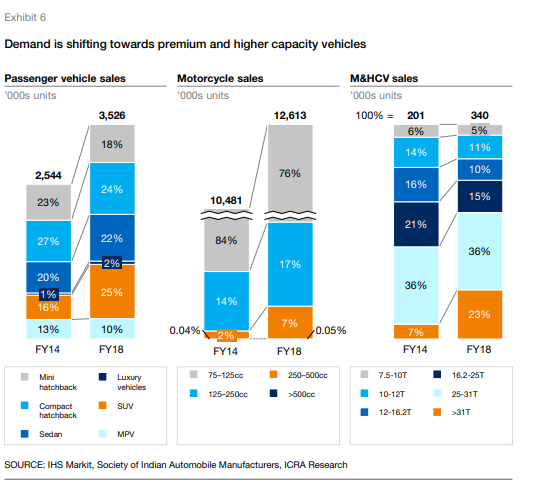

Indian consumers are no longer buying bare-bones utility vehicles. Increasingly, they want their cars to be rich with features, like advanced infotainment, ADAS sensors, upscale interiors, in-built dashcams, and so on. This wave of “premiumization“ is also transforming the suppliers of those components, where they’re looking to move up from selling just simple, commoditized goods to higher-value, potentially higher-margin goods.

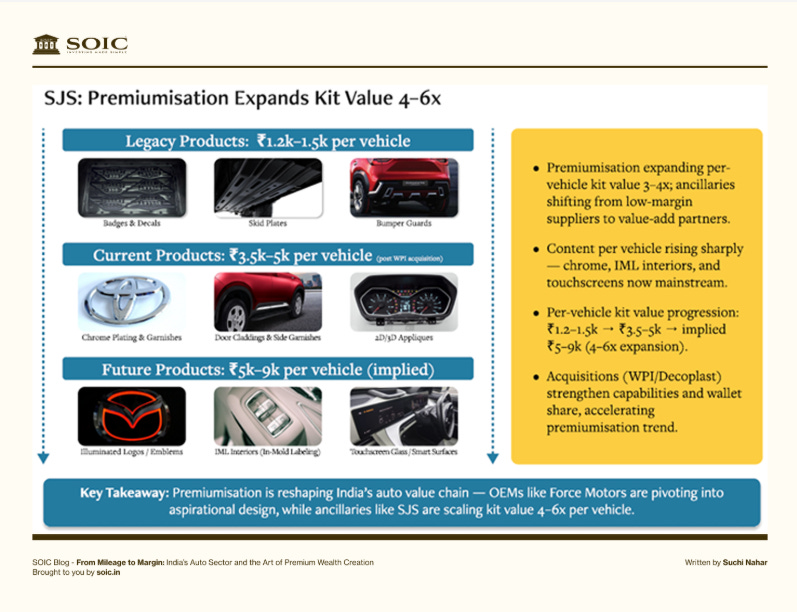

As we’d mentioned in our primer, auto ancillary is a sticky business — automakers don’t like to switch away from a supplier they’ve locked in. Suppliers have used that largely to their benefit. They may start with something as simple as decals and paints, but eventually move up to providing advanced interiors for the cars as well. This upselling and bundling has expanded kit values per vehicle by 3-4 times for certain categories of ancillaries.

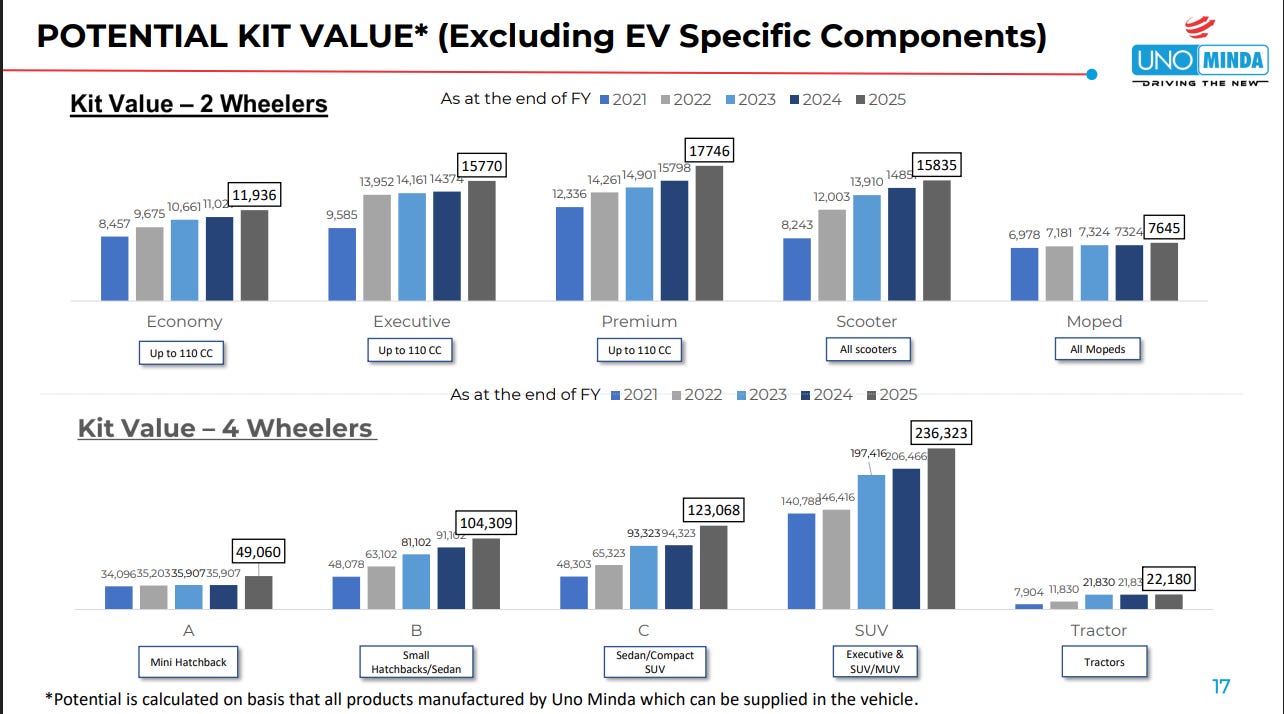

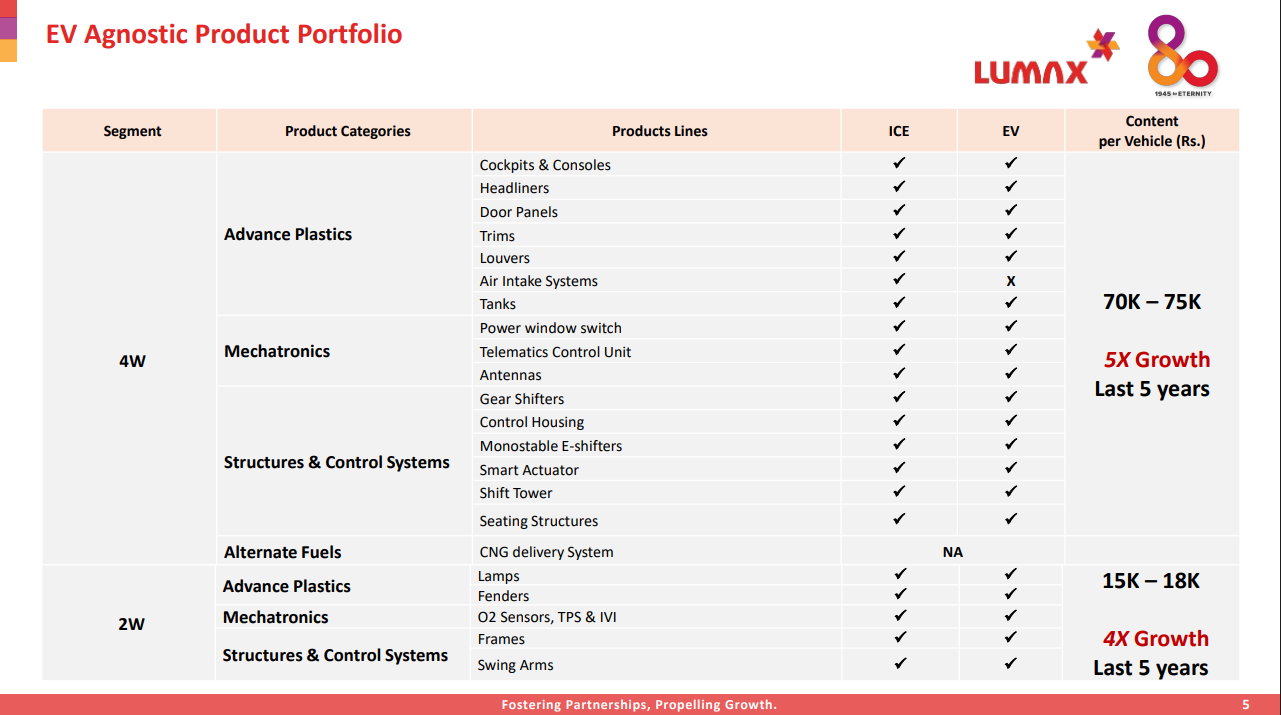

For instance, SJS Enterprises, for instance, has quadrupled its content per car from ₹1,200 to ₹3,500. Lumax Auto, meanwhile, went from being a mere plastic assembler to now designing whole cockpits for Mahindra. Uno Minda, meanwhile, has moved from simple ₹500 halogen bulbs to complex LED setups worth over ₹10,000.

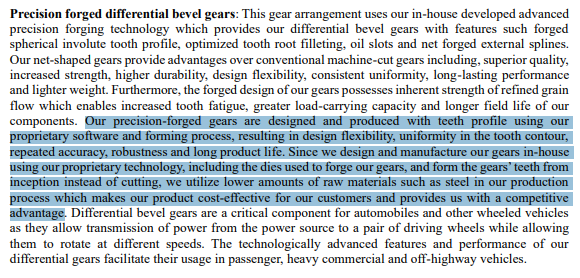

This isn’t just about selling more or better parts, though. It’s also about moving up the intellectual property ladder. Historically, Indian suppliers built as per the licensed designs of foreign firms. But now, many are developing their own designs. For instance, Sona Comstar owns key IP for gear design and software.

In some cases, if they don’t invent their own, they may even acquire them from elsewhere. For instance, Samvardhana Motherson, the largest Indian ancillary, acquired Germany-based Dr Schneider in 2023, adding over 200 patents related to high-end interior lighting.

Electric feel

Well, so far, so good for Indian auto ancillaries. But, much of this base has been built on the back of internal combustion engine (ICE) cars that use petrol and diesel. Almost all Western automakers also continue to be reliant on ICE cars. That brings us to what is perhaps the most important structural trend in the sector:

How do EVs change the game?

See, EVs need far fewer mechanical parts than internal combustion engines. No engines, no multi-gear transmissions, fewer moving components overall. Many Indian suppliers built their businesses around these products, which EVs now need much less of.

Instead, EVs use far more electronics than ICEs. A mainstream shift to EVs, especially in export markets, could hollow out the very product lines that made China+1 attractive.

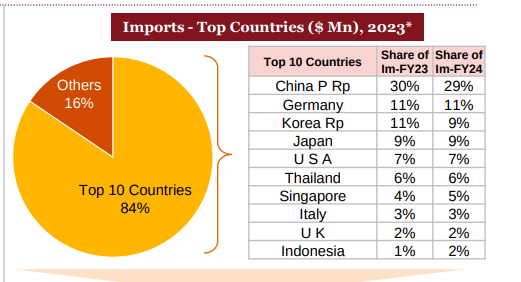

The threat goes beyond just obsolescence, though. Effectively, EVs bring back China to the centre of the global auto value chain. This creates the possibility of increased dependence on China. Except, where earlier the dependence was on auto parts, now it’s on fully-assembled cars. In fact, even with such a mature industry, India imports ~30% of our auto components from China.

But Indian ancillaries have hardly backed down from this challenge. In fact, they’re adapting with speed.

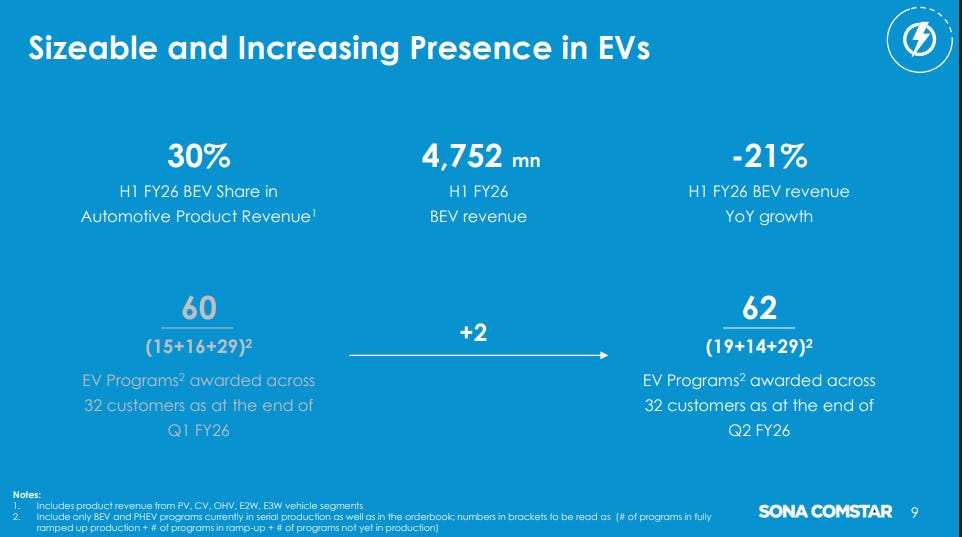

Take Sona Comstar, for instance. Originally a transmission gear and axle maker for ICE vehicles, it pivoted to driveline products specific for EVs, like e-axles, motor shafts and hub motors. It now derives ~30% of revenue from battery-EV vehicles and supplies EV makers globally. Sona even engineered a ferrite-based motor that avoids scarce rare-earth magnets — an important innovation considering China’s iron-hand grip on rare earths.

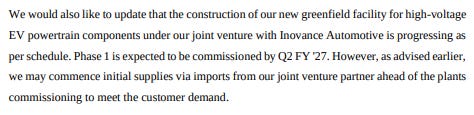

In fact, Indian suppliers have also been willing to work with Chinese suppliers themselves in different capacities to master EV components. Uno Minda, for instance, signed a joint venture deal with leading Chinese automation firm Inovance to make specialized EV parts. In fact, we’ve covered before how Indian battery firms like Exide and Amara Raja are working with Chinese firms to make their own.

The irony is striking: first, Western OEMs diversified away from China to India for ICE parts. Now, Indian suppliers are looking to work with — and even supply — to Chinese automakers. However, this doesn’t come without scrutiny. For instance, Sona Comstar’s partnership with Chinese firm Jinnaite Machinery has been held off due to “geopolitical factors”.

The return of vertical integration?

The EV disruption is also bringing back something that ICE cars had done away with — vertical integration.

In our primer, we covered how the auto industry increasingly fragmented, going from a single firm having end-to-end control of a car’s supply chain, to different firms existing for different auto parts. But EVs are reversing that trend. BYD, for instance, manufactures ~75% of its vehicle components internally, allowing them to manufacture for much cheaper. In contrast to ICEs, vertical integration in EVs is now yielding a huge cost advantage.

So, why does vertical integration work in EVs but not in ICEs? Well, EVs have fewer parts, so there’s much less to outsource. In fact, the most important component of an EV — the battery — alone accounts for ~40% the cost of an EV. So, if you control the battery and all that goes into it, you achieve a cost advantage.

Now, what this means for Indian auto ancillaries is unclear. What happens if Indian automakers, for instance, start excelling at making EVs? Will the economics then go against these ancillaries — even those who make EV components? This may not be necessary: even China has many players who supply EV components individually. But it is certainly worth thinking about.

A few Indian companies, in fact, might be experimenting on these lines. Take Tube Investments of India (TII), for instance, which makes chassis systems and steel tubes. Recently, it launched its own electric three-wheeler brand under TI Clean Mobility, with plans for electric trucks and even EV tractors. Additionally, it also acquired an electronics firm to ensure easy, captive supply for its EVs. This is a case of forward integration, where a component maker decides to make the vehicle itself, securing supply of the parts through itself for cheap.

Diversification

The last major trend is about hedging bets.

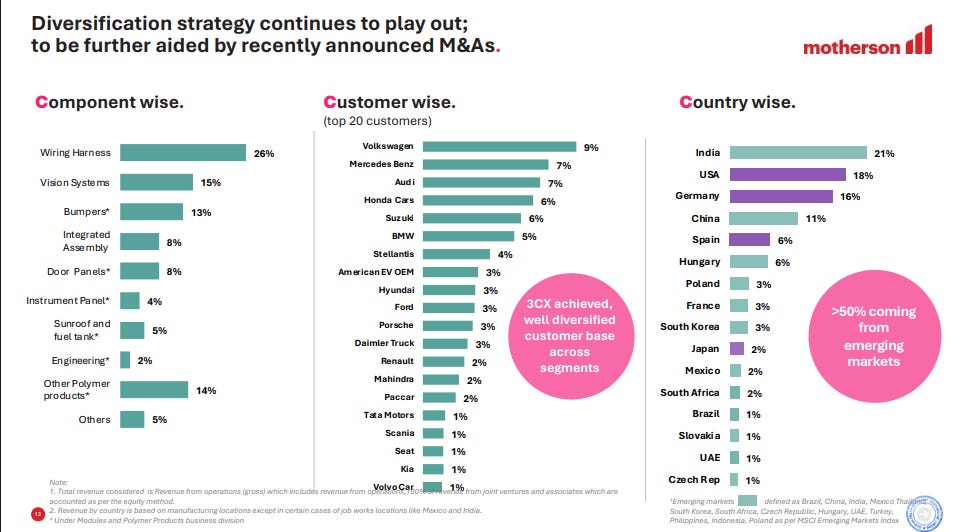

In our primer, we mentioned how auto ancillaries are attempting to diversify across automakers, geographies, and even industries — entering defence, healthcare, and so on. Given how sticky and unprofitable this business is, diversification becomes a method of building resilience. The largest players, like Motherson, understand this well, and that reflects in their business.

One could even say that hedging between EVs and ICEs right now is important, since neither technology has established full dominance yet. It may not be wise to try and secure the future by completely giving away a key strength right now.

Another important method of diversification is between passenger vehicles (PVs) and commercial vehicles (CVs). For one, PVs and CVs require different customizations in parts that otherwise serve a similar purpose. A truck that handles tons of cargo, for instance, will need a different family of similar parts than a family-oriented SUV.

Additionally, their business cycles work differently. If consumer demand slumps, PV sales fall. However, infrastructure spending might be up at the same time, keeping CV demand afloat.

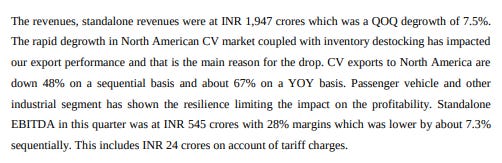

In fact, this quarter, that’s exactly what played out with Bharat Forge’s business. Exports to American CV makers fell, but that fall was made up by growth in the PV and industrial product lines.

Another hedge is within the PV space itself, between 2-wheelers and 4-wheelers. Usually, 2-wheelers are a proxy for the rural economy. So if growth there is fast while urban 4-wheelers stagnate, then a firm that has hedged well can benefit from that. In fact, Uno Minda’s business is evenly split between 2 and 4-wheelers.

Firm footing

India’s auto ancillary industry has transformed dramatically over the past decade. It’s no longer the low-cost, build-to-print supplier base of yesteryear. They are expanding globally, investing in R&D, developing EV-compatible products, and moving up the ladder.

But the risks they face are equally real. The same EV transition creating opportunities for some could hollow out legacy product lines for others. Meanwhile, import dependence on China for critical inputs continues to remain a vulnerability.

Who the winners of this market will be is still very undecided. But, as a whole, the Indian auto ancillary sector is finding a pretty solid footing in these rapidly-changing times.

Is Shiprocket a platform or a broker?

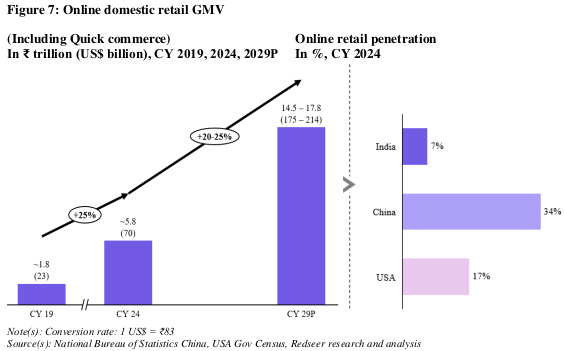

In today’s age of e-commerce and quick-commerce, it might not seem that way, but a surprising amount of Indian retail still happens offline. In China, for instance, 34% of retail activity happens through the internet. In India, we’re still at ~7%. It’s reasonable to believe that this number will grow.

Put yourselves in the shoes of an Indian retail MSME that wants to serve customers online, however. You essentially have two options. There’s the easy one — you plug into a platform like Amazon or Flipkart and benefit from their entire suite of services. That does, however, mean that you face brutal competition — often from the platforms themselves — and can bid goodbye to your data.

Then, there’s a harder answer. You take a series of tools — web portals, payments services, marketing and advertising tools, logistics, warehousing, and more — into a single stack. If you can marry them seamlessly, you’ve become a full-blown “D2C” player. But that’s not easy to do.

There’s room for a platform that just builds a “commerce enablement layer” — a platform that handles all these back-end problems for you. As a small business, you just plug your website or app in, and then focus on making things to sell.

That’s the dream behind Shiprocket. The company is gearing up for its initial public offering — an issue worth ₹2,342 crore. Of this, the company itself is raising ₹1,100 crore, while the rest will go to exiting shareholders. The company just filed an updated draft red herring prospectus, giving us a window into the company.

The pitch

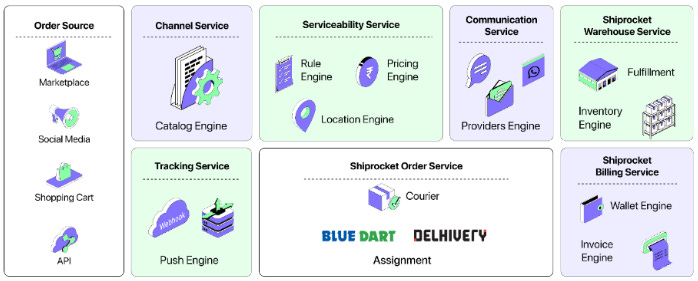

Shiprocket thinks of itself as an operating system layer for Indian businesses. It operates a platform that connects merchants to a network of third-party service providers — logistics and shipping firms, payments providers, warehousing companies, NBFCs, communication platforms and more.

Now, that isn’t how many of its customers see it. Many of its customers see it as, primarily, a logistics aggregator. To the company, however, that’s simply where the funnel begins.

The company’s big success lies in its ability to draw customers in at a low cost. Millions of visitors land on its site organically, every month, and a large number of them become customers without any intervention from the company itself. The company’s customer acquisition costs have been falling steadily over the years — from nearly ₹4,800 in FY 2023 to just over ₹2,800 in the first half of this year. In fact, 96.92% of the merchants it adds for its logistics business don’t even require the intervention of its support function.

The company’s pitch is that it can take this pool of customers, cross-sell all its other services to them, and eventually increase the revenue it earns per customer. According to the company, if a customer buys into their full suite of services, it could pocket as much as 20% of its customer’s sales.

That is, really, what makes it a platform. Otherwise, it’s simply a shipping middleman.

Two businesses in one?

How does this pitch actually hold up, however?

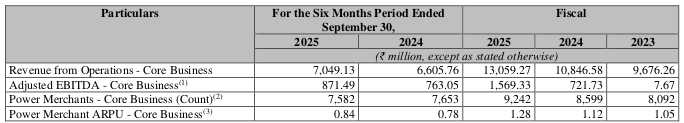

In practice, Shiprocket has two major revenue streams: its core business, which revolves around shipping; and its emerging businesses, which take many forms — from warehousing, to inventory management, to advertising and marketing, to credit. At least so far, the fates of these two businesses are entirely different.

Overall, the company is in a phase of rapid growth. In the two years between FY 2023 and FY 2025, its revenues grew at a CAGR of 22.43% — from just under ₹1,090 crore to over ₹1,630 crore. And with that, its unit economics is getting better as well.

Those revenues break neatly into two pools, however.

Four-fifths of its revenue — over ₹1,300 crore last year — comes from shipping. This is a reasonably mature business line. The company claims that it has been profitable since FY 2022 itself.

With time, it has also been able to scale without increasing costs proportionally. Analysts often measure the unit economics of a business through its contribution margin. For each Rupee a company earns, this tells you what’s left once you strip away the costs of actually providing that service. Shiprocket’s contribution margin, from this core business, has gone up from below 16% in FY 2023, to over 21% just two years later.

The rest of its revenue — under ₹330 crore in FY 2025 — came from its “emerging” business lines. These, however, have been bleeding money. Its EBITDA margin from these lines is a negative 45.97%. That is, for every rupee the company earns, it spends almost one and a half in operating costs alone.

Here’s a rather damning way of looking at it. In FY 2025, the company’s operating earnings from its core business — four-fifths of its business — were just under ₹157 crore. Meanwhile, it lost ₹150 crore in trying to provide those “emerging services” — just one-fifth of its business. In all, its “adjusted EBITDA” (which the company arrived at after knocking off some share-based payments it made) was barely over ₹7 crore.

In other words, all those “emerging” business lines drove its earnings down to practically nothing.

Why not stick to shipping?

Here, then, is the big question: why aim at becoming a platform at all? Why not operate as a simple logistics broker? Well, simply put, even with a digital skin, it’s hard to survive as a pure-play logistics middleman. It’s a business with a low ceiling, low margins, and missing moats.

Is an opportunity really there?

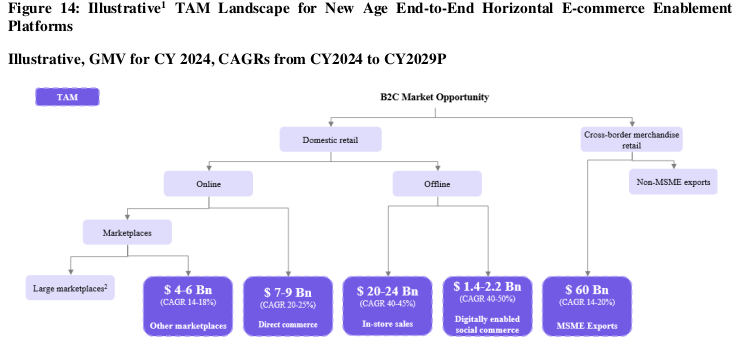

In theory, Shiprocket considers its total addressable market in the ballpark of ₹8 lakh crore. Naturally, with revenues under ₹2,000 crore, that is a distant dream.

At the moment, its shipping services — the heart of its enterprise — are growing at a CAGR of just over ~16%. That’s healthy, but it’s hardly the sign of an exploding business. If it were to stick to shipping, where would the next chapter of its growth come from?

There are untapped opportunities ahead of the company. Only, these aren’t easy to capture. The biggest, for instance, is helping small businesses ship their exports to other countries, which the company thinks could climb to ₹5 lakh crore. Recently, the company began tackling this market — in the first half of this financial year, it helped businesses ship over ₹300 crore across borders.

While there’s certainly a case to push this business ahead, though, it comes with serious frictions. It is a space where one has to deal with international regulations, customs, and more, all while trying to cut timelines. If you’re also expected to handle returns, it becomes doubly difficult. Perhaps Shiprocket can learn how to tackle them over time, but that isn’t guaranteed.

There are similar problems with many new segments the company is trying to tackle — from same-day hyperlocal deliveries to social commerce. It is not that these opportunities don’t exist. But they all require a whole new way of thinking about one’s operations from scratch. Whether the company can pull that off is an open question.

A tricky position

Meanwhile, even the company’s current position is hard to hold on to.

The company is, effectively, an aggregator for third-party logistics providers. It helps businesses connect with multiple logistics services, routes orders between them, and helps with communication and tracking. It does have some nifty features — from AI-enabled routing, to a system that plugs in well with the workflow of a business. But ultimately, the actual work of taking a package from point A to B is carried out by someone else.

Naturally, that’s where most of the money goes as well. The company’s “cost of merchant solutions” — delivery fees, communication costs, manpower etc. — eats up nearly three-fourths of its revenue. That is, for every ₹100 that comes to the company, almost ₹75 is instantly paid out to their partners. The remaining ₹25 is how they meet all their other costs, and their own earnings.

And if those partners try to negotiate higher rates, its margins could shrink even further.

This isn’t a distant fear. The company’s vendors include some of the largest in the business — from Bluedart, to Delhivery. These are large, powerful entities with genuine negotiating power. If they feel like Shiprocket’s take is too high, they could easily push back.

A squeeze in margins is one thing. But there are bigger challenges still. A large enough vendor could directly challenge Shiprocket, by building out a better dashboard and software interface for itself. This is already an industry with low switching costs — a business loses very little by moving to another logistics provider. If these vendors can undercut Shiprocket by enough of a margin, and offer a seamless enough user experience, those customers could easily leave.

This puts Shiprocket in a tricky spot. It must pay its vendors well, while keeping its own prices low. If either side thinks it’s eating away too much value, they could move away. This is why Shiprocket has to find ways of locking its customers into its platform. To them, the challenge is existential.

That stickiness is, arguably, what they’re trying to buy through all those bundled services.

Shiprocket needs a big win

Shiprocket is, at the moment, a loss-making business. It saw its first positive cash flows last year, but that’s still one setback away from a reversal.

It has a healthy business as a shipping aggregator, by all accounts, but not one that can justify a valuation that runs into tens of thousands of crores — at least not yet. Its longer play, of becoming an end-to-end e-commerce platform for small businesses, is not a guaranteed success. With massive amounts of investor capital and debt on its books, the company needs a way to get to success. Where that’ll come from, however, isn’t entirely clear to us.

The company has made mistakes before. In the last few years, for instance, it impaired its goodwill from the acquisition of start-ups like Pickrr and Swiftly — accounting speak for the fact that it perhaps paid more than it should have.

Don’t take this as investment advice. We’re just nerds who poured through an offer document — something you can do as well. But the way we see it, to prove its worth, Shiprocket needs a big win.

Tidbits:

Flipkart Clears Key Hurdle for India IPO

Flipkart received NCLT approval to shift its domicile from Singapore to India, moving closer to its planned 2026 IPO. The company, valued at $35–36 billion, now awaits government clearance under Press Note 3 rules.

Source: ET

NCDEX Gets SEBI Nod for Mutual Fund Platform

NCDEX received SEBI’s in-principle approval to launch a mutual fund transaction platform, aimed at enabling micro-SIPs in rural areas and serving as a precursor to its planned equity segment.

Source: ET

US Pauses $40 Billion Tech Deal with Britain

The US has paused a $40 billion technology agreement with Britain covering AI, quantum computing, and nuclear energy, citing frustration over UK digital regulations, digital services tax, and food safety rules.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Pranav.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

I think you meant to link https://thedailybrief.zerodha.com/i/181411419/a-primer-on-the-auto-ancillary-business in the first section