In the first two parts of this 2026 outlook series, the big takeaway was simple: the storm never really arrived. Inflation has cooled, interest rates have stopped rising, and the global economy has held up far better than most people expected. The widely feared recession, energy shock, or financial accident just didn’t happen.

But that doesn’t mean nothing is changing.

It means the changes are happening quietly—and often in places that don’t show up immediately in the headline numbers.

One of the biggest shifts is where the money is going. AI is no longer just a software story or an internet services theme. It’s starting to show up in the real economy—through spending on data centres, power infrastructure, semiconductors, and industrial capacity. On the surface, this looks like a normal capex cycle. But underneath, a lot of this spending is structural, not cyclical.

At the same time, global trade is being reshaped in slow motion. Supply chains are becoming more regional and more political. Cost and efficiency still matter, but they’re no longer the only priorities.

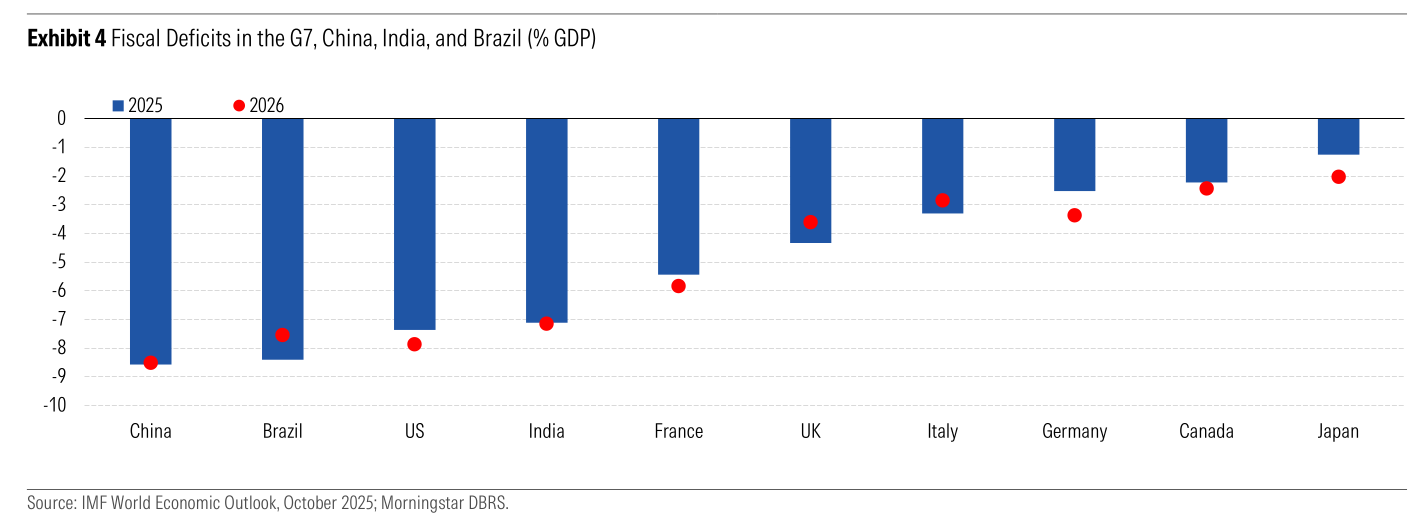

There’s also a quieter but important change in government finances. In many large economies, budget deficits no longer look temporary. They’re sticking around even when growth is decent, and employment is strong. That’s starting to influence how bond markets behave—and it limits how much room central banks really have to maneuver.

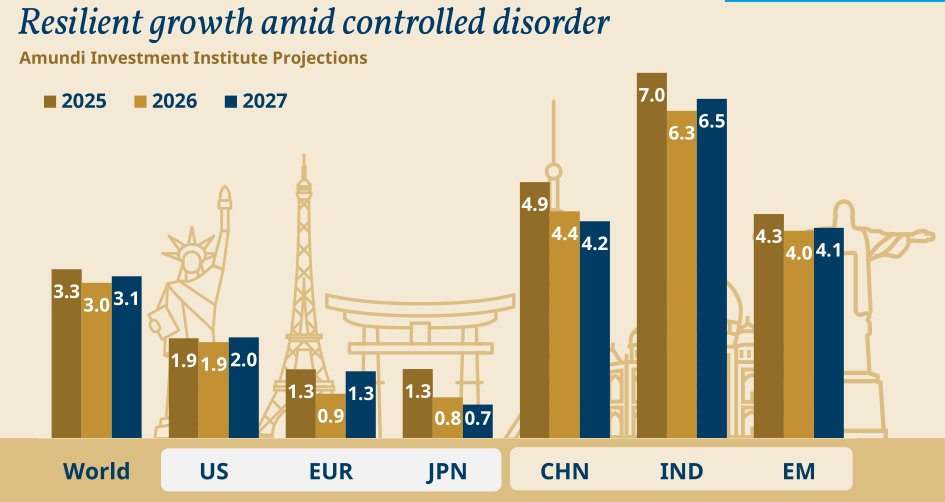

India’s 2026 outlook fits neatly into this global backdrop. On the surface, things look fairly comfortable. Growth is still stronger than in most large economies. Inflation has eased. And policymakers aren’t under the same pressure as their counterparts in the US or Europe.

But India is now entering a phase where growth can’t lean on one big engine anymore. It depends on several things going right at the same time.

Consumption has to gradually take the lead from investment. Government finances need to stay steady even if growth softens. The rupee is doing more of the work in absorbing global shocks. And markets are still figuring out how to value India in a world where global capital is far more selective than it was a few years ago.

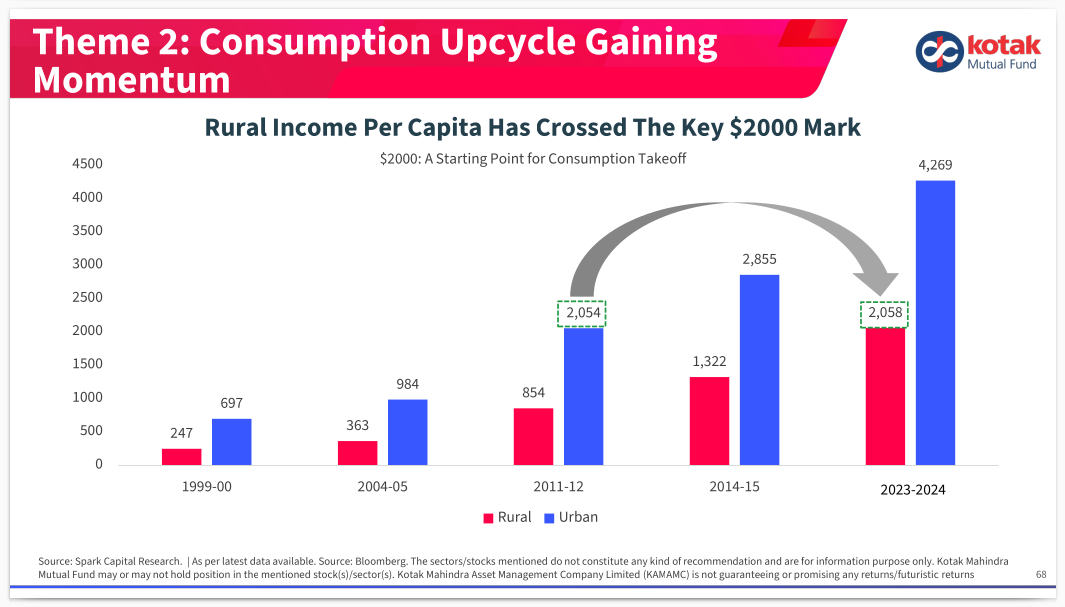

Most global outlooks agree on one point: India’s cyclical growth momentum is still intact. But they also highlight a transition underway—from investment-led growth to consumption-led growth.

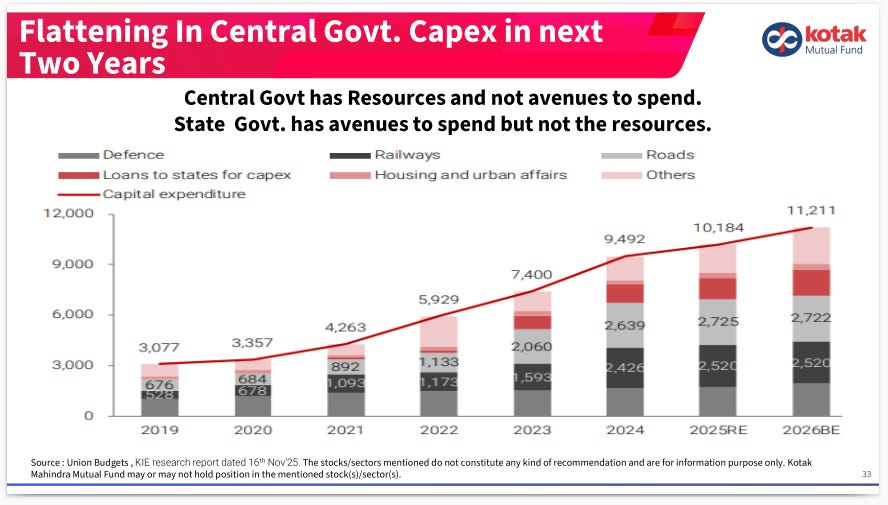

The post-pandemic recovery leaned heavily on public capex, infrastructure spending, and a strong investment cycle. That engine did what it was supposed to do. The next phase, though, depends much more on households.

Investment-led growth is usually clean and predictable on paper. Projects get announced, money is allocated, and execution can be tracked. Consumption-led growth is messier. It depends on how confident people feel, whether jobs are holding up, and how much room households have in their budgets when inflation or interest rates move.

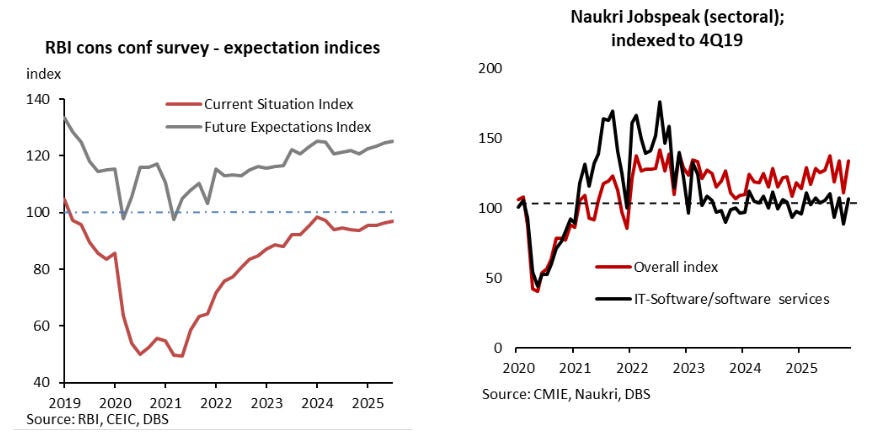

Let’s start with consumer confidence.

Households aren’t saying things feel great right now. Measures of the current situation have only just climbed back to around pre-pandemic levels. Expectations, though, tell a better story. People feel more optimistic about the year ahead, and that improvement has been steady through 2024 and 2025.

That gap between “now” and “next year” matters. It points to caution in the present but a willingness to spend if conditions don’t deteriorate.

Hiring shows a similar pattern. Employment is better than it was before the pandemic, but it isn’t broad-based. Banks, financial services, and parts of domestic services are adding jobs. IT and software are not. The result is enough income support to keep consumption steady—but not enough momentum to drive a sharp acceleration.

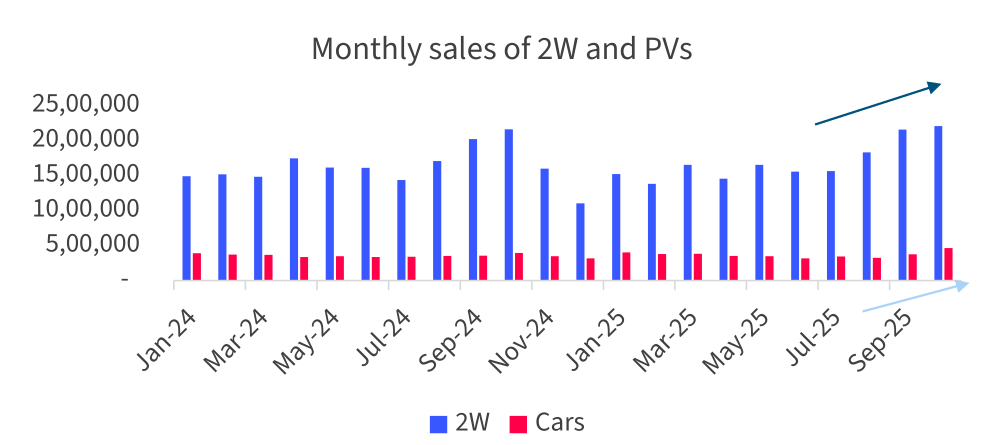

Spending data tells the same story. Vehicle registrations have held up through 2024 and into 2025, with occasional boosts from festive demand and GST cuts. These are exactly the kinds of purchases households postpone when confidence weakens. The fact that they haven’t dropped off tells us something important: people are cautious but not under stress.

At the same time, it raises a question. How durable is this demand once temporary supports fade?

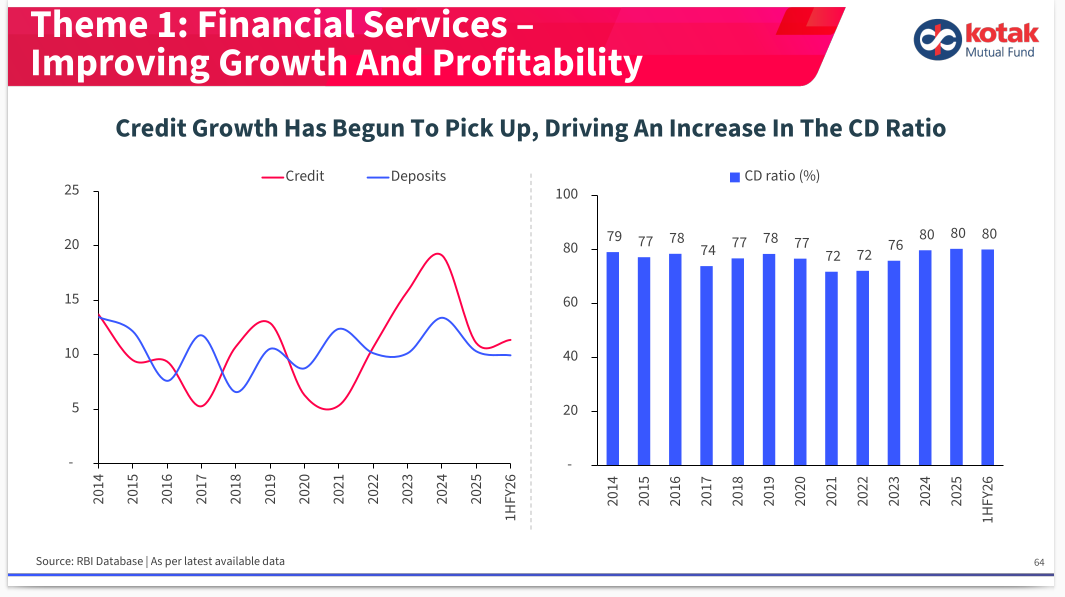

Credit growth to households has slowed from the peaks of 2023, but leverage is still higher than before the pandemic. Retail lending—especially unsecured credit—expanded rapidly in the post-pandemic recovery. Banks have started tightening at the margins, but the system is still digesting that expansion.

This doesn’t point to immediate stress. But it does put a ceiling on how fast consumption can pick up. When households are already carrying more debt, spending responds more to income stability than to lower interest rates alone.

All of this reinforces the broader theme. Consumption in 2026 is likely to be resilient, not explosive. It can keep growth steady, but it’s unlikely to deliver a sharp upside surprise unless income growth becomes much broader.

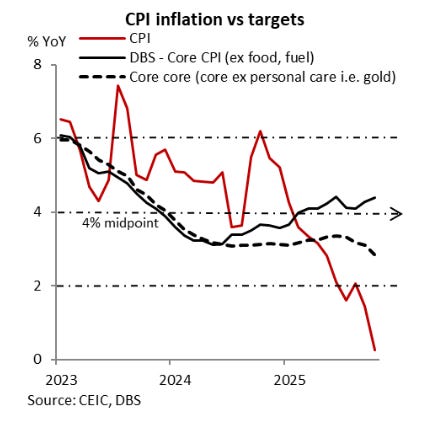

Inflation plays a big role in all of this.

Prices today are far lower than they were in 2022, especially food prices. That has eased pressure on household budgets. Even without strong wage growth, lower inflation has helped stabilize real purchasing power. In that sense, disinflation has quietly done a lot of the heavy lifting for consumption.

But there’s another side to this. Food is also the most volatile part of inflation. When prices are calm, it brings comfort—but it also brings fragility. A bad monsoon, a supply disruption, or a commodity shock that feeds through the currency can change the picture quickly. India’s inflation backdrop is supportive, but it isn’t bulletproof.

This matters for how we read growth numbers.

Several outlooks point out that real GDP growth in the first half of FY26 benefited from very low price growth in the economy. When prices barely rise, real growth can look strong even if incomes and cash flows are growing more slowly. Some base effects and technical factors also helped flatter growth for a few quarters.

That doesn’t mean the growth story is wrong. It just means headline numbers may be overstating the momentum on the ground.

Put differently, growth is real—but some of it looks better on paper because inflation is unusually low. As inflation normalises, growth may appear to slow even if underlying activity stays steady. From here, nominal growth—the kind that shows up in corporate revenues and tax collections—starts to matter much more.

Now let’s move to monetary policy.

One idea that keeps coming up in global outlooks is fiscal dominance—the sense that central banks have less freedom because governments are borrowing heavily, and cutting deficits is politically hard. India isn’t in the same place as the US or Europe. But the trade-offs still exist.

The RBI has room mainly because inflation is low. That gives policymakers flexibility. But it also means every move carries consequences—for the rupee, for imported inflation, and for overall financial conditions. Rate cuts are possible, and they’re likely to be gradual. The real question isn’t whether there’s one cut or two. It’s how carefully the RBI navigates a world where currency moves matter more, and global risk-off phases transmit quickly through capital flows.

Which brings us to the rupee.

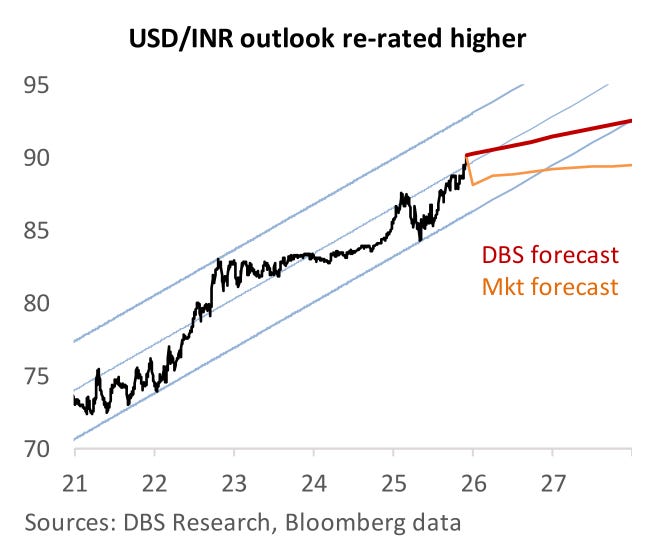

2025 wasn’t a great year for the currency, even as the dollar weakened globally. Looking ahead to 2026, most outlooks sketch two broad paths. In the base case, the rupee stays in the lower half of its long-term range and weakens gradually. In a more adverse scenario, it moves into the upper half of that range—implying sharper depreciation.

What separates these outcomes is largely external. Trade policy, tariffs, and global risk sentiment matter more now than they did earlier in the cycle. A stable trade environment helps anchor currency expectations. Sudden trade shocks do the opposite.

This is where trade stops being an abstract macro idea and starts showing up in everyday prices. Trade outcomes influence exports, capital flows, currency expectations, and inflation. For India, more of the adjustment is now happening through the rupee. The currency is increasingly being used as the shock absorber, rather than interest rates.

There’s also a more constructive side to the trade story.

As global supply chains fragment, India is slowly gaining share in manufacturing and export diversification. This doesn’t show up as a dramatic export surge. It shows up as steady gains across electronics, pharmaceuticals, engineering goods, and supply-chain relocation. It’s a slow, structural tailwind—not a cyclical boost—but it helps cushion growth when global demand is uneven.

These macro shifts are also playing out unevenly across sectors. Areas tied to domestic investment and balance-sheet strength—financials, infrastructure, manufacturing-linked industries, and parts of domestic services—look relatively better positioned going into 2026. Globally exposed sectors, especially IT services, continue to face headwinds from slower overseas demand and delayed client spending. Consumer-facing sectors sit somewhere in between, with staples supported by lower inflation and discretionary spending still sensitive to confidence and income trends.

On the fiscal side, India isn’t facing a loss of control. The bigger issue heading into 2026 is execution.

By the middle of FY26, central government revenues were running below budget assumptions. Gross tax collections were growing more slowly than needed to hit full-year targets. GST collections were also coming in below plan. Non-tax revenues and disinvestment receipts helped, but they didn’t fully close the gap.

That means more of the adjustment has to happen in the second half of the year.

If revenues don’t pick up meaningfully, the choices are limited. Either borrowing rises, or spending is adjusted by changing its timing or composition. Most outlooks assume the deficit target is broadly met. That implies spending flexibility does the heavy lifting, not a change in the headline number.

This is where India looks different from many advanced economies. In the US and parts of Europe, large deficits are being run even with steady growth and low unemployment. India’s fiscal stance is more disciplined. But that discipline also means fiscal space is being preserved, not expanded. If growth softens, there’s less room for discretionary stimulus, and more responsibility falls on private demand.

Now let’s turn to markets.

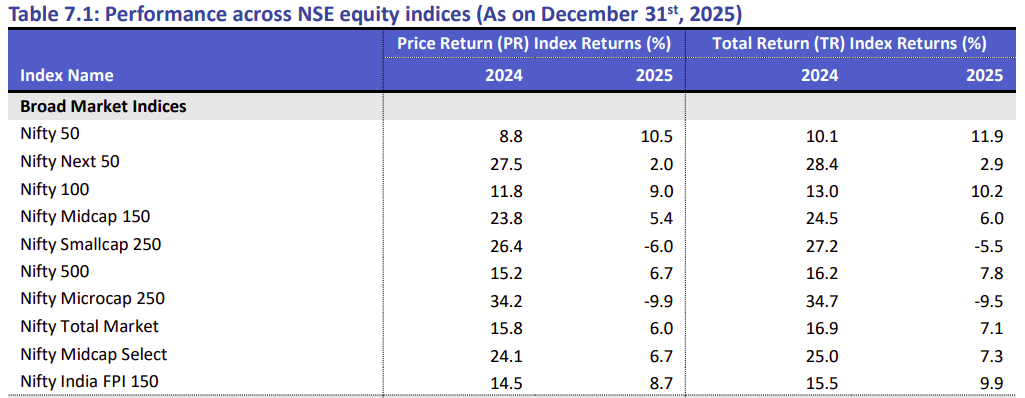

2025 wasn’t a bad year in headline terms, even if it didn’t feel that way. The Nifty 50 ended the year up a little over 10%. The pain was beneath the surface. Mid- and small-cap stocks underperformed sharply after delivering outsized gains in 2024.

Three factors explain why.

The first factor was earnings. At the start of 2025, earnings expectations for Indian companies were high, running in the mid-teens. As the year progressed, that optimism faded. Earnings upgrades slowed, forecasts were trimmed, and quarterly results stopped delivering upside surprises.

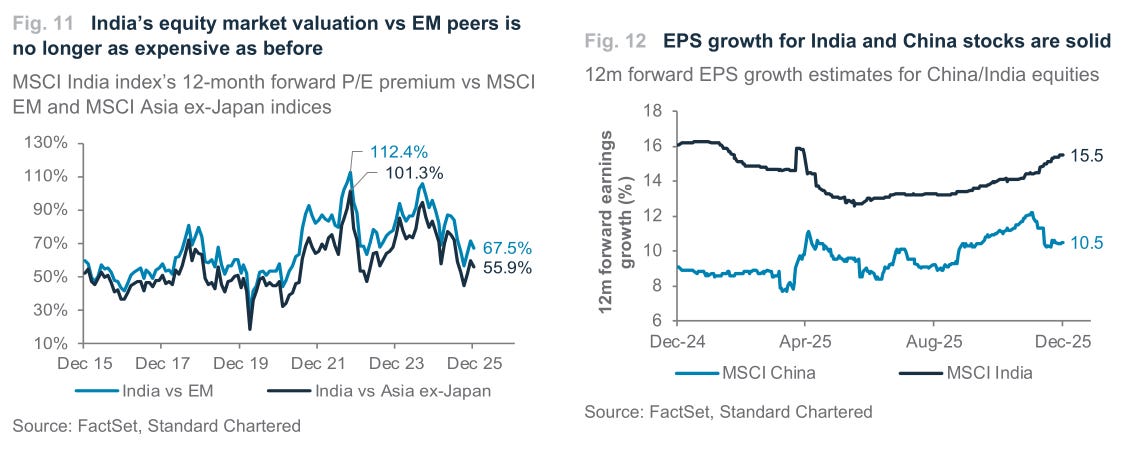

The second factor was valuations. Indian equities entered 2025 trading at a large premium to other emerging markets, with forward multiples well above the EM average. When starting valuations are that stretched, even modest earnings disappointment leads to underperformance. This effect was most visible in mid- and small-cap stocks, where valuations had expanded sharply during the 2024 rally.

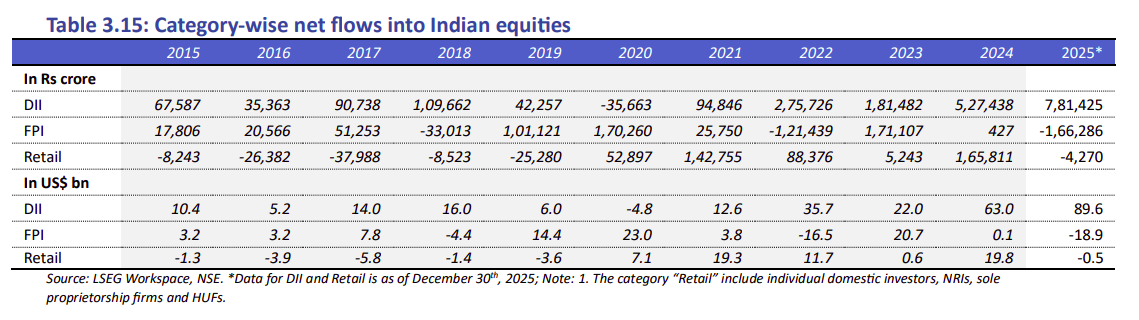

The third factor was foreign participation. Despite the correction in Indian markets since September 2024, foreign investors largely stayed on the sidelines instead of stepping in. There are two main reasons for this:

First, global conditions were not supportive. US interest rates stayed higher for longer through most of 2025, keeping dollar assets attractive and limiting risk appetite for emerging markets. In that environment, flows into EM equities remained selective rather than broad-based.

Second, valuations still mattered, as discussed earlier. Even after the correction, India continued to trade at a premium to most EM peers, which reduced the incentive for foreign investors to add exposure aggressively at a time when earnings momentum was slowing.

For 2026, the starting point looks different.

Valuations have reset more through time and underperformance than through sharp crashes. Expectations are lower. Foreign positioning is lighter. That changes how markets react to outcomes. Earnings don’t need to be exceptional to support returns. They just need to improve from 2025 levels and broaden beyond a narrow set of stocks.

At the same time, global equity returns are becoming increasingly concentrated in a small group of AI-linked US mega-caps. That concentration is forcing global investors to think harder about diversification.

The risks haven’t gone away. A global risk-off episode, a renewed spike in US yields, a currency shock, or another round of earnings disappointment would still weigh on flows.

But overall, things for 2026 are more balanced than they were a year ago. Growth is steady. Inflation is supportive. Policy has room, but not full freedom. And markets are far less euphoric.

After criticising others for giving outlook through various newsletters and saying they barely know anything about future to giving outlook for 2026 is absurd. Sorry if I am harsh I just want to point out you’re also part of circus